By Mark Munson

Sea power advocates traditionally justify the role of navies as a national security tool by their function in winning and deterring wars. The U.S. Navy’s current maritime strategy articulates this idea by stating that sea power is “the critical foundation of national power and prosperity and international prestige.”1 However, past wars at sea have been won by states or combatants in spite of significant naval disadvantages. The Spanish Civil War provides one such example of a less capable power defeating an enemy with a bigger navy. A successfully executed strategy can overcome a larger fleet, where victories by smaller navies can be enabled by factors like air power and the active support of willing allies, allowing them to successfully apply sea power in support of national objectives.

Pre-Uprising

In 1936, right-wing Spanish military officers (later referred to as “Nationalists,” an example of successful historical branding as they were actually the rebels in this case) mutinied against the republican government that had ruled Spain since the end of the monarchy in 1931. While the Spanish Civil War is not typically considered one of the major naval conflicts of the twentieth century, control of the seas around Spain, particularly the Strait of Gibraltar, was vitally important at the start of the conflict since most of the rebel troops were based across the strait in Spanish Morocco, where the Spanish Army had been conducting a brutal pacification campaign for decades.

The Spanish Legion (El Tercio, Spain’s attempt at replicating the French Foreign Legion) and Spanish Army units referred to as Regulares (composed of Moroccan natives) were at the core of the Army of Africa that the right-wing Nationalists would rely on in their revolt against the Republic’s Popular Front government. Moving those troops across the strait would require support from the Spanish Navy.

While some historians claim that senior naval officers coordinated with the eventual Spanish dictator Francisco Franco before the mutiny,2 others argue that General Emiliano Mola, the main organizer of the rising, had “made no serious provision for naval commitment to the plot,”3 assuming that “the Spanish Navy would remain impotent and neutral” after Spanish Army officers had rebelled.4 The aristocratic and “strongly monarchist” Navy officer corps was more socially homogenous than its Army counterpart, which had some “liberal pockets.” The mutineers gambled that most Spanish Navy officers would side with them, a move that would be borne out.

Immediately before the rising, however, the Republican government, suspecting a possible coup, had already deployed warships to the strait to deter a potential crossing from Africa.5 The Navy Minister, Jose Giral, had kept ships deployed away from potential strongholds of the mutineers, and more importantly, tasked “loyal telegraph operators” to monitor communications both ashore and afloat.6 Enlisted sailors, meanwhile, had also intuited the rising, holding a secret meeting in Ferrol on 13 July to prepare for a rebellion by their officers.7

That planning was timely. On 18 July, a civilian radio operator working at Navy headquarters in Madrid intercepted a message from Franco transmitted to senior officers encouraging them to rise up in support of the mutiny initiated the previous day by Army units in Morocco. Giral responded to the news by instructing all fleet radio operators to “to watch their officers, a gang of fascists,” and issuing a follow-up command “dismissing all officers who refused government orders.”8

Sorting Sides

Many Navy personnel first learned of the rising that day when they received Giral’s orders to attack rebel Army units.9 Disregarding the pleas of their officers to support the rebellion, crews of many Spanish Navy ships spread word of the rising, deposed their officers, and formed committees to run the ships.10 Onboard the battleship Jaime I, the crew “overwhelmed, imprisoned, and in many cases, shot those officers who seemed disloyal.”11 After the skirmish between officers and their men, the crew had a famous exchange with Madrid:

“Crew of Jaime I to ministry of marine. We have had serious resistance from the commanders and officers onboard and have subdued them by force…Urgently request instructions as to bodies.”

“Ministry of marine to crew Jaime I. Lower bodies overboard with respectful solemnity. What is your present position?”12

A similar series of events reportedly took place onboard the cruiser Miguel de Cervantes, whose officers reportedly “resisted the ship’s company to the last man.”13

The captain of the destroyer Sánchez Barcaiztegui, off the shore of North Africa near Melilla, attempted to sway the men to the cause of the mutineers, but after pleading his case he “was greeted by profound silence, which was interrupted by a single cry “To Cartagena!” This cry was taken up by the whole ship’s company.” After ousting their officers and bombarding Nationalist positions in Melilla and Ceuta, the crew returned in command of the ship to port in Cartagena, where the Navy base had remained loyal to the Republic.14 On station near Melilla, the officers of the destroyer Churruca remained in control because of a malfunctioning radio that had left all aboard oblivious to events.15 Once communications were restored, however, the crew seized control of the ship after it had delivered troops to Cadiz.16

Officers not killed during the rising were imprisoned ashore, where many were later executed.17 According to one account, “230 out of 675 naval officers on active service” were killed during the first months of the war.18 After rejecting the Ministry’s command to attack the rebels on 18 July, most naval officers were deposed by the crews per Giral’s orders, with chief engineers assuming duty as new commanding officers.19 By the time the Spanish Navy had sorted itself into two warring factions, the Republic was left with a tiny fraction of the former Spanish Navy’s senior uniformed leadership: only two of the 19 admirals, and two of the 31 commanding officers of large combatants sided with the Republic. According to one estimate, “only 10 percent of the Cuerpo General,” the Navy’s sea-going line officers, stayed loyal to the Republic.20 Those who stayed loyal were often “demoralized by the murder of their comrades and the insecurity of their own position.”21

It is unclear whether their exodus left the Republican fleet a leaderless and undisciplined rabble, or the officer corps’ preference for service with the Nationalists gave it an intangible, war-winning, leadership advantage. Regardless, the workers committees formed by the Republican sailors to replace the officers afloat failed to translate revolutionary zeal into victory at sea. Nikolai Kuznetsov, then a captain serving as the Soviet naval attaché in Madrid, recalled that the shipboard committees resulted in much talk but little action, citing a visit to the battleship Jaime I in which “the phrase ‘conquer or die’ was heard everywhere, but the anarchists neither conquered nor died.”22

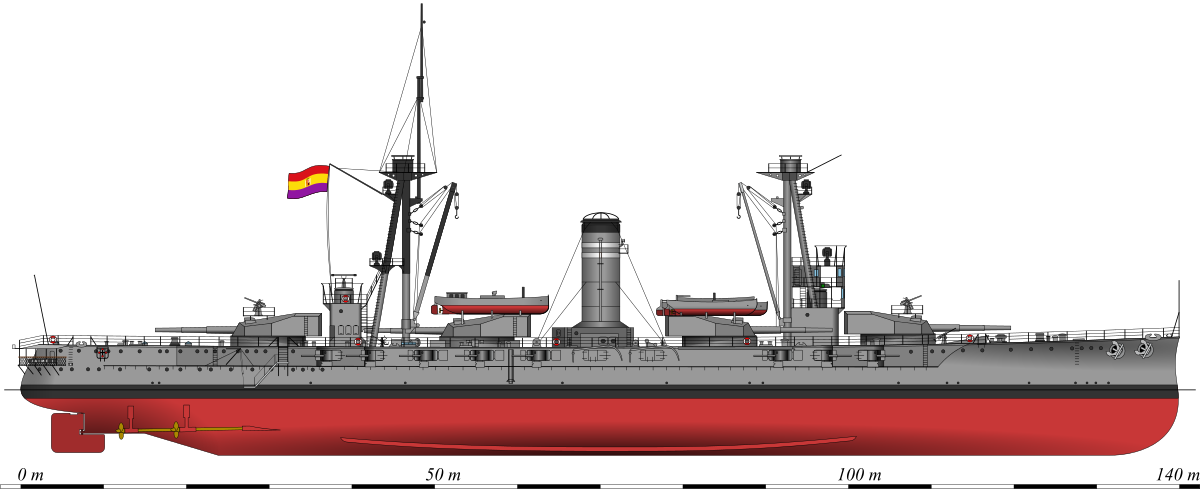

The enlisted crews did secure more of the fleet than their officers, particularly most of the newest combatants, including Jaime I, three cruisers, twenty destroyers, and twelve submarines. The Nationalists seized the battleship España from drydock, two cruisers, a destroyer, some gunboats, two submarines, and five Coast Guard vessels. Crucially, they also captured Canarias and Balaeres, two new cruisers under construction in Ferrol at the time of the rising.23

Somewhat mitigating their deficiency in numbers of ships, the Nationalists seized major naval bases on the Spanish mainland in Ferrol, Cadiz, and Algeciras, while the Republic was left with Cartagena and Mahon on the island of Minorca, both of which both had comparatively limited maintenance facilities. Republican control of major civilian ports and shipyards in Barcelona and Bilbao, along with two-thirds of Spain’s merchant fleet, ultimately failed to influence the course of the naval war.24

Nationalist Operations (The Rebels)

By late July 1936, the two Spanish navies had begun to contest the strait, since control of that chokepoint would prevent any Nationalist attempt to move their troops from Morocco. By early August the bulk of the Republican Navy was operating there, trying to bottle up the enemy Army of Africa25 as Italy began to deploy Savoia Marchetti 81 bombers (SM.81) to Nationalist bases in Morocco.26

When most of the Republican ships left the strait to replenish supplies in Cartagena on 5 August, the Nationalists immediately seized the initiative. The Italian bombers pounced on the few destroyers left behind, damaging Almirante Valdes and Lepanto, and clearing the way for the sealift of Nationalist troops to Spain.27 The German battleships Deutschland and Admiral Scheer, also operating near the strait at that time, likely deterred the Republican ships from interdicting the convoy of Franco’s troops.28

The Italians scattered the Republican fleet, allowing 3,000 men from the Army of Africa to cross by sea.29 The so-called “victory convoy”30 that sailed on “the day of the Virgin of Africa” was critical at that stage of the war. Those troops would form the bulk of the force that “cut off the Portuguese frontier from the republicans” and joined “forces with the Army of the North,” establishing the Nationalists firmly on the ground for the rest of the war.31

The German Luftwaffe also contributed to saving the Nationalist cause, with German air power playing a vital role in the airlift of troops essential to Nationalist logistics. Hitler reportedly said that “Franco ought to erect a monument to the glory of the Junkers Ju 52. It is the aircraft which the Spanish revolution has to thank for its victory.”32 “The first major airlift of troops in history” transported 1,500 troops in its first week. Eventually the German and Italian air forces transported up to 12,000 soldiers to Spain in the opening months of the war.33 The real impact of the airlift may have been qualitative rather than quantitative, however, with German aviation demonstrating Nazi commitment and thereby stiffening rebel resolve. While the number of men flown by the Nazis was significantly less than the number of troops ferried cross the strait by sea, it “had an enormous influence both on the nationalists’ morale and on the international assessment of their chances of victory.”34 While the airlift may not have been the decisive moment in the war, as “the Army of Africa would have got across eventually,”35 Hitler’s intervention is what turned “a coup d’etat going wrong into a bloody and prolonged civil war.”36

The war at sea was also one of allies, with the Nationalists benefiting from more active support from their German and Italian allies at sea than any aid the Republic received. Germany evaded the Republic’s blockade of their commercial shipping by using vessels registered in Panama, and the Nationalist Navy convoyed in Italian ships.37 The German and Italian navies steadily increased their support to the Nationalists throughout the early months of the war, organizing arms shipments and convoying them through the Republic’s “flimsy blockade,” monitoring the Republican fleet at sea, “openly transmitting periodic position reports,” and establishing formal liaison relationships with the Nationalist Navy.38 The Italian Navy also trained and equipped the Nationalist Navy with submarines and torpedo boats.39

The Italian Navy flagrantly abused the concept of neutrality to justify anchoring warships and landing marines in the nominally-neutral port of Tangier, claiming that they needed to evacuate endangered Italian citizens. By the time thousands of Italians and other third-country nationals had left the city, Italian forces had managed to deter the Republican Navy from entering the port and discouraged Republican loyalists from taking control of that vital haven on the southern side of the strait.40

Republican Operations (The State)

In contrast to the straightforward German and Italian support to the Nationalists, the Republic’s reliance on the Soviet Union subjected it to constraints and conflicting objectives. The German and Italian navies prevented the deployment of Soviet warships in the Spanish theater, and Nationalist forces could interdict Soviet-flagged merchant shipping that attempted to transit the Mediterranean.41 Soviet arms shipments to the Republic had to be carried by Spanish shipping, with British-flagged shipping carrying the bulk of “legitimate trade” like “oil, coal, food and other supplies.”42 But despite difficulties, including the lack of sympathy by most of the remaining senior Republican Navy officers for Soviet or Spanish communists, the Republican Navy was able to maintain maritime lines-of-communication with the Soviet Union- “between October 1936 and September 1937, over twenty large, mostly Spanish, transport ships made journeys from the Black Sea to Spain without difficulty.”43

Despite the success of those convoys, critics of the Soviet naval strategy correctly point out that it “was narrowly defensive and was essentially derived from the assumptions of inevitable material inferiority to imperialist navies which could only be defeated by a kind of proletarian guerilla warfare at sea.” This strategy made little sense for a Republican Navy that started the war with every “material and geographical capability to carry the war to the enemy.” Rather than taking the initiative, the Republic ceded use of the sea by limiting their scope of naval operations mainly to escorting Soviet shipping.44

Soviet influence had an operational impact later in 1936 as well. On 29 September, the Nationalist cruisers Almirante Cervera and Canarias sunk Almirante Ferrándiz and damaged Gravina at the battle of Cape Spartel,45 in what has been called the “turning point of the naval war.” Afterward “the Republican Navy would never regain the initiative or its confidence, while the Nationalist Navy would never lose them.” Kuznetsov had approved the diversion of Republican ships from the strait, but eventually acknowledged “it was a terrible blunder.”46

It should be noted, however, that the Soviets controlled the Republican Navy in virtually the same manner as they influenced Republican Army operations ashore during the first two years of the war.47 Ironically, the Spanish Communist Party vigorously criticized “the passivity of the Republican fleet,” not realizing that its caution at sea was dictated by a naval strategy crafted by Soviet officers to meet Soviet objectives.48 One assessment of Soviet assistance argues that “Stalin’s material aid kept the Republic temporarily alive, but his military advisers helped dig its grave.”49

Neutral or Complicit Onlookers?

While France and Great Britain tried to maintain neutrality in their relations with the two sides, the international regime they attempted to implement and enforce at sea actively harmed the Republican cause. The Non-Intervention Agreement of September 1936 not only failed to stop the flow of fighters and materiel to both sides, but one-sided adherence to the agreement by the “genuinely” neutral UK and the “formally” neutral France did little to diminish the flow of German, Italian, or Soviet aid into Spain.50 Franco-British neutrality did not extend to actually ensuring that other European powers behaved as neutrals, as they chose to overlook direct Italian and German naval participation in the hostilities.51

The French left-wing Popular Front government did make some moves to help the Republican government with which it had much ideological sympathy, but on a smaller scale than Italy or Germany aided the Nationalists. On the maritime front, however, even a minimal French commitment in support of the Republic was undercut by a British refusal to cooperate. Overtures by the French Navy’s Admiral Francois Darlan to the British to counter Italian and German naval support to the Nationalists were rebuffed in 1936.52 Lord Chatfield, the Royal Navy’s First Sea Lord, told Darlan that Franco was a “good Spanish patriot” and that the Royal Navy was “unfavourably impressed” by “the murder of the Spanish naval officers.”53

The British reluctance to support the Republic with Royal Navy operations afloat was not just officer-class solidarity with the Nationalist sympathies of their Spanish Navy peers, however. It also reflected larger geopolitical concerns and diverging imperial interests not aligned with the Anglo-French naval alliance. While fears of “combined Italian-German-Spanish naval operations” in the Mediterranean drove French planning, British desire for a rapprochement with Italy after disputes over the Italian invasion of Ethiopia in 1935 led to a less aggressive British policy.54

Conclusion

Despite its initial significant naval advantage, the Spanish Republic was ultimately defeated by the Nationalists in 1939. While both sides operated at sea throughout the conflict, the Republic had lost the naval war within the first few months. Historians have justifiably blamed the Republican Navy for its failure to keep the Army of Africa bottled up in Morocco, but it is unfair to attribute this failure to anarchist shipboard committees and the few officers that remained loyal to the government in Madrid. The smaller Nationalist fleet exploited air power and vigorous allied support to more effectively apply sea power in order to win the war. Sea power proved decisive in the Spanish Civil War, just not in the narrow understanding of naval strength typified by measuring numbers of vessels. Ships and other materiel of war are tools, and the Nationalists proved better at using theirs at sea between 1936 and 1939.

Lieutenant Commander Mark Munson is a naval officer assigned to Coastal Riverine Group TWO. The views expressed are solely those of the author and do not reflect the official viewpoints or policies of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

[1] A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower, March 2015.

[2] Antony Beevor, The Battle for Spain (New York: Penguin, 2006), 71.

[3] Hugh Thomas, The Spanish Civil War (New York: Harper & Row, 1977), 212.

[4] Willard C. Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” Naval War College Review 38, no. 1, (January/February 1984): 24.

[5] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 24.

[6] Thomas, 204.

[7] Beevor, 71-72.

[8] Beevor., 57, 72.

[9] Ibid., 71.

[10] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 25.

[11] Thomas, 243.

[12] Beevor, 72.

[13] Thomas, 243.

[14] Ibid., 72.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Beevor, 72.

[17] Thomas, 243.

[18] Ibid., 243 (footnote).

[19] Ibid., 227.

[20] Michael Alpert, “The Clash of Spanish Armies: Contrasting Ways of War in Spain, 1936-1939,” War in History 6, no. 3 (1999): 345.

[21] Thomas., 331-332.

[22] Ibid, 549.

[23] Ibid., 331-332.

[24] Ibid., 331-332.

[25] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 25.

[26] Ibid., 28.

[27] Ibid., 28; Michael Alpert, La Guerra Civil Española en el Mar (Madrid: Siglo XXI de España Editores, 1987), 92.

[28] Thomas, 370-371; Michael Alpert, “The Clash of Spanish Armies: Contrasting Ways of War in Spain, 1936-1939,” War in History 6, no. 3 (1999): 334.

[29] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 29; Thomas, 370-371; Beevor, 117-118.

[30] Paul Preston, Franco: A Biography (New York: Basic Books, 1994) 161-162.

[31] Thomas, 370-371.

[32] Hitler’s Table Talk: 1941-1944, trans. Norman Cameron and R.H. Stevens (New York: Enigma Books, 2000), 687.

[33] Beevor, 117-118.

[34] Ibid., 117-118.

[35] Ibid., 427.

[36] Preston, 160.

[37] Peter Gretton, “The Nyon Conference – The Naval Aspect,” The English Historical Review 90, no. 354 (January 1975): 103.

[38] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 30.

[39] Sullivan, 10.

[40] Ibid., 9.

[41] Alpert, “The Clash of Spanish Armies: Contrasting Ways of War in Spain, 1936-1939,” 348.

[42] Gretton, 103.

[43] Thomas, 549-550.

[44] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 32.

[45] Beevor, 144; Willard C. Frank, “Canarias, Adiós,” Warship International 2 (1979), accessed at http://www.kbismarck.org/canarias2.html.

[46] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 30-31.

[47] Ibid., 32.

[48] Ibid., 39.

[49] Ibid., 48.

[50] Gretton, 103.

[51] Michael Alpert, “The Clash of Spanish Armies: Contrasting Ways of War in Spain, 1936-1939,” 346.

[52] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 28.

[53] Thomas, 389.

[54] Frank, “Naval Operations in the Spanish Civil War,” 30.

Featured Image: The Spanish cruiser Canarias (Colorized by Irootoko Jr.)