By Zachary Abuza

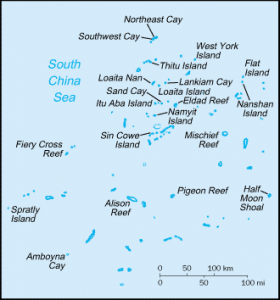

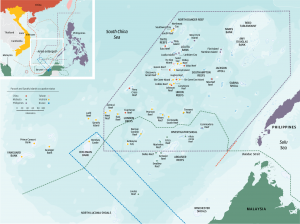

Since 2014, China has engaged in massive reclamation efforts in the Spratly islands, adding nearly 2,000 acres according to the U.S. Department of Defense. The placement, construction, and capabilities of these islands, including Johnson South, Cuateron, Gaven, Fiery Cross, Subi, Hughes, and Mischief Reefs has given China several strategic advantages and puts many Vietnamese held features in a vulnerable position. As a result of the reclamation approach, China can not only potentially control sea lines of communication and enforce an air defense identification zone (ADIZ), but challenge the status quo control of features in the Spratly Islands through anti-access area denial (A2/AD) operations.

While Chinese assertiveness and lack of transparency have driven Hanoi and Washington closer together, there remain limits to how far the relationship can grow as their strategic concerns and priorities do differ, despite US Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter’s 31 May – 2 June visit to Vietnam where he signed a Joint Vision Statement for Operations. While the United States is focused on freedom of navigation and overflight, Hanoi is primarily concerned about how the potential for China’s reclamation to challenge their Spratly holdings. Hanoi is right to be worried. China’s Military Strategy, released on 26 May 2015, makes clear that its patience for the “militarization” and “illegal occupation” of what it deems its territory is unlikely to be tolerated as it continues to make strategic investments in its maritime capabilities in the sovereign defense of its maritime domain.

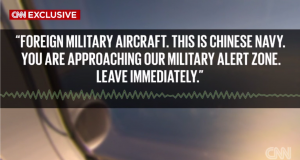

Chinese reclamation efforts and their ambiguous territorial claims threaten US interests in freedom of navigation. China has already said that “freedom of navigation definitely does not mean military vessel or aircraft of a foreign country can willfully enter the territorial waters or airspace.” On 25 May, the Foreign Ministry spokeswoman put it this way: “The freedom of navigation and over-flight, however, is not tantamount to the violation of the international law by foreign military vessels and aircraft in defiance of the legitimate rights and interests as well as the safety of over-flight and navigation of other countries.” China has warned that US challenge flights and ship passages, which to date have observed a 12NM distance from China’s reclaimed islands, are “irresponsible, dangerous” and risk provoking war.

The United States has signaled that it is going to increase its freedom of navigation and overflight challenges. On 27 May, US Secretary of Defense Ashton Carter warned Beijing: “There should be no mistake about this: The United States will fly, sail and operate wherever international law allows, as we do all around the world.” The establishment of territorial waters from artificial islands and the potential declaration of an ADIZ is an absolute redline for the United States.

But for Vietnam, the concern is less about freedom of navigation for the $5 trillion in international trade that passes through the South China Sea, and a more immediate concern about what Chinese reclamation efforts mean for the security of their held features.

Without naming Vietnam, China’s Military Strategy warns that “some of its offshore neighbors take provocative actions and reinforce their military presence on China’s reefs and islands that they have illegally occupied.” And in response to the international media’s focus on Chinese reclamation, their state-controlled media has highlighted Vietnamese efforts. As such, the 2015 white paper makes very clear that the China’s over-riding strategic interests are maritime in nature and that its force development will focus on “critical security domains,” maritime being the first.

China’s white paper singled out external countries that “Maintain constant close-in air and sea surveillance and reconnaissance against China,” i.e., the United States, it warned that “some of its offshore neighbors take provocative actions and reinforce their military presence on China’s reefs and islands that they have illegally occupied.” The focus on that “illegal occupation” will be driven by China’s new capabilities garnered through its reclamation efforts.

While China’s white paper reiterates Beijing’s long-held position that it only uses force defensively, Vietnam has an acute understanding of Chinese pre-emptive tactics. The white paper states a goal of “enrich[ing] the strategic concept of an active defense.” This translates into stealthy, proactive and pre-emptive tactics used to “defend” Chinese sovereignty. Their “active defense” strategy also talks about force “flexibility and mobility,” improved joint operations, “concentrat[ion] of superior forces, and the “integrated use of all operational means and methods.” The South China Sea is the proving ground for these new doctrines.

Vietnamese lawmakers are raising the concern that once China’s current reclamation efforts are completed, that it will have the military capabilities in place to renew offensive operations and grab other features, such as they did in March 1988 on Johnson Reef.

Yet that is unlikely for two reasons. First, the diplomatic fallout would be too great. A majority of the ever cautious ASEAN would be galvanized to act. There’s nothing that threatens China’s strategy more than a multilateral response and possibly even ASEAN moving forward with a Code of Conduct, without Chinese participation. Until now, as Patrick Cronin put it, China has successfully “relie[d] on this risk-averseness, and resort[ed] to divide-and-conquer tactics any time the 10 Southeast Asian countries appear to be uniting on anything, even a broad statement, that might be construed as antithetical to China’s interests.”

Second, Vietnam’s own military modernization has not gone unnoticed in China. Hanoi has seen the steadiest increase in military expenditure in the region: 314 percent between 2005 and 2014. In that time it has developed the most lethal power projection capabilities in Southeast Asia, including one of the largest navies, with three advanced Kilo-class submarines already delivered and the final three due in service by 2016, two Sigma class corvettes, two Gepard class frigates, with two more with ASW capabilities to be delivered this year, Molniya class corvettes now in indigenous production. Vietnam also has the most sophisticated missile force in the region, which now includes Yakhont and Shaddock anti ship missiles in indigenous production, Brahmos anti-ship missiles and Klub submarine launched missiles that could target Chinese facilities in the Spratlys. While Vietnam could not prevail in a a protracted conflict, it does have the capabilities to significantly raise the costs for China in a short-term exchange.

As such, China will continue to build islands, but by continuing to seize un-occupied and sub-surface features. It has no need to provoke armed conflict by attacking manned islands. Scarborough Shoal, seized in 2012 from the Philippines, should be seen as the template for future Chinese action. No country has China’s capacity for making islands out of nothing. Reclamation efforts will soon be complete and their fleet of dredgers will move on to the next strategic locales.

And it is this that gives Hanoi pause. More than armed conflict and the military seizure of some of the its 19 features with military personnel, is the fear of China becoming emboldened to begin engaging in A2/AD activities, harassing Vietnam from resupplying its small and indefensible concrete structures and some 16 lighthouses and aids to navigation, until diplomatic pressure against them builds and cooling off for a period of time before resuming those operations.

China is increasingly poised to engage in A2/AD operations against Vietnam in two locales, the Union and Thitu Reefs. The recent reports of self-propelled artillery being deployed on those reclaimed islands, as well as ramps in new structures to store such equipment, only adds to the mounting evidence that China is laying the groundwork for A2/AD operations, should it determine the conditions to be favorable.

For example, the two newly reclaimed islands of Johnson South and Hughes, are located in close proximity (eyesight) to four Vietnamese held features: Sin Cowe Island, Sin Cowe East Island, Collins Reef, and Landsdowne Reef. Sin Cowe is the seventh largest feature in the Spratlys, an eight hectare natural island, which the Vietnamese have built several all weather facilities, a lighthouse and done limited reclamation efforts. The latter two are simply concrete structures built on submerged reefs. While neither Johnson South or Hughes will have an airfield, both have helicopter pads and ports to enforce a maritime siege. Likewise, the newly created Gaven Island poises China to be able to deny access to Vietnam’s Sand Cay, a natural island, but also its small facilities on nearby Namyit, Eldad, and Petley Reefs.

Of even greater, though longer term, concern to Hanoi is the reclamation and construction on Cuateron Reef and Fiery Cross Reef, with its 3,000 meter airstrip, which will ultimately give China the ability to project power southwesterly into the Vietnamese-dominated London Reef region.

There needs to be serious thinking in both Hanoi and Washington about contingency planning should China try to enforce A2/AD policies. To date, China has used both grey hull and white hulled coast guard ships to try to block resupply efforts to the derelict Philippine ship Sierra Madre grounded on Second Thomas shoal, east of Mischief Reef. These newly reclaimed islands give them all the more capabilities for A2/AD operations. China will likely raise the costs for others for what it terms the “illegal occupation” of its national sovereignty. Routine and concerted harassment efforts may become a cornerstone of China’s strategy.

As Vietnam and the United States continue to deepen ties, including the current visit by Secretary of Defense Carter and the June 2015 visit to Washington by Communist Party General Secretary Nguyen Phu Trong, the two sides need to seriously discuss the strategic implications of China’s reclamation, and how they may be used to challenge the status quo. Aid for maritime security modernization, including $18 million for patrol craft are insufficient. And while the US and Vietnam have agreed to move forward with arms sales, there will always be limits to how much Hanoi is willing to and can afford to buy; though there are suggestions of some joint production. On 1 June, Secretary Carter and Vietnamese Defense Minister General Phung Quang Thanh signed their first “joint vision statement for greater operational cooperation.”

Make no mistake, Hanoi will never formally align itself with Washington against China. But it would be an important signal if this document addressed Chinese A2/AD operations, though unlikely as the bilateral defense relationship is still defined by the 2011 Memorandum of Understanding, which does not include kinetic operations.

And yet, the two sides need to have candid discussions regarding such scenarios. If China begins to engage in A2/AD activities how will the two sides respond, if at all? Could A2/AD operations against Vietnam pull in the United States? Should, for example, China try to prevent helicopter access to Vietnamese islands, would the US consider that the de facto imposition of an ADIZ? Is the harassment of Vietnamese resupply ships equivalent to trying to prevent international maritime shipping or freedom of navigation challenges by the US Navy?

Vietnam is clearly pleased with a more robust US presence in the South China Sea and its more assertive challenge to Chinese sovereignty claims. But efforts to date failed to deter China from reclamation. The next phase has to be developing a strategy that deters China from using the reclaimed islands to challenge the territorial status quo, freedom of navigation and overflight.

Zachary Abuza, PhD is an independent analyst of Southeast Asian politics and security affairs. Follow him on Twitter at @ZachAbuza.