By Alex Crosby

According to Julian Corbett, “[T]he object of naval warfare must always be directly or indirectly either to secure the command of the sea or to prevent the enemy from securing it.”1 However, naval warfare innately favors stronger naval powers in their pursuit of command of the sea. This institutional bias can drive weaker naval powers to act in less traditional manners, with the effects bordering on dangerously destabilizing to the involved security environment. Likewise, weaker naval powers can become increasingly receptive to the establishment of innovative and unique options to achieve the relative parity necessary for contesting command of the sea.

First, weaker naval powers can use asymmetric naval warfare in the form of devastating technologies and surprise shifts in strategy. Second, weaker naval powers can leverage coalitions to increase relative combat power and threaten secondary theaters to diffuse the adversary’s combat power. Finally, weaker naval powers can inflict cumulative attrition along distant sea lines of communication. These options, singularly or together, can enable a weaker naval power to contest command of the sea against a stronger naval power.

Asymmetric Naval Warfare

A weaker naval power can use asymmetric naval warfare to contest the command of the sea through the integration of devastating technologies. For example, during the Russo-Japanese War, the Japanese leveraged two unique warfighting capabilities to undermine relative Russian naval superiority. First, the Japanese Navy used naval mines to offensively damage or destroy Russian ships attempting to leave Port Arthur.2, 3 Additionally, the placement of mines provided a means of sea denial, allowing Japanese ships to contest and control the waters surrounding the Korean Peninsula with limited demand for direct naval engagements.

Second, the Japanese Navy used destroyers armed with torpedoes in close-proximity attacks on the Russian battleships of Port Arthur.4 This asymmetric employment of small naval assets with lethal firepower proved to be a devastating surprise against Russian ships expecting significant force-on-force engagements. This technology combination, mines and torpedo-equipped destroyers, is an example of how a relatively weaker naval force can contest command of the sea, especially in littoral waters.

Another means of asymmetric warfare that a weaker naval power can leverage for contesting command of the sea is a surprise shift in strategy. An example of this is the strategy of unrestricted submarine warfare focused on commerce targets that the German Navy used during the early stages of the Second World War. Early in the conflict, Germany identified the sea lines of communication crossing the Atlantic Ocean from the United States as critical for continued Allied efforts in the European and North African theaters.5 Germany concentrated its well-trained and disciplined submarine force and associated combat power into wolf packs to target this vulnerability. The primary objective of these wolf packs was to attrit as much tonnage of Allied shipping as possible, with the desired effect of exceeding the rate at which the Allies could replace their respective shipping fleets.6, 7 Germany was able to have significant successes during the early stages of the war, particularly by focusing these wolf packs off the east coast of the United States. This placement and intensity of submarine forces instilled a corresponding fear into the American populace and directly contested command of the sea.8, 9

In the early period of the war, the German strategy was definitively effective against the desired target set. Thus, a strategy such as unrestricted submarine warfare can be particularly useful in contesting command of the sea when the adversary is unsensitized to that type of warfare and remains slow in implementing tactics or technology necessary for countering.10 Asymmetric naval warfare, either through the employment of devastating technologies or the employment of surprise strategies, has the potential to be a force multiplier for weaker naval powers in contesting command of the sea.

Leveraging Coalitions

A weaker naval power can further contest command of the sea by leveraging coalitions, mainly through the increase of combat power parity to surpass that of an adversary’s superior naval strength. During the Peloponnesian War, Sparta represented a predominantly land-centric power compared to the naval-centric Athens in a conflict dominated by the maritime domain. Assessing its accurate position as the weaker naval power, Sparta sought allies that possessed naval strength to increase the combined power of the Peloponnesian League to contest Athens’s claim on command of the sea.11 Additionally, Sparta leveraged the Persian willingness to export naval capabilities in exchange for economic and diplomatic trades further to increase the naval strength of the Peloponnesian League.12 The Spartan increase in maritime power through a combination of direct and indirect coalitions had the additional effect of instilling strategic paranoia in Athenian leadership. This fear of Sparta, and more specifically the fear of Sicilian states joining the Peloponnesian League, caused Athens to overextend its naval power for a resource-draining expedition.13 The alignment of combined naval strength against the Delian League ultimately proved decisive for turning the tide of the Peloponnesian War in favor of the Spartan-led coalition.

A weaker naval power can also leverage coalitions, and the increase in combined naval power, to threaten a stronger adversary in secondary theaters and diffuse their combat power to more manageable levels. The American Revolution is an example of this situation, where the American colonies gained the critical maritime support of France. This coalition represented relative combined naval power that exceeded that of the British Navy and continued to increase throughout the remainder of the war.14, 15 Additionally, the France’s colonial garrison forces and associated sea lines of communication in proximity to British global equities diffused British naval power to relatively weaker concentrations.16 This reduction in the British Navy’s ability to mass combat power was further compounded with France’s entry into the conflict. The threat posed by France spurred Britain to allocate significant naval power for the defense of the British Isles from invasion, altering the primary strategic objective of the entire war.17, 18 The combined effort of France and the Thirteen Colonies displayed the importance of several weaker naval powers forming a coalition against a stronger naval power and the strategic dilemma it can manifest for an overextended adversary.

Inflicting Cumulative Attrition Along Distant Sea Lines of Communication

Finally, a weaker naval power can contest command of the sea by inflicting cumulative attrition along distant sea lines of communication. During the Second World War, the Japanese Navy identified the vast distances of the Pacific Ocean as a critical operation factor that presented several advantages to achieving command of the sea. The tyranny of distance associated with any sea lines of communication required by a transiting American force would be vulnerable to Japanese exploitation. Specifically, Japan planned for the expected significant quantities of merchant shipping to be a central target set of its strategy for degrading American naval power to more manageable levels.19 Additionally, the extreme distances of the Pacific Ocean would, at least in the initial stages of the conflict, prevent the American Pacific Fleet from massing to its maximum combat potential. Based on the detriments the distances would inflict on American naval operations, the Japanese aimed to inflict cumulative attrition with a defined strategy.

The Japanese Navy implemented a wait-and-react strategy, which was planned to involve a series of naval engagements far from Japanese centers of gravity to attrite the American Pacific Fleet.20 In addition to these minor naval engagements, the wait-and-react strategy relied upon the garrisoning of island strongholds. These strongholds would allow the concentration of air and naval offensive combat power to attrite a westward-moving American naval force further. The projection of Japanese combat power would have directly threatened the massing of American naval strength, both of warships and the associated merchant shipping.21 Through this added attrition of sea lines of communication, the American naval power was intended to have been decreased to matching or weaker status than the Japanese Navy. This risk reduction would then have enabled a decisive fleet-on-fleet engagement, allowing Japan to gain command of the sea.22 Despite the distances of the Pacific Ocean and its status as a relatively weaker naval power, the Japanese Navy formulated a strategy with the potential to inflict enough cumulative attrition for decisive effects.

An Argument For Joint Force Integration

Some might argue that a better option for a weaker naval power to contest command of the sea would be the integration of the joint force against the threats posed by a stronger naval power. Julian Corbett in particular proclaimed the value of joint integration to achieve maritime objectives such as contesting command of the sea.23 The coordination of joint firepower is critical to mass enough effects to contend with a stronger naval power, which is especially pertinent with the introduction of modern technology.24

Additionally, the influence of devastating offensive firepower, including over the horizon targeting capabilities, validates the insufficiency of mono-domain action from the sea. The combination of a multi-domain aggregation of firepower is a near necessity for a weaker naval power to have any legitimate chance at contesting command of the sea.25

Conclusion

Joint operations, while important in a general sense, and critical for first rate navies, are not the best option for weaker powers to contest command of the sea. Joint operations are resource-intensive and could prove more burdensome than helpful for a weaker naval power. Additionally, joint interoperability would likely be nonetheless reliant on the previous factors of asymmetric naval warfare, coalition leveraging, and attrition of distance sea lines of communication in order to be effective. Conversely, joint interoperability is not a prerequisite for those different factors. Asymmetric naval warfare can be conducted regardless of a joint force in a variety of ways, especially when possessing devastating technologies and employing surprise shifts in strategy that undermine an adversary’s understanding of the maritime environment.

Coalitions can be leveraged to increase relative combat power and threaten an adversary’s secondary theaters without the demand of a joint force. Distant sea lines of communication can be harassed and attacked to inflict cumulative attrition absent a joint force. Even a small, unique advantage has the benefiting possibility of supporting the instillment of innovation and growth towards multilateralism, all caused by existential concerns with the maritime domain.

Ultimately, a weaker naval power has a multitude of options when it comes to contesting command of the sea against a stronger naval power without needed to rely on joint operations.

Lieutenant Commander Alex Crosby, an active duty naval intelligence officer, began his career as a surface warfare officer. His assignments have included the USS Lassen (DDG-82), USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7), U.S. Seventh Fleet, and the Office of Naval Intelligence, with multiple deployments supporting naval expeditionary and special warfare commands. He is a Maritime Advanced Warfighting School graduate and an Intelligence Operations Warfare Tactics Instructor. He has masters’ degrees from the American Military University and the Naval War College.

References

1. Corbett, Julian S. “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy.” London: Longman, Green, 1911. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, reprint, 1988. 62.

2. Mahan, Alfred Thayer. “Retrospect upon the War between Japan and Russia.” In Naval Administration and Warfare. Boston: Little, Brown, 1918. 147

3. Evans, David C. and Mark R. Peattie. “Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941”, Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997. 101.

4. Corbett, “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy,” 149.

5. Matloff, Maurice. “Allied Strategy in Europe, 1939-1945.” In Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Peter Paret, ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. 679.

6. Murray, Williamson and Alan R. Millett. A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000. 236.

7. Baer, George W. “One Hundred Years of Sea Power: The U.S. Navy, 1890-1990”. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1994. 192.

8. Ibid., 194.

9. Cohen, Eliot A. and John Gooch. Military Misfortunes: The Anatomy of Failure in War. Paperback edition. New York: Free Press, 2006. 61-62.

10. Murray and Millett, A War to Be Won: Fighting the Second World War, 250-251.

11. Strassler, Robert B., ed. The Landmark Thucydides. New York: The Free Press, 1996. 1.121.2.

12. Nash, John. “Sea Power in the Peloponnesian War.” Naval War College Review, vol. 71, no.1 (Winter 2018). 129.

13. Strassler, ed. “The Landmark Thucydides,” 6.11.

14. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, 505.

15. O’Shaughnessy, Andrew Jackson. The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013. 343.

16. Mahan, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, 1660-1783, 520.

17. O’Shaughnessy, “The Men Who Lost America: British Leadership, the American Revolution, and the Fate of the Empire,” 14.

18. Mackesy, Piers. “British Strategy in the War of American Independence.” Yale Review, vol. 52 (1963). 555.

19. James, D. Clayton. “American and Japanese Strategies in the Pacific War.” In Makers of Modern Strategy: From Machiavelli to the Nuclear Age. Peter Paret, ed. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986. 717.

20. Evans, David C. and Mark R. Peattie. Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1997. 464.

21. Lee, Bradford A. “A Pivotal Campaign in a Peripheral Theatre: Guadalcanal and World War II in the Pacific.” In Naval Power and Expeditionary Warfare: Peripheral Campaigns and New Theatres of Naval Warfare. Bruce A. Elleman and S. C. M. Paine, eds. London and New York: Routledge, 2011. 84-85.

22. Evans and Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941, 464.

23. Corbett, “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy,” 15.

24. Corbett, Julian S. “Maritime Operations in the Russo-Japanese War, 1904-1905”. Vol. 2. Annapolis and Newport: Naval Institute Press and Naval War College Press, 1994. 382.

25. Evans and Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941, 484.

Featured Image: SOUTH CHINA SEA (April 22, 2023) – F/A-18F Super Hornets from the “Mighty Shrikes” of Strike Fighter Squadron (VFA) 94 fly in formation above the aircraft carrier USS Nimitz (CVN 68). (U.S. Navy photo)

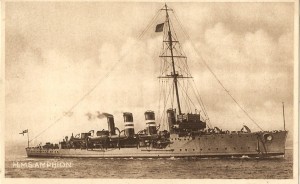

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”