By Bruce Stubbs

“A requirement is a requirement, pure and simple.”

—Lieutenant General Karsten Heckl, USMC

“One man’s requirement is like another man’s wish.”

—Admiral Frank B. Kelso II, USN (retired)

A Team of Rivals

The United States Marine Corps has an outsized effect on Navy force planning. While the Navy and the Marines exhibit a sincere and genuine single team spirit conducting global naval operations, they are a fierce team of rivals when determining the requirements for amphibious ships (also known as “amphibs”), which the Navy funds for their construction and operation.

Soon after becoming Marine Corps Commandant, General David H. Berger announced a headline-grabbing transformation of the Corps in his July 2019 Commandant’s Planning Guidance. In its new role, the Marines would operate inside actively contested maritime spaces to conduct sea denial and assured access missions with a particular focus on the Indo-Pacific theater. In March 2020 Berger further explained his concept in Force Design 2030. Berger’s guidance declared that the Navy’s large amphibs were too vulnerable and too expensive to risk in combat, the Marines’ requirement for 38 or 34 large amphibs was no longer valid, and the Marines had a new requirement for small, agile amphibs.

His unprecedented, if not historic, transformational initiative sparked a yearslong controversy over two inter-related issues. First, Force Design 2030 punctured the Corps’ rationale for Navy’s large amphibs, which the two sea services refer to as either “big deck” or “small deck” ships. Second, the initiative handed the Navy a multi-billion dollar bill to construct and operate a new class of amphibs designated eventually as the Medium Landing Ship.

Issue#1: Number of Large Amphibious Ships

Shifting Requirements

From Berger’s determination that large amphibs were too vulnerable and too expensive, it logically followed what Mark Cancian, an analyst at the Center for Security and International Studies and a retired colonel of Marines, concluded. If the Marines believed their “future lay in small amphibious ships, then the Pentagon should limit the building of large amphibious ships.” The Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office—a powerful analytical office reporting directly to the Secretary of Defense—took notice of this contradiction in the Marines’ transformation planning.

Since the end of the Cold War, the Marines’ requirement for large amphibs has been an issue for the Navy. Former Secretary of Defense Robert M. Gates (2006-2011) in May 2010 explained why: “We have to take a hard look at where it would be necessary or sensible to launch another major amphibious landing again – especially as advances in anti-ship systems keep pushing the potential launch point further from shore.… what kind of amphibious capability do we really need to deal with the most likely scenarios, and then how much?”

Echoing Gates’ arguments, Jerry Hendrix, a senior fellow at the Sagamore Institute and a retired Navy captain, stated that the Marine Corps has “been less than convincing on the role of amphibs in the future fight” and the need for joint forcible entry and amphibious assault. He observed, ” … outside of beaches on the Korean Peninsula … where [are they] going to be doing amphibious assault … what [is] the argument” for this capability? According to Cancian, the Marines have not “offered a strong wartime rationale for 31 large amphibious ships.”

Trump’s Defense Secretary Wants Fewer Large Amphibious Ships

By early 2020, it appeared Secretary of Defense Mark Esper had determined that the requirement for opposed amphibious landings was diminishing. He wanted a warfighting strategy to drive amphibious force planning, not a peacetime forward presence strategy. So, Esper directed his staff to conduct a new amphib study as a component of a larger study on the Navy’s total ship requirements. Completed in October 2020, the Future Navy Force Study served as the basis for the first Trump administration’s last Navy shipbuilding plan, submitted to Congress in December 2020. Esper’s unprecedented tasking of his staff to conduct this study resulted in the Navy losing control over its force planning efforts for about eight months.

This plan had dire consequences for the Marines. It reduced the number of large amphibs by calling for a range of 9 to 10 “big deck” ships and a range of 52 to 57 for all other amphibs. Ronald O’Rourke, the respected Congressional Research Service analyst, suggested that this range could be divided into 19 or fewer “small deck” ships and 28 to 30 of the new Light Amphibious Warship. The combined total of “big deck” and “small deck” ships would be well under 30, which was unacceptable to the Marines.

Biden’s Navy Secretary Also Wanted Fewer Large Amphibious Ships and Another Study

On June 17, 2021, new Secretary of the Navy Carlos Del Toro released the fiscal year 2022 shipbuilding plan. It called for 8 to 9 “big deck” amphibs, 16 to 19 “small deck” amphibs, and 24 to 35 new Light Amphibious Warships, which in 2024 the Navy redesignated the Medium Landing Ship. Also in June, the Navy and the Marines completed another amphib study which determined a requirement for 28 to 31 large amphibs. For the Marines, “31-amphibs” became their red-line for large amphibs, contradicting the Secretary’s range of 24 to 29 in the fiscal year 2022 shipbuilding plan.

In September 2021 Del Toro directed another evaluation of amphibious ship requirements called the Amphibious Force Requirement Study for delivery by March 2022. (Del Toro delayed submitting this study to Congress until December 2022.) By February 2022, Admiral Michael Gilday, the Chief of Naval Operations, publicly stated that the fiscal year 2023 shipbuilding plan would include, “probably nine big deck amphibs and another 19 or 20 [“small deck” ships] to support them.” Gilday’s numbers indicated a range of 28 to 29 for the large amphibs. A few months later, Del Toro released the fiscal year 2023 shipbuilding plan in April, presenting an unhelpful package of three alternative plans for a range of 7 to 9 “big deck” ships and 15 to 26 “small deck” ships for a total between 22 to 26 by fiscal year 2045. The reduction in large amphibs would prevent the Marines from simultaneously deploying three Marine Expeditionary Units.

While the Biden administration signaled it did not fully support the Marines’ requirements, some in Congress did. Representative Joe Courtney (D-Conn.) and Representative Rob Wittman (R-Va.) introduced a bill to maintain 31 large ships. In late July 2022, Gilday released his Navigation Plan 2022 which called for 31 large amphibious ships and 18 Light Amphibious Warships.

Congress Is Incensed and Supports the Marines

By April 2022, Congress still had not received Del Toro’s Amphibious Force Requirements Study. A dispute, which became a stand-off between the Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation office and the Navy, caused the delay. This office wanted the Navy to reconsider portions of the report, but the Navy declined, and so the study languished. By December, Congress had had enough and passed the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2023 with a statutory requirement for not less than 31 large amphibs, including 10 “big deck” and 21 “small deck” ships. This Act also required the Navy Secretary to ensure that the Commandant’s views are given appropriate consideration before a major decision is made by an element of the Navy Department outside the Marine Corps on a matter that directly concerns amphibious force structure and capability. In addition, the Act assigned directed responsibility to the Commandant for developing the requirements relating to amphibs. Del Toro finally sent the classified Amphibious Force Requirements Study to Congress in late December 2022. No sooner than Congress received this study, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin directed a “redo” with little Navy objection, which according to Politico, increased the Marines’ frustration.

Navy Secretary Announces an Amphibious Strategic Pause

Del Toro publicly stated in February 2023 that the Navy was taking a “strategic pause” from buying the “small deck” ships. He explained that the Navy needed additional time to determine the mix and number of amphibs before resuming procurement. The Secretary’s announcement was somewhat disingenuous as the Secretary had already initiated a de facto strategic pause in his April 2022 submission of the fiscal year 2023 shipbuilding plan and the fiscal year 2030 budget. According to Politico, the Marines were furious over this outcome. Gilday explained that lack of funding was the “driving issue” for the decision not to fund any more of these $1.8 billion “small deck” ships.

Congress Intervenes Again for the Marines

By April 2023, Del Toro’s strategic pause not to buy “small deck” amphibs had greatly annoyed the Senate Armed Services Committee. A month later the Committee reproached Del Toro in a June 13th letter for not responding to its questions regarding the Navy’s non-compliance with the statutory requirement to maintain 31 large amphibious ships. The senators saw no planning in the Navy’s fiscal year 2024 shipbuilding plan to achieve this force-level goal. Co-signed by 14 Democratic and Republican senators, the letter stated, “The Navy’s current plan not only violates the statutory requirement, but also jeopardizes the future effectiveness of the joint force, especially as we consider national security threats in the Indo-Pacific.” The letter continued that the Del Toro had until June 19th to respond with an updated shipbuilding plan for fiscal year 2024, and a pointed reminder that the 31-ship requirement “is not a suggestion but a requirement based on the assessed needs of the Navy and the Marine Corps.” In early August USNI News reported that the strategic pause was still in effect. At her September 2023 confirmation hearings to become the 33rd Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Lisa Franchetti endorsed the Marines’ requirement for 31 large amphibious ships.

Congress Helps Thwart an “Existential Threat” from the Navy Secretary

As the Marines entered 2024, the debate over the number of large amphibious ships remained unresolved. Lieutenant General Karsten Heckl, Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration, called the amphib shortage the Marines’ “single biggest existential threat.” In March, the Defense and Navy Departments eliminated this threat by ending the two-year “strategic pause” for procuring “small deck” amphibs. The Navy’s budget submission for fiscal year 2025 and its fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan, both approved by the Defense and Navy Departments, included the procurement of “small deck” ships. In addition, these documents commenced the procurement of a new class of Medium Landing Ships. The Biden Administration had caved to Congress and ended the almost two-year strategic pause.

Issue #2: The Unaffordable and Unsurvivable Ship

Marines Give The Navy A Shipbuilding Bill

Berger’s guidance called for a new class of Navy amphibious ships that were “smaller, more lethal, and more risk-worthy platforms” to shuttle Marines around archipelagic islands. The Marines would “shoot” anti-ship cruise missiles from one island and then “scoot” to another island using the new amphibs as “water taxis” to “shoot” once more. In 2020 the Navy designated this new amphib as the Light Amphibious Warship. The Navy anticipated procuring a class of 28 to 30 ships with a crew of “no more than 40 Navy Sailors” at a “unit procurement cost of less than $100 million.”

Almost immediately the Navy and the Marine Corps clashed over the ship’s capabilities and costs. The Navy wanted a “survivable ship,” while the Marines wanted an operational ship as fast as possible, as well as one built to civilian standards and not military standards to reduce construction costs. Their disagreement delayed the delivery of first ship to “fiscal year 2023 and then to fiscal year 2025.” By January 2024, the Navy released its request for proposals for the first six of these new class of ships for delivery in 2029. The Navy asked for a ship that could lift 75 Marines and 600 tons of equipment with a “cargo area of about 8,000 square feet, a helicopter pad, a 70-person crew, spots for six .50-caliber guns and two 30mm guns.” The Navy also wanted the ship to be under 400 feet long, a draft of no more than 12 feet, a 14-knot endurance speed, and roll on/roll off beaching capability.

By April 2024, the Navy had re-designated the ship as a Medium Landing Ship with an increased estimated unit procurement cost of roughly $150 million in constant fiscal year 2024 dollars for the first 8 ships and a class size of 35 ships by 2043. The Navy estimated that 55 of these ships would “cost less than $200 million per ship, on average.” The Congressional Budget Office, however, projected the average cost at $350 million per ship.

In December 2024, the Navy received industries’ responses to its January 2024 request for proposals. After seeing the costs, the Navy immediately canceled its request. Gobsmacked, Nickolas Guertin, the assistant secretary of the navy for research, development and acquisition, stated the request for bids, “came back with a much higher price tag. … we had to pull that solicitation back and drop back and punt.” In January 2025, the Navy punted and began looking for “existing, private-sector designs” requiring minor modifications for conversion at a small cost.

In 2025, Unanswered Questions Remain About the New Amphibious Ship

The central issue about the procurement of the Medium Landing Ship remains its construction cost, which is dependent on whether the Navy builds the ship to commercial or naval warfare standards, which is, in turn, dependent on the ship’s final operational concept. Building to commercial standards lowers construction costs. The operational concept remains unclear whether these ships will operate in a benign environment. Will they only operate in the pre-crisis phase or after hostilities have commenced and these ships find themselves in contested waters? Moreover, if the Marines intend to resupply its forces as well to relocate them during the conflict, it is highly likely that these ships would be vulnerable to detection and attack.

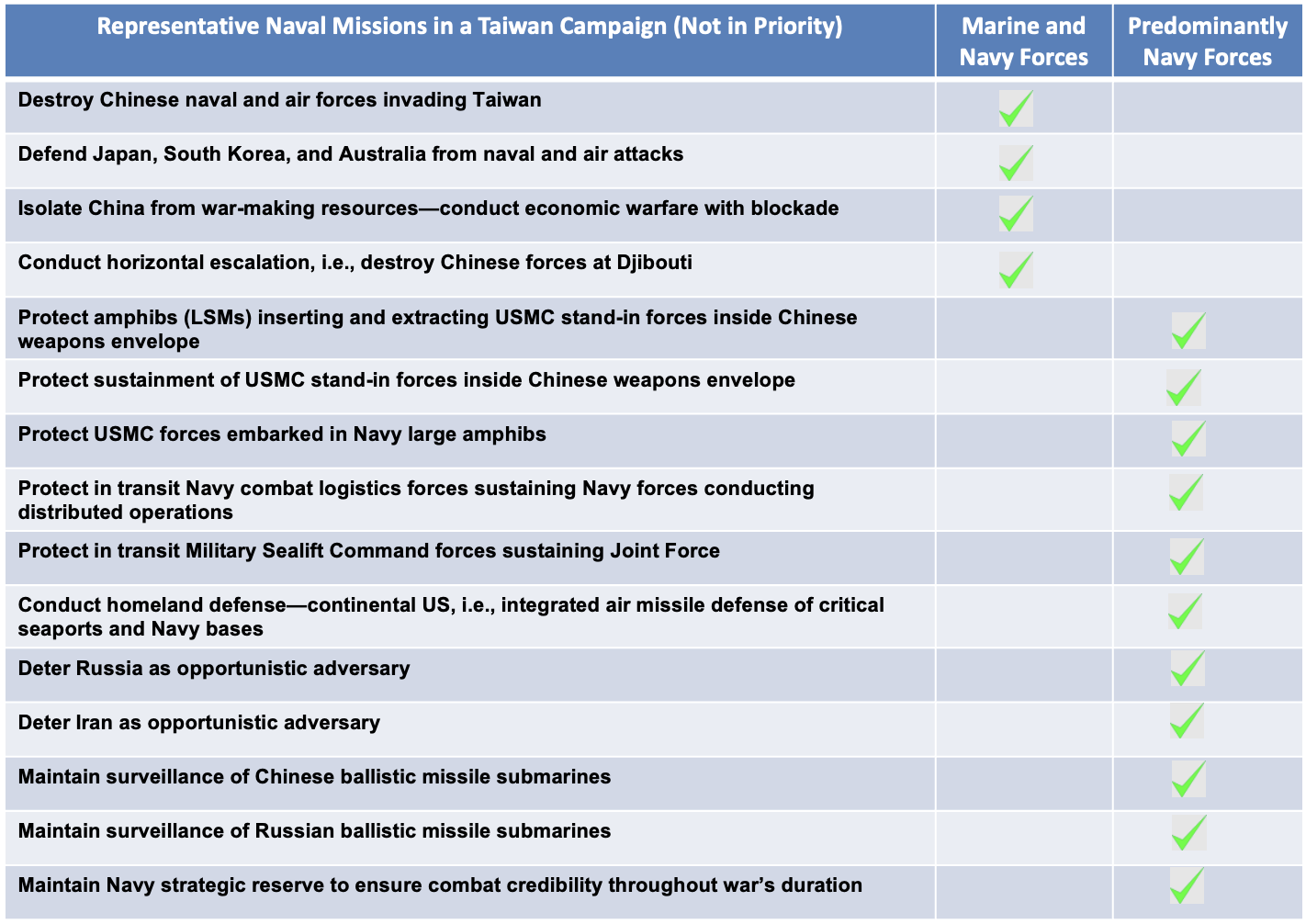

Consequently, the Navy will have a mission requirement to protect and sustain the Marines operating as stand-in forces, placing another demand on the Navy to provide forces while also conducting other high priority missions (see Table 1). In April 2024 the Congressional Budget Office reported that “A ship that is not expected to face enemy fire in a conflict could be built to a lesser survivability standard, with fewer defensive systems than a ship that would sail in contested waters during a conflict.”

Table 1: A comparison of potential missions for the Department of the Navy during a conflict over Taiwan, divided into missions shared by the Navy and Marine Corps and missions that would be assigned to predominantly Navy forces. (Author graphic)

Table 1: A comparison of potential missions for the Department of the Navy during a conflict over Taiwan, divided into missions shared by the Navy and Marine Corps and missions that would be assigned to predominantly Navy forces. (Author graphic)

Perhaps in an attempt to strengthen the argument that the Navy should construct these ships to commercial standards, the fiscal year 2025 shipbuilding plan did not classify the Medium Landing Ship as an “amphibious warfare ship.” Instead, in a puzzling decision it was categorized as a “command and support” vessel, despite its requirement to land Marines on beaches to conduct kinetic operations.

Wrap-Up

The Navy and Marine Corps Have Different Priorities and Agendas

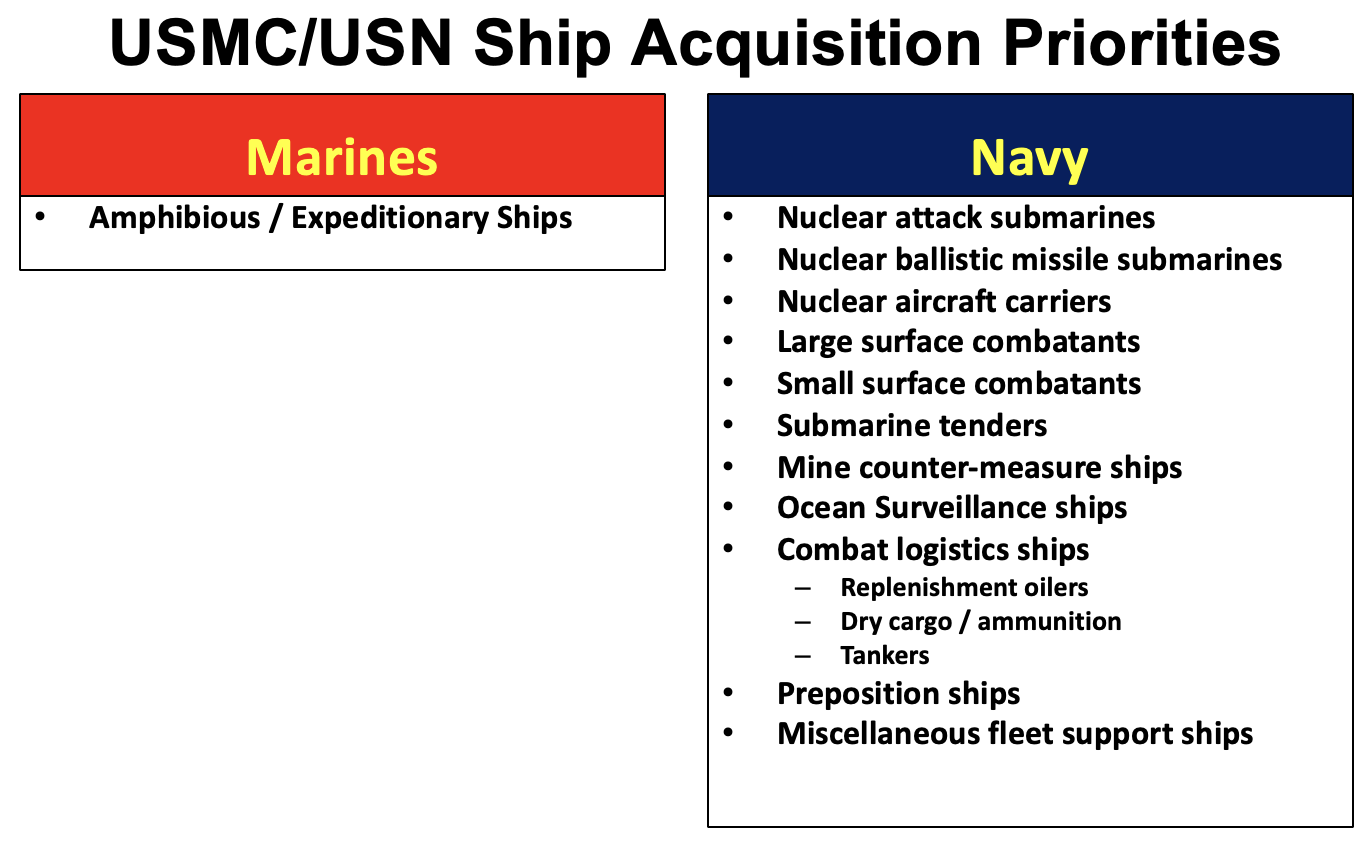

The Navy and the Marine Corps co-exist on some important core common tasks and viewpoints, reinforced by established historical, political, legal, and bureaucratic frameworks. The Marine focus on forward presence, forcible entry, and expeditionary warfare employing the Navy’s amphibs. Whereas for the Navy, expeditionary warfare is merely one among many Navy warfare functions to include anti-air warfare, anti-surface ship warfare, anti-submarine warfare, strike warfare, special operations warfare, mine and countermine warfare, electronic and information warfare, strategic deterrence, combat logistics, and sealift for Joint Force logistic sustainment. For the Marines, amphibs are a priority. For the Navy, however, ballistic missile submarines, attack submarines, aircraft carriers, large surface combatants, small surface combatants, auxiliary ships, logistics ships, oilers, and minesweepers are all priorities as well as amphibs (see Table 2).

Table 2: A comparison of ship acquisition priorities between the Navy and Marine Corps. (Author graphic)

Table 2: A comparison of ship acquisition priorities between the Navy and Marine Corps. (Author graphic)

The Navy does not get to focus on just one type of ship and it is responsible for a wide range of warfighting functions. In contrast, the Marine Corps has a much narrower set of responsibilities. When force structure priorities differ between the Navy and Marines, the Navy finds itself in an awkward position between one side—composed of the Office of Management and Budget, the Department of Defense, and the Department of the Navy—and the other side comprised of the Marines and Congress. Such triangulation can lead to an almost unmanageable situation whereby the Navy loses control of the planning for its future, which actually occurred in 2019.

Gilday noted that the Navy “must prioritize programs most relevant” to a conflict with China. What can be more relevant to a conflict with China than logistics, especially with a U.S. Navy conducting distributed operations, likely without the availability of Guam. Lines of communication will stretch for thousands of miles from the U.S. homeland to the operating areas. These sea lines of communication, as well as U.S. ports, will require protection because China has the means and the will to interdict and sever these lines to isolate U.S. fighting forces and prevent their sustainment. Logistics ships to sustain combat operations, submarine tenders to rearm submarines, and oilers to refuel the Navy’s distributed forces across the vast Pacific distances may be more needed by the Navy than a new class of 35 amphibs. In February 2024 Admiral Samuel J. Paparo, Jr., then the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, stated that the Navy’s Combat Logistics Force, which supports and sustains the Navy’s distributed maritime operations with “beans, bullets, and black oil” is operating on “narrow margins” with insufficient ships for a war with China. He specifically cited inadequate numbers of oilers. Admiral Paparo also noted that the Chinese consider the U.S. Navy’s logistics capabilities a critical vulnerability with his statement that “When we run [war]games, the red team goes for the Combat Logistics Force every single time.” The Navy’s lack of strategic guidance hindered a comprehensive understanding of this and other thorny force planning issues, consequently strategic force priorities were often set on the fly.

The differences between the two sea services are real, and relations about Department of the Navy funding priorities have often been fractious and kept in-house. A major exception underscoring this sometime discordant relationship occurred in December 1995. General Carl E. Mundy, Jr., U.S. Marine Corps (retired), who served as Commandant, fired a salvo at the Navy for allegedly short-changing the Marine Corps for its fair share of the Navy Department’s budget. Admiral Frank B. Kelso, II, U.S. Navy (retired), Chief of Naval Operations (1990-1994), reminded Mundy that the Marines cannot ignore the “total requirements of the Navy” beside supporting the Marines in the “littorals.”

Conclusion

When the Marines believe their future is in jeopardy, which certainly was the case with this confrontation over 31-large amphibs and the fight for 35 new smaller amphibs, the Marines do not hesitate to seek Congress’ intervention on their behalf. Besides calling the reduction in large amphibs an existential threat to the Marines’ existence, General Heckl thundered, “Our identity is elemental to who we are as Marines. We are soldiers of the sea. We are the nation’s naval expeditionary force. And we just can’t lose that.” His statements reflected the Marine Corps’ laser focus on its own force structure, rather an appreciation of the bigger picture.

Advocates for any of the services can sometimes believe so passionately in the potential effectiveness of their particular service with its “unique” weapon systems, ships, or aircraft that “they find it difficult to appreciate the fuller pattern of a future war and the unforgiving priorities dictating resource allocation.” Their degree of identification with their service may “discourage viewpoints and thinking oriented toward the best interests” of the Joint Force as a whole.” The Marines’ success in setting the goal of 31 large amphibs and a new class of amphibs illustrates the powerful influence the Marines can and will exert over the Navy’s force planning process to achieve their objectives. The nation can only hope that the recent outcomes in amphib numbers that the Marines have achieved in coordination and cooperation with congressional and industrial influence will produce the desired benefit to America’s national defense, and not shortchange other high-priority requirements.

The Marine Corps has a well-deserved special place in the hearts of Congress and the American people—a sentiment that can defy the logic of Navy force planning, and the intentions of any administration to prioritize the nation’s defense requirements. The Marines—thanks to Congress—have a big vote in Navy force planning. Short of the Marine Corps becoming an independent armed service outside the Department of the Navy, the Navy, as best as it can, just has to live with a pertinacious Marine Corps — or it can borrow a page from the Marine Corps’ playbook.

Prior to his full retirement as a member of the U.S. senior executive service, Bruce Stubbs had assignments on the staffs of the secretary of the Navy and the chief of naval operations from 2009 to 2022. He was a former director of Strategy and Strategic Concepts in the OPNAV N3N5 and N7 directorates. As a career U.S. Coast Guard officer, he had a posting as the Assistant Commandant for Capability (current title) in Headquarters, served on the staff of the National Security Council, taught at the Naval War College, commanded a major cutter, and served a combat tour with the U.S. Navy in Vietnam during the 1972 Easter Offensive. The author drew upon his forthcoming publication, Cold Iron: The Demise of Navy Strategy Development and Force Planning, to compose portions of this commentary.

Featured Image: Ships of the Kearsarge Amphibious Ready Group sail in formation. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Corbin J. Shea/Released)