This article was originally posted at the National Maritime Foundation. It is republished here with the author’s permission. Read the piece in its original form here.

By Gurpreet S. Khurana

In December 2015, China commissioned Hefei (174) – the third Type 052D guided-missile destroyer into its navy. The warship represents the most advanced surface combatant ever operated by the PLA Navy, comparable to the best in the world. It is armed with potent long-range missiles like the HHQ-9 (anti-air), the YJ-18 (anti-ship), and the CJ-10 (land-attack).[ii] This seems incredible considering that until barely a decade ago, China’s navy did not even possess a credible fleet air defence missile system, let alone a land-attack capability.

Notably, all three Type 052D destroyers are based in PLA Navy’s South Sea Fleet (SSF).[iii] This is among the latest indicators of the growing salience and strength of this fleet. The SSF is fast becoming the ‘sword arm’ of the PLA Navy. It is rapidly amassing distant power-projection capabilities with major geopolitical and security ramifications not only for the China’s immediate maritime neighbours in the South China Sea (SCS), but also for the littorals of the Indian Ocean region (IOR). This essay attempts to discern the trends since the rise of China’s naval power in recent decades, and the implications for the Indo-Pacific[iv] region.

Circa 1995-2005: Focus on ESF

Until the 1980s, the PLA Navy was merely a ‘brown-water’ coastal force. Beginning in the mid-1990s, China’s naval power witnessed a quantum jump with the acquisition of the Russian Kilo-class submarines and Sovremenny-class destroyers. The Kilos were considered to be the quietest submarines in the world, whereas the Sovremennys were armed with the lethal S-22 Moskit anti-ship missile – dubbed ‘aircraft-carrier killer’

– whose supersonic speed gives little reaction time to the victim warship to defend itself.

All four Sovremennys[v] and eight Kilos[vi] were added to the East Sea Fleet (ESF). At this time, China’s strategic focus was directed towards its eastern seaboard, primarily to prepare for any adverse contingency involving Taiwan (in light of the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait crisis). In 1999, China began the indigenous development of its Song-class conventional submarines. The first of these new-generation boats commissioned between 2001 and 2004 were also inducted into the ESF.[vii]

Circa 2005-2010: Focus on the South Sea Fleet

About a decade after the Taiwan Strait crisis, China’s strategic focus began to shift from Taiwan to its maritime-territorial claims in the South China Sea (SCS). The reason for the shift is unclear. It could be attributed to Beijing’s successful ‘Taiwan policy’ that led to a reduced probability of a military conflict across the Taiwan Strait. It is also possible that Beijing had always considered the SCS as its priority, but was ‘biding its time’ due to various geopolitical and capability constraints. All the same, China’s intent became apparent through the increasing ‘capabilities’ being allocated to the SSF, such as those enumerated below.

- 2004-05: SSF inducts two each of Type 052B and 052C destroyers, the first-ever world-class indigenous warship designs.[viii]

- 2005: China begins refurbishing the erstwhile Soviet aircraft carrier Varyag for power-projection in the SCS (that later joined SSF as Liaoning).

- 2006-07: SSF inducts four additional Kilo-class submarines procured from Russia.

- End-2007: SSF inducts the first Type 071 Yuzhao-class Landing Platform Dock (LPD), which provided China a distant sealift capability.[ix]

- Mid-2008: Satellite-based reports carried pictures of China’s new Yalong Bay base in southern Hainan, indicating entrances to the underground submarine pens and a Jin-class (Type 094) new-generation nuclear ballistic missile submarine (SSBN).

- 2007-08: Extension of Woody Island airstrip (Paracels) to 8,100 feet. The airstrip was now capable of operating heavier aircraft like bombers, transports and aerial-refuellers.[xi]

Most of these developments were analysed in 2008-2009 by this author and a few other analysts like James Bussert. However, these writings received little attention. Interestingly, China’s ‘intentions’ became clearer within a couple of years when Beijing declared in 2010 that the SCS was its “core interest” of sovereignty. Two years later, in 2012, China upgraded Sansha City on Woody Island from county-level to a prefecture-city level[xv] to facilitate the administration of all the island groups in SCS claimed by China. It also established a military command in Sansha City under Hainan provincial sub-command within the Guangzhou Military Command. While these were largely ‘administrative’ and ‘defensive’ policy measures, these reinforced China intent with regard to its “core interest” of sovereignty.

Recent Developments: Reinforced Focus on SSF

Recent developments clearly indicate that China has persevered with its southward-oriented military-strategic intent. The latest of these is China’s January 2016 redeployment of its Haiyang Shiyou 981 (HD-981) oil rig in disputed waters with Vietnam, which created a major diplomatic rift between the two countries in mid-2014. A CSIS report released in January 2016 notes an “accelerated…frequency of its (China’s) coercive activities and pace of its island-building in the… South China Sea.”[ The report adds that “the PLA in the near future will be operating well beyond the First Island Chain and into the Indian Ocean.” If such predictions are substantive, what precisely may be among the enabling capabilities?

Aircraft Carrier Task Force

In 2012, Varyag was commissioned as Liaoning, and soon after sea-trials, it was based in the SSF. China is building an indigenous carrier, which is also likely to be based in the SSF for patrols in the disputed South China Sea. These carriers have potent escort combatants. In addition to the Type 052D destroyers, most of the PLA Navy’s latest Jiangkai II class frigates are also based in the SSF. The carrier(s) – along with these escorts – would provide versatility to the SSF to conduct missions in the IOR and SCS across the spectrum of conflict, ranging from humanitarian missions and counter-piracy to flag-showing, and supporting maritime expeditionary operations to military coercion.

Notably, both Jiangkai II frigates – Liuzhou (573) and Sanya (574) – that participated in India’s International Fleet Review-2016 (IFR-16) at Visakhapatnam in early-February 2016 are based at SSF. The two ships – part of PLA Navy’s 21st anti-piracy task force – made a ‘goodwill’ port call at Chittagong and conducted combined naval exercises with the Bangladesh Navy, before participating in IFR-16. In the coming years, the availability of the carrier in its task force will provide the PLA Navy more operational options, enabling it to undertake other types of missions in the IOR as well.

‘Unsinkable’ Aircraft Carriers in the SCS

China is likely to continue upgrading its airfields in the Paracels and Spratlys. On Woody Island, satellite imagery revealed that since 2007-08, China has added a wide array of aviation infrastructure to the main airstrip, including aircraft hangers, air traffic control buildings and radars, fuel depots, crew accommodation, and berthing facilities for larger warships. This would provide a force-multiplier effect to the PLA Navy’s carrier operations, enabling China to effectively exercise sea control and power-projection in the SCS. It would also enable China to enforce an ADIZ over the SCS, if Beijing were to promulgate it.

New-Generation Submarines

In mid-2015, the PLA Navy commissioned three modified Shang-class SSNs (Type 093A/ 093G). Like Type 052D destroyers, these are likely to be armed with the vertical-launch YJ-18 anti-ship and CJ-10 land-attack missiles. In a few years, China is likely to develop the advanced Jin-class (Type 096) SSBN, which could provide China a more credible nuclear deterrence and first strike capability. Although Yalong Bay (Hainan) may be home base for these nuclear-propelled platforms, their virtually unlimited endurance will enable the PLA Navy to project submarine-based maritime power eastwards far beyond the second island chain, and westwards into the IOR.

China’s latest conventional submarines, the Song-class and the Yuan-class with Air Independent Propulsion (AIP), are also based at Yalong Bay.[xxiv] Notably, all submarines that the PLA Navy has deployed so far in the IOR are based in the SSF. These include the Song-329 that docked in Colombo in September-October 2014[xxv] and the Yuan 335 that spent a week in Karachi harbour in May 2015.

Expeditionary Forces

In 2011-12, two more Type 071 LPDs (Jinggang Shan and Changbai Shan) joined the first LPD (Kunlun Shan) in the SSF. In mid-2015, the SSF inducted the PLA Navy’s first Landing Platform (MLP). Based on the novel submersible roll-on/ roll-off (RO-RO) design developed by the United States, MLPs would be able to transport PLA Navy’s heavy Zubr-class air-cushion landing craft to distant littorals.

This enhanced distant sealift capacity would not only enable the SSF to undertake humanitarian missions in the SCS and the IOR, but also provide the fleet a nascent expeditionary capability. Interestingly, the 15,000-men Chinese Marines – who have traditionally trained for amphibious assaults – have lately begun to exercise in continental locales of Mongolia and Xinjiang, which is a pointer to China’s intention to be involved in out-of-area expeditionary missions.

Logistic Ships

The PLA Navy is also developing ‘longer legs’ through the introduction of high-endurance logistic vessels meant to provide underway replenishment (UNREP) to its principal warships far away from Chinese home bases. Since 2005, it has commissioned six advanced Type 903A (Fuchi-class) UNREP vessel with a full-load displacement of 23,000 tons. Although these are equally divided among the three PLA Navy fleets, the sequence of allocation and other developments indicate a focus on the SSF. In 2015, China launched a new rather massive 45,000 tons logistic vessel of the Qinghaihu-class, which is likely to be allocated to the SSF.

Conclusions

In tandem with China’s overall power, the capabilities of the PLA Navy’s SSF is expected to continue to grow in the coming decades, notwithstanding transient ‘hiccups’ in its economic growth. However, China’s geographically expanding economic interests into the IOR and beyond will soon overstretch its resources. Ostensibly, Beijing is well aware of this prognosis, and adopting necessary measures as part of a comprehensive long-term strategy.

Among the two overwhelming imperatives for China is to shape a benign environment in its north-eastern maritime periphery. Towards this end, in March 2013, Beijing amalgamated its various maritime agencies to form the unified Coast Guard under the State Oceanic Administration. Reportedly, China has also been trying hard to resolve its maritime boundary dispute with South Korea.

The second imperative is to sustain its naval forces in distant waters of the IOR. Towards this end, China is developing military facilities in the IOR, dovetailed with its increasing hardware sales to the regional countries. Through its ‘Maritime Silk Road’ (MSR) initiative (2013), China seems to have effectively blunted the theory of ‘String of Pearls’ (2005). Djibouti may be only the beginning. Similar facilities – supplemented by PLA Navy’s long-legged and ‘sea-based’ assets based in the SSF – would enhance China’s military-strategic and operational options manifold. Such emerging developments – and their extrapolations – need to be factored by the national security establishments of the Indo-Pacific countries.

Captain Gurpreet S Khurana, PhD, is Executive Director, National Maritime Foundation (NMF), New Delhi. The views expressed are his own and do not reflect the official policy or position of the NMF, the Indian Navy, or the Government of India. He can be reached at gurpreet.bulbul@gmail.com.

References

[i] ‘New missile destroyer joins South China Sea Fleet’, at http://eng.mod.gov.cn/DefenseNews/2015-12/14/content_4632673.htm

[ii] The CJ-10 (also called DH-10 or HN-2) is known to feature terrain contour matching (TERCOM) and data from the Chinese Beidou Navigation Satellite System for its guidance.

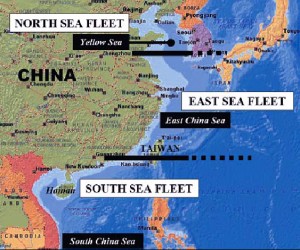

[iii] PLA Navy is divided into 3 fleets (equivalent of naval commands in India). The North Sea Fleet (NSF) adjoins the Yellow Sea/ Korean Peninsula, the East Sea Fleet (ESF) faces the East China Sea/ Taiwan, and the South Sea Fleet (SSF) overlooks the South China Sea.

[iv] The term refers to the region stretching from East Africa and West Asia to Northeast Asia, across the Indian Ocean and the Western Pacific. Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘Security of Sea Lines: Prospects for India-Japan Cooperation’, Strategic Analysis, Vol 31(1), January 2007, p139-153.

[v] All four Sovremenny-class destroyers were acquired between 1999 and 2006.

[vi] These refer to the eight Kilo-class submarines acquired between 1995 and 2005.

[vii] It refers to pennant numbers 321, 322, 323, 324, 325 and 314. The sole exception was the first Song (320) commissioned in 1999, which was inducted into the SSF, possibly since the waters off Hainan were deep enough for its dived test.

[viii] While more warships of the Type 052 not built, the Type 052C (dubbed ‘Chinese Aegis’) provided the PLA Navy for the first time, a long-range fleet air-defence capability. It is equipped with vertical-launch 90 km range HHQ-9 surface to air missiles (SAM) cued by the AESA phased-array radar with all-round coverage. The Type 052C warships commissioned later were based at the ESF.

[ix] Since long, the SSF has been home to a significant proportion of amphibious vessels and two Marine brigades, but the PLA Navy never possessed distant sealift capability. It may be recalled that China could not even contribute to the multi-nation humanitarian assistance and disaster relief (HADR) mission following the Indian Ocean Tsunami of December 2004. Ostensibly, this provided the trigger for China to build the Type 071 LPD for the SSF.

[x] Although China’s plans to build Yalong bay base was known for some years, the report was the first to provide its details. Richard D Fisher Jr, “Secret Sanya – China’s new nuclear naval base revealed”, Jane’s Intelligence Review, 15 April 2008, at http://www4.janes.com/subscribe/jir/doc_view.jsp?K2DocKey=/content1/janesdata/mags/jir/history/jir2008/jir10375.htm@current&Prod_Name=JIR&QueryText

[xi] Called Yongxing Dao by the Chinese, Woody Island is located 150 nautical miles south-east of Hainan, and is the largest island of the Paracel group. In the 1980s, it accommodated a mere helicopter pad. In 1990, China undertook land reclamation to construct a 1,200-feet airstrip to operate jet fighters.

[xii] Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘China’s South Sea Fleet Gains Strength: Indicators, Intentions & Implications, India Strategic, Vol. 3(10), October 2008, p.48, at http://www.indiastrategic.in/topstories183.htm

[xiii] James C Bussert, ‘Hainan is the Tip of the Chinese Spear’, Signal, June 2009, at http://www.afcea.org/content/?q=hainan-tip-chinese-navy-spear

[xiv] Edward Wong, ‘Chinese Military Seeks to Extend Its Naval Power’, The New York Times, 23 April 2010, at http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/24/world/asia/24navy.html?_r=0

[xv] These refer to the hierarchal levels of China’s administrative divisions: Province (first level), Perfecture City (second level) and County (third level).

[xvi] ‘Sansha new step in managing S. China Sea’, Global times, 25 June 2012, at http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/716822.shtml

[xvii] Mike Ives, ‘Vietnam Objects to Chinese Oil Rig in Disputed Waters’, The New York Times, 20 Jan 2016, at http://www.nytimes.com/2016/01/21/world/asia/south-china-sea-vietnam-china.html?_r=0

[xviii] ‘Asia-Pacific rebalance 2025: Capabilities, Presence and Partnerships’, Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) Report , 20 January 2016, p.VI, at http://csis.org/files/publication/160119_Green_AsiaPacificRebalance2025_Web_0.pdf

[xix] ‘China defence: Work starts on second aircraft carrier’, BBC News, 31 December 2015, at http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-china-35207369

[xx] ‘Beijing Plans Aircraft Carrier Patrols in Disputed South China Sea’, Sputnik International News, 29 January 2016, at http://sputniknews.com/asia/20160129/1033950259/aircraft-carrier-south-china-sea.html

[xxi] ‘21st Chinese naval escort taskforce wraps up visit to Bangladesh’, China Military Online, 2 February 2016, at http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2016-02/02/content_6885175.htm

[xxii] Carlyle A. Thayer, ‘Background Briefing: China’s Air Strip on Woody Island’, C3S Paper No.2055, 20 October 2014, at http://www.c3sindia.org/uncategorized/4568

[xxiii] Jeremy Bender, ‘China’s New Submarines Could Create Problems for the US Navy’, Business Insider, 7 April 2015, at http://www.businessinsider.in/Chinas-new-submarines-could-create-problems-for-the-US-Navy/articleshow/46844459.cms

[xxiv] AIP enhances the operational effectiveness of a conventional submarine substantially by enabling it to remain submerged up to as long as three weeks.

[xxv] Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘PLA Navy’s Submarine Arm ‘Stretches its Sea-legs’ to the Indian Ocean’, National Maritime Foundation , New Delhi, 21 November 2014, at https://independent.academia.edu/khurana

[xxvi] Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘ China’s Yuan-class Submarine Visits Karachi: An Assessment’, National Maritime Foundation , New Delhi, 24 July 2014, at https://independent.academia.edu/khurana

[xxvii] The fourth Type 071 LPD Yimengshan (988) commissioned in February 2016 was inducted in the East Sea Fleet. Andrew Tate, ‘The PLAN commissions fourth Type 071 LPD’, IHS Jane’s Navy International, 3 February 2016, at http://www.janes.com/article/57683/the-plan-commissions-fourth-type-071-lpd

[xxviii] Mike Yeo, ‘China Commissions First MLP-Like Logistics Ship, Headed For South Sea Fleet’, USNI News, 14 July 2015, at http://news.usni.org/2015/07/14/chinas-commissions-first-mlp-like-logistics-ship-headed-for-south-sea-fleet Also see, Gurpreet S Khurana, ‘Sea-based’ PLA Navy may not need ‘String of Pearls’ in the Indian Ocean’, Centre of International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), 12 August 2015, at https://cimsec.org/sea-based-pla-navy-may-not-need-string-pearls/18053

[xxix] In 2014, the Marines conducted the first such training in the grasslands of Inner Mongolia, followed by the second one in December 2015 in the deserts of Xinjiang. The latter came in wake of Beijing passing a new unprecedented legislation that permits the PLA to undertake counter-terrorism missions overseas. Michael Martina and Greg Torode, ‘Chinese marines’ desert operations point to long-range ambitions’, Reuters, 14 January 2016, at http://www.reuters.com/article/us-china-military-marines-idUSKCN0US2QM20160114

[xxx] Wu Jiao and Pu Zhendong, ‘Nation merging maritime patrol forces’, China Daily, 11 March 2013, at http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013npc/2013-03/11/content_16296448.htm

[xxxi] In 2014, China and South Korea agreed to initiate a dialogue to delineate their maritime boundary outstanding for two decades. The preliminary talks were held in December 2015. ‘South Korea, China Discuss Fisheries and Boundary Conflict’, Maritime Executive, 22 December 2015, at http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-12/14/c_134916062.htm