This article is part of a series hosted by The Strategy Bridge and CIMSEC, entitled #Shakespeare and Strategy. See all of the entries at the Asides blog of the Shakespeare Theatre Company. Thanks to the Young Professionals Consortium for setting up the series.

The Irish poet Thomas Moore wrote:

Like the vase, in which roses have once been distill’d — You may break, you may shatter the vase, if you will, But the scent of the roses will hang round it still.

So it is with David Greig’s masterful play Dunsinane, ostensibly a modern sequel to Shakespeare’s Macbeth, but in reality a morality play about the failures of a post-invasion military operation. The play lingers with you, not with the scent of roses, but with the putrid stench of a body decaying before your eyes, ears and nose. That is not a reflection of this stunningly brilliant play as written or acted. Rather, it is the grim reality of the catastrophic consequences when political and military leaders lack a vision prior to embarking on a major military operation.

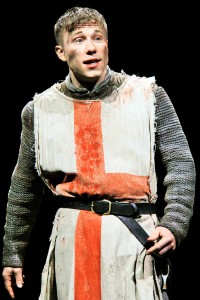

While CIMSEC has elected to publish essays about the play within the context of military strategy, no essay should omit mention of the truly extraordinary performances of each cast member, especially Darrell D’Silva as Siward, Siobhan Redmond as Gruach (aka Lady Macbeth), and Tom Gill as the boy soldier aged by war. These actors and the entire cast brought an already superbly written play to life.

The opening scenes of Dunsinane take place in the closing scenes of “Macbeth,” as Great Birnam Wood is marching toward the Scottish king’s castle.1 The English army is led by the English/Danish Earl of Northumbria, Siward. Joining his army are King Malcolm, who claims the Scottish throne himself, and Macduff, Thane of Fife, both of whom have been living in exile in England. Now they have persuaded a foreign army to seize power for them.

Dunsinane engages the audience to determine whether or not it might have been right to depose Macbeth. In the final act of the original play Siward repeatedly demonizes Macbeth as a tyrant – a word used by Siward’s son before he’s killed by Macbeth. In Dunsinane, Macbeth is viewed by Gruach, admittedly the “fiend-like queen,” as a good king who ruled well for fifteen years. Siward’s victory already has a cost – the life of his son Osborn. The loss of his son is only Siward’s first lesson in what will be a costly and bloody war. The second is lost to him, and perhaps to anyone not paying close attention in Dunsinane. The body of King Macbeth, the vanquished “tyrant,” is slowly carried on stage by a ceremonial guard with all the dignity of a ruler, his body cleanly covered by a flag. As it is carried off, the body of Osborn arrives covered in a cheap bloody shroud as Siward kneels over him. In death, Macbeth has been given legendary status among the Scots in their fight against the invading English; Osborn will quickly be forgotten by his contemporary English army and history.

Beyond the wars of lords and generals, the English footsoldiers also misunderstand their Scottish counterparts. Reaching the keep after losing twelve soldiers, more soldiers are injured by a single Scottish archer’s hopeless attack. “Why did he fight? Why did he not surrender?” one soldier asks the others. The playwright could have inserted the response, “Because some insurgents won’t quit or see reason,” but that would have been unnecessary.

Victorious in battle over Macbeth, the glory and the raison d’etre quickly evaporate. He is stymied almost as soon as the war is supposedly won. In one of the most demoralizing scenes, MacDuff tries to explain to the intelligent but ignorant Siward the map of Scotland, its factions, and to whom the factions are loyal (Malcolm or Gruach.) Siward has already failed in his mission as he has never seen them before. Why, one might ask, was this Earl not already familiar with the Scottish situation that is on his border. Siward, thinking only in terms of a short-term invasion, has failed to learn the geopolitical situation and plan for the potential consequences.

One might easily think of Iraq or Afghanistan as current examples, but there are micro-examples as well. Last summer I had a discussion with an individual about their pending posting on the other side of the world and started asking the questions Siward should have asked. Instead of thoughtful reflection, the individual’s response, that the study of history and politics had no value and that only tactical issues were important, further revealed how apathetic and unaware warfighters can be of the facets of war . The consequences of that particular posting have borne out the “Siwardness” of that individual’s abilities.

Siward has no long-range plan to “win” though many in the play question how that might be defined. At first, he states that he has come to bring order. However, as Gruach argues, “We had peace until you came along.” Later, the Hamid Karzai-like Malcolm, draped in shimmering golden robes, and Gruach fight their civil war as Siward not only shifts his support from one to the other, but also the reason for the war. From bringing order, the insurgency begins to result in more and more English lives lost. Siward now proclaims the war is about justice. The soldiers, having prematurely cheered for their victory at the keep are now questioning why they are still there. With time on their hands, they begin taking local treasures or passing their time using a religious mural – and eventually a local girl – as target practice. This takes place below the permanently staged giant Celtic cross. Siward is oblivious to the activities of his soldiers and the local populace except for the mounting deaths, until he himself begins to take drastic and more costly measures against the Scots which, in turn, only results in a broader-based insurgency.

Eventually, Siward suggests that, “We will go to the clans and make a parliament,” an anachronism in age of Macbeth and Siward, but still foreign to the Scots in the play and one half-expects the term Loya Jirga to be used by the playwright. Although it appears a Siward-suggested agreement is reached, the factions quickly fall apart and the war is renewed. Both Gruach and Malcolm realize that the increasingly-fatigued Siward has no idea how to win or what “winning” is. They realize before he does that he must step aside for another leader. Eventually, Siward recognizes that the war is futile and hands over his sword to his successor, the pragmatic realist Lord Egham, as he personally delivers the bloody body parts that once were Gruach’s son and heir to the throne.

The ending of Dunsinane begs for its own sequel. How would Egham continue the operations? With whom would he ally? How would he define victory? Would he bring the troops homes?

As this play demonstrates, wars aren’t won or lost by the bravery of soldiers; they’re won or lost by the political and military leaders who fail to understand history, politics, cultures, linguistics, and, with Dunisnane, plays. Dunsinane ought to be performed at every military academy and war college, the Pentagon, and for policymakers of any nation. But if history tells us anything, the audience would applaud loudly at the conclusion of the play, but the lessons of Dunsinane would soon be forgotten and the vases shattered once again.

Claude Berube teaches naval history at the United States Naval Academy and was an intelligence officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve serving twice overseas. He is the author of more than 50 articles and co-author three non-fiction books. He is the author of the Connor Stark novels published through Naval Institute Press (Syren’s Song, the sequel to The Aden Effect, will be published this fall.) The views expressed are his own and not those of the Department of the Navy.

1. Thus fulfilling one of witch’s predictions foretelling of Macbeth’s eventual defeat. . In the only unfortunate scene, the audience laughs as the English army mobilizes in Great Birnam Wood, disguising themselves as trees and shrubs. The way the scene is presented and the audience’s reaction undermine what is actually an effective means of military deception – how exactly do you hide an army just a few miles from the enemey’s keep? It is a version of naval dazzle camouflage or of the efforts prior to D-Day to confuse the Nazis about the originating point of the real cross-channel invasion.

We stood on the Essex shore a mess of shingle,

We stood on the Essex shore a mess of shingle,