Some historians attempt to reframe the timeline of history in order to highlight trends that might otherwise remain submerged in more traditional categories. The British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawn, for example, re-classified the long period from the French Revolution to the beginning of the First World War as the “long” 19th century. This change showcased a particular period of European ascendency through the Napoleonic, Revolutionary, Victorian and Edwardian periods. A similar effort might now be applied to the influence of the U.S. Army on United States strategic thinking. A “Long Army Century” is now drawing to a close due to new strategic geography and shrinking defense budgets.

The “long Army century” arguably began in 1904 with the selection of New York corporate lawyer Elihu Root as the Secretary of the Army by President William McKinley in 1899. While the U.S. Army had been victorious in Cuba in the Spanish American War, its organization, operations, and logistics during that conflict revealed deep flaws that might circumscribe future success. Root undertook an aggressive program that created the modern Army General Staff, the Army War College, and the Joint Army Navy board for inter-service cooperation.

The Chief of Staff system, modeled on methods then used by American business, was a great success. Root’s reforms created the “modern” Army that was able to mobilize large numbers of volunteers for the First World War. This system eagerly embraced new technologies such as the tank and the airplane, and was successful in deploying millions of Americans to fight in France in a relatively short time. The Army also had great influence over large numbers of civilians for the first time since the Civil War, as high ranking Army leaders served in key roles on the War Industries Board that coordinated U.S. war production.

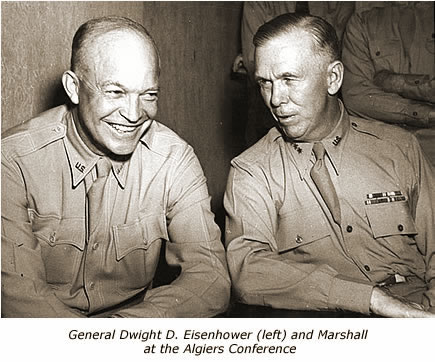

The end of the First World War brought a reduction in overall Army influence, but future influential leaders including George C. Marshall, Dwight D. Eisenhower, George Patton and many others were direct products of Root’s post-1903 reforms. These leaders fought the Second World War, and others again occupied significant roles in civilian government like General Leslie Groves who managed the Manhattan Project. The end of World War 2 should have brought about another reduction in Army strength and influence, but the emerging Cold War and the strong personalities of Marshall, Eisenhower, and other products of the Root Army War College had other ideas.

The Army targeted the Navy as unfairly hoarding resources in a “parochial” manner in order to gain its share of scarce financial resources at the beginning of the Cold War. One of the best ways to do this was to advocate for a unified “joint” military force with relatively co-equal branches under a supreme “generalissimo” of the U.S. armed forces. This is not surprising given the wartime experience of the post World War 2 U.S. Army leadership. Officers such as Marshall, Eisenhower, and Omar Bradley served primarily in the wartime European theater of operations where land and air warfare were the predominant modes of fighting. The “Battle of the Atlantic” against the German U-boat arm never fell under Eisenhower’s direct supervision. He and other Army officers respected the ability of naval forces to mount the Normandy invasion, but had little or no direct experience with naval combat. Postwar naval leaders such as Chester Nimitz, Forrest Sherman, and Arleigh Burke by contrast had experienced a relatively decentralized war in the Pacific. Nimitz and Army general Douglas MacArthur shared command authority and responsibility in a collaborative manner unlike the Army Chief of Staff system with one overall commander. As a result of this difference in leadership style and the fierce competition with the Navy and later the Air Force for funding, the Army enthusiastically adopted concepts of “joint” organization and control of the armed forces throughout the Cold War. Dwight Eisenhower as President tried to implement joint concepts of organization for the Department of Defense as a result of his war experience, but was thwarted in his efforts by key pro-Navy Congressional leaders.

The long and unsuccessful Vietnam War and end of the military draft in 1973 should have brought about a reduction in Army strength and influence, but the Army was again able to avoid large cuts by shifting to an all-volunteer force and refocusing on the European threat posed by the Soviet Union. Army leadership continued to advocate “joint” leadership of the U.S. Armed Forces in pursuit of desired force structure. The passage of the Goldwater Nichols Act of 1986 further cemented “joint” aspects of U.S. military strategy, policy and operations. The Gulf War of 1991 seemed to confirm that “joint” organization was crucial to U.S. military success. Building on triumph in that conflict, the Army was able to secure a significant force structure in the negotiations that produced the post-Cold War “base force” in 1994. The looming specter of a revanchist Russia, desire to enable a “New World Order”, as well as the continuing specter of Saddam Hussein’s armed forces convinced many decision-makers that there was continued value in a large expeditionary ground force. The Army found further relevance after the terrorist attacks of 9/11 and the subsequent ground invasions and counterinsurgency operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The Army’s success on the battlefield in the last 100 years, especially in more recent “joint” operations has been largely enabled by favorable geography. Combat in and around the Eurasian landmass in both World Wars, the Korean and Vietnam conflicts, and recent wars in the Persian Gulf and Southwest Asia all featured airfields within short range of hostile targets and an emphasis on the effects of land-based operations. The geography of future conflict however would seem to be shifting to largely maritime and air struggles in the Indo-Pacific basin. This region’s large maritime spaces offer few immediate venues for employment of land power as did the plains of Europe, the deserts of the Middle East and the highlands of the Hindu Kush in Afghanistan. The Air Force and Navy, rather than the Army, have the central role in Pacific strategy. The shrinking U.S. defense budget in response to national debt, trade deficits and massive new social welfare spending also works against the maintenance of continued Army force structure and influence. Without a defined mission in an essentially air and maritime battlespace, the Army has resorted to a kind of “me too” strategy advocating its ability to support the other services Pacific efforts through coastal defense, which ironically was one of the U.S. Army’s first missions in the new republic.

The Pacific Ocean, and the lands touched by its waves have always been of U.S. strategic interest. For the first time however since 1941 there is no comparable “land-based” strategic theater in competition with the Indo-Pacific region. The U.S. Army will likely have other expeditionary missions and conflicts in its future, and may again return to a level strategic influence like that it has possessed in the last 100 years. For the moment however, historians might be well served to give the present “Long Army Century” an endpoint in the early second decade of the 21st century.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD student in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941. He posts here at CIMSEC, sailorbob.com and at informationdissemination.org under the pen name of “Lazarus”.