What maritime dispute is most likely to lead to armed conflict in the next 5/10/20 years?

This is the seventh in our series of posts from our Maritime Futures Project. For more information on the contributors, click here. Note: The opinions and views expressed in these posts are those of the authors alone and are presented in their personal capacity. They do not necessarily represent the views of their parent institution U.S. Department of Defense, the U.S. Navy, any other agency, or any other foreign government.

LT Scott Cheney-Peters, USNR:

I’m going to confine my thoughts here to the most likely to spill over into conflict and save the rest for Question 9. I expect that I will of course get most of this wrong. There’s a reason I’m not a betting man.

I’m going to confine my thoughts here to the most likely to spill over into conflict and save the rest for Question 9. I expect that I will of course get most of this wrong. There’s a reason I’m not a betting man.

0-5 Years: As we’ve been arguing on this site since last year, the numerous maritime disputes in which China is involved, China’s seeming unwillingness to seek a diplomatic resolution to these disputes, and China’s unilateral moves to change the situation on the ground (sea) means that there is an alarming risk of miscalculation and escalation in any of a number of conflicts (the Senkakus/Diaoyus; the Spratleys, the Paracels, etc). This is not to lay the blame solely in China’s lap, however. The recent (re-)election of Shinzo Abe in Japan at the head of a nationalist LDP government will perhaps be just as unwilling to make concessions in the Senkakus dispute, for example. And as we saw with the protest voyage to the Senkakus of the Kai Fung No. 2, non-state actors can just as easily force a government’s hand. All of this is despite the incredibly complex and large economic ties which bind all of the participants. Further, there is the possibility in any of these conflicts that a “wag-the-dog” component might come into play as the Chinese, Japanese, or another government seeks to distract from political or economic domestic problems through foreign adventurism.

Speaking of which, my runner-up scenario: Argentina vs the U.K., Round II.

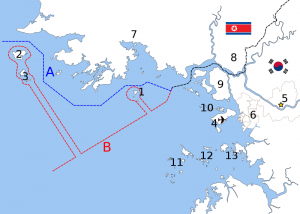

5-10 Years: The collapse of North Korea is something of a continuously looming catastrophe. Any prediction attempting to nail down a date has, of course, thus far been proved wrong. But the likelihood that it will happen at some point and the magnitude of follow-on effects requires robust contingency planning.

The reason I bring it up is that many of these potential follow-on effects dangers involve the possibility of maritime conflict – from a starved North Korea launching a land and sea invasion across the Demilitarized Zone and Northern Limit Line, or a combustible mix of Chinese and South Korean troops flooding into a post-regime North Korea, “disagreeing” over the terms of administration and reconstruction.

In a Naval War College class last year we presented a scenario in which the collapse of the North precipitated a potential humanitarian disaster, prompting a Chinese move across the border to stem the flow and the grave danger of miscalculation leading to conflict between some combination of American, South Korean, Chinese, and ex-regime ground and/or naval forces. We argued contingency planning (and regular multinational Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Response exercises) for such a possibility needed to begin now between the U.S., South Korea, and China. More on this will follow in my oft-delayed post “Thinking About Prevention, Part III.”

Runner-up: Iran – because, well, the IRGCN sometimes seems like it requires individual units to bring foreign vessels to the point of batteries release as part of a bizarre initiation process.

10-20 Years: The long-range forces likeliest to lead to maritime conflict in this timeframe and beyond may be urbanization, bringing more people to the cities, and climate change, bringing the seas closer to the cities. These won’t necessarily lead to a specific conflict, but could create a greater possibility of some new forms (in a tactical sense) of maritime insurgencies or require new/improved abilities to fight in maritime urban environments.

Simon Williams, U.K.:

The disputes raging between China and its South East Asian neighbours over islands and influence in the energy reserve rich South China Sea, I believe, has the greatest potential to escalate into armed conflict with many regional powers flexing their military muscles. The standoff also has the potential to draw in other global powers, with America and India waiting in the wings to defend their interests should they deem it necessary. Moreover, options for a diplomatic solution are slowly contracting; last year ASEAN nations failed to agree on a ‘code on conduct’ at the annual summit meeting. Tensions also have the inherent risk of drawing in other powers due to the globally vital trading routes passing through the region. America has already announced an increased focus on the wider Pacific region, a strategic shift which has caused some chagrin in Beijing, which contends the Americans are interfering and in effect staging an attack on China.

The increasing size of the Indian Navy and the ambitions of China to build a credible fleet, demonstrated by the recent launch of their first aircraft carrier, are likely to lead to a further increase in tensions. History demonstrates that two nation’s with large navies and divergent regional interests rarely get along.

LT Drew Hamblen, USN:

The Senkaku Islands, the Spratlys, or Taiwan itself.

Marc Handelman, U.S.:

Unchecked African-based oceanic piracy.

Polar (Northern) national territorial & natural resource exploitation.

Felix Seidler, seidlers-sicherheitspolitik.net, Germany:

Definitely the South China Sea, not the Persian Gulf. The Iranian naval threat is over-hyped. The U.S. Navy would sink most of Iran’s vessels within a few hours. However, in the South China Sea, the interests of the U.S., China, and India clash. With rising 1) population numbers, 2) regional economies, 3) nationalism/nation self-confidence, 4) resource demand, and 5) Armed Forces capabilities, armed conflict between two or more states is more likely in the South China Sea than anywhere else. These five points create a dangerous cocktail, because any conflict, from whatever cause, could quickly escalate.

Dr. Robert Farley, Professor, University of Kentucky:

I would not be at all surprised to see conflict between China and one or more ASEAN states over island control and access in the South China Sea. The game is extremely complicated, ripe for miscalculation, and prone to a variety of principal-agent problems. States that don’t want to be in an armed dispute could easily find themselves embroiled if they miscalculate the intentions of others.

Bryan McGrath, Director, Delex Consulting, Studies and Analysis:

Cliché, but one of the ongoing South China Sea scenarios seems most likely.

YN2(SW) Michael George, USN:

Within the next 2 decades, the only legitimate threat from a maritime perspective I can foresee is China. From various disputes with Japan to burgeoning naval capabilities, such as its new aircraft carriers, China seems to be a force to be reckoned with.

LCDR Mark Munson, USN:

I don’t see the various disputes that China has with neighbors in the East and South China Seas as being the seeds for future armed conflict. One possibility that could snowball into something worse would be the various Persian Gulf states reacting in response to further efforts by Iran to assert its control over the Straits of Hormuz. My most likely scenario, however, would be a fight between North and South Korea over encroachments across the Northern Limit Line.

Sebastian Bruns, Fellow, Institute for Security, University of Kiel, Germany:

Until 2018: South China Sea; Strait of Hormuz/Persian Gulf.

Until 2023: China’s rise (in general); Northwest & Northeast Passage; South America undersea resources; and/or any of the above.

Until 2033: China’s rise (in general); and/or any of the above.

CDR Chuck Hill, USCG (Ret.):

China and Iran are the most obvious candidates. Today’s Navy seems geared to those threats. Looking elsewhere, we are likely to see some asymmetric conflicts where insurgents attempt to exploit the seas.

China will continue to push its claims in the South and East China Seas by unconventional means, or perhaps we may wake up some morning and find that every tiny islet that remains above water at high tide has been occupied. They are building enough non-navy government vessels to do that. They may also sponsor surrogates to destabilize the Philippines, Indonesia, and other Asian Nations that don’t willingly accept Chinese leadership.

We may also see conflicts:

– in Latin America, e.g. Venezuela vs. Colombia;

– between the countries surrounding the Caspian Sea over oil and gas drilling rights;

– over water resources on the great rivers of Asia.

There are always wars in Africa. They may become more general. Wherever there is both oil and weak governments, there may be conflict – Nigeria and Sudan come to mind. The entire Maghreb is at risk with Libya unstable, an ongoing arms race between Morocco and Algeria, and a growing Al-Qaeda franchise.

Bret Perry, Student, Georgetown University

5 Years: Nigerian Piracy. Although not necessarily a maritime dispute, this is a serious maritime security issue that could get ugly. Piracy is on the rise again in Nigeria but unlike previous periods of piracy in the country the current episode appears less political and more criminal making it more threatening and difficult to combat. Although Nigeria does not see as much commercial shipping traffic as Somalia, it still is a significant oil exporter via sea. This, combined with the increase in offshore oil facilities in the area, make piracy a serious threat to the area.

10 Years: Persian Gulf Conflict. There is so much military activity among multiple countries in this region that conflict is likely. Although the US Navy and IRGCN have both displayed discipline thus far, if either side makes a mistake, or is pushed by another party, then the Gulf could experience some maritime conflict.

20 Years: The South China Sea. Tensions in this region between the different parties involved will continue to fluctuate, but it will be some time until China possesses the confidence to decisively act militarily.

LT Alan Tweedie, USNR:

Both Iran and North Korea are unpredictable enough to start an armed conflict which would spill into the sea. The two also have enough land-based anti-ship cruise missiles (ASCMs) and ballistic missiles to put AEGIS/BMD to work for its intended purpose. India and Pakistan could also heat up their cold war, although I highly doubt the U.S. would get involved militarily in such a dispute.

LT Chris Peters, USN:

5 Years: Iranian maritime claims in conjunction with their nuclear development.

10 Years: North Korea vs South Korea OR China vs Japan re: disputed islands.

20 Years: Access to Arctic waterways and seabed resources.

CDR Chris Rawley, USNR:

I’ll answer this question in the broader context of defense strategy. The U.S. DoD is making a deliberate pivot to East Asia, but changing global demographics don’t necessarily support such a shift. At the Jamestown Foundation’s recent Terrorism Conference, insurgency-expert David Kilcullen spoke to four global trends:

1) Population growth – By 2050, there will be over 9 billion people on earth. Much of this rapid growth will continue in less-developed regions of the world, with the “youth bulge” more prominent in the Middle East and Africa. Meanwhile the populations of industrialized countries, including China, will remain stagnant, or even shrink.

2) Urbanization – The trend of people moving to cities will continue, especially in Africa and South Asia. Urbanization brings with it higher rates of crime, pollution, and sprawling slums. The problems associated with these issues will often spill outside of a city’s borders, sometimes even becoming transnational.

3) Littoralization – Mega-cities (those with more than 10 million people) appear mostly in coastal regions. Poverty-stricken mega-cities in littoral areas such as Mumbai, Karachi, Dhaka, and Lagos are growing the fastest.

4) Connectedness – People and financial sectors are increasingly linked together globally with networks, cell phones, and satellites communications. These technologies provide constant global reach to anyone, anywhere.

The demographic trends are global, but the first three are most pronounced in coastal Africa and the Indian Ocean rim countries. Kilcullen primarily discussed these trends in the context of al Qaeda’s future. As an example, he believes (as do I) we will see more Mumbai-style attacks, with the terrorists infiltrating from the sea and command-and-controlling their operations in real time with smart phones and social media. But these four trends have greater implications for national security than the terror threat alone. Importantly, they indicate that irregular, people-centric threats will continue to create a disproportionate share of crises most likely to precipitate military intervention. It makes sense to array higher-end forces in areas where higher-end, state-centric threats are possible. But before we realign too much force structure to counter a blue-water fight in East Asia, we should consider that the types of missions these ships have been doing in the Indian Ocean and Persian Gulf the past two decades is what they will likely continue to do for the next two decades.

Moreover, the trends revalidate the importance of sea power to our nation’s security and support disproportionate defense spending on the Navy/Marine Corps team. From an acquisition stand-point, the Navy will need more platforms and weapons optimized to operate in the littorals and a continued focus on expeditionary logistics. Doctrinally, the Marine Corps will need to develop and practice new concepts for fighting in urban terrain.

LCDR Joe Baggett, USN:

Melting of the Polar Ice caps – Creating a race for claim and sovereignty over resources. Climate change is gradually opening up the waters of the Arctic, not only to new resource development, but also to new shipping routes that may reshape the global transport system. While these developments offer opportunities for growth, they are potential sources of competition and conflict for access and natural resources.

Increased competition for resources, coupled with scarcity, may encourage nations to exert wider claims of sovereignty over greater expanses of ocean, waterways, and natural resources—potentially resulting in conflict.

LTJG Matt Hipple, USN:

In the specific realm of dispute over the maritime domain, as opposed to just armed conflict in the maritime domain (in which case, Iran), the Senkakus are the most likely candidate. It wouldn’t be a full-blown war, but certainly there is a likelihood of shots being fired in misguided anger or accident with the increased level of friction contact between multiple opposing navies and fanatical civilians.

LT Jake Bebber, USN:

If history teaches us anything, it is that the next major conflict will occur in an area we will not expect and involve parties and issues that will surprise us (how many of us could point out Afghanistan on a map on September 10, 2001?). We will likely not be prepared. That being said, if I had to bet money, I would suggest that the maritime dispute between Japan and China over the Senkaku Islands is the one most likely to lead to a maritime conflict, drawing in a reluctant United States.