By Andrea Daolio

“We have lost control of the seas to a nation without a navy, using pre-World War I weapons, laid by vessels that were utilized at the time of the birth of Christ.” –Rear Admiral Allen E. “Hoke” Smith

Mine warfare and anti-submarine warfare share many features, from the fact that both are very difficult and time-consuming tasks (often akin to finding a needle in a haystack). And despite how both submarines and mines achieved tremendous wartime success in the past, the peacetime effort and resources dedicated toward countering them are usually far less than what is required. By harnessing unmanned systems and machine learning, the U.S. Navy can bridge the gap between its own mine countermeasures capability and the growing mine warfare threat.

Historical Successes of Mine Warfare

During World War II, Operation Starvation which mined Japanese home waters severely disrupted Japanese maritime traffic and sunk more than 1.2 million tons of shipping for the loss of only 15 airplanes, while demanding only 5.7 percent of the XXI Bomber Command’s total sorties. Yet a few years later the U.S. Navy was unprepared when it had to face enemy mines itself in the Korean War, resulting in the delay of the amphibious landing at Wonsan. At the end of the war, the mine countermeasures forces, which accounted for less than two percent of all UN naval forces, had suffered 20 percent of naval casualties.

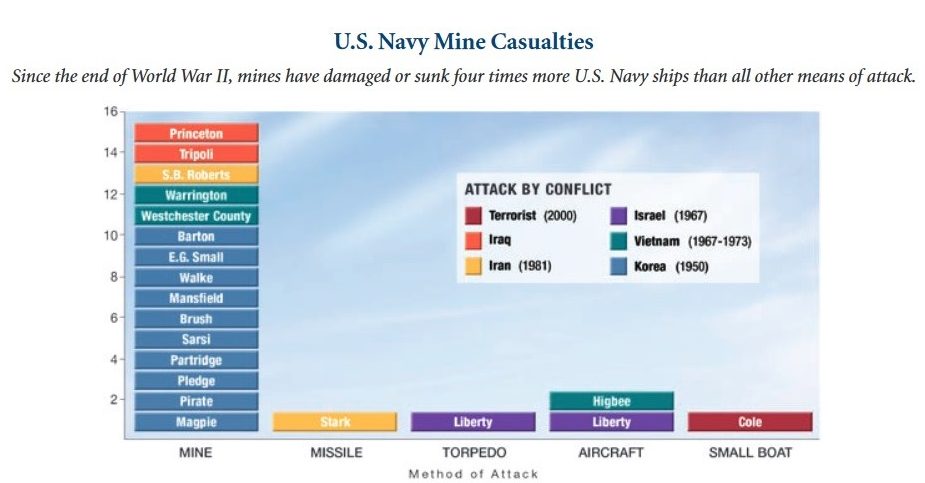

The 1987-1988 and 1991-1992 Gulf crises once again showed how deadly mines can be even for a totally superior force, damaging the USS Samuel B. Roberts (FFG-58), the flagship for Airborne Mine Countermeasures operations USS Tripoli (LPH-10) and the USS Princeton (CG-59). Since World War II, mines have damaged or sunk four more times more US Navy ships than all other weapons.

Russia has a fleet of 47 Mine Warfare vessels and inherited an arsenal of “upwards of 250,000” mines from the Soviet Union, while Iran is estimated to have between 3,000 and 20,000 mines and North Korea is said to have 50,000 mines.2 As if these numbers were not threatening enough, Iraq was able to damage two U.S. Navy ships by deploying only around 1,000 mines, many of them old types dating back to before World War I that can be replicated cheaply (contact mines cost as little as $1500) even by third world nations. More than 30 countries produce and more than 20 countries export mines, and even highly sophisticated versions of the weapon are available in the international arms trade.

NATO on the other hand has the largest MCM fleet in the world with 149 ships (as of 2016), but those ships are becoming old and obsolete (many are second-hand vessels retired by their original owner and then sold to smaller NATO countries). And only 7 percent of these vessels are part of the U.S. Navy. The need to renovate and enlarge this force is immediately apparent.

Countering the Threat

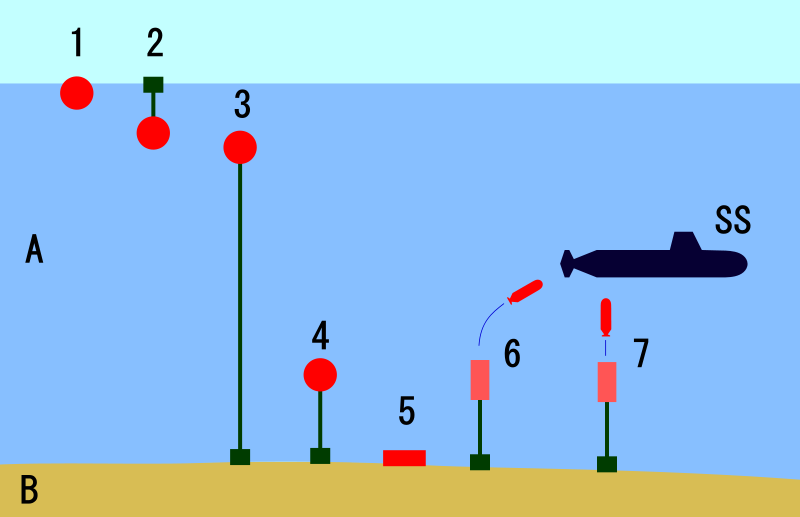

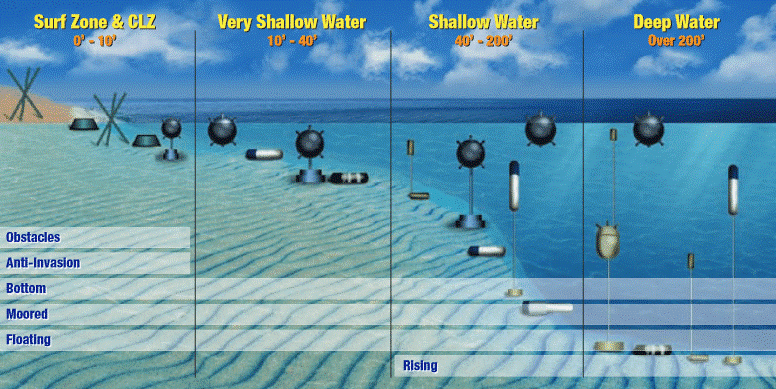

Mines can be put in place by aircraft, surface ships, pleasure boats, submarines, and combat divers and even from pickup trucks crossing bridges. They can be found from the surf zone to deep water (greater than 200 feet) and can be of many different and increasingly capable types. These range from simple contact mines to more complex magnetic, acoustic or pressure mines; from advanced mines that are a combination of the preceding types to computerized mines that can be even set to be detonated only by some specific ship type.

Mines are increasingly difficult to detect. The underwater environment is already a difficult medium to search through, as the currents, differences in salinity and temperature, and seafloor clutter (which is often littered with a vast array of debris) impede search. Meanwhile, mines are becoming even more elusive as stealthy mines made of fiberglass can be extremely difficult to detect. Furthermore, modern sonars are hardly capable enough to find advanced types of mines buried under the seafloor.

But even if mines have always had an advantage over mine countermeasures, new technologies are emerging that will be able to greatly reduce or even eliminate this advantage.

Once in the water, mines are difficult to detect, but even if mines can sometimes remain deadly for an extended period of time (such as how fishermen still get injured or killed in the Baltic Sea by leftover mines from the world wars), the damaging effects of the marine environment (from corrosion to marine growth) mean that mines can’t be reliably set in the sea for long periods of time.

Therefore an adversary will likely have to deploy mines shortly before a confrontation, and that will give the U.S. a golden opportunity to stop mines before they are deployed via a more favorable preventative strategy.3

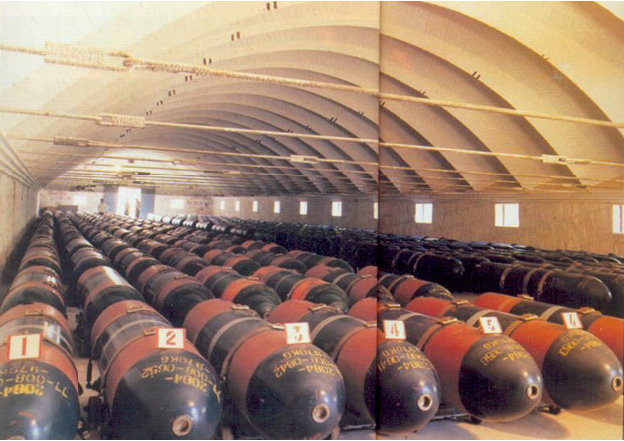

Satellites and High-Altitude Long-Endurance (HALE) drones will be able to detect signs of the major logistical efforts necessary to take mines from ammunition depots to the ports and then load them onto platforms, offering military and diplomatic opportunities to halt the mining operation.

Even if an enemy wants to place only a few mines, persistent surveillance (such as through satellites or unmanned systems with a long endurance capabilities) can monitor the area for signs of strangely behaving ships (the capture of the Iranian-improvised minelayer Iran Ajr is a good example of American forces stopping a mining operation before the mines are deployed).

Using unmanned aircraft for the task will ensure that the area will be monitored for long periods of time at a fraction of the cost and without risking lives. Machine learning and AI systems are already used for guiding military and civilian UAVs4 and even for monitoring,5 therefore these systems can be implemented in the software of an UAV to automatically tell the signs of suspect behavior of enemy assets without humans having to painstakingly watch hours of video feed and thus reducing the workload of the crew. Likewise, a fleet of small Unmanned Underwater Vessels (UUVs) can loiter in the suspected area and identify telltale signs of mining operations to stop it before it is too late. Similarly, underwater hydrophone arrays like those of the DADS and the Autonomous Off-Board Surveillance Sensor (AOSS) programs,6 even if intended to track quiet diesel-electric submarines, are capable of detecting airplanes, ships, and submarine mine-laying operations and monitor the water entry and the bottom impact of mines.

If these systems fail to stop the deployment of mines, once these are in the water, then the task gets more difficult and dangerous. Yet, unmanned systems and new technologies can greatly help the U.S. Navy in the task. Knifefish UUVs and Fleet-class USVs (Unmanned Surface Vessels) are already part of the MCM module of LCS ships and are a great step forward for mine countermeasures.7 The Knifefish has an endurance of up to 16 hours and uses onboard synthetic aperture sonar to detect floating or buried naval mines, identify them thanks to an onboard database and analytical computer, and mark them for the successive removal.

Machine learning and algorithms can also improve the ability of a UUV to recognize mines and identify objects on the seafloor. The NATO Science and Technology Organisation, Centre for Maritime Research and Experimentation (STO CMRE) of LaSpezia (Italy) has recently developed an advanced algorithm that will automate the time-consuming task of mine identification and disposal and further advances in this field will greatly improve MCM operations.8 Moreover, adding an advanced lightweight hydrophone array to UUVs will improve the capability to detect and localize underwater objects (and will give the UUV an improved secondary ASW capability).9

Likewise, unmanned systems can greatly help MCM operations in the air and on the surface. The experience gathered by DARPA with the ASW Continuous Trail Unmanned Vessel (ACTUV) could be used to create an advanced and completely autonomous MCM ship. Using powerful sensors, advanced automation software and MCM gear, an MCM ACTUV will be able to take many of the tasks now given to the Avenger-class minesweepers. A fully autonomous large fleet of inexpensive unmanned UUVs and USVs could sweep large portions of the sea while avoiding all risk to sailors.

While ships, USVs, and UUVs are the best platforms to neutralize mines, airplanes and helicopters are the fastest platforms to sweep the sea. The laser-based ALMDS (Airborne Laser Mine Detection System) and the unmanned COBRA (Coastal Battlefield Reconnaissance and Analysis System) have recently entered service, but more systems can be deployed in the future.10 UAVs are the perfect choice for persistent reconnaissance and can be adapted for the MCM task and augmented to field the COBRA and ALMDS systems.

While the Navy arguably gives less attention to mine countermeasures than it deserves, it gives even lesser attention to its own offensive mining capability. If the U.S. Navy wants to maintain a solid deterrent against rivals then it should improve and expand its own mine arsenal. The new Hammerhead mine and the Clandestine Delivered Mine (CDM) are a good step in the right direction and more should follow.11 But the vast majority of U.S. mines are Quickstrike mines converted from general-purpose bombs. Dedicated bottom and buried advanced mines (similar to the advanced British Stonefish mine) should be developed and the number of platforms able to deploy mines should be expanded to include UAVs, USVs, and UUVs. Moreover, air-launched mines should get extended-range winged kits similar to those employed by the HAAWC High Altitude ASW Weapons Concept torpedo to give launching aircraft the ability to deploy the mine much further away from enemy positions.12

Conclusion

“Hoke’s right: when you can’t go where you want to, when you want to, you haven’t got command of the sea. And command of the sea is the rock-bottom foundation of all our war plans. We’ve been plenty submarine-conscious and air-conscious. Now we’re going to start getting mine-conscious—beginning last week.” –Admiral Forrest P. Sherman, USN Chief of Naval Operations October, 1950

Until recently the task of minesweeping has been extremely dangerous for sailors, but with new technologies such as unmanned systems and machine learning, it is time to invest heavily in these avenues of capability and convert a greater part of the U.S. Navy to fully autonomous and unmanned MCM operations.

The importance of mine warfare and of mine countermeasures for any modern Navy can never be stressed enough. Given how mining can achieve great results and inflict huge losses with relatively low risk and cost argues for greater investment in these weapons and the means to counter them.

Andrea Daolio, from Italy, has an engineering background and a longstanding passion for wargaming and for geopolitical, historical, and military topics. He has been a finalist in New York’s MTA Genius Transit Challenge. He is currently collaborating with video game developer Slitherine on the popular wargame Command: Modern Air/Naval Operations. His views are his own.

References

[1] Andrew Erickson, Chinese Mine Warfare, http://www.andrewerickson.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/09/China-Maritime-Study-3_Chinese-Mine-Warfare_Erickson-Goldstein-Murray_200906.pdf

[2] Sydney J. Freedberg jr., Minefields At Sea: From The Tsars To Putin

[3] Sydney J. Freedberg jr., Sowing The Sea With Fire: The Threat Of Sea Mines

[4] Marcus Roth, AI in Military Drones and UAVs – Current Applications, https://emerj.com/ai-sector-overviews/ai-drones-and-uavs-in-the-military-current-applications/

[5] Luis F. Gonzalez , Glen A. Montes , Eduard Puig , Sandra Johnson , Kerrie Mengersen and Kevin J. Gaston , Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) and Artificial Intelligence Revolutionizing Wildlife Monitoring and Conservation, https://www.mdpi.com/1424-8220/16/1/97/htm

[6] Naval Mine Warfare: Operational and Technical Challenges for Naval Forces, https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10176/naval-mine-warfare-operational-and-technical-challenges-for-naval-forces

[7] Sydney J. Freedberg jr., From Sailors To Robots: A Revolution In Clearing Mines

[8] NATO CMRE, Autonomous Naval Mine Countermeasures, https://www.cmre.nato.int/about-cmre/fact-sheets/1292-autonomous-naval-mine-countermeasures-1/file

[9] Venugopalan Pallayil, Ceramic and Fibre Optic Hydrophone as Sensors for Lightweight Arrays – aComparative Study, https://arl.nus.edu.sg/twiki6/pub/ARL/BibEntries/venu_oceans_anchorage17.pdf

[10] Captain Danielle George, U.S. NAVY Mine Warfare Programs, https://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/Exhibits/SNA2019/MineWarfare-George.pdf?ver=2019-01-17-133139-817

[11] Joseph Trevithick, US is betting big on Naval Mine Warfare with these Sub-launched and Air-dropped types, https://www.thedrive.com/the-war-zone/25235/the-u-s-is-getting-back-into-naval-mine-warfare-with-new-sub-launched-and-air-dropped-types

[12] MK 54 Lightweight Torpedo and High-Altitude Anti-Submarine Warfare Capability (HAAWC), https://www.dote.osd.mil/pub/reports/FY2017/pdf/navy/2017mk54.pdf

Featured Image: September 22, 1987 – Contact mines partially covered by a tarpaulin on the deck of the captured Iranian mine-laying ship Iran Ajr (PH3 Cleveland, U.S. National Archives)