Written by Dave Lyle for our Innovation Week.

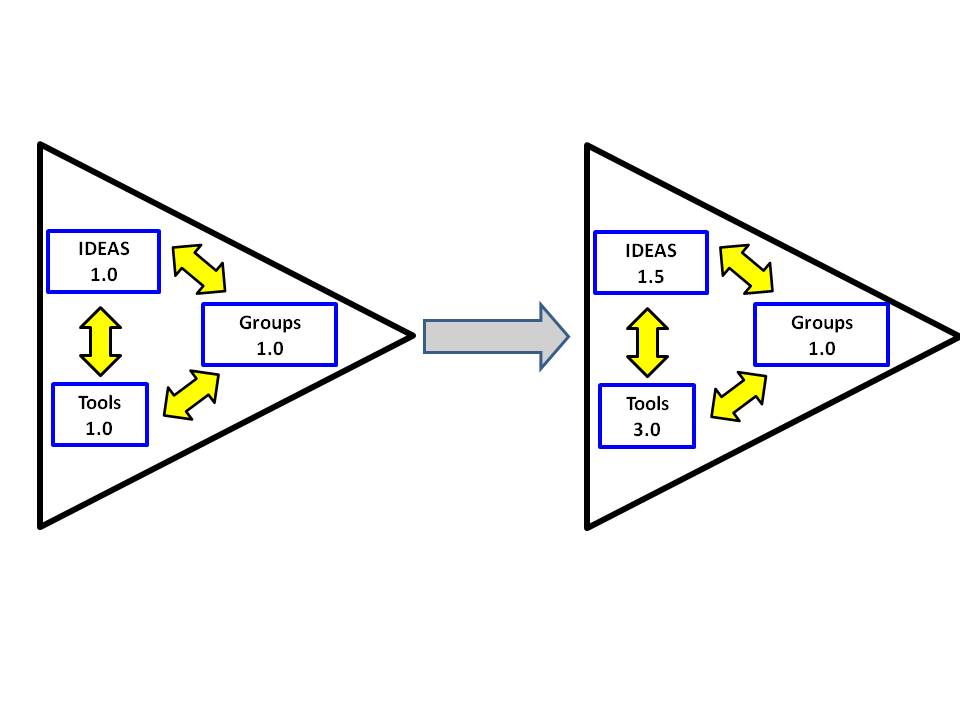

Innovation starts with ideas – the realization that something new is possible once old things are seen in new ways. Thus, it’s very important to understand how knowledge and insight are created both individually and in groups if one wishes to posture themselves to encourage successful innovations.

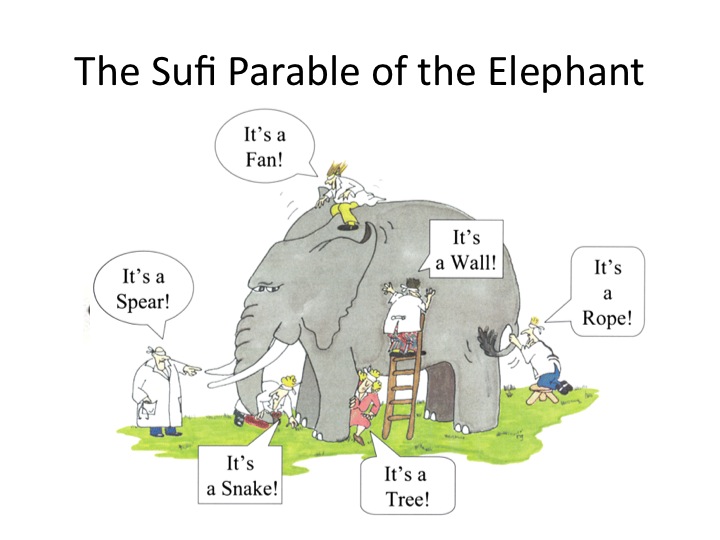

In the American Civil War, veterans used to describe their initial baptism of fire as “seeing the elephant”. But if you’re interested in the nature of innovation, there’s another elephant that you need to see before you do anything else.

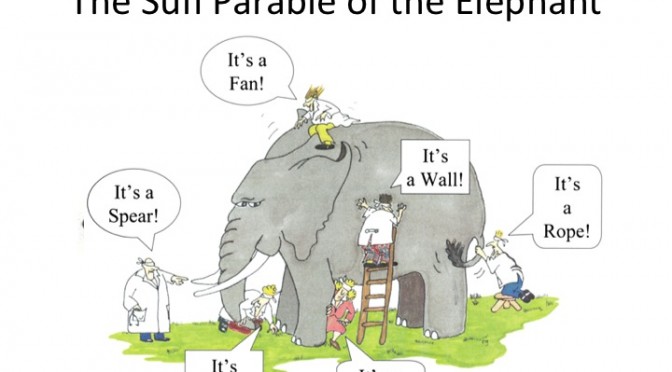

An ancient Sufi parable, the story of the blind studying an elephant reveals three tremendously important insights about how we know what we think we know:

- Our ability to observe and sense the greater environment that affects our lives is inherently limited by our own ability to perceive it, and by the limited perspectives of those we communicate with

- We get a better sense of reality by seeking multiple frames of reference to study the same problem, even if that process of “sensemaking” is still inevitably incomplete, and

- We all have a basic human tendency to assume that our limited knowledge of the world is more descriptive of the whole than it really is, and that our limited knowledge is adequate for the problem we’re trying to solve, whether it is indeed sufficient or not.

These insights hold true at both the individual level and in the sense of groups. Individually, what we perceive to be our conscious thought is really a churn of multiple, mostly unconscious mental submodels, each coming from different frames of sensory reference, and each competing for dominance of the really small portion of our total cognitive bandwith that we call conscious thought. What we perceive to be conscious choices are often driven by intuitive, gut feel actions unexplainable in specific cause and effect terms even by the people making the decision, a point Thomas Schelling made in his classic book Micromotives and Macrobehavior. From a group perspective, we have established bodies of knowledge from different perspectives, and seek to combine and reconcile these perspectives in patterns of social interaction that tend to solidify some ideas as commonly accepted frameworks of accumulated knowledge – what we commonly describe as paradigms, taking a cue from Thomas Kuhn in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.

But it’s far more complicated than that. In fact, most of the time, the elephant is constantly changing, in part due to responses to our own efforts to sense and describe it. And much of the time – like in the case of inherently unquantifiable social phenomenon like popularity, confidence, and a feeling of security – the elephant only exists as an abstract concept in our heads.

Ideas are networks

As Steven Johnson points out in his book Where Good Ideas Come From: The Natural History of Innovation, Ideas are literally networks of accumulated information encoded and continually modified in the physical and chemical structures of our brains, with collections of ideas working together as the schema we use to make sense of what our senses are detecting. In a group sense, ideas are embedded in our social conventions like our stories, norms, rules, procedures, etc .. Innovation happens when old ideas are combined in new and interesting ways, either through deliberate effort, unconscious deliberation, or through serendipitous revelation and discovery.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NugRZGDbPFU

The “slow hunch” unconscious deliberative processes that Johnson describes is reflective of the “collision of smaller hunches” that take place in the individual mind as people take collections of existing ideas, and use their intuitive, creative processes to recombine them in new , interesting, and useful ways. This mostly unconscious and intuitive creative process was described in part by Isaac Asimov as “the Eureka Phenomenon”:

http://newviewoptions.com/The-Eureka-Phenomenon-by-Isaac-Asimov.pdf

…and also by Joseph Campbell when he answered the following to Bill Moyers during the interviews that led to a modern humanities classic, The Power of Myth:

BILL MOYERS: Do you ever have the sense of… being helped by hidden hands?

JOSEPH CAMPBELL: All the time. It is miraculous. I even have a superstition that has grown on me as a result of invisible hands coming all the time – namely, that if you do follow your bliss you put yourself on a kind of track that has been there all the while, waiting for you, and the life that you ought to be living is the one you are living. When you can see that, you begin to meet people who are in your field of bliss, and they open doors to you. I say, follow your bliss and don’t be afraid, and doors will open where you didn’t know they were going to be.

http://www.jcf.org/new/index.php?categoryid=31

Combining Asimov and Campbell’s observations with a growing body of evidence from cognitive neuroscience, it seems that there really is something to “finding your calling”. Each of us have natural tendencies to be interested in specific things, and when we find the ability to concentrate on them, our drive and enthusiasm – our bliss – pushes mostly unconscious creative processes to seek creative recombinations of ideas that we’re interested in, even when we’re not consciously thinking about them.

But it’s not just about brilliant individuals bringing innovative ideas to the rest of us. The history of innovation also shows that in-person social interactions – and most importantly, serendipitous chance meetings between people who think differently – are crucial to innovation. It’s usually not the people in your own peer group who have the missing piece of a puzzle that you’re working on, because they tend to see the world much like you do. More often, it’s the people who see your problem from a completely different frame of reference that serve as the catalysts for innovative collaborations. A notable example of this was the genesis of the Doolittle Raid during World War II, when a submariner initially thought of the idea of putting US Army bombers on US Navy aircraft carriers to strike back at the Empire of Japan after the attack at Pearl Harbor, an idea that might never have occurred to Army pilots or Naval aviators who were comfortable with their own paradigms regarding what bombers and aircraft carriers could do.

http://www.uss-hornet.org/history/wwii/doolittle_bio-Francis_S_Low.shtml

Sometimes, interdisciplinary collaborations help you create new innovations even before you’ve imagined the problem. See Steven Johnson’s story of the invention of GPS at the end of this clip for a great illustration of this:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0af00UcTO-c

Thus, it’s likely no accident that many Nobel Prize winners were not specialists in the fields that they won their awards in. Being outsiders, they were free of the cognitive blinders that “dyed in the wool” specialists often accumulate. More significantly, they were free of the cognitive attachments that are created when specific ideas become associated with individual and group identities, ones that convince us that challenges to those ideas equate to being personal attacks upon ourselves. Everytime we make an idea part of our resume, our job title, or a badge on our uniform, we risk creating cognitive biases that can inhibit innovation.

Designing for Innovation

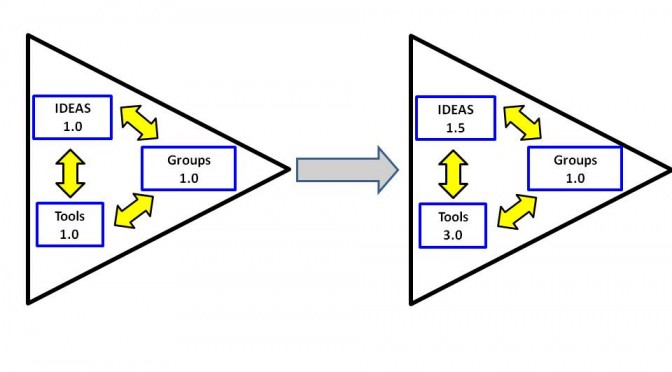

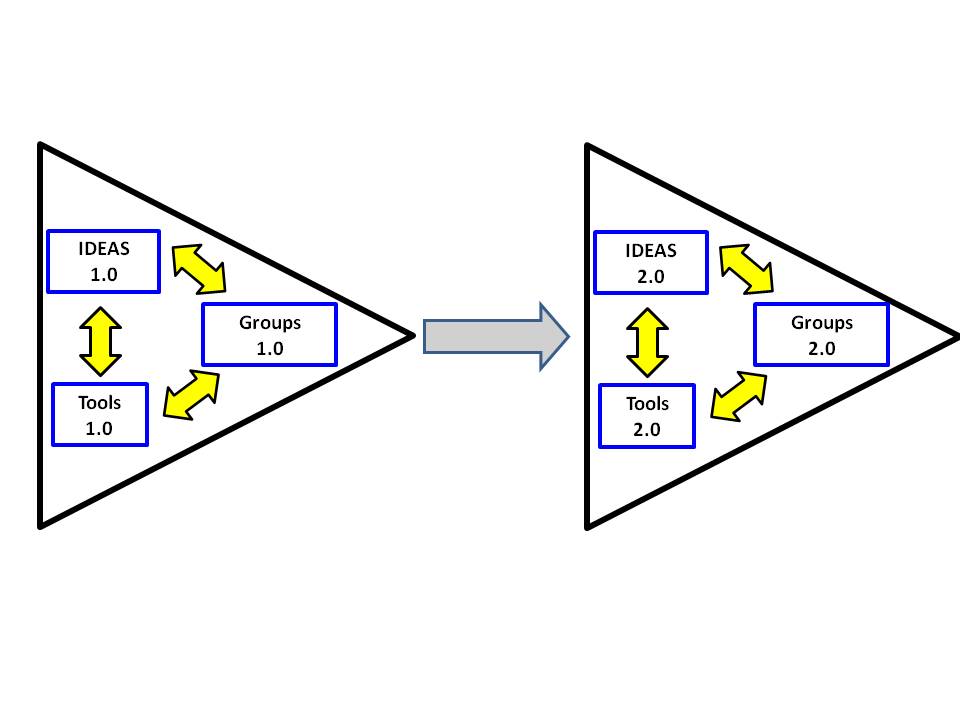

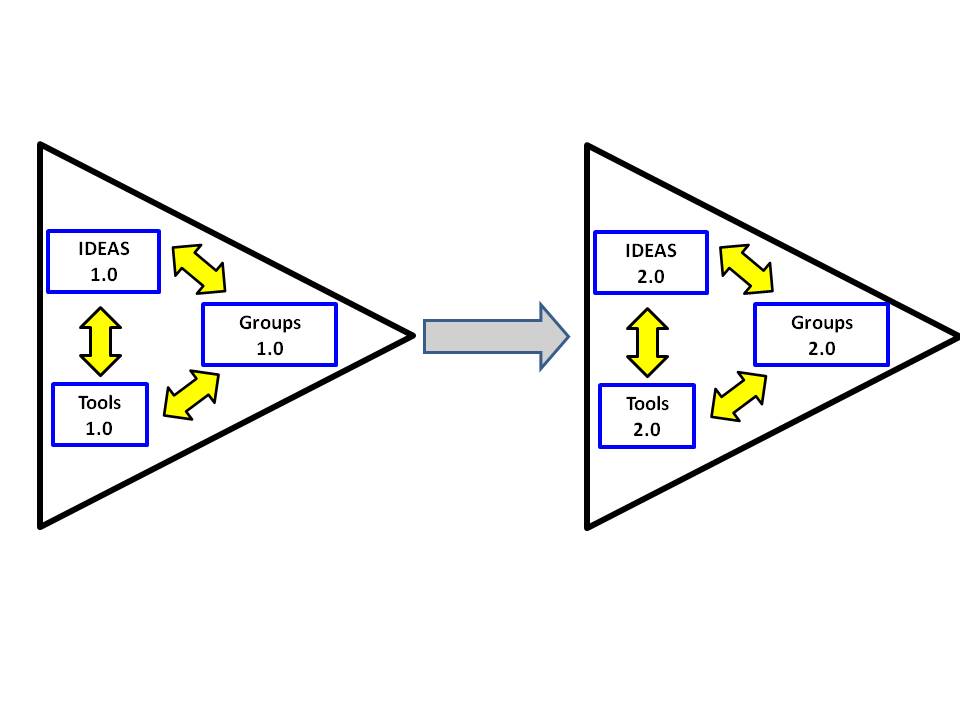

Although it took some time – and whether it was through conscious understanding of the dynamics of creativity or not – the US Department of Defense eventually created an organizational structure well suited to foster innovation though its “joint but separate” service construct. Having separate services allows creative innovation in niche areas by people who are passionate about them, and promotes resilience by preventing groupthink and “common contagions” that would be more prevalent in a single “purple” service. But by also requiring mandatory collaboration across the services as per the Goldwater Nichols act, common interoperability of both ideas and tools is promoted across the services, preventing recidivism into the dysfunctions that would result from individual services thinking only within their own specialized domains, irrespective of their contribution to the dynamic whole.

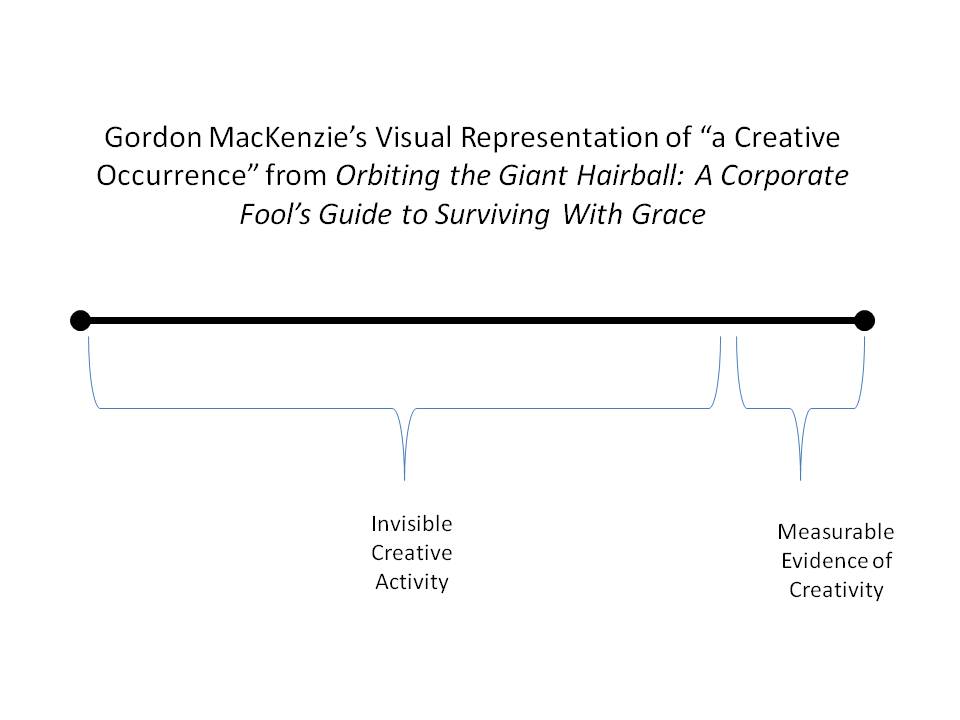

Supporting creative cross domain integration – in either the macro or micro sense – requires supervisors who can look outside of their own areas of expertise and local imperatives, and who are willing to allow their creative subordinates to do the same, in order to create greater systemic resilience across the entire force. When one is looking for innovative solutions to thorny problems, the process of coming up with those ideas is neither highly linear nor highly visible, and may require interdisciplinary, person-to-person creative explorations outside of the local norms that those who are not innovation minded will not intuitively grasp, especially when they do not match up with the normal office schedule and practices. As Gordon MacKenzie describes it in his book Orbiting the Giant Hairball: A Corporate Fool’s Guide to Surviving With Grace, a visual depiction of creative processes might look like this:

This speaks to the importance of protecting creative individuals, and the creative processes that sustain innovation, within an organization that may not understand creative people and processes very well, and may seek to minimize or expel those who it doesn’t understand that their creative process is still being “part of the team”, even if it doesn’t look at all like their daily repetitive ones. As General Mattis recently expressed it:

“Take the mavericks in your service,” he tells new officers, “the ones that wear rumpled uniforms and look like a bag of mud but whose ideas are so offsetting that they actually upset the people in the bureaucracy. One of your primary jobs is to take the risk and protect these people, because if they are not nurtured in your service, the enemy will bring their contrary ideas to you.”

http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/top_right/2011/08/gen_james_mattis_usmc.html

Conclusion

As Johnson concludes, “Chance favors the connected mind”, and this applies in both in the individual and group senses. The keys to innovation are creative exploration driven by passion, having sufficient room to play with ideas in both the conscious and unconscious sense, and in finding new way to use different parts of the individual and collective brain to look at old problems, which can be assisted by the use of visual metaphor, abstract thought experiments, and the utilization of “boundary objects” and “bridging metaphors” to create interdisciplinary dialogue that will breed innovative recombinations of previously existing ideas. By nature of its design, DEF is embracing and furthering these concepts. When it comes to sustaining innovation, it’s not just about spreading individual ideas – it’s about forming enduring networks of idea creators and enablers if you want to create vibrant and adaptive military forces who embrace change, and can rapidly respond to challenges faster than the enemy can present new ones.

Finally, Williamson Murray hammers home the need to deliberately design the ideas behind the innovation into the way we educate and develop our military leaders, and the culture that they will promote in the active force on the other side of military education.

One needs to rethink professional military education in fundamental ways. A significant portion of successful innovation in the interwar period depended on close relationships between schools of professional military education and the world of operations…[A]ny approach to military education that encourages changes in cultural values and fosters intellectual curiosity would demand more than a better school system: it demands that professional military education remain a central concern throughout the entire career of an officer. One may not create another Dowding and manage his career to the top ranks, but one can foster a military culture where those promoted to the highest ranks possess the imagination and intellectual framework to support innovation [and adaptation].

Next in the series: We’ll continue exploring the model of innovation, continuing with Groups.