This piece was originally published by the Jamestown Foundation. It is republished here with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By John Costello

On December 31, 2015, Xi Jinping introduced the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF; 火箭军), Strategic Support Force (PLASSF; 战略支援部队), and Army Leadership Organ. The move came just within the Central Military Commission’s deadline to complete the bulk of reforms by the end of the year. Most media coverage has focused on the Rocket Force, whose reorganization amounts to a promotion of the PLA Second Artillery Force (PLASAF) to the status of a service on the same level of the PLA Army, Navy, and Air Force. However, by far the most interesting and unexpected development was the creation of the SSF.

According to official sources, the Strategic Support Force will form the core of China’s information warfare force, which is central to China’s “active defense” strategic concept. This is an evolution, not a departure from, China’s evolving military strategy. It is a culmination of years of technological advancement and institutional change. In the context of ongoing reforms, the creation of the SSF may be one of the most important changes yet. Consolidating and restructuring China’s information forces is a key measure to enable a number of other state goals of reform, including reducing the power of the army, implementing joint operations, and increasing emphasis on high-tech forces.

The Strategic Support Force in Chinese Media

Top Chinese leadership, including President Xi Jinping and Ministry of Defense spokesman Yang Yujun have not provided significant details about the operational characteristics of the SSF. Xi has described the SSF as a “new-type combat force to maintain national security and an important growth point of the PLA’s combat capabilities” (MOD, January 1).

On January 14, the SSF’s newly-appointed commander, Gao Jin (高津) said that the SSF will raise an information umbrella(信息伞) for the military and will act as an important factor in integrating military services and systems, noting that it will provide the entire military with accurate, effective, and reliable information support and strategic support assurance (准确高效可靠的信息支撑和战略支援保障) (CSSN, January 14). [1]

Senior Chinese military experts have been quick to comment on the SSF, and their interviews form some of the best and most authoritative insights into the role the new force will play in the Chinese military. For instance, on January 16th, the Global Times quoted Song Zhongping (宋忠平), a former PLASAF officer and a professor at the PLARF’s Equipment Research Academy, who described SSF as as a “fifth service” and, contrary to official reports, states it is not a “military branch” (兵种) but rather should be seen as an independent military service (军种) in its own right. [2] He continues by stating that it will be composed of three separate forces or force-types: space troops (天军), cyber troops (网军), and electronic warfare forces (电子战部队). The cyber force would be composed of “hackers focusing on attack and defense,” the space forces would “focus on reconnaissance and navigation satellites,” and the electronic warfare force would focus on “jamming and disrupting enemy radar and communications.” According to Song, this would allow the PLA to “meet the challenges of not only traditional warfare but also of new warfare centered on new technology” (Global Times, January 16).

By far the most authoritative description of the Strategic Support Force comes from People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) Rear Admiral Yin Zhuo (尹卓). As a member of both the PLAN Expert Advisory Committee for Cybersecurity and Informatization (海军网络安全和信息化专家委员会) and the All-Military Cybersecurity and Informatization Expert Advisory Committee (全军网络安全和信息化专家委员会, MCIEAC) formed in May 2015, Yin is in the exact sort of position to have first-hand knowledge of the SSF, if not a direct role in its creation.

In an interview published by official media on January 5th, 2016, Yin stated that its main mission will be to enable battlefield operations by ensuring the military can “maintain local advantages in the aerospace, space, cyber, and electromagnetic battlefields.” Specifically, the SSF’s missions will include target tracking and reconnaissance, daily operation of satellite navigation, operating Beidou satellites, managing space-based reconnaissance assets, and attack and defense in the cyber and electromagnetic spaces” and will be “deciding factors in [the PLA’s] ability to attain victory in future wars” (China Military News, January 5).

Yin also foresees the SSF playing a greater role in protecting and defending civilian infrastructure than the PLA has in the past:

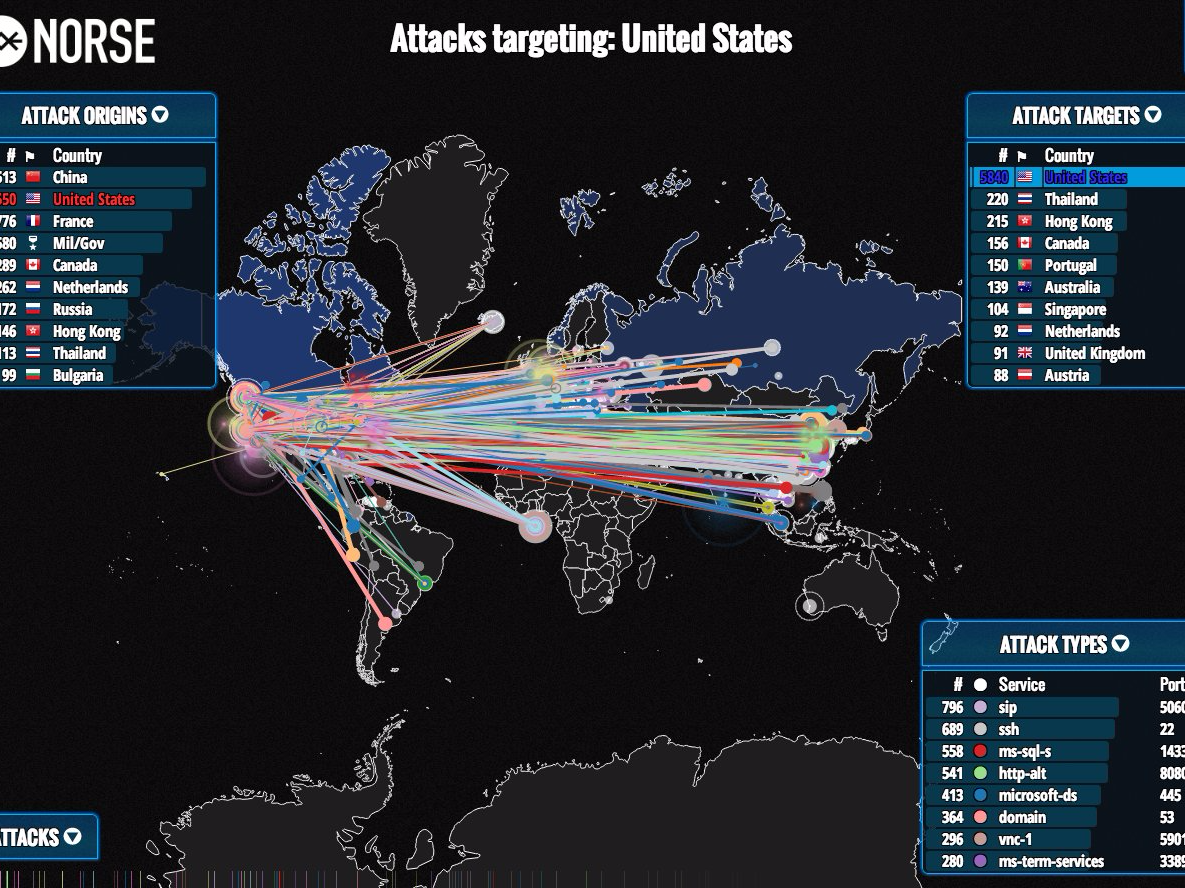

“[The SSF] will play an important role in China’s socialist construction. Additionally, China is facing a lot of hackers on the internet which are engaging in illegal activities, for example, conducting cyber attacks against government facilities, military facilities, and major civilian facilities. This requires that we protect them with appropriate defense. The SSF will play an important role in protecting the country’s financial security and the security of people’s daily lives” (China Military News, January 5).

Yang Yujun, MND spokesman, also suggested that civilian-military integration will form a portion of the SSF’s mission, but stopped short of clarifying whether this meant the force will have a heavy civilian component or will be involved in defending civilian infrastructure, or both (CNTV, January 2).

Yin noted that the SSF will embody the PLA’s vision of real joint operations. In Yin’s view, military operations cannot be divorced from “electronic space,” a conceptual fusion of the electromagnetic and cyber domains. The SSF will integrate “reconnaissance, early warning, communications, command, control, navigation, digitalized ocean, digitalized land, etc. and will provide strong support for joint operations for each military service branch.” Indeed, this view was also echoed by Shao Yongling (邵永灵), a PLARF Senior Colonel who is currently a professor at the PLA’s Command College in Wuhan. She suggested that the SSF was created to centralize each branch of the PLA’s combat support units, where previously each service had their own, resulting in “overlapping functions and repeat investment.” Consolidating these responsibilities in a central force would allow the military to “reduce redundancies, better integrate, and improve joint operational capabilities” (China Military News, January 5).

Taken together, these sources suggest that at its most basic, the SSF will comprise forces in the space, cyber, and electromagnetic domains. Specifically, sources indicate the SSF will most likely be responsible for all aspects of information in warfare, including intelligence, technical reconnaissance, cyber attack/defense, electronic warfare, and aspects of information technology and management.

Force Composition

Rear Admiral Yin’s comments in particular suggest that at a minimum the SSF will draw from forces previously under the General Staff Department’s (GSD) subordinate organs, to include portions of the First Department (1PLA, operations department), Second Department (2PLA, intelligence department), Third Department (3PLA, technical reconnaissance department), Fourth Department (4PLA, electronic countermeasure and radar department), and Informatization Department (communications).

The “Joint Staff Headquarters Department” (JSD) under the Central Military Commission will likely incorporate the 1PLA’s command and control, recruitment, planning, and administrative bureaus. Information support organs like the meteorology and hydrology bureau, survey and mapping bureau, and targeting bureau would move to the SSF.

The GSD’s intelligence department, the 2PLA will likely move to the SSF, although there is some question as to whether it will maintain all aspects of its clandestine intelligence mission, or this will be moved to a separate unit. The Aerospace Reconnaissance Bureau (ARB), responsible for the GSD’s overhead intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance mission will most likely form the center of the SSF’s space corps. The 2PLA’s second bureau, responsible for tactical reconnaissance, will also move to the SSF. This will include one of its primary missions: operating China’s long-range unmanned aerial vehicles (UAV).[3]

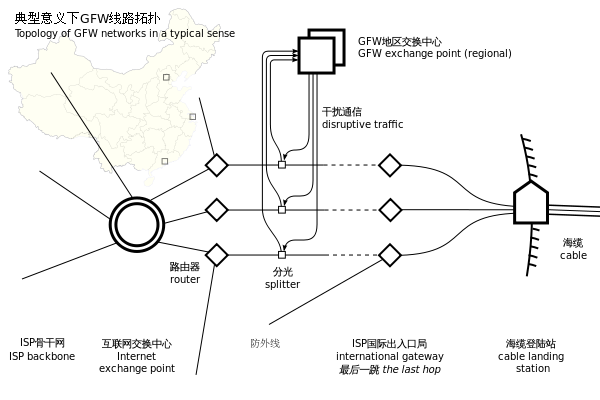

The SSF will unify China’s cyber mission by reducing the institutional barriers separating computer network attack, espionage, and defense, which have been “stove-piped” and developed as three separate disciplines within the PLA. The 3PLA’s technical reconnaissance and cyber espionage units will likely move, including the national network of infamous technical reconnaissance bureau’s (TRB), the most famous of which is Unit 61398. The 4PLA’s electronic countermeasures mission will likely form the core of a future electronic warfare force under the SSF, and the its secondary mission of computer network attack (CNA) will also likely also move under the SSF.

Finally, the entirety of the Informatization Department will likely move to the SSF. This will unify its mission, which has expanding over the years to include near all aspects of the support side of informatization, including communications, information management, network administration, computer network defense (CND), and satellite downlink.

Drawing the bulk of the SSF from former GSD organs and subordinate units is not only remarkably practical, but it is also mutually reinforcing with other reforms. Firstly, it reduces the power and influence of the Army by removing its most strategic capabilities. Previously the PLA Army was split into two echelons, its GSD-level headquarters departments (部门) and units (部队) and Military Region-level (MR; 军区) operational units. GSD units did not serve in combat or traditional operational roles, yet constituted some of China’s most advanced “new-type” capabilities: information management, space forces, cyber espionage, cyber-attack, advanced electronic warfare, and intelligence, reconnaissance, and surveillance. The creation of the Army Leadership Organ effectively split the Army along these lines, with lower-echelon forces forming the PLA Ground Forces and the higher-echelon units forming the Strategic Support Force.

Secondly, separating these capabilities into a separate SSF allows the PLA Army to concentrate on land defense and combat. Nearly all personnel staffing the supposedly joint-force GSD units were Army personnel and by-and-large these units were considered Army units, despite serving as the de facto joint strategic support units for the entire PLA military. Giving the SSF its own administrative organs and personnel allows the PLA Army to concentrate solely on the business of ground combat, land defense, and fulfilling its intended roles in the context of China’s national defense strategy.

Finally and most importantly, separating the second, third, fourth, and “fifth” departments—as the Informatization Department is sometimes called—into their own service branch allows them to be leveraged to a greater degree for Navy Air Force, and Rocket Force missions. More than anything, it allows them to focus on force-building and integrating these capabilities across each service-branch, thereby enabling a long-sought “joint-force” capable of winning wars.

In many ways, taking GSD-level departments, bureaus, and units and centralizing them into the Strategic Support Force is making official what has long been a reality. GSD-level components have nearly always operated independently from regional Group Army units. Separating them into a separate service is less of an institutional change and more of an administrative paper-shuffle.

Integrated Information Warfare

The Strategic Support Force will form the core of China’s information warfare force, which is central to China’s strategy of pre-emptive attack and asymmetric warfare. China’s new military reforms seek to synthesize military preparations into a “combined wartime and peacetime military footing.” These “strategic presets” seek to put China’s military into an advantageous position at the outset of war in order to launch a preemptive attack or quickly respond to aggression. [4] This allows China to offset its disadvantages in technology and equipment through preparation and planning, particularly against a high-tech opponent—generally a by-word for the United States in PLA strategic literature.

These presets require careful selection of targets so that a first salvo of hard-kill and soft-kill measures can completely cripple an enemy’s operational “system of systems,” or his ability to use information technology to conduct operations. Achieving this information dominance is necessary to achieve air and sea dominance, or the “three dominances.” [5] A PLA Textbook, The Science of Military Strategy, (SMS) specifically cites space, cyber, and electronic warfare means working together as strategic weapons to achieve these ends, to “paralyze enemy operational system of systems” and “sabotage enemy’s war command system of systems.” [6] This includes launching space and cyber-attacks against political, economic, and civilian targets as a deterrent. The Strategic Support Force will undoubtedly play a central role as the information warfare component of China’s warfare strategy, and will be the “tip of the spear” in its war-plans and strategic disposition.

Remaining Questions

Despite what can be culled and answered from official sources and expert commentary, significant questions remain regarding the structure of Strategic Support Force and the roles it will play. For one, it is unclear how the Strategic Support Force will incorporate civilian elements into its ranks. Mentioned in 2015’s DWP and the more recent reform guidelines, civilian-military integration is a priority, but Chinese official sources have stopped short in describing how these forces will be incorporated into military in the new order (MOD, May 26, 2015). Previously, the General Staff Department research institutes, known as the “GSD RI’s,” acted as epicenters of civilian technical talent for strategic military capabilities. If the Strategic Support Force is primarily composed of former GSD units, then these research institutes will be ready-made fusion-points for civilian-military integration, and may take on a greater role in both operations and acquisition. Even so, the civilian piece is likely to prove vital, as they will undoubtedly serve as the backbone of China’s cyber capability.

Secondly, it is unknown specifically what forces will compose the Strategic Support Force, or the full extent of its mission. When official sources say “new-type” forces, they could mean a wide range of different things, and the term can include special warfare, intelligence operations, cyber warfare, or space. At a minimum, a consensus has emerged that the force will incorporate space, cyber, and electronic warfare, but the full extent of what this means is unclear. It is also unknown, for instance, if the space mission will include space launch facilities, or whether those will remain under the CMC Equipment Development Department, a rechristened General Armament Department. Where psychological operations will fall in the new order is also up for debate. Some sources have said that it will be incorporated into the SSF while others have left it out entirely.

Finally, although it is clear that the SSF will act as a service, it remains unclear if the CMC will also treat it as an operational entity, or how the CMC will operationalize forces that are under its administrative purview. It is unlikely that the military theaters will have operational authority over strategic-level cyber units, electronic warfare units, or space assets. These capabilities will likely be commanded directly by the CMC. This logic flies in the face of the new system, which requires that services focus on force construction rather than operations and warfare. The solution may be that the SSF, as well as the PLARF, act as both services and “functional” commands for their respective missions.

Conclusion

Ultimately, the strategic support force needs to be understood in the broader context of the reforms responsible for its creation. On one hand, the reforms are practical, intending to usher China’s military forces into the modern era and transform them into a force capable of waging and winning “informatized local wars.” On the other hand, the reforms are politically motivated, intending to reassert party leadership to transform the PLA into a more reliable, effective political instrument.

The Strategic Support Force, if administered correctly, will help solve many of the PLA’s problems that have prevented it from effectively implementing joint operations and information warfare. The creation of an entire military service dedicated to information warfare reaffirms China’s focus on the importance of information in its strategic concepts, but it also reveals the Central Military Commission’s desire to assert more control over these forces as political instruments. With the CMC solidly at the helm, information warfare will likely be leveraged more strategically and will be seen in all aspects of PLA operations both in peace and in war. China is committing itself completely to information warfare, foreign nations should take note and act accordingly.

John Costello is Congressional Innovation Fellow for New American Foundation and a former Research Analyst at Defense Group Inc. He was a member of the U.S. Navy and a DOD Analyst. He specializes in information warfare, electronic warfare and non-kinetic counter-space issues.

Notes

1. A Chinese-media report on Gao Jin’s military service assignments can be found at <http://news.sina.com.cn/c/sz/2016-01-01/doc-ifxneept3519173.shtml>. Gao Jin’s role as commander of the SSF is noteworthy in two respects: One, he is a career Second Artillery officer, so his new role muddies the waters a bit in understanding whether the SSF will be a force composed of Army personnel but treated administratively separate from the Army—not unlike the former PLASAF-PLA Army relationship—or will be composed of personnel from various services and treated administratively separate from all forces. Secondly and more important to this discussion, before his new post as SSF commander, Gao Jin was head of the highly-influential Academy of Military Sciences (AMS) which besides being the PLA’s de facto think-tank (along with the National Defense University), is responsible for putting out the Science of Strategy, a wide-reaching consensus document that both captures and guides PLA strategic thinking at the national level. The most recent edition published in 2013 was released under his tenure as commandant of AMS and many of the ideas from that edition have found their way into the 2015 defense white paper, December’s guide on military reforms, and many of the changes made to China’s national defense establishment. His new role could be seen as CMC-endorsement of SMS’s views on China’s strategic thought.

2. Song’s description of the SSF contradicts official-media descriptions of the service, which had suggested that the service will occupy a similar echelon to that of the PLASAF before it was promoted to full military service status equal to the other branches.

3. Ian M. Easton and L.C. Russell Hsiao, “The Chinese People’s Liberation Army’s Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Project: Organizational Capacities and Operational Capabilities,” 2049 Institute, March 11, 2013. p. 14.

4. The Science of Military Strategy [战略学], 3rd ed., Beijing: Military Science Press, 2013. p. 320.

5. Ibid. p. 165.

6. Ibid. p. 164.

Featured Image: Soldiers of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army 1st Amphibious Mechanized Infantry Division prepare to provide Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Adm. Mike Mullen with a demonstration of their capablities during a visit to the unit in China on July 12, 2011. (DoD photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Chad J. McNeeley/Released)

![Figure 1. The Three Layers of Cyberspace[iii]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/bebber2.png)

![Figure 2. Notional Center of Gravity Analysis[xiii].](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/rsz_image_1.png)