This post originally appeared on Navy Grade 36 Bureaucrat. It can be found in its original form here.

At first glance, the recently released Asia-Pacific Maritime Security Strategy looks like a rehash of a lot of old points about the US’ position on Pacific matters. But upon closer examination, there is a key shift in language that those of us who watch the region will take note of. Here are ten things you might have missed:

1. It calls out the Senate directly on UNCLOS, but doesn’t address ISA.

Normally DoD publications don’t delve too much into policy matters with Congress. But it’s hard to say that about this statement:

“This is why the United States operates consistent with – even though the U.S. Senate has yet to provide its advice and consent – the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea”

UNCLOS was originally opposed due to the International Seabed Authority (ISA), which does such un-American things like taxing sea bed mining for distribution to other countries and mandating technology transfer. The military normally focuses on the navigation portion of UNCLOS, which it has abided by since the Regan era. The problem comes when the US is encouraging nations to use UNCLOS while not actually having ratified the treaty. There isn’t an easy solution, short of removing the ISA from UNCLOS, but expect to see UNCLOS ratification cries in the near future.

2. It calls out everyone on the South China Sea.

It’s not just China. Every claimant in the South China Seas has issues. This document clearly spells that out, taking away a talking point from the PRC that the US is overlooking the other countries to focus on China. But it pulls no punches on China, going after the “so-called Nine-Dash Line” as an excessive claim.

3. It spells out why the Senkakus became a problem.

Most people view the Senkakus as a bunch of rocks that China and Japan hold in dispute. Very few know that the Japanese government bought them in order to prevent the Governor of Tokyo from buying them. This was actually an attempt to prevent a clash with China, since the Governor was rightwing and would likely have stoked the issue. This narrative has been lost to China’s narrative about how Japan “changed the status quo,” so it’s good to see it spelled out here.

4. It puts India as a model for dispute resolution.

Comparing the India/Bangladesh maritime dispute resolution to what is occurring in the South China Sea is no accident. This document clearly spells out US support to India, likely in an attempt to spur continued Indian investment in their “Look East” strategy.

5. It denies territorial sea around reclaimed islands.

This is big.

“At least some of these features were not naturally formed areas of land that were above water at high tide and, thus, under international law as reflected in the Law of the Sea Convention, cannot generate any maritime zones (e.g., territorial seas or exclusive economic zones). Artificial islands built on such features could, at most, generate 500-meter safety zones, which must be established in conformity with requirements specified in the Law of the Sea Convention.”

This is a clear US denial of any Chinese territorial claim of these features. This has been implied before, but not ever strongly stated. On that same note…

6. Freedom of Navigation (FON) is coming to you.

One paragraph in particular tells us to expect more FON operations:

“Over the past two years, the Department has undertaken an effort to reinvigorate our Freedom of Navigation program, in concert with the Department of State, to ensure that we regularly and consistently challenge excessive maritime claims.”

Coming on the heels of stating that PRC reclaimed land is an excessive claim, this is a really good sign, although realize that future FON operations will likely include challenges to all claimants (and make diplomatic efforts interesting).

7. It accuses China of changing the status quo.

If you sit on a beach, you’ll watch the waves crash against rocks. The seawater slowly erodes the rocks until they split open at seams you couldn’t have seen before. This is analogous to China’s strategy in the East and South China Seas. They have slowly worn away at seams around every other claimant, always claiming to “maintain the status quo” when in reality they are waiting for the other claimant to make the first move, then instantly cry that they are the victim. Scarborough Reef is a classic example, yet the media has essentially ignored the issue. Luckily, this document calls it out, stating “China is unilaterally altering the physical status quo in the region.”

8. It calls out A2/AD and how we would stop any short war.

It gives vague language to DoD efforts to combat A2/AD, but it does say that it’s happening, with “robotics, autonomous systems, miniaturization, big data, and additive manufacturing.” It also later mentions that we’ll be dispersing around the Pacific, into more Japanese bases and places like Australia. This complicates PRC targeting. Will the PRC risk war with the US if we have units spread out everywhere? They don’t have enough missiles to hit everything, and striking into a country like Australia means that any sort of “short, sharp war” on their part quickly expands…something that will cause a lot of angst on their end.

9. It calls out information sharing with allies.

“This is why DoD is working closely with partners in the Asia-Pacific region to encourage greater information sharing and the establishment of a regional maritime domain awareness network that could provide a common operating picture and real-time dissemination of data.”

I’ve long argued that sharing data with allies is too hard. At the CJOS-COE we worked hard to make Carrier Strike Groups use networks that supported integrating ships from non-“Five Eyes” countries, like Germany and Norway. We proved that successfully, and in the Pacific we’ve integrated South Korean and Japanese ships before. But what about Malaysia? Indonesia? Brunei? We get some play at RIMPAC, but not enough. The disaster that was ABDA in World War 2 wasn’t that long ago. We need to get friendly nation integration right before any shooting starts.

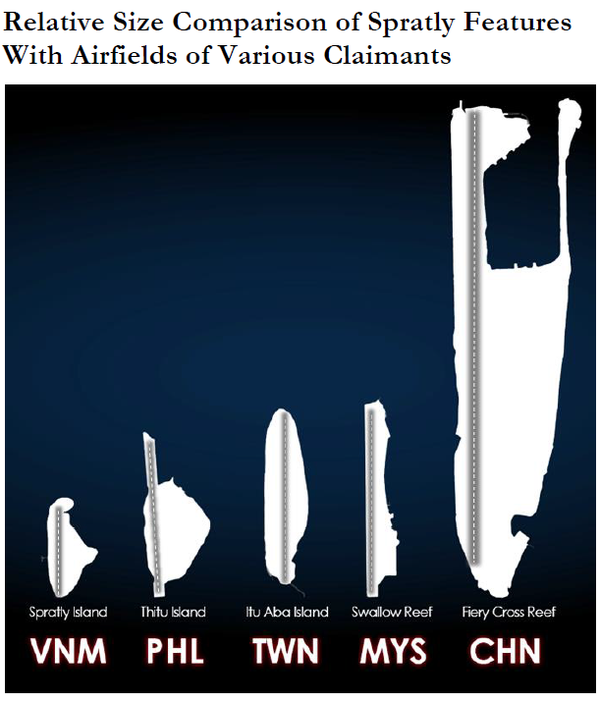

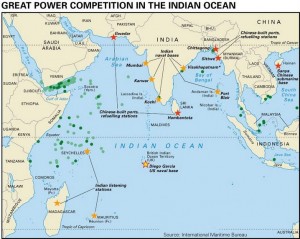

10. It’s got great graphics.

From the scale model of Fiery Cross Reef reclamation to a very nice and detailed map of South China Sea features, this is one of the few documents that uses more than just pretty pictures of military equipment. Well done to the authors who picked quality illustrations to help drive their points home…almost as good as my choice of memes 🙂

Ryan Haag is the Hawaii CIMSEC President and an Information Warfare Officer navigating the uncharted waters of the Information Dominance Corps. He can be reached through his blog at The Navy’s Grade 36 Bureaucrat.