Alternative Naval Force Structure Topic Week

By Steve Wills

Navies have historically sought alternative force structures in response to changes in their nation’s grand strategy, rising costs of maintaining existing force structure, advances in technology, and combinations of these conditions. While initially appealing in terms of meeting new strategic needs, saving money, and gaining offensive and defensive superiority over an opponent, such changes are fraught with danger if undertaken too quickly, are too radical in tone, or do not account for the possibility of further change. Some are built “from the bottom up” on ideal tactical combat conditions, but do not support wider strategic needs. Even the best alternative force structure that meets strategic needs, is more affordable than previous capabilities, and outguns the enemy could be subject to obsolescence before most of its units are launched. These case studies in alternative force structure suggest that such efforts are often less than successful in application.

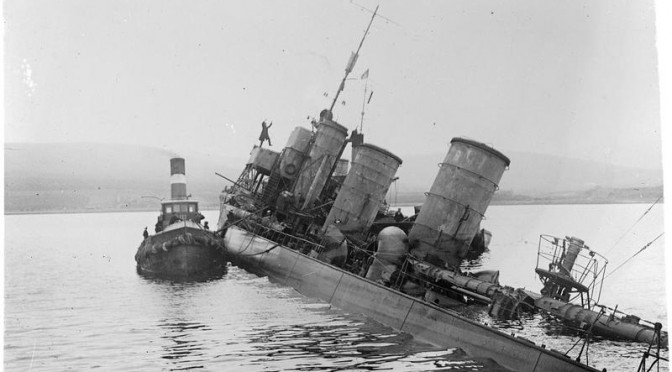

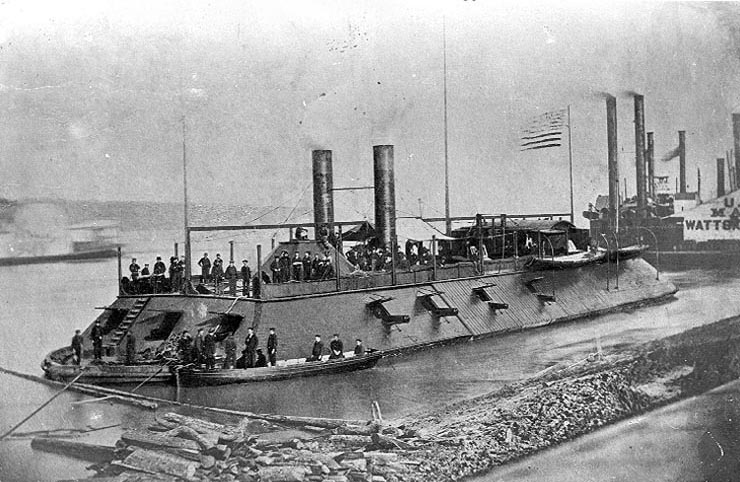

The American Civil War Ironclads

One of the most familiar alternative force structures was that of the United States Navy in response to the revolutions in steam power, armor, and rifled cannon in the late 1850s. The impending appearance of the rebel warship CSS Virginia (the former steam frigate USS Merrimac) during the American Civil War triggered a crash course in ironclad warship experimentation in the Federal Navy. When Virginia did appear, the only one of these experiments ready for battle was Swedish engineer John Ericsson’s USS Monitor, a revolutionary craft in comparison to both the Federal fleet’s current force structure and other experimental craft. The success of Ericsson’s craft against the Virginia spawned over 60 other low freeboard armored vessels with one, two, and even three turrets. Despite several losses, including that of the namesake ship, to weather conditions, and one (USS Tecumseh) to a torpedo (mine) hit, the monitor type ships had a remarkable record of combat success in coastal and riverine environments during the Civil War.

Unfortunately, the return of peace and the need to maintain overseas naval squadrons to protect U.S. economic interests spelled an end to the dominance of the monitor in U.S. naval force structure. One conducted a high-profile overseas visit to Europe while a second managed to sail around Cape Horn only to be immediately decommissioned upon arrival in San Francisco. Monitor-type ships had poor seakeeping capabilities outside coastal waters and did not carry enough coal for extended operations. The U.S. had not developed the high-freeboard sail and steam warships that other powers had constructed, and in any case U.S. strategic interests had changed to where monitors were no longer necessary components of naval force structure. Nearly all were decommissioned and scrapped or laid up in long-term reserve by 1874.

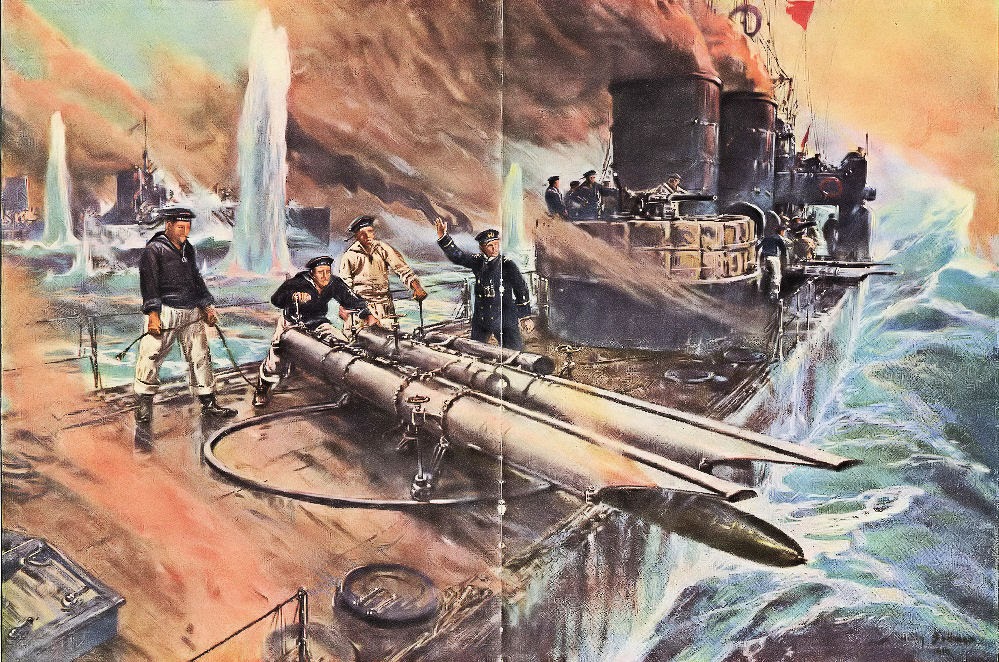

The “Jeune Ecole” (Young School) Torpedo Craft and Commerce Raiders

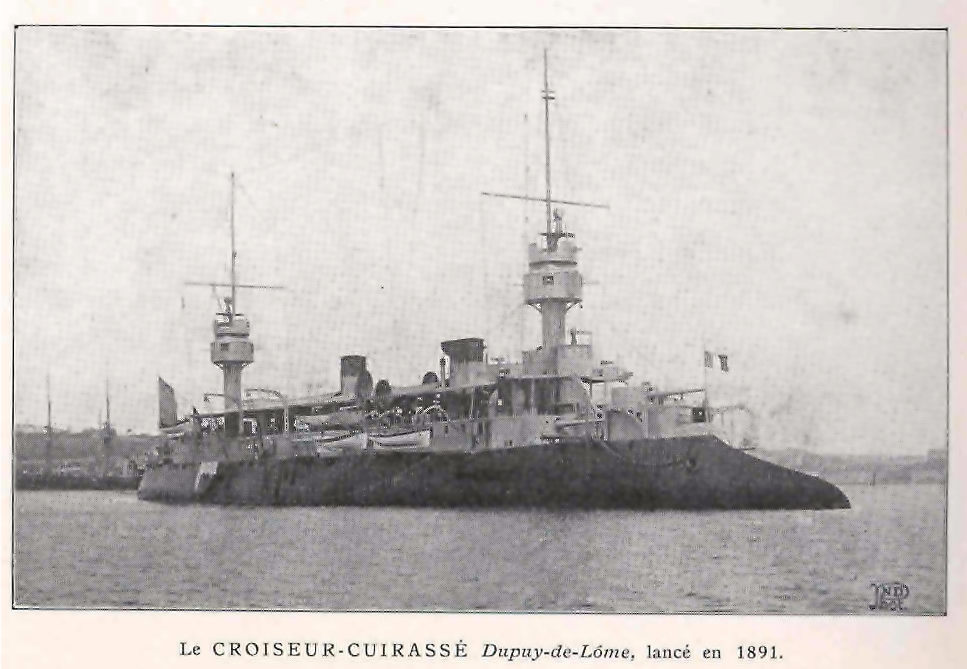

The “Jeune Ecole” (Young School) of French naval strategy was the brainchild of Vice Admiral Hyacinthe-Laurent-Theophile Aube and developed in the mid to late 19th century in response to the growing battleship fleet of France’s primary adversary, Great Britain. Rather than build a competing battlefleet, French strategists derived an alternative force structure designed to offset British battleship superiority and attack a perceived weakness in Britain’s global maritime trade network. French designers planned for masses of small, torpedo-armed craft to launch large salvos of underwater weapons at the exposed, unarmored lower sides of British battleships. Torpedo craft were much cheaper and easier to build in numbers as opposed to battleships. They also had a successful combat record with spar-mounted weapons in the American Civil War, and later successes in the Russo-Turkish War, South American conflicts, and in the Russo-Japanese War.

Commerce raiding conducted by fast cruisers, as conduced by rebel naval forces during the American Civil War, was also seen as an asymmetric tool for combating global maritime powers with vulnerable trade routes. Defending naval forces could not be everywhere and took time to assemble in areas threatened by a surface raider.

Unfortunately, the march of technological advance that supported the tenets of the Jeune Ecole also served to undermine them. Nations whose battleships were threatened by torpedo boats developed the larger and more capable torpedo boat destroyer to escort their battleships, destroy enemy torpedo boats, and launch their own torpedo attacks against opposing forces. Advances in battleship gunnery in the first decade of the 20th century allowed capital ships to open fire at ranges greater than that of the torpedo, making daylight attacks suicidal for torpedo craft.

Surface commerce raiding also ran up against new technologies that made it largely ineffective. First, undersea communication cables and later radio allowed for long-range communication between naval leaders at home and their forces deployed around the world. Commerce raiders that had to stop to take on coal and provisions would have their locations reported much more rapidly than in past centuries, allowing naval forces to concentrate and destroy them. Radio intercepts also allowed pursuing forces to track surface raiders. British naval forces quickly identified and eliminated German cruiser formations engaged in commerce raiding once radio communications reported their positions. Raiders disguised as merchant ships persisted into the Second World War, but submarines that could submerge and operate undetected became much more effective commerce raiders.

The Jeune Ecole was also in effect a tactical concept elevated to the rank of strategy. While torpedo attacks might sink British battleships attacking French coastal waters and commerce raiders might weaken British commerce, how did the force structure promote French strategic goals? How would these formations protect France’s own far-flung possessions; a colonial amalgamate that was second in size only to that of Great Britain’s? How would lightly armed and armored commerce raiders and generally unseaworthy torpedo boats carry the fight to British shores if needed? The Jeune Ecole did not answer these questions of strategic employment of French naval forces.

France also reached a political settlement with Great Britain in the early 20th century and the French fleet of raiding cruisers and torpedo boats was left without an enemy. France would likely have benefited from a more balanced fleet in the First World War and struggled to catch up in the dreadnought building race that commenced shortly after its “Entente Cordiale” agreement with Great Britain.

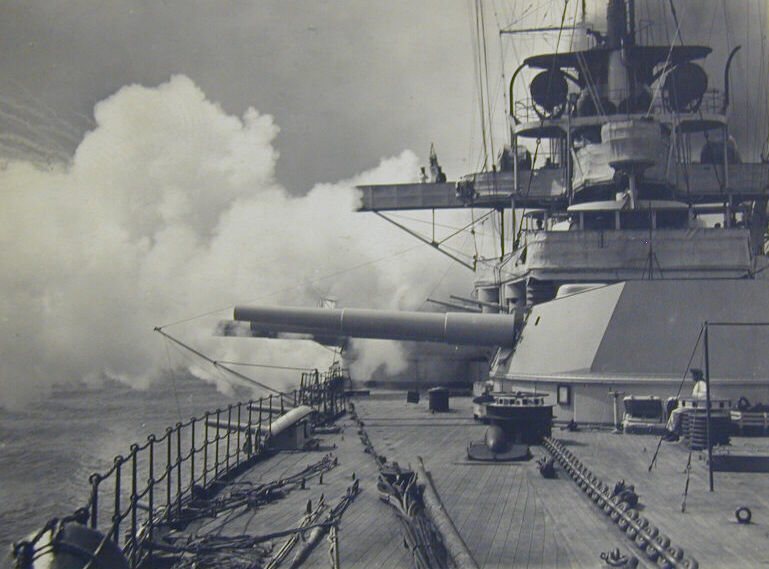

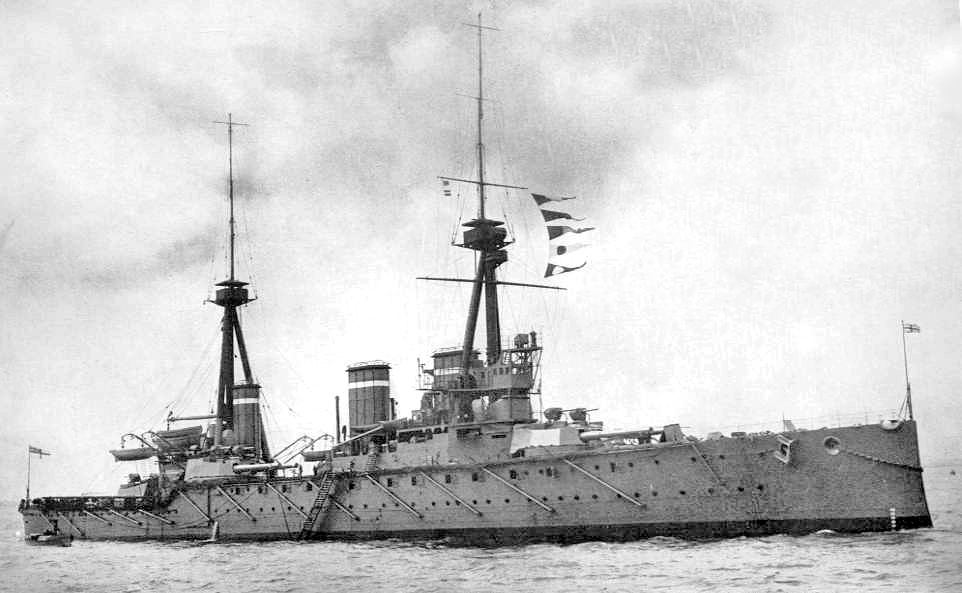

Jackie Fisher’s Fleet

Great Britain experimented with its own alternative fleet force structure at the outset of the 20th century. This was the “fleet that Jack built;” the pre-World War 1 fleet of battlecruisers, large destroyers, submarines, and other revolutionary warships that sprang from the fertile mind of British Admiral Sir John Fisher. The fiery Fisher, who in U.S. service might have resembled a combination of Admirals Hyman G. Rickover and Arthur Cebrowski, was selected to be First Sea Lord (British equivalent of the U.S. Chief of Naval Operations) in 1904 with a mandate to cut costs and increase combat capability. Fisher’s answer to this problem partially involved a revolutionary new force structure of hybrid ships that combined existing classes in order to meet British strategic needs while lowering naval estimates. The battlecruiser that combined the firepower of a battleship with the speed and range of armored cruiser would speed to threatened areas of the globe and destroy slower, less well-armed enemies at long range. Defense of the United Kingdom itself would be left to torpedo-armed large destroyers and submarines. Fisher was a strong advocate of new technologies and supported naval aviation, steam powered-submarines, director firing of warship guns, and cleaner, more efficient oil fuel for warships in place of coal.

Despite being innovative and well connected to British grand strategy, Fisher’s fleet was largely obsolete in less than ten years. Britain’s primary enemy changed from France and its Jeune Ecole-based trade warfare fleet to Germany that built a similar fleet of battleships and battlecruisers for operations in European waters. Apparently, Fisher never expected anyone to create a mirror image of his battlecruiser fleet. Fisher’s big ships were instead assigned as heavy scouts for a British fleet expecting a fleet battle in the close confines of the North Sea.

Technology also advanced beyond Fisher’s initial concepts. The fast battleship, which carried heavy guns, was well armored and had a decent turn of speed obviated the need for the specialized battlecruisers. Fisher’s steam-powered submarines were ahead of their time, but plagued by technological issues that limited their effectiveness. The German surface fleet only made rare appearances and Germany’s merchant fleet was largely interned or destroyed by the end of the first year of war, leaving few targets for Fisher’s submersibles. The Battle of Jutland, the one great naval encounter of the war, did not offer proof that Fisher’s force structure was right or wrong. Instead, poor tactical doctrine (not a lack of armor) caused significant casualties among Fisher’s battlecruisers. The less than satisfactory results left the Royal Navy with a haunting experience of frustration and regret that would not be extirpated until the Second World War. He was out of power and office by 1916 due to his repeated clashes with his protégé Winston Churchill over the conduct of the Dardanelles campaign. Fisher’s revolution achieved much for the Royal Navy in its first five years, but was effectively over after the first two years of the First World War.

Zumwalt’s High/Low Mix

Finally, there is the 1970s era U.S. Navy attempt at an alternative force structure launched by revolutionary Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Elmo Zumwalt Jr. Like Fisher who faced reduced naval estimates due to the costs of the unpopular Boer War and a rising welfare state, Zumwalt also had to contend with a U.S. naval budget limited by the expenditures for the Vietnam War and for President Johnson’s social welfare programs. In response, Zumwalt conceived of a high/low concept for U.S. naval force structure where, in the words of retired naval officer and Hoover Institute scholar Captain Paul Ryan, “A few high-performance ships and many low-performance ones would avoid wrecking the budget but not expose the nation to risks represented by large emerging fleets of small, fast, cruise missile-armed combatants.”

Zumwalt’s program included reduced funding for large, nuclear aircraft carriers and guided missile escorts, but greater support for a number of low-end vessels including the Sea Control Ship, the patrol frigate (which later became the FFG 7 Perry class frigate), and the Pegasus class hydrofoil combatant. Zumwalt intended that the low-end ships would operate in support of general sea control in low threat areas rather than focus on the Navy’s power projection concept developed after the Second World War.

Zumwalt’s program found favor with those in Congress who were happy to spend less on the fleet, but met stiff opposition from within the Navy’s own ranks, especially from carrier aviators unhappy with reduced investment in carriers. Strategy-minded individuals also opposed the high/low force structure as they felt it failed to appreciate the Navy’s vital, carrier-based strike capability as the real war winning capability fielded by the fleet. Naval historian Norman Friedman, for example, labeled high/low as, “An un-Mahanian excursion,” and former 6th Fleet Commander Vice Admiral Gerald E. Miller remarked that, “the Sea Control ship might deny the Soviets access to the Chesapeake Bay,” but that its effective use ended there.

Zumwalt’s low-end ships had faults of their own that were difficult to overcome. In addition to the operational limitations of the Sea Control Ship, the patrol frigate (Perry) class went from a $50 million dollar combatant to an average cost of $193 million dollars by the end of the 51-ship program. The patrol hydrofoils were short-ranged and were focused more toward offensive action than the peacetime patrol and presence operations the Navy required. Estimates on their operating costs vary, but only 6 of the intended 30 were completed with Zumwalt’s successors.

Changes in the strategic situation confronting the U.S. across the 1970s served to bring the high/low alternative force structure to an end by 1980. Intelligence gathered from taps on Soviet Navy underwater communications cables suggested the USSR was not planning a 3rd Battle of the Atlantic where Zumwalt’s force would have been most useful. The Communist superpower instead intended to keep its submarines close to the homeland to protect its ballistic missile submarines and attack U.S. carriers threatening Soviet bases. Response to this plan called for more high-end warships such as large aircraft carriers and their escorts. While ultimately not successful, Zumwalt’s efforts did lead to better armament for U.S. Navy surface ships such as the Harpoon missile.

Modern Parallels

These case studies suggest that alternative force structures are born from a desire to achieve strategic advantage over an opponent, take advantage of technological advances, and save costs in the execution of strategic policy. Current proposals for alternative force structures follow similar pathways. Concepts for arming a new generation of warships with directed energy weapons and railguns, thereby capturing the high ground of advanced technology, are similar to the U.S. Navy’s monitor program of the Civil War. Like the monitors of the 1860s, current designs for railgun and directed energy weapons are in their infancy but potentially very powerful. Initial versions will be expensive and likely to be rapidly outmoded by technological advance.

Proposals for large fleets of smaller, more expendable warships that can be built at low cost mirror the French Jeune Ecole. Those same proposals are also an attempt to build a strategic plan from a tactical or operational concept.

Hybrid warships that combine the capabilities of multiple ships on a common hull, like the U.S. littoral combat ship (LCS) are reminiscent of John Fisher’s battlecruisers. Fisher’s later entrants into the battlecruiser category later found gainful employment in the Second World War as refitted fast capital ships or as aircraft carriers. The long-term success of the LCS may also depend on its ability to adapt to new missions.

Alternative force structures can also meet challenges from within their host navies. Admiral Zumwalt’s high/low mix faced considerable opposition from carrier aviators within the U.S. Navy hierarchy. The low costs with Zumwalt’s low-end ships were much greater than first estimated and the strategic situation changed as in past cases making the alternative force structure much less attractive. The U.S. LCS design, conceived as a low- end combatant in a period of lower threats and fiscal austerity, faces similar challenges in ensuring relevance in a new period of Cold War-like peer/near peer competition. Unlike the late 1970s, there is little chance of a Reagan-like defense budget in the immediate U.S. future. Sequestration budget caps are likely to continue, dimming the chances of a higher-end surface combatant to replace the LCS.

Conclusion

Alternative force structures offer the promise of harnessing new technology, overcoming a specific opponent platform, and cost savings in defense procurement. Naval leaders should be wary in their adoption. Periods of rapid technology as those that occurred in the second half of the 19th century and those occurring in the present can rapidly condemn today’s alternative force to an early reserve fleet or scrapyard. High costs incurred in the construction and fielding of a rapidly obsolete alternative force are not easily recouped. Alternative forces inspired by tactical requirements may find themselves at odds with current and future strategies. Finally, even the best alternative force crafted to meet current strategic requirements can be reduced to irrelevance with the stroke of a pen in a diplomatic agreement. Historically, balanced fleets of mixed capabilities have fared better in naval battles and maintained relevance through evolving threat environments. Navies should consider all of these points before embarking on the perilous quest for the perfect alternative force structure.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.

Featured Image: The USS Zumwalt sits at dock at the naval station in Newport, R.I., Friday, Sept. 9, 2016. (AP Photo/Michael Dwyer)