Last week was a good one for Polish Navy. A few things happened which look minor if considered separately, but put together show a glimpse of how the Polish Navy will look in the future. As publicly available information about military matters in Poland is still scarce, there is also room to put these events in broader perspective and explore their philosophical underpinnings.

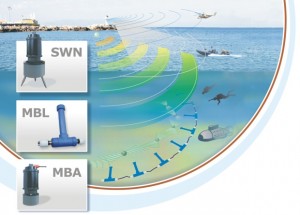

The week started with information that REMUS 100 won a tender to provide 2 systems for harbor-defense use by the naval bases in Swinoujscie and Gdynia. Later, at the Maritime Systems and Technologies 2013 Europe (MAST) conference and the NATO Naval Armaments Group meeting, both taking place in Gdansk, participants had the opportunity to see a live demonstration of Maritime Infrastructure Protection Systems, a multi-sensor maritime-monitoring system designed by CTM Gdynia. The next day, the Polish MoD issued a Request For Information (RFI) for just such a system, and, the very same day issued an RFI for patrol ships and corvettes. Little is known about these ships but the patrol ship is supposed to be in the range of 1,700 tons and possess the “capability to search and destroy naval mines and other dangerous underwater charges”. The corvette, which is officially called the Coastal Defense Ship, is expected to carry among other things weapons for “precision strike of land targets”. In parallel, the MoD prepared a tender for highly publicized project of Air and Anti-missile Defense, which will consist of 6 medium-range (100 km) and 11 short-range (25 km) batteries. Although that was not a predominantly naval development, the Navy’s modernization plan foresees 2 short-range batteries to be included in force structure. Add to that announcement the following and the overall picture becomes clearer: the newly commissioned Nadbrzezny Dywizjon Rakietowy (Coastal Defense Battery), equipped with Kongsberg NSM missiles will be extended to have a 2nd unit, there are rumors that planned submarines should be armed with “deterrence weapons”, and an ambitious plan that 3 new mine-hunters should join the fleet starting from 2016.

The first impression that comes to mind is that the protection of infrastructure and naval bases is viewed as a critical priority. This is also the message from the recently concluded mine-counter measures (MCM) exercise, IMCMEX 2013 – “It is more than just MCM”. The logic is simple – Two naval bases, one Swinoujscie and one in Gdynia, requires two sets of defensive weapons and systems. Taking a step back, the MoD seems to be building A2/AD fleet or modern version of Jeune Ecole, which is not surprising for a continentally oriented armed forces. At this point I start to have some problems with terminology in defining what kind of navy the Polish Navy will be. If we measure distance between major ports or naval bases in the Baltic Sea in a straight line we get following results:

Szczecin to Kiel, Germany: 147nm

Szczecin to Korsoer, Denmark: 139nm

Gdynia to Karlskrona, Sweden: 144nm

Gdynia to Baltijsk (In Kaliningrad, Russia): 47.5nm

This situation is not unusual in narrow waters but raises the question as to what degree we can speak about “area denial” when this area is congested, contested, and probably beyond control for anybody. In such a case the term “sea control” should have a very Corbettian meaning: “here and now”. In the extreme case of Gdynia and Baltijsk we observe a sort of direct contact within the range of modern artillery. It becomes hard to speak about any area to deny.

On the other hand if we use term Jeune Ecole, which heavily relied on torpedo boats, then another question emerges: how effective was this asymmetrical weapon of époque against an enemy battle force? Sir Julian Corbett, as Prof. James Holmes recently reminded us, was very concerned by the fact that the first torpedo-armed flotillas made fleets structureless, the weapons greatly empowering small craft and upsetting defined roles. Can we say something more on that subject after 100 years of experience? My not very scientific and brief review of Conway’s Battleships reveals that out of roughly 194 battleships constructed and commissioned (including a few completed as aircraft carriers), only three have been sunk as a result of torpedo attacks of surface flotilla ships [Scott C-P did an unscientific review last year of all types of sinkings]. These were Szent Istvan, Fuso and Yamashiro. In addition four were torpedoed and sunk by submarines, which at least at the time of Corbett’s writing were considered flotilla vessels. They were Barham, Royal Oak, Courageous, and Shinano. This produces a total of 3.6% — not much, and an invitation to reconsider the viability of a coastal navy focused on asymmetric weapons only. We need some symmetry in force structure as well.

The conceptual roots of the Polish Navy maybe lies in von Clausewitz’s thesis that defense is a stronger form of war than offense, but seeks an opportunity to switch to offense as soon as possible. Using Sir Julian Corbett’s subtitle from his “Green Pamphlet”, this Navy will seek a decision on land engaging in “offensive operations used with a defensive intention”. It leads me to my final and perhaps banal conclusion that the closer to the coast the Navy acts, the more land-warfare theories apply.

Przemek Krajewski alias Viribus Unitis is a blogger In Poland. His area of interest is broad context of purpose and structure of Navy and promoting discussions on these subjects In his country