By Phillip Bass

Because wars between great powers are no longer frequent, many great powers use indirect action and soft power to push foreign policy objectives.1 Joseph S. Nye Jr. describes soft power as the ability of a state to persuade another state to do what it wants without force or coercion. Soft power can come in the form of diplomatic pressure, trade relations, investment, and loans.2 The People’s Republic of China has been using soft power in Africa, Southeast Asia, and Latin America (LA) to fulfill foreign policy objectives. Chinese soft power in LA is a potential challenge to the United States’ hemispheric dominance.3 The Monroe Doctrine and the Roosevelt Corollary showed the United States was willing to use hard power to keep great powers out of LA.4 The United States’ dominance could be challenged if Chinese investment influences LA foreign policy.5 China has used soft power to pursue its foreign policy objectives in LA to delegitimize the Republic of China (Taiwan), access LA raw resources, and provide an alternative to American investment. These moves have made China vulnerable to events in Latin America. Investment changes a state’s foreign policy if the state is the investor, or if invested states have more to gain than by pursuing an alternative avenue.

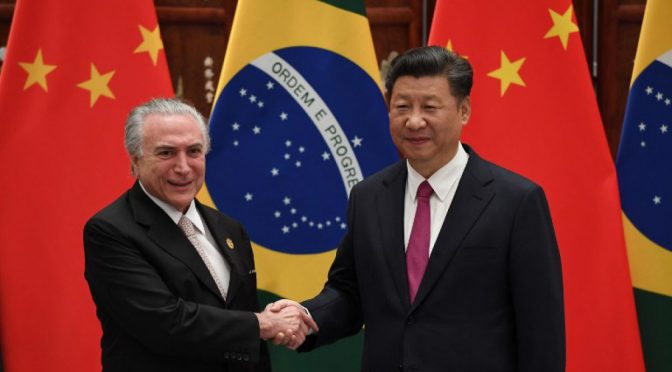

Chinese investment in LA has increased from $15 billion in 2000 to $268.7 billion in 2013.6 China has invested $116.4 billion into Brazil, Venezuela, and Ecuador from 2007 to 2016.7 China gave Venezuela $60 billion worth of loans to help the country prior through 2015.8 China formed the China-CELAC Forum to promote economic relations between China and LA.9 At its first meeting in January 2015, Chinese President, Xi Jinping pledged China would invest $500 billion into LA by 2019.10 China has signed free trade agreements with Chile, Peru, and Costa Rica.11 China is one of the top five export destinations for Argentina, Cuba, and Peru. Additionally, China is Brazil and Chile’s largest trading partner. China is also one of the top five importers for Colombia, Mexico, and Uruguay.12 With Chinese interests investing large amounts of funds and trade into LA, it is important to see if investment changes states’ foreign policy.

Chinese soft power has put pressure on Central American states to not recognize Taiwan in favor of stronger relations to China. Twelve of the twenty-one countries that recognize Taiwan are in LA.13 After Costa Rica switched diplomatic recognition from Taiwan to China in 2007, China and Costa Rica began negotiations for a free trade agreement in 2008 and the free trade agreement launched in 2011.14 In ten years, China has grown to deliver 12.6 percent of Costa Rica’s imports.15 When China-CELAC was launched, Costa Rica was asked to serve as the first chair of the Forum.16 Not every Chinese initiative has worked as well as its endeavors with Costa Rica; setbacks on the development of the $50 billion Nicaraguan Canal have disturbed bilateral relations between China and Nicaragua, where setbacks have delayed the development project from its late 2016 start date.17 In January 2017, Nicaragua’s President Daniel Ortega and Taiwan’s President Tasi Ing-wen had meetings to promote bilateral relations. Afterward, Ortega vowed to expand Taiwan’s international presence.18

Investment from China in LA focuses on the extraction of raw resources. Venezuela, Brazil, and Ecuador are the top three destinations for Chinese investment in LA. Twenty-eight of the thirty-two projects from the Chinese Development Bank in Brazil, Venezuela, and Ecuador are energy deals.19 High volumes of Chinese investment into raw resources is consistent across LA. Four-fifths of all Chinese investment in LA have been in resource extraction, with 70 percent of investment into oil and gas.20 Chinese shares of LA exports increased from 2 percent in 1993 to 9 percent in 2013.21 While China’s manufacturing imports from LA remain at 2 percent since 2003, their share of extraction and agriculture sectors has increased to 15 percent each.22 LA exports to China have also changed. From 1999-2003, oil and gas extraction consisted of 25 percent of LA exports to China. By 2013, oil and gas extraction consisted of 56 percent of LA exports to China.23

Chinese loans and investment in LA suggest they are using soft power to support countries wanting an alternative to American investment. While Brazil is less resistant to the United States’ presence in LA, Ecuador and Venezuela are both members of the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA). ALBA seeks to promote the self-determination of LA states against United States’ investment. ALBA derailed the Free Trade Area of the Americas.24 Chinese investment in ALBA members suggests that Chinese investment finances countries wanting an alternative to the United States’ investment. China has invested $62.2 billion into development projects in Venezuela; almost 48 percent of total investment in LA.25 Venezuela also accepted $60 billion dollars in loans from China prior to the current economic crisis.26 Ecuador has borrowed upward of $11 billion from China between 2008 and 2014, covering 61 percent of Ecuadorian government spending.27 While China is not directly challenging American soft power in LA, Chinese investment supports governments that desire an alternative to the United States’ dominance.

Chinese investment and desire for LA raw resources has influenced China’s foreign policy. Prior to investing into LA, China would not be involved in crises in LA, but became involved in LA domestic crises in recent years. As Venezuela’s economy continues to spiral downward, the Chinese government invited economists and opposition lawmakers from Venezuela to Beijing throughout 2016. Officials discussed the $20 billion Venezuela owes China for loans and the possibility of a transitional government to bring stability to Venezuela.28 Ultimately, China decided to invest $2.2 billion to gain more share of the Venezuelan oil economy, from 500,000 barrels a day to 800,000 barrels a day in January 2017.29 Whether for good or bad, China’s foreign policy must now react to developments in LA to protect economic interests and imports of raw resources from LA.

Chinese investment in LA shows that investment changes a state’s foreign policy if they are the investor, or if the invested state has more to gain than an alternative. China is using soft power in LA to delegitimize Taiwan, have access to new raw resources, and to provide an alternative to U.S. dominance. Some of these efforts have led to positive results for China, but there have been setbacks for China. The more China invests into these objectives in LA, the more LA crises will affect Chinese foreign policy. If this relationship is beneficial for LA countries, they will also commit more to bilateral relations with China.

Phillip Bass is a junior studying International Relations at the University of Central Florida. Phillip is the Vice President of the International Relations Club, an organization that promotes academic and professional development of international relations students. Phillip is primarily interested in European studies. Phillip is interested in moving into policy making fields or graduate school after his undergrad.

References

1. Kissinger, Henry A. 2012. “The Future of U.S.-Chinese Relations: Conflict Is a Choice, Not a Necessity.” Foreign Affairs, Vol. 91, No. 2 44-55.

2. Nye, Joseph. 1990. Bound to Lead: The Changing Nature of American Power. New York: Basic Books.

3. Kissinger. 48.

4. Coatsworth, John H. 2017. United States Interventions. March 20. http://revista.drclas.harvard.edu/book/united-states-interventions

5. Committee on Foreign Affairs: House of Representatives. 2015. “China’s Advance in Latin America and the Caribbean.” 2.

6. Committee on Foreign Affairs: House of Representatives. 2.

7. “The Dialogue”. 2016. China-Latin America Finance Database. March 25. http://www.thedialogue.org/map_list/.

8. Vyas, Kejal. 2016. China Rethinks Its Alliance With Reeling Venezuela. September 11. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rethinks-its-alliance-with-reeling-venezuela-1473628506?mg=id-wsj.

9. China-CELAC Forum. 2014. About the Forum. Accessed March 27, 2017. http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/.

10. Jinping, Xi H.E. 2015. “Jointly Write a New Chapter in the Partnership of Comprehensive Cooperation Between China and Latin America and the Caribbean.” Embassy of the People’s Republic of China in the United States of America. January 8. http://www.china-embassy.org/eng/zgyw/t1227730.htm.

11. Chinese Ministry of Commerce. 2015. November 18. http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/english/index.shtml.

12. United Nations. UNcomtrade Analytics. Accessed March 27, 2017. https://comtrade.un.org/labs/data-explorer/.

13. Ministry of Foreign Affairs for the Republic of China. 2017. Diplomatic Allies. March 24. http://www.mofa.gov.tw/en/AlliesIndex.aspx?n=DF6F8F246049F8D6&sms=A76B7230ADF29736.

14. Chinese Ministry of Commerce. 2015. November 18. http://fta.mofcom.gov.cn/english/index.shtml.

15. World Trade Organization. 2017. Costa Rica. March 20. http://stat.wto.org/CountryProfiles/CR_e.htm.

16. China-CELAC Forum. 2014. About the Forum. Accessed March 27, 2017. http://www.chinacelacforum.org/eng/.

17. Watts, Jonathan. 2016. Nicaragua canal: in a sleepy Pacific port, something stirs. November 24. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/nov/24/nicaragua-canal-interoceanic-preparations.

18. Pretel, Enrique Andres. 2017. Nicaragua pledges to fight for Taiwan recognition on global stage. January 11. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-taiwan-usa-nicaragua-idUSKBN14V03Z?il=0.

19. The Dialogue. 2016. China-Latin America Finance Database. March 25. http://www.thedialogue.org/map_list/.

20. Gallagher, Kevin P, Lopez Andres, Rebecca Ray, and Cynthia Sanborn. 2015. “China in Latin America: Lessons for South-South Cooperation and Sustainable Development.” Global Economic Governance Initiative 6.

21. Gallagher et al. 5.

22. Gallagher et al. 5.

23. Gallagher et al. 5.

24. ALBA. 2017. What is the ALBA? March 25. https://albainfo.org/what-is-the-alba/.

25. “The Dialogue”.

26. Vyas, Kejal. 2016. China Rethinks Its Alliance With Reeling Venezuela. September 11. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rethinks-its-alliance-with-reeling-venezuela-1473628506?mg=id-wsj.

27. Kuo, Lily. 2014. Ecuador’s unhealthy dependence on China is about to get $1.5 billion worse. August 27. https://qz.com/256925/ecuadors-unhealthy-dependence-on-china-is-about-to-get-1-5-billion-worse/.

28. Vyas. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rethinks-its-alliance-with-reeling-venezuela-1473628506?mg=id-wsj.

29. Vyas. https://www.wsj.com/articles/china-rethinks-its-alliance-with-reeling-venezuela-1473628506?mg=id-wsj.

Featured image: Chinese President Xi Jinping (R) shakes hands with Brazil’s President Michel Temer during their meeting at the West lake State Guest House in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province, China, September 2, 2016 (Minor Iwasaki/Reuters).

America’s maritime security picture as well. The region’s naval and coast guard forces are modernizing accordingly to meet these challenges and opportunities.

America’s maritime security picture as well. The region’s naval and coast guard forces are modernizing accordingly to meet these challenges and opportunities.