By Jason Lancaster

Introduction

The Marine Corps is an expeditionary crisis response force designed to project power globally from the sea. For the first time in a generation the shape of the Corps is changing and returning to its maritime roots. Closer integration with the Navy means that as in the Second World War, the Marine Corps will be a force provider for the maritime fight, potentially extending to the undersea domain. General Berger stated, “the undersea fight will be so critical in the High North and in the western Pacific that the Marine Corps must be part of it.”1 During World War II, Marine aviation units flew anti-submarine patrols from escort carriers and island bases in the Pacific defending the sea lanes from Japanese submarines.2 Today, the Marine Corps needs to invest in ASW-capable aircraft to support the ASW fight from the sea and ashore.

Today, the Navy has a major capability gap in anti-submarine warfare. In the 1980s, the Navy relied on land-based long-range maritime patrol planes, an ASW screen consisting of surface combatants, carrier-based medium-range ASW aircraft like the S-3B Viking, and short-range helicopters for localization and engagement. The Navy eliminated the S-3B Viking in 2009 with no replacement. This elimination removed medium-range ASW aircraft from the carrier strike group, and in a modern conflict with Russia or China, this gap could have catastrophic results. Both nations are increasing the number and capabilities of their submarines. Many of those submarines can engage surface ships with missiles from beyond 200 nautical miles, beyond the capability of organic carrier strike group ASW assets. The Navy has not taken enough steps to address the vulnerability of its major formations to submarines. The lack of organic ASW capabilities in amphibious ready groups (ARGs) makes them even more vulnerable than a CSG. ASW is a role the Marines have not conducted since World War II, but it is a vital role they must fill in the future.

Anti-Submarine Warfare

In its most simple form, ASW is placing sensors in positions to find submarines and kill them. The Navy uses surface ships, submarines, and aircraft to place sensors in positions to detect, classify, and engage submarines. The U.S. Navy uses two main frameworks for ASW: Theater ASW (TASW) and Strike Group ASW (SGASW). The role of TASW is to detect, track, classify, and engage submarines throughout an entire theater. In conflict the primary objective is to sink as many submarines as possible. SGASW is concerned with protecting the high value unit (HVU) from submarines. Success for SGASW is never being shot at. With good intelligence and communications with the TASW Commander, speed and maneuver may enable a strike group to avoid slow-moving diesel submarines.

The current concept to defend an ARG from submarines relies completely on non-organic aircraft and surface escorts assigned to the ARG as required. Unfortunately, the Navy’s ability to provide sufficient escorts for aircraft carriers and ARGs is decreasing. Despite NDAA 2017 requirements for a fleet of 350 ships, the number of surface ships in the Navy is decreasing. The 2023 proposed Navy budget included the decommissioning of 22 cruisers, 9 littoral combat ships, and the elimination of the LCS ASW mission package. The P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol planes are excellent ASW platforms, but are limited in quantity, and primarily work for the TASW Commander. Although an important mission, protecting the ARG is only one of many tasks for the TASW Commander. During a period with multiple submarine prosecutions occurring across a theater, the P-8 inventory may not enable 24-hour coverage of the ARG.

The Navy and Marine Corps should combine assets to create an organic air ASW squadron. The Navy can contribute existing MH-60Rs and the Marine Corps should contribute a new medium endurance Marine ASW aircraft. These platforms will fill the gaps in ASW coverage and protect the ARG’s main battery, its Marine Expeditionary Unit.

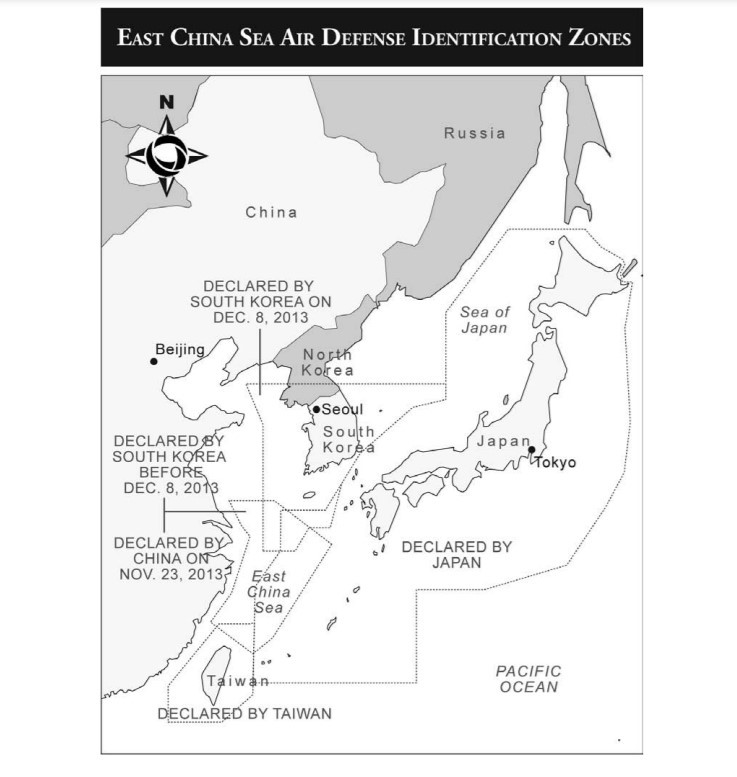

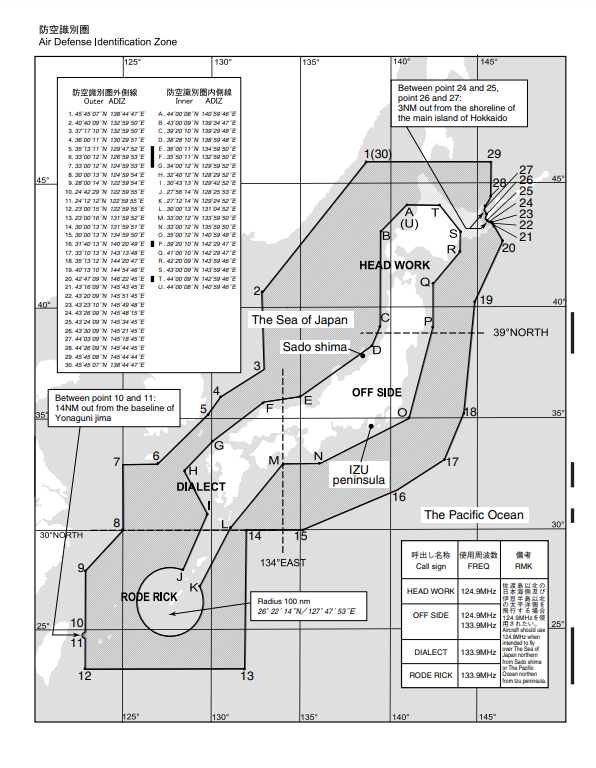

These assets can also operate from expeditionary advanced bases, which can be well-positioned to interdict submarines in chokepoints. In the Pacific, expeditionary bases positioned along the first island chain can cover the key chokepoints Chinese submarines must navigate to break out into larger oceans and seas. These chokepoints greatly simplify the challenge of locating and interdicting submarines, and Marine aerial ASW assets could be poised to pounce on contacts and maintain layers of sensors.

Marine ASW assets positioned in the High North, especially along the Norwegian coast, could make significant contributions to undersea capability and awareness by virtue of proximity to the Russian Northern Fleet’s main base at Severomorsk. With the accession of Finland and Sweden to NATO, Marines can help bolster undersea capability throughout the Baltic Sea.

A medium-range ASW aircraft should be able to conduct ASW patrols 200-300 nautical miles away from the ARG or expeditionary base for at least 4-6 hours, while carrying sufficient sonobuoys and torpedoes to detect, classify, and engage a hostile submarine. In order to save time and money on sensor development, the radar, sonobuoy processing system, EW suite, and sonobuoy launchers from an MH-60R can be utilized aboard a different aircraft. The Marine Corps has several options for developing a new medium endurance ASW aircraft. Two options are the MV-22 and the MQ-9B.

Multiple reconfigurations of the ARG and MEU make the present the perfect time to eliminate the ARG ASW gap by introducing Marine ASW assets. The introduction of the F-35B into the Air Combat Element (ACE) is changing the composition of the ACE. The Marines are experimenting with 8-10 F-35Bs instead of 6 AV-8s, which reduces space available on the LHD for MV-22s. The planned decommissioning of the Dock Landing Ship (LSD) is also shifting the composition of the ARG. The LSD had a large flight deck but no hangar and no permanent flight deck crew, limiting the LSD to flight deck or well deck operations.

The LPD-17 class has a large flight deck capable of operating two MV-22s simultaneously and a hangar designed to conduct maintenance on an MV-22, or holding two MH-60s. The LPD’s air department enables simultaneous well deck and flight deck operations. The elimination of the LSD and its replacement with an ARG composed of an LHD/LHA and two LPDs drastically increases the aviation capabilities inherent in the ARG. The Navy-Marine Corps team should take advantage of that shift to develop an organic ASW capability.

Option 1: Existing Airframes

Force Design 2030 planned to divest three MV-22 squadrons. The FD2030 2022 update stated that instead the Marines will shift from 14 squadrons composed of 12 aircraft to 16 squadrons of 10 aircraft.3 Instead of eliminating those eight aircraft, the Marine Corps should instead make a 17th squadron of 10 aircraft that is equipped for ASW. This squadron should be collocated at NAS North Island with the Navy’s MH-60R squadrons or at NAS Jacksonville with the P-8 and MH-60R squadrons so that Marine ASW aviators can train with their Navy counterparts.

Marine Corps experiments with more F-35Bs and fewer MV-22s aboard the LHD suggest that instead of eliminating surplus MV-22s, they could be converted into ASW aircraft. These reconfigured aircraft would utilize the MH-60Rs electronics/ASW suite to save time on fielding and development as well as saving resources on spare parts and training. NAVAIR would need to determine whether the airframe has sufficient electrical power generation to support the additional sensors. The Navy has sent MH-60R detachments on ARG deployments before, and their sensor suite is useful for ASW and surface warfare.

Another ASW MV-22 option is to utilize the multi-static active coherent (MAC) buoys. NAVAIR would have to determine whether the buoy processing system would fit into an MV-22, but MAC buoys are the most capable sonobuoys in the U.S. Navy’s inventory and their utilization by a medium-range ASW aircraft would dramatically increase the lethality of the ARG’s ASW capability. Foreign military sales could make this platform a force multiplier and reduce overall program cost. Spain, Turkey, Australia, and South Korea all operate LHDs and MH-60Rs. An MV-22 equipped with MH-60R sensors would increase allied ASW capabilities without adding additional sensor training and logistics pipelines for their forces. France, Britain, Italy, and Japan also operate aircraft carriers or LHDs and might be interested in a medium-range ASW platform. A successful platform could even be bought by the Navy for integration into the carrier air wing and used to eliminate the CSG’s ASW gap.

Option 2: UAVs

An alternative medium-range ASW aircraft is the MQ-9B Sea Guardian. The Marine Corps is already purchasing 18 MQ-9s from General Atomics, with the desire to acquire more. The Air Force is looking to transfer 100+ MQ-9s to another service. General Atomics has developed an ASW and ISR sensor kit for the MQ-9 Reaper, and states an ASW mission radius of 1,613NM or 25 hours aloft. In 2021, General Atomics signed a $980 million contract with Australia to buy 12 MQ-9Bs which was canceled in 2022.4 They carry sonobuoys and radar for detection and classification of submarines, but currently lack torpedoes to prosecute engagements. The lack of antisubmarine armament is a major drawback for these aircraft, but these aircraft have participated in fleet exercises and are available today.5

General Atomics has also developed a kit that converts existing MQ-9s into short takeoff and landing (STOL) platforms without diminishing the range. This capability would enable MQ-9Bs to operate extended ASW patrols from the LHD and expeditionary bases. In April 2021, the MQ-9B participated with other unmanned systems during the Unmanned Integrated Battle Problem Exercise.6 This exercise demonstrated the ability of unmanned systems to effectively integrate into the navy’s fleet architecture. The USMC and USN should experiment with the STOL MQ-9B Sea Guardian during exercises like Talisman Saber 23.

Conclusion

In World War II, Marine aircraft operating from islands and escort carriers provided ASW aircraft to the fight. The Marines have not been required to conduct ASW operations since. The Navy will have significant difficulty resourcing all of the escort requirements for carrier strike groups, amphibious ready groups, and TASW missions. Without organic ASW aircraft the ARG is vulnerable to submarines, especially sub-launched long-range missiles.

The Marine Corps has two rapid options for establishing an ASW capability – a modified MV-22 or the MQ-9B Sea Guardian. Although the Corps has not planned to acquire ASW aircraft, the Commandant’s thoughts on the importance of ASW in the High North and the western Pacific combined with the ARG’s vulnerability means that consideration for a platform must be considered. The Commandant is divesting of legacy equipment and end strength to invest in future equipment. With the Navy’s shortage of ASW assets, it makes sense for the Marine Corps to support the maritime fight not just with land-based anti-surface fires and sensing, but also with its own ASW aircraft.

LCDR Jason Lancaster is a Surface Warfare Officer. He has served at sea aboard amphibious ships, destroyers, and a destroyer squadron. Ashore, he has worked on various N5 planning staffs. He is an alumnus of Mary Washington College and holds an MA in History from the University of Tulsa. His views are his own and do not reflect the official position of the U.S. Navy or Department of Defense.

References

1. Berger, David (2020, November). Marines Will Help Fight Submarines. Proceedings.

2. Marine Scout Bombing Squadron Three Four Three. (1945). VMSB-343 – War Diary, 4/1-30/45. US Marine Corps.

3. United States Marine Corps. (2022). Force Design 2030 Annual Update May 2022. Washington DC: United States Marine Corps.

4. Clark, C. (2022, April 1). Aussies ‘secretly cancel’ $1.3B AUD drone deal; Nixing French subs may cost $5B . Breaking Defense.

5. General Atomics. (2022, April 5). Versatile multi-domain MQ-9B SeaGuardian has revolutionized anti-submarine warfare . Breaking Defense.

6. Office of Naval Research Strategic Communications. (2021, April 22). Unmanned Capabilities Front and Center During Naval Exercise. US Navy Press Release.

Featured Image: PHILIPPINE SEA (March 27, 2019) F-35B Lightning II aircraft, assigned to Marine Fighter Attack Squadron (VMFA) 121, and MV-22 Ospreys, assigned to Marine Medium Tiltrotor Squadron (VMM) 268, are secured to the flight deck of the amphibious assault ship USS Wasp (LHD 1). (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Daniel Barker)