By Marjorie Greene

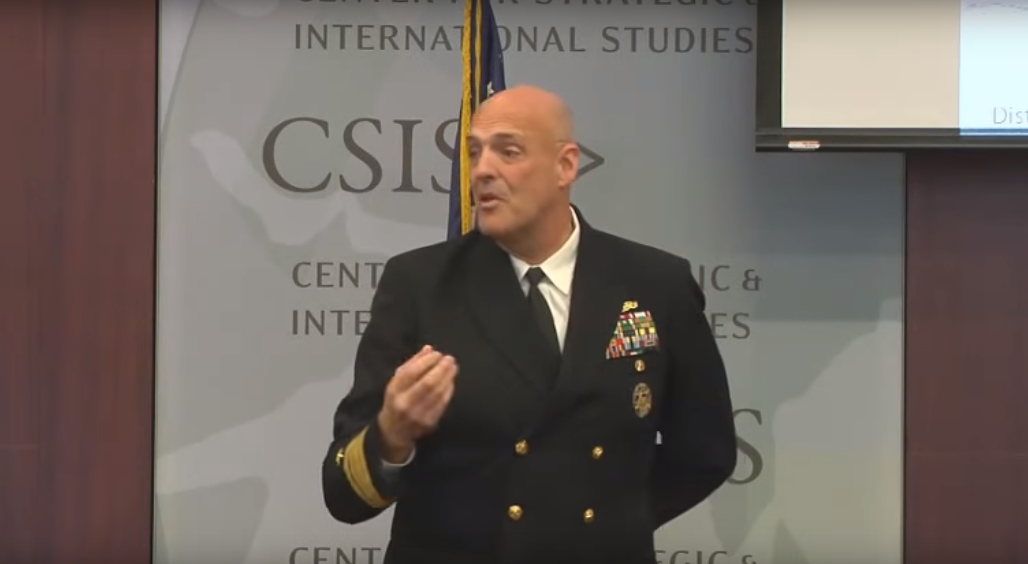

The U.S. Navy’s Unmanned Systems Directorate, or N99, was formally stood up this past September with the focused mission of quickly assessing emerging technologies and applying them to unmanned platforms. The Director of Unmanned Warfare Systems is Rear Adm. Robert Girrier, who was recently interviewed by Scout Warrior, and outlined a new, evolving Navy Drone Strategy.

The idea is to capitalize upon the accelerating speed of computer processing and rapid improvements in the development of autonomy-increasing algorithms; this will allow unmanned systems to quickly operate with an improved level of autonomy, function together as part of an integrated network, and more quickly perform a wider range of functions without needing every individual task controlled by humans. “We aim to harness these technologies. In the next five years or so we are going to try to move from human operated systems to ones that are less dependent on people. Technology is going to enable increased autonomy,” Admiral Girrier told Scout Warrior.

Forward, into Autonomy

Although aerial drones have taken off a lot faster than their maritime and ground-based equivalent, there are some signs that the use of naval drones – especially underwater – is about to take a leap forward. As recently as February this year, U.S. Defense Secretary Ash Carter announced that the Pentagon plans to spend $600 million over the next five years on the development of unmanned underwater systems. DARPA (the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency) recently announced that the Navy’s newest risk taker is an “unmanned ship that can cross the Pacific.”

DARPA’s initial launch and testing of Sea Hunter. (Video: DARPA via YouTube)

Called the Sea Hunter, the vessel is a demonstrator version of an unmanned ship that will run autonomously for 60 – 80 days at a time. Known officially as the Anti-Submarine Warfare Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV), the program started in 2010, when the defense innovations lab decided to look at what could be done with a large unmanned surface vessel and came up with submarine tracking and trailing. “It is really a mixture of manned-unmanned fleet,” said program manager Scott Littlefield. The big challenge was not related to programming the ship for missions. Rather, it was more basic – making an automated vessel at sea capable of driving safely. DARPA had to be certain the ship would not only avoid a collision on the open seas, but obey protocol for doing so.

As further evidence of the Navy’s progress toward computer-driven drones, the Navy and General Dynamics Electric Boat are testing a prototype of a system called the Universal Launch and Recovery Module that would allow the launch and recovery of unmanned underwater vehicles from the missile tube of a submarine. The Navy is also working with platforms designed to collect oceanographic and hydrographic information and is operating a small, hand-launched drone called “Puma” to provide over-the-horizon surveillance for surface platforms.

Both DARPA and the Office of Naval Research also continue to create more sophisticated Unmanned Aircraft Systems. DARPA recently awarded Phase 2 system integration contracts for its CODE (Collaborative Operations in Denied Environment) program to help the U.S. military’s unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) conduct dynamic, long-distance engagements against highly mobile ground and maritime targets in denied or contested electromagnetic airspace, all while reducing required communication bandwidth and cognitive burden on human supervisors.

CODE’s main objective is to develop and demonstrate the value of collective autonomy, in which UAS could perform sophisticated tasks, both individually and in teams under the supervision of a single human mission commander. The ONR LOCUST Program allows UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) to stay in formation with little human control. At a recent demonstration, a single human controller was able to operate up to 32 UAVs.

The Networked Machine…

The principle by which individual UAVs are able to stay in formation with little human control is based on a concept called “swarm intelligence,” which refers to the collective behavior of decentralized, self-organized systems, as introduced by Norbert Wiener in his book, Cybernetics. Building on behavioral models of animal cultures such as the synchronous flocking of birds, he postulated that “self-organization” is a process by which machines – and, by analogy, humans – learn by adapting to their environment.

The flock behavior, or murmuration, of starlings is an excellent demonstration of self-organization. (Video: BBC via YouTube)

Self-organization refers to the emergence of higher-level properties and behaviors of a system that originate from the collective dynamics of that system’s components but are not found in nor are directly deducible from the lower-level properties of the system. Emergent properties are properties of the whole that are not possessed by any of the individual parts making up that whole. The parts act locally on local information and global order emerges without any need for external control. In short, the whole is truly greater than the sum of its parts.

There is also a relatively new concept called “artificial swarm intelligence,” in which there have been attempts to develop human swarms using the internet to achieve a collective, synchronous wisdom that outperforms individual members of the swarm. Still in its infancy, the concept offers another approach to the increasing vulnerability of centralized command and control systems.

Perhaps more importantly, the concept may also allay increasing concerns about the potential dangers of artificial intelligence without a human in the loop. A team of Naval Postgraduate researchers are currently exploring a concept of “network optional warfare” and proposing technologies to create a “mesh network” for independent SAG tactical operations with designated command and control.

…And The Connected Human

Adm. Girrier was quick to point out that the strategy – aimed primarily at enabling submarines, surface ships, and some land-based operations to take advantage of fast-emerging computer technologies — was by no means intended to replace humans. Rather, it aims to leverage human perception and cognitive ability to operate multiple drones while functioning in a command and control capacity. In the opinion of this author, a major issue to be resolved in optimizing humans and machines working together is the obstacle of “information overload” for the human.

Captain Wayne P. Hughes Jr, U.S. Navy (Ret.), a professor in the Department of Operations Research at the Naval Postgraduate School, has already noted the important trend in “scouting” (or ISR) effectiveness. In his opinion, processing information has become a greater challenge than collecting it. Thus, the emphasis must be shifted from the gathering and delivery of information to the fusion and interpretation of information. According to CAPT Hughes, “the current trend is a shift of emphasis from the means of scouting…to the fusion and interpretation of massive amounts of information into an essence on which commanders may decide and act.”

Leaders of the Surface Navy continue to lay the intellectual groundwork for Distributed Lethality – defined as a tactical shift to re-organize and re-equip the surface fleet by grouping ships into small Surface Action Groups (SAGs) and increasing their complement of anti-ship weapons. This may be an opportune time to introduce the concept of swarm intelligence for decentralized command and control. Technologies could still be developed to centralize the control of multiple SAGs designed to counter adversaries in an A2/AD environment. But swarm intelligence technologies could also be used in which small surface combatants would each act locally on local information, with systemic order “emerging” from their collective dynamics.

Conclusion

Yes, technology is going to enable increased autonomy, as noted by Adm. Girrier in his interview with Scout Warrior. But as he said, it will be critical to keep the human in the loop and to focus on optimizing how humans and machines can better work together. While noting that decisions about the use of lethal force with unmanned systems will, according to Pentagon doctrine, be made by human beings in a command and control capacity, we must be assured that global order will continue to emerge with humans in control.

Marjorie Greene is a Research Analyst with the Center for Naval Analyses. She has more than 25 years’ management experience in both government and commercial organizations and has recently specialized in finding S&T solutions for the U. S. Marine Corps. She earned a B.S. in mathematics from Creighton University, an M.A. in mathematics from the University of Nebraska, and completed her Ph.D. course work in Operations Research from The Johns Hopkins University. The views expressed here are her own.

Featured Image: An MQ-8B Fire Scout UAS is tested off the Coast Guard Cutter Bertholf near Los Angeles, Dec. 5 2014. The Coast Guard Research and Development Center has been testing UAS platforms consistently for the last three years. (U.S. Coast Guard)