On Thursday evening CIMSEC held the first annual Forum for Authors and Readers (#CFAR15). The opening keynote talk was delivered by BJ Armstrong, a member of the Center as well as a PhD Candidate in War Studies with King’s College, London and a member of the Editorial Board of the U.S. Naval Institute. The talk is based on his new book “21st Century Sims: Innovation, Education, and Leadership for the Modern Era” and kicked off an evening of great thinking and discussion on maritime affairs. We will have videos of the presentations on the website shortly. The following are his prepared remarks…

The Thinking Professional v. The Practical Officer:

Sims on Sailors, Scholars & Scribes

In November of 1900 Lieutenant William Sims joined the wardroom of USS Kentucky, the U.S. Navy’s newest battleship. He had just come from a tour in the Paris embassy, studying and collecting intelligence on European battleship design and gunnery practices. As Kentucky sailed for China Station Sims got his sea legs back and began getting to know his new ship. He started comparing what he had observed in Europe with what he found back at sea with his shipmates, and he began to think that despite new ships and a new found place on the world stage following the victory in the Spanish-American War, the U.S. Navy still had a lot of room for improvement.

In November of 1900 Lieutenant William Sims joined the wardroom of USS Kentucky, the U.S. Navy’s newest battleship. He had just come from a tour in the Paris embassy, studying and collecting intelligence on European battleship design and gunnery practices. As Kentucky sailed for China Station Sims got his sea legs back and began getting to know his new ship. He started comparing what he had observed in Europe with what he found back at sea with his shipmates, and he began to think that despite new ships and a new found place on the world stage following the victory in the Spanish-American War, the U.S. Navy still had a lot of room for improvement.

Many of you know the history that follows, how Sims found and frankly stole the concept of continuous-aim fire from Captain Percy Scott of the Royal Navy, and then went on to revolutionize naval gunnery. His course was treacherous, and unclear, but eventually throughout the fleet William Sims became known as “the man who taught us how to shoot.”

Sims continued pushing boundaries in the years leading up to World War I: advocating for the all-big-gun battleship, developing torpedo boat and destroyer tactics, and eventually commanding all American naval forces in Europe when the U.S. entered the war. During the war he was central to the adoption of the convoy system that beat the U-boats in the First Battle of the Atlantic. When he returned home he had a second term as President of the Naval War College. There he helped establish the system of study and war-gaming used in the inter-war years to develop naval aviation and American submarines.

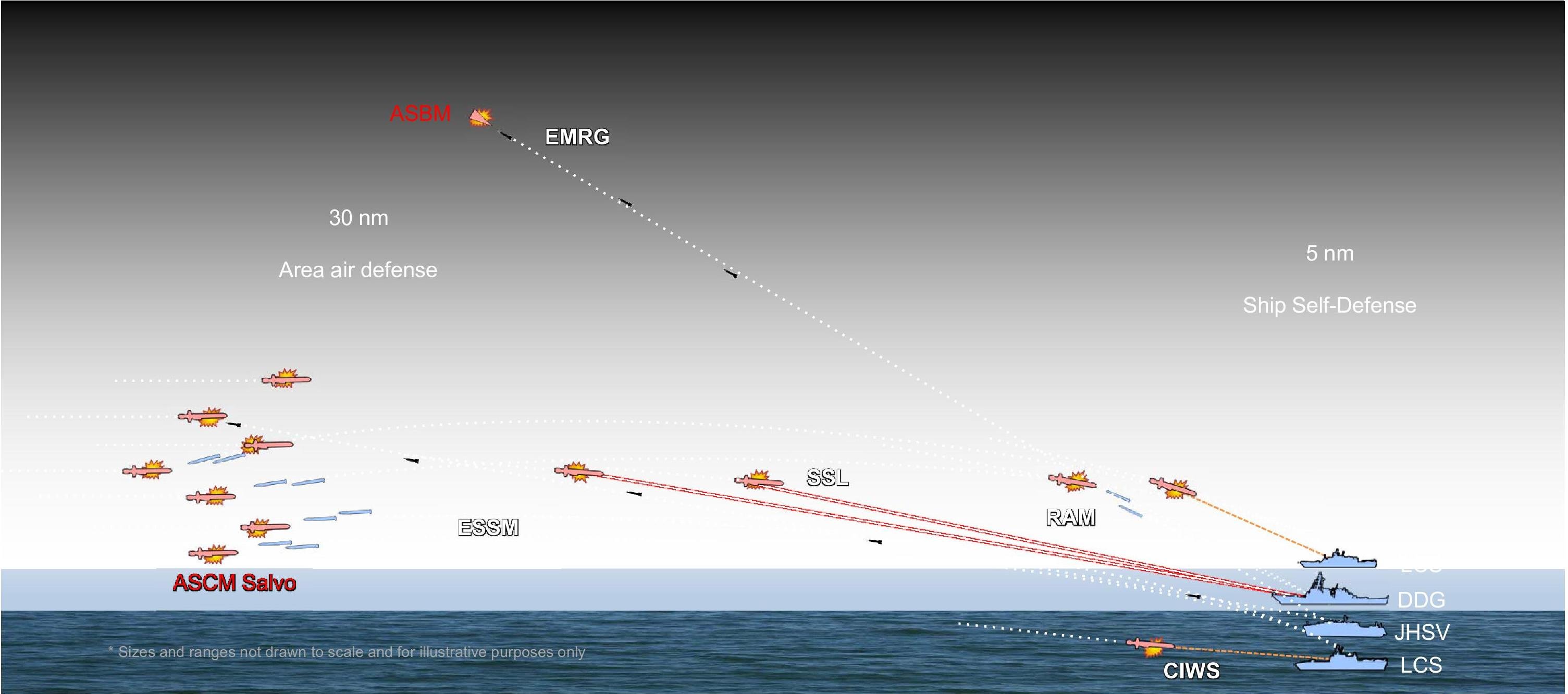

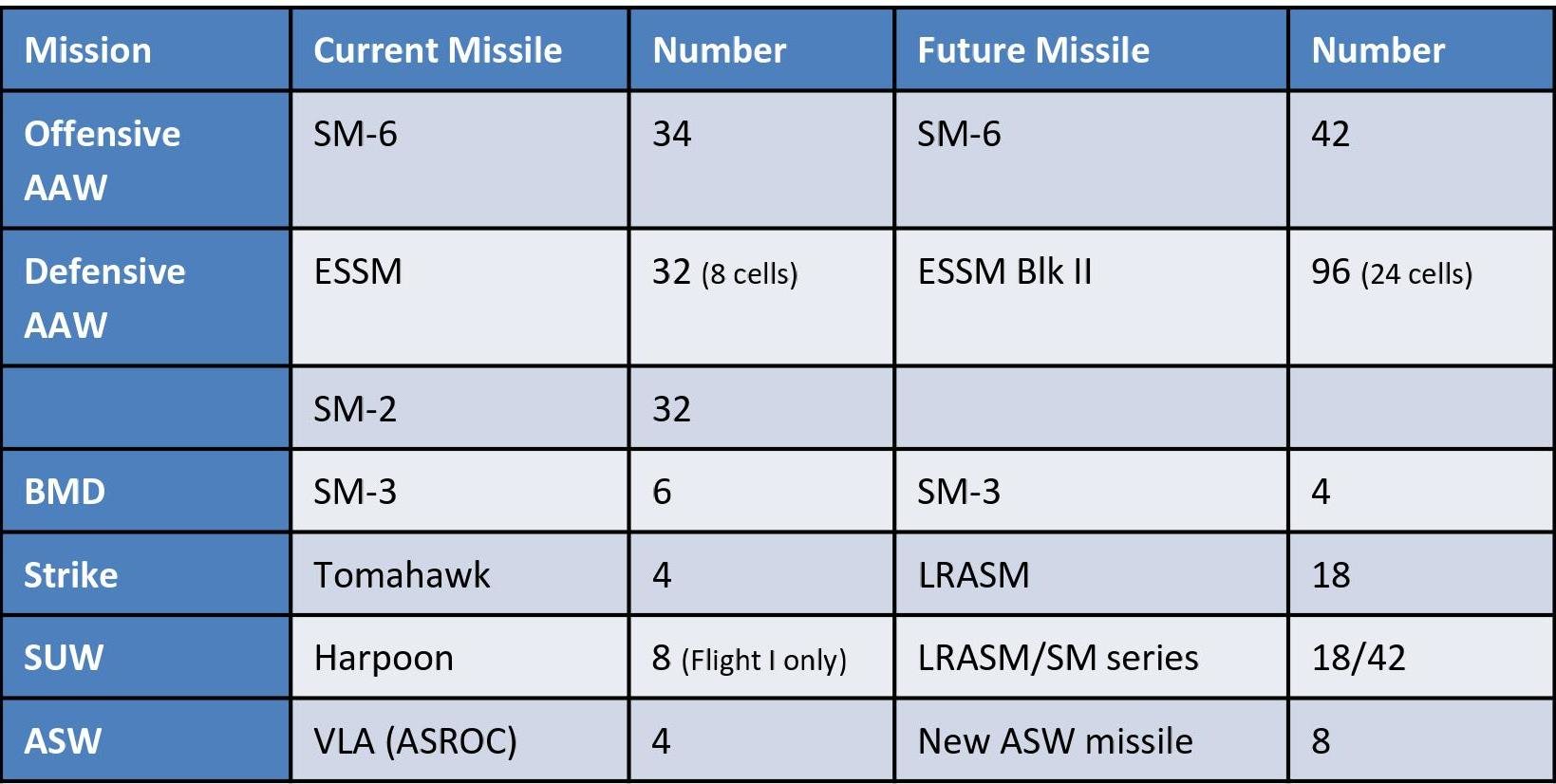

William Sims was, beyond a doubt, an innovator. Naval innovation is often seen through the lens of technology, defined by the weapons and hardware which we label as “game-changers” or “transformations.” However, some of the most important developments in history have come from the “software”: or innovations in tactics, techniques, and procedures. Like the development of continuous-aim fire. Ideas, it must be remembered, can be even more powerful than the steel and explosives that dominate our naval heritage.

It was on the prompting of President Teddy Roosevelt that Sims wrote his first article for publication. The success of that piece led him to realize the power of sharing ideas and innovations through professional writing. Throughout the remainder of his life he wrote about dozen articles for the Naval Institute’s journal Proceedings, and more for other magazines. After returning from World War I, he collaborated with Burton Hendrick to write a book. The Victory at Sea was part history and part memoir of the war, and was published to great acclaim. It won the Pulitzer Prize in 1921.

As the President of the Naval War College at the beginning of the inter-war years, Sims’ thinking on naval warfare and military professionalism had an impact on an entire generation of officers. These were men returning from war and trying to put their experience in perspective and learn lessons for the future. They had names like Nimitz, Spruance, and Halsey.

Today, the ranks of the United States military are again filled with a generation of men and women who are looking back on wartime experience. Many of our junior officers and enlisted have had a level of responsibility during their service which now causes them to bristle at perceived micromanagement and bureaucracy. The military will likely struggle over the next several years to learn how to return to non-combat roles.

What can we do to improve that struggle? What can we do today to ensure that lessons we have learned over the past decade and a half of conflict are not forgotten, and are not ignored?

Over the course of his career, Sims learned a great deal about fighting the military bureaucracy, about successful innovation, and about service before and after war. He wrote about all of these subjects in the latter part of his career, and this knowledge and advice has sat quietly in the archives for today’s innovators and service members, if they want to learn from it.

Here, with CIMSEC’s members and readers, the most relevant parts of this advice may be the importance of professional writing and personal, professional learning. Sims wrote about his experience with both. They were also central to what he saw as lacking in many officers in the Navy of his day.

Taking on The Mahan…

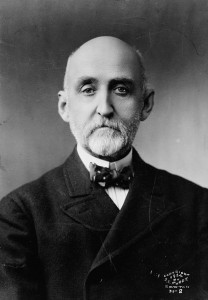

In 1906 William Sims was a Lieutenant Commander and still serving in his role as Inspector of Target Practice. The Russo-Japanese War had just come to an end, and navalists all over the world were combing through news reports and the stories of the Battle of Tsushima to analyze lessons for modern naval warfare. One of these navalists was the historian and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan.

In 1906 William Sims was a Lieutenant Commander and still serving in his role as Inspector of Target Practice. The Russo-Japanese War had just come to an end, and navalists all over the world were combing through news reports and the stories of the Battle of Tsushima to analyze lessons for modern naval warfare. One of these navalists was the historian and strategist Alfred Thayer Mahan.

In his day, Mahan was the great thinker on the subject of war and peace, something like how men like Brzezinski or Scrowcroft are seen today combined with a Stavridis or McMaster. He wrote an article for Proceedings that analyzed the events in the Sea of Japan. It drew the lesson that a properly designed fleet required battleships of moderate size, with a varied battery of different sized guns, that could be built in large numbers and were multi-mission. It was a conclusion well in line with the thinking of most of the Admirals in the Navy, and it encouraged the status quo.

Sims’ own experience, gathering intelligence on battleships and in developing continuous-aim fire, suggested something entirely different. He also had a friend with a report on the actual events in the Tsushima Strait to base his analysis on. Sims wrote an article that directly contradicted the great navalist. He demonstrated that the lesson of the Russo-Japanese War was that large battleships, with a battery full of all big guns of the same caliber, were the best way to construct a fleet, even if the expense meant you could only build a smaller number of them. As he wrote in the conclusion of his article:

“I have attempted to show that Captain Mahan’s conclusions are probably in error.”

As the development of the British Dreadnaught would demonstrate, Sims was far closer to how the navies of the world would develop than Mahan was.

Sims’ essay offers readers in the twenty-first century something more than an interesting story of two great naval minds and an abandoned ship class. First, it demonstrates how important a healthy professional debate is for our national security. Without discussion generated by forward-thinking officers and junior civilian analysts in military and security journals, both in print and today online, the military bureaucracy will stagnate and become reactionary. Without the engagement of innovative junior members of the team any organization, whether military or civilian, risks becoming followers instead of leaders in their field.

Sims’ article also demonstrates the importance of expertise. Readers will understand his deep knowledge and obvious study of battleship employment and design. Today’s military innovators and thinkers must learn from this example. They must be willing to jump into the arena of ideas, but they also must be willing to do the hard work of researching and studying their subject in order to get it right.

Today, whether the debate is about the future of the big-deck nuclear aircraft carriers as we recently saw in Annapolis, or about questions of the military effectiveness of swarming small combatants versus today’s modern dreadnaughts, the arguments must be logical, informed by a mastery of the facts, and well presented.

Sims knew that in order to engage the world’s leading navalist in a debate, in order to challenge the great Alfred Thayer Mahan, he had to have his details right and his logic had to be sound. This kind of rigorous and researched engagement on the defense questions of the day offers us an example for the twenty-first century, one that we must aspire to no matter where we are writing, whether in the pages of print journals like Proceedings or online at leading blogs like CIMSEC’s Next War or our other friends at The Strategy Bridge.

“The opportunity that can never return”

But how do we get that level of expertise? Some of it will come from our personal experience on the deckplates or in cockpits deployed across the seven seas. Or service in the desert, or working on staffs in the halls of power, or the buildings of DC. Some of it will come from studying for our tactics quizzes or our NATOPS exams in the ready rooms, or working on getting the right font on the briefing slides at a think tank. But those sources are only going to provide us with a small scale of knowledge, a vital foundation that we must master but something in desperate need of context and broadening. According to Sims we must add to that knowledge through a dedicated pursuit of personal professional study.

In 1921 Sims published his Newport lecture “The Practical Naval Officer” in Proceedings. The lecture is something like a Jazz cover, since he took the title and some of the inspiration from a lecture that Mahan had given in Newport nearly thirty years before. Sims, who had locked horns with the great navalist on Tsushima, now came to embrace his view of strategic education and how to prepare officers for the highest responsibilities of command and policy. There is much to talk about in his lecture, but I will focus on this last of his three pillars of strategic education.

Sims lamented the fact that when he was a junior officer, he spent his time reading subjects that had no real bearing on the military profession. He read some philosophy and political economy, but he appears to have avoided reading military history or learning about governments and international relations or current events. As he became more senior, he slowly realized that he was missing a lot of knowledge. In fact his own perception of his time as a student at the Naval War College wasn’t that it taught him the things he needed to know, instead it highlighted all of the things he didn’t know and still needed to learn.

He wrote:

Specifically addressing the younger officers of the navy, let me say that you now have the opportunity that can never return. It lies with you to determine whether, when you become old, you will have to regret the wasted years of your youth; whether at that period of life you will find yourselves simply “practical men”—“beefeaters’’—or really educated military naval officers.

It will depend largely upon self-instruction and self-discipline. But you must keep clearly in view the fact that, under modern naval conditions, an officer may be highly successful, and even brilliant, in all grades up to the responsible positions of high command, and then find his mind almost wholly unprepared to perform its vitally important functions in time of war.

Where to start? Well, Sims leaves us with a short reading list in his lecture, which you can find in my book “21st Century Sims.” It is impressive how well this list still stands up today. But as he points out, that is just a start. Even after completing their studies at the War College he emphasized to the graduating officers that they should consider themselves to be at the beginning of their education. They must continue on their own if they hope to achieve the level of professionalism that the American people deserve from their armed forces.

There is a common bit of advice that many of us have heard from senior officers looking to mentor us: Take care of your job today, do it well, and you will be prepared for your next job. Focus on today’s tasks and everything else will take care of itself. Sims comes out in direct opposition to this advice. Sure, from a purely careerist point of view it is the best way to ensure you have the right grades and catch phrases on your fitness report for promotion. But from a professional point of view the unspoken part of this advice is that you don’t need to look to the future, to think about the questions “above your pay grade.” Instead, once you’ve completed your daily tasks and your administrative minutia, you can just return to managing your fantasy football team or play some more video games. Even in his day Sims was incensed that senior officers continued to give this advice. He believed that professionalism was more than the shine on your shoes, or the grade on your rules of the road quiz, it meant reading and studying your profession, even in your personal time.

Summation

In his recent book “Saltwater Leadership,” which you will hear some more about later this evening, Admiral Robert Wray conducted a survey of active duty naval officers. They were asked to rank seventy six leadership traits. The last two traits on the list, the least important things to teach young naval officers about leadership, were sensitivity and scholarship. Now, a bit higher on that list was writing ability, at number 33. This begs the question, if we haven’t studied our profession or looked at it in a comprehensive and scholarly way, what exactly do we have to write about? Admiral Sims would probably take exception to this list of what today’s officers believe. He would emphasize that professional writing must be about something, it must demonstrate mastery not only of the technical aspects of a problem but also understanding of the context and history of the issues involved. It must be the result of research, personal study, and yes, scholarship.

In conclusion today, I leave you with the knowledge that the pursuit of professional writing and personal professional study has a long history in the maritime service. It is true, there appear to be very few members of the Flag Ranks who published in the pages of Proceedings before they became important enough to have a staff to help them write. But across time the sailors that really made a difference like Samuel Du Pont, William Sims, Ernest King, Chester Nimitz, Bull Halsey, Bud Zumwalt, Tom Hayward, Jim Stavridis, and a few in uniform today, studied their profession and wrote articles to forward its development. They engaged in the professional debate and discussion well before they assumed the highest responsibilities of command, and our navy and our nation are better for it.

William Sims’ writings offers us an opportunity to be mentored by an accomplished leader who lived more than a century ago. His essays and lectures, with their examples of innovation, education, and leadership, can help us look at the challenges militaries and organizations face in the twenty-first century, ask the right questions, and find solutions. These certainly apply to those in uniform, but at their heart they apply to all leaders, whether from the military, industry, or government. Everyone who is interested in thinking about defense issues.

Like Alfred Thayer Mahan before him, the foundation of much of Sims’ writing and thinking is the idea that asking questions, and doing the work of research and reflection necessary to find the right questions, is at the heart of being a professional. I hope that with new organizations like CIMSEC, and older ones like the Naval Institute, with engaged junior officers and members of the defense community, we can carry on that vital part of our naval heritage.

Thank You.