By Andrew Orchard

The U.S. Navy’s history is rich with inspiring achievements in information warfare, from Station Hypo’s successes in World War II to supporting raids against high-value targets during the Global War on Terror. Inspiring as U.S. Naval Intelligence history has been, achieving victory in the next fight will require specific training focused on developing the skills required to cope with all the data available to today’s information warriors.

Since the end of the Cold War, the U.S. Navy has greatly expanded its data-technology and collection capacity to meet analytical needs, creating a challenging paradigm: a data glut and an information deficit. Data literacy is key to reducing the disparity.1

Data literacy centers on reading, analyzing, and communicating with data. It is not a science:2 Reading requires understanding what data is and the aspects of the world it represents. Analyzing data refers to aggregating, sorting, and converting it into useful information. Finally, communicating with data means using that data to support a logical narrative to a particular audience, and is of the utmost importance to any navy’s information warriors.3 A naval intelligence example of data literacy at work is determining adversary reconnaissance aircraft sortie schedules and maintenance days, and then effectively communicating the derived intelligence to improve and better inform the Warfare Commander’s decision space.

Operational Intelligence Center

Pressured by advances in the speed, precision, and destructive force of naval weapons, operational intelligence (OPINTEL) is critical, and empowering U.S. Naval Intelligence through data literacy may be the key. This is not a new concept. Analysts harnessed these techniques during the Cold War when Navy Ocean Surveillance Information Centers (NOSIC) developed and employed databases of prior Soviet activities to inform analyses of ongoing operations.4 These successes in data literacy facilitated a favorable Cold War OPINTEL asymmetry that proved a key advantage over the Warsaw Pact.5 Available battlespace awareness technology is already making this task easier. However, making sense of the battlespace requires more than just using automated OPINTEL applications.

Data literacy, not science or analytics, is the answer, as it provides Naval Intelligence professionals with the ability to synthesize information and further aid tactical commanders in making informed decisions. OPINTEL centers can become tailored centers of excellence through data literacy. To streamline scouting the positions of Soviet forces in the 1970s, Fleet Ocean Surveillance Information Facility (FOSIF) centralized collection, exploitation, analysis, and dissemination, as scouting is not complete until the collected information is delivered to the tactical commander. Fusing information from national and tactical sensors, FOSIF’s dedicated support provided the intelligence needed for the fleet to operate further forward resulting in more efficient scouting.6, 7, 8

What and Why … Data-Driven Decision Making

Advances in digital technology produced exponential data growth, and the private sector began to develop essential technology and skills to understand this ever-expanding resource. This development mirrored similar operations analysis and research advances during World War II. Adding data and analysis in the private sector built an innovative school of thought: data-driven decision-making, emphasizing data literacy over science.9

Data literacy is an essential component of an organization’s strong data strategy. It promotes understanding and fosters workforce incorporation of data into daily operations. Not laying such a foundation and skipping right to higher-end approaches like data science will not achieve the macro-level result of making data more useful across the entire organization. The “godfather” of data literacy, Jordan Morrow, notes: “One doesn’t go from not being a runner to racing a 50-mile ultra-marathon the next day.” 10

Instead, Morrow emphasizes the three Cs: Curiosity, Creativity, and Critical thinking. Morrow’s proven approach promotes literacy and data “democratization.”11 An entire workforce using data can lead to a more adaptive and successful organization, as highlighted by a ThoughtSpot and Harvard Business Review study. The report found that successful companies enable all employees through data literacy to make more informed decisions resulting in higher customer and employee satisfaction and higher productivity.12 This increased productivity reduces the glut and bottlenecks by enabling data use among frontline workers.

Data experts recommend a three-step framework: defining literacy goals, assessing the workforce’s current skills, and laying out a learning path.13 Naval Intelligence’s goal should be to create a confident and curious force that can critically think with data to support better and faster decisions throughout the spectrum of conflict. This simple goal focuses on people, as they matter most.

The assessment process aims to set measurable goals and lay the foundation for making Naval Intelligence more data literate. Assessing baseline data skills begins with examining how Naval Intelligence uses data in battlespace awareness, assured command and control, and integrated fires. Understanding how data is applied across the community identifies core skills and helps foster a culture that appreciates the value of data literacy.

The assessment process should also include examining data tool usage and functionality. Experts believe such analysis is crucial to improving return on investment and developing a tailored learning path that fully leverages technology. The final part of the assessment process is surveying the force by testing a sample of personnel on their ability to read, work with, analyze, and communicate with data in ways that support better warfighting.

Informed by the assessment, the data literacy-learning path will align with the Naval Intelligence training continuum. A data-literate cadre begins with exposing personnel to data during accession schools. Initial instruction will teach new personnel the value of data by introducing common concepts and language. The foundational education cultivates the three Cs by building confidence and demonstrating data’s possibilities while reducing barriers. Training will continue throughout accession and intermediate schools as personnel will receive instruction on data tools and functionality.

The learning path will not end at the schoolhouse. Each step of the Fleet Response Training Program (FRTP) will reinforce data literacy by teaching information warfare teams afloat how to use data.

The Three Cs: Applied to a Taiwan ADIZ Case

Data literacy empowers a workforce to see the world differently. Economist Tim Harford wrote: “Whatever we’re trying to understand about the world, each other, and ourselves, we won’t get far without statistics.” 14 Applying these skills to publicly available Taiwan Air Defense Identification Zone (TADIZ) data can exemplify the power of data literacy.

Since September 2020, Taiwan’s Ministry of National Defense has publicly reported on the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) air operations inside the TADIZ. The PLA flew 3158 TADIZ sorties as of 5 March 2023, likely as part of a larger effort to erode Taiwan sovereignty and message against outside interference. 15, 16, 17 This begs the question, is there an operational objective that aligns with the strategic intent?

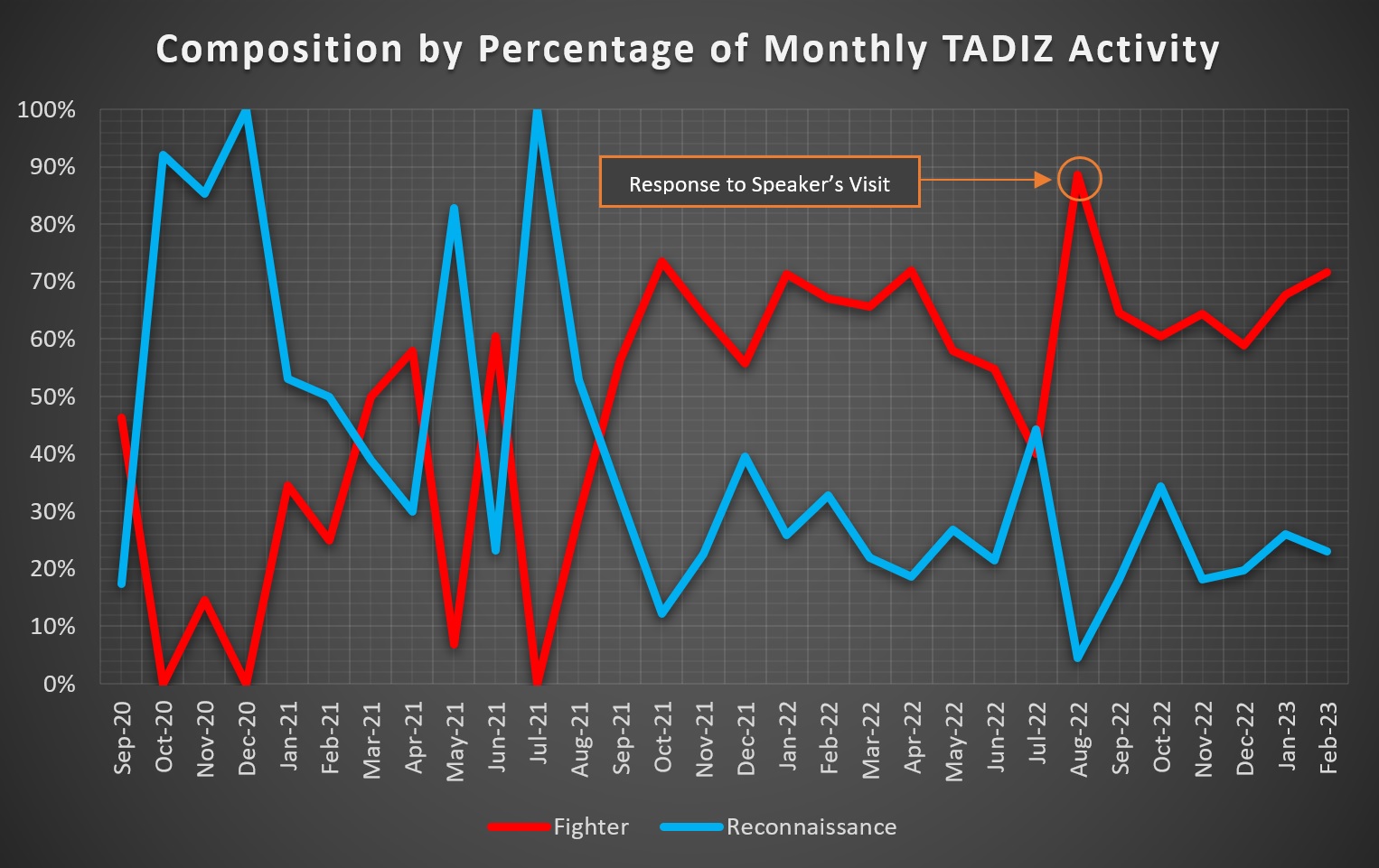

PLA aircraft reportedly entered the TADIZ on 67% of days between 9 September 2020 and 5 March 2023.18 Most (77%) of the daily incursions involved less than the mean number of aircraft (5.04), and about a third (34%) of daily incursions had only one aircraft enter the TADIZ. The majority of single sortie missions (63%) occurred between October 2020 and September 2021. Reconnaissance aircraft primarily (95%) flew these missions. Such domain awareness sorties also normalized incursions and reinforced Chinese interests while challenging Taiwan’s ability to enforce its declared ADIZ.19

These actions likely forced Taiwan to choose between either not responding to the incursions or expending finite military resources (aircraft and pilot hours), thereby achieving China’s goal of pressuring Taiwan, according to Dr. Ying Yu Lin.20 If Taiwan did not respond, the flights could be perceived as legitimizing Chinese claims and eroding those of Taiwan.

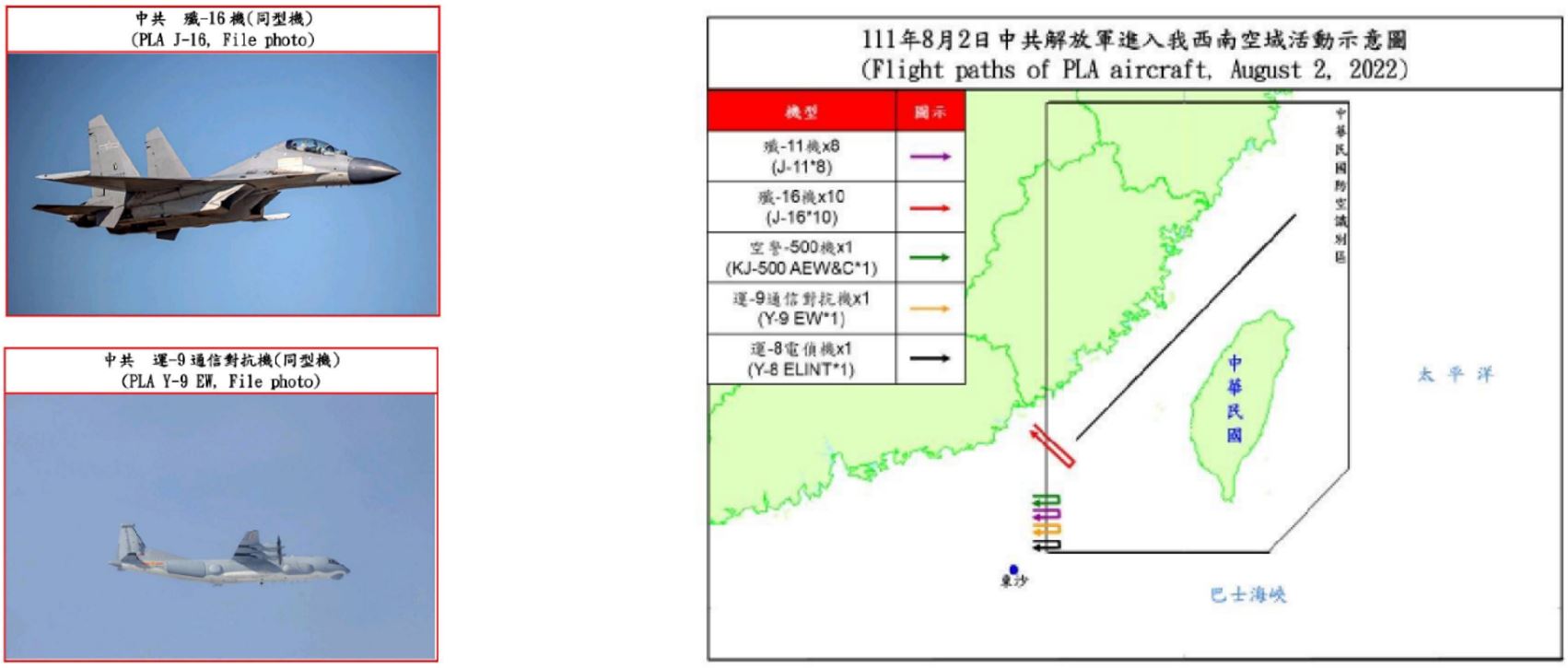

The PLA transitioned to predominantly fighter incursions (a mean of 64% of monthly TADIZ activity) in September 2021, further bolstering its claims of control over the airspace while increasing the pressure on Taiwan. Fighter sorties also accounted for an even more significant portion (89%) of TADIZ incursions in reaction to then Speaker Pelosi’s 2 August 2022 Taiwan visit.

During the month-long response to the Speaker’s visit, the PLA persistently flew a larger volume of incursions. The daily mean (15) number of aircraft throughout the response was well above the mean (11) number of aircraft flown in reaction to other international engagements with or exercises near Taiwan. Previous reactions also only lasted 1-3 days. The PLA likely increased its sorties to explicitly demonstrate airspace control and force Taiwan to expend more resources as punishment.

The Need for Data Literacy

Applying the Three Cs to recognize patterns like the transition to predominantly fighter TADIZ incursions increases operational awareness in near real-time and can support ongoing analysis similar to the NOSIC’s databases. This renewed emphasis on data can improve fleet operations by providing tactical commanders with objective facts, increasing OPINTEL support and understanding of adversary objectives.

Achieving such an OPINTEL advantage requires a data-literate U.S. Naval Intelligence community that can rapidly turn the glut into usable information. An entire force able to discover critical insights and efficiently communicate will tightly couple intelligence and analysis to the engagement of targets during distributed maritime operations. As ADM Gilday noted: “Information has become the cornerstone of how we operate.”21 Gaining favorable OPINTEL asymmetry enables the decision advantage by providing commanders with the information required to “…decide and act faster than anyone else.”22, 23, 24

Andrew Orchard is a U.S. Navy intelligence officer and selected Mansfield Fellow, currently serving as the Officer in Charge of the Joint Reserve Intelligence Center New Orleans.

The views expressed in this article is that of the author and does not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Navy, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

Endnotes

1. Sharman, CAPT Christopher. China Moves Out: Stepping Stones Toward a New Maritime Strategy. Washington D.C.: Nation Defense University, 2015.

2. Morrow, Jordan. Data Literacy – The Human Element in Data United Nations Office of Information and Communications Technology. 25 November 2020.

3. Brown, Sara. “How to Build Data Literacy in Your Company.” 9 February 2021. MIT Sloan Management School. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-to-build-data-literacy-your-company.

4. Rosenberg, Christopher Ford and David. “The Naval Intelligence Underpinnings of Reagan’s Maritime Strategy.” The Journal of Strategic Studies (2005): 397.

5. Ibid, 402.

6. Hughes, CAPT (ret) Wayne. Fleet Tactics and Coastal Combat. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 2000. 175.

7. Rosenberg, Christopher Ford and David. “The Naval Intelligence Underpinnings of Reagan’s Maritime Strategy.” The Journal of Strategic Studies (2005): 402.

8. Ball, Desmond Ball and Desmond. The Tools of Owatatsumi: Japan’s Ocean Surveillance and Coastal Defence Capabilities. Canberra: ANU Press, 2015. 93-96.

9. Stobierski, Tim. “The Advantages of Data-Driven Decision-Making.” 26 August 2021. Harvard Business Review. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/data-driven-decision-making.

10. Morrow, Jordan. Data Literacy – The Human Element in Data United Nations Office of Information and Communications Technology. 25 November 2020.

11. Morrow, Jordan. Jordan Morrow and Qlik’s Mission to Create a Data-Literate Workforce. 15 April 2020. https://medium.com/digital-bulletin/jordan-morrow-and-qliks-mission-to-create-a-data-literate-workforce-c450a01714f5.

12. ThoughtSpot and Harvard Business Review. The New Decision Makers. Cambridge: Harvard Business Review, 2020.

13. Brown, Sara. “How to Build Data Literacy in Your Company.” 9 February 2021. MIT Sloan Management School. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/how-to-build-data-literacy-your-company.

14. Harford Tim. The Data Detective: Ten Easy Rules to Make Sense of Statistics. New York: Penguin Random House, 2021. 16.

15. All TADIZ data is derived from public releases by the Taiwan Ministry of Defense. Military News Updates. 10 November 2022. https://www.mnd.gov.tw/English/PublishTable.aspx?types=Military%20News%20Update&Title=News%20Channel.

16. Kenneth Allen, Gerald Brown, and Thomas Shattuck. Assessing China’s Growing Air Incursions into Taiwan’s ADIZ Bonny Lin. 1 April 2022.

17. U-Jin, Olli Pekka Suorsa and Adrian Ang. “China’s Air Incursions Into Taiwan’s ADIZ Focus on ‘Anti-Access’ and Maritime Deterrence.” The Diplomat 20 July 2021.

18. TADIZ analysis based on publicly available data and conducted by Andrew Orchard in private capacity.

19. Silva Shih, Shuren Koo, Daniel Kao, Sylvia Lee, Yingyu Chen. “Why the Chinese Military Has Increased Activity Near Taiwan.” CommonWealth 2 November 2021.

20. Deutsche Welle. “China’s Taiwan Military Incursions Test the Limits of Airspace.” Deutsche Welle 4 October 2021.

21. Gamboa, Elisha. “CNO in San Diego, Meets with Project Overmatch Team on Fleet Modernization.” Navy.mil 23 February 2021.

22. Ibid.

23. For an additional collated form of the Taiwan Ministry of Defense publicly available data please see Gerald C. Brown’s and Ben Lewis’ google sheet. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1qbfYF0VgDBJoFZN5elpZwNTiKZ4nvCUcs5a7oYwm52g/htmlview

24. The author wishes to thank Christopher Underwood and Ryan Meder for advice on this article.

Featured Image: SOUTH CHINA SEA (Feb. 6, 2023) U.S. Navy Ensign Bradley Davis stands watch aboard the Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Wayne E. Meyer (DDG 108). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Mykala Keckeisen)