By Joseph LaFave

The U.S. Navy got a lot of press in 2017, and a lot of it was negative. In the Pacific, there were two incidents where U.S. Navy ships collided with civilian vessels, and as a result 17 American Sailors lost their lives. In the wake of these incidents, report after report has come out detailing how the U.S. Navy’s surface fleet is overworked and overwhelmed.

After the collisions, several U.S. Navy commanders lost their jobs, and charges were filed against five Navy officers for offenses ranging up to negligent homicide. This is an almost unprecedented move, and the Navy is attempting to both satisfy the public outcry and remedy the training and readiness shortfalls that have plagued the surface warfare community for some time.

The point isn’t to shame Navy leadership, but rather to point out that the Navy’s surface fleet is terribly overworked. As a nation we are asking them to do too much. Reports show that while underway, Sailors typically work 18-hour days, and fatigue has been cited as a major factor in the collisions. While there may be a desire to generate more overall mine warfare capacity, it is unrealistic to expect the rest of the surface fleet to assume any additional burden for this mission area.

The surface fleet needs to refocus its training and resources on warfighting and lethality. Of all of its currently assigned missions, mine warfare in particular could be transferred to a seabed-specific command.

A Seabed Command would focus entirely on seabed warfare. It could unite many of the currently disparate functions found within the surface, EOD, aviation, and oceanographic communities. Its purview would include underwater surveying and bathymetric mapping, search and recovery, placing and finding mines, testing and operating unmanned submersibles, and developing future technologies that will place the U.S. on the forefront of future seabed battlegrounds.

Why It Is Important

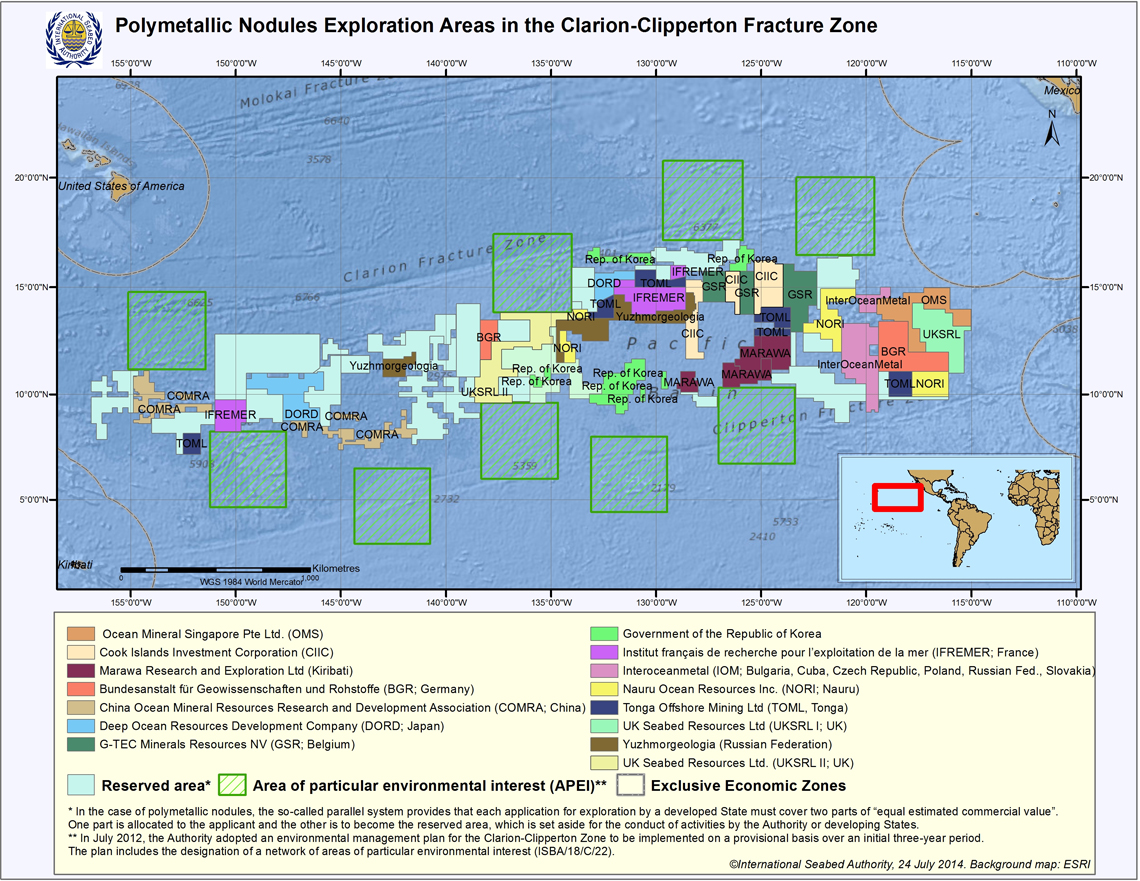

The seabed is the final frontier of the battlespace. Even low earth and geosynchronous orbits have plenty of military satellites, whether they are for communication or surveillance, but the seabed, except for mines and a few small expeditionary vessels, remains largely unexplored.

There are several reasons for this. For one, it’s hard to access. While the U.S. Navy has a few vehicles and systems that allow for deployment to deep depths, the majority of the seabed remains inaccessible, at least not quickly. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, this hasn’t been a huge problem. Except for in rare cases of submarine rescue, there has been little need for the Navy to deploy forces to extreme depths.

That is changing. Secretary of Defense Mattis has made it clear that in the coming years, threats from nations such as Russia and China will make conventional forces more relevant than they have been in the past 20 years. It is imperative that the U.S. Navy has a solution to rapidly deploy both offensive and defensive forces to the seabed, because right now it can’t.

While mine-hunting robots have been deployed to Arleigh Burke destroyers, it seems unlikely that in a full-scale war the Navy will be able to direct these assets to work full-time at seabed warfare. After all, they’re too valuable. The Arleigh Burke destroyer proved its mettle in Iraq; being able to place cruise missiles through the window of a building certainly has a deterrent effect. But this also means that any attempts to add mine warfare to the destroyers’ responsibilities will be put on the back burner, and that will allow enemies to gain an advantage on the U.S. Navy.

There is simply a finite amount of time, and the Sailors underway cannot possibly add yet more tasks to their already overflowing plate. It would take a great deal of time for Sailors onboard the destroyers to train and drill on seabed warfare, and that’s time they just don’t have. No matter how many ways you look at it, the surface fleet is already working at capacity.

What is needed is a new naval command, equipped with its own fleet of both littoral and deep-water ships and submarines, which focuses entirely on seabed warfare.

In this new command, littoral ships, like the new Freedom Class LCS, will be responsible for near shore seabed activities. This includes clearing friendly harbors of mines, placing mines in enemy harbors, searching for enemy submarines near the coast, and denying the enemy the ability to reach friendly seabeds.

The deep-water component will be equipped with powerful new technology that can seek out, map, and cut or otherwise exploit the enemy’s undersea communications cables on the ocean floor, while at the same time monitor, defend, maintain, and repair our own. It will also deploy stand-off style torpedo pods near enemy shipping lanes; they will be tasked with dominating the seabeds past the 12 nautical mile limit.

We have to be prepared to think of the next war between the U.S. and its enemies as total war. Supplies and the transfer of supplies between enemy countries will be a prime target for the U.S. Navy. We have to assume that in a full nation vs. nation engagement, the submarines, surface ships, aircraft carriers, and land-based aircraft will be needed elsewhere. Even if they are assigned to engage enemy shipping, there are just not enough platforms to hold every area at risk and still service the required targets.

For example, the U.S. will need the fast attacks to insert Special Forces troops, especially since the appetite to employ the Special Forces community has grown in the last 20 years. They will also be needed to do reconnaissance and surveillance. Likewise, the aircraft carriers will have their hands full executing strike missions, providing close air support to ground troops, working to achieve air superiority, and supporting Special Forces missions. Just like the surface fleet is today, the submarine fleet and the aircraft carriers will be taxed to their limit during an all-out war.

That’s why a seabed-specific command is needed to make the most of the opportunities in this domain while being ready to confront an adversary ready to exploit the seabed. Suppose that during a total war, the Seabed Command could place underwater torpedo turrets on the seabed floor, and control them remotely. A dedicated command could place, operate, and service these new weapons, freeing up both the surface and the submarine fleets to pursue other operations. Under control of Seabed Command, these cheap, unmanned torpedo launchers could wait at the bottom until an enemy sonar contact was identified and then engage. Just like pilots flying the MQ-9 Reaper control the aircraft from thousands of miles away, Sailors based in CONUS could operate these turrets remotely. Even the threat of these underwater torpedo pods would be enough to at least change the way an adversary ships crucial supplies across the ocean. If the pods were deployed in remote areas, it would force the enemy to attempt to shift shipping closer to the coast, where U.S. airpower could swiftly interdict.

The final component of Seabed Command would be a small fleet of submarines, equipped for missions like undersea rescue, repair, and reconnaissance. The submarines would also host saturation diving capabilities, enabling the delivery of personnel and equipment to the seafloor. Because these assets are only tasked with seabed operations, the Sailors would receive unique training that would make them specialists in operating in this unforgiving environment.

Conclusion

A brand new Seabed Command and fleet is order. It will be made up of both littoral and deep water surface ships, unmanned torpedo turrets that can be deployed to the ocean floor and operated from a remote base, and a small fleet of submarines specially equipped for seabed operations.

The U.S. Navy cannot rely on the surface warfare community to complete this mission; they are simply too busy as it is. While the submarine force might also seem like a logical choice, in a full-on nation vs. nation war, their top priorities will not be seabed operations. Only a standalone command and fleet will ensure America’s dominance at crush depth.

Joseph LaFave is a journalist covering the defense contracting industry, defense trends, and the Global War on Terror. He is a graduate of Florida State University and was an engineer at Lockheed Martin.

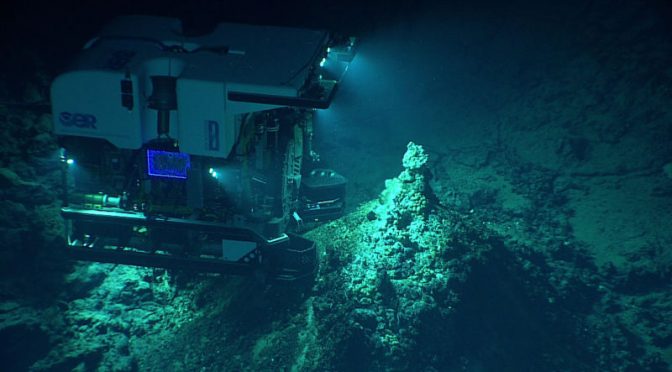

Featured Image: ROV Deep Discoverer investigates the geomorphology of Block Canyon (NOAA)