A recent sign posted on the window of a Beijing restaurant refuses to serve certain nationalities due to current international maritime disputes between state actors. Sarah Danruo Wang analyzes how historic disputes on sea (and on land) shape national identity

As I near graduation at the University of Toronto, I keep thinking about vignettes of my incredibly awkward, enlightening, and unforgettable first year that really shaped some of my research interests today. In one such episode, as I was researching a paper on the Franco-Prussian War I encountered an odd little anecdote about how, decades back, a group of people watched an opera so cathartic that when it concluded, Belgium was born. Since then I have researched what it means to be “German” through the ambitions of Bismarck; “Soviet Russian” during Lenin’s implementation of national language policies; “Greek” during the fall of Constantinople; “Czechoslovakian” amidst such an unstable geography; and “Azerbaijani” in a seemingly ethnically homogenous, enigmatic Iran. Personally, I was born in Beijing and I have lived for four to five years each in Ottawa, the San Francisco Bay Area, Vancouver, and now Toronto – a mobile life that renders me identity-less. If our characters are formed through our reactions to our struggles, is a national identity similarly (re)created through the interpretation of conflict?

As I near graduation at the University of Toronto, I keep thinking about vignettes of my incredibly awkward, enlightening, and unforgettable first year that really shaped some of my research interests today. In one such episode, as I was researching a paper on the Franco-Prussian War I encountered an odd little anecdote about how, decades back, a group of people watched an opera so cathartic that when it concluded, Belgium was born. Since then I have researched what it means to be “German” through the ambitions of Bismarck; “Soviet Russian” during Lenin’s implementation of national language policies; “Greek” during the fall of Constantinople; “Czechoslovakian” amidst such an unstable geography; and “Azerbaijani” in a seemingly ethnically homogenous, enigmatic Iran. Personally, I was born in Beijing and I have lived for four to five years each in Ottawa, the San Francisco Bay Area, Vancouver, and now Toronto – a mobile life that renders me identity-less. If our characters are formed through our reactions to our struggles, is a national identity similarly (re)created through the interpretation of conflict?

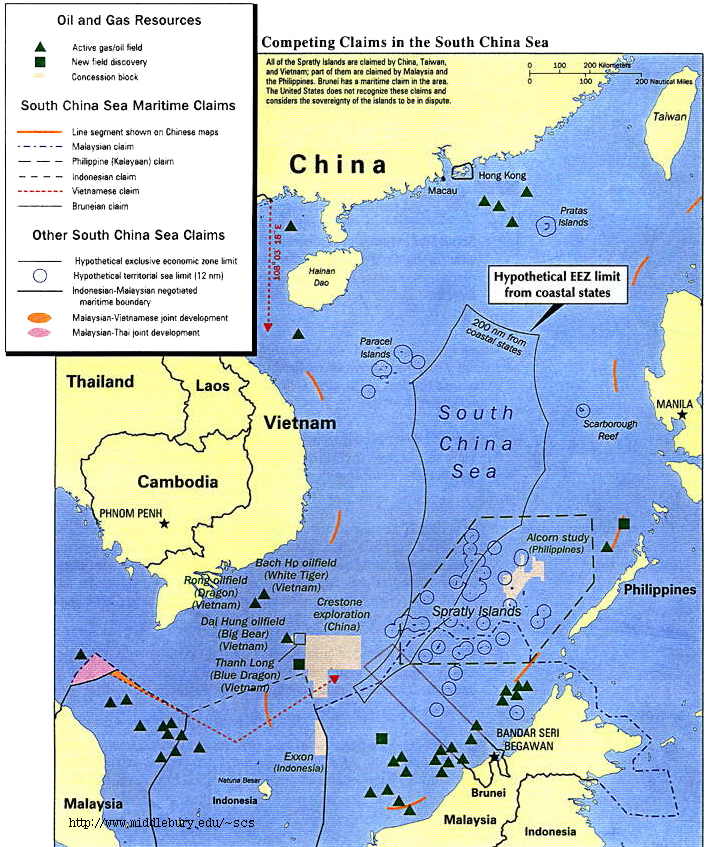

A restaurant in Beijing has a faded sign on its window: “This shop does not receive the Japanese, the Philippines (sic), the Vietnamese, and dog.” I admit that I am not shocked by this almost boastful racism from my hometown. Chinese signs were once the tangible symbols of losing something in translation, yet this one is succinctly clear. Why specifically these three countries? It turns out that each has a maritime dispute with China. China is obviously at odds with Japan over the Senkaku/Diaoyu Islands; and with Vietnam and the Philippines over islands in the South China Sea. Although the sign is an isolated incident, provoking nasty reactions from the nationalities in question, the state has not asked the owner to remove the sign as the owner indicates that “this is my own conduct.” What many news outlets did not mention is that this sign is eerily reminiscent of a well-told Chinese story of a sign reading, “Chinese and Dogs Not Admitted”, in Shanghai’s Huangpu Park in the 1920s. Although Chinese people were barred from entering local parks, the exact wording of any signs is disputed. Nevertheless, the restaurateur’s homage, grafted from previous experiences to today’s prejudices, exhibits the tension between perceived relative statuses.

When I was living in the United States, I recited the pledge of allegiance every day. When I returned to Canada, I did not remember the words to the national anthem, let alone the Royal Anthem that we had to sing on the way out of every assembly. I watched my social studies teacher be the only one in the auditorium refusing to stand for “God Save the Queen” because of an alternate stanza belittling the Scots. The nationalism in my Chinese peers and their parents was diluted at best – cultural detachment and youthful apathy. I want to blame the decreased interest in politics on the events and aftermath of 1989, but I now know better, that it was the decision to prioritize economic opportunity, and the spread of a material culture in my generation.

But with a foreign conflict, specifically one that makes the average Chinese feel cheated over our poignant, invaded past, the Chinese public do not disappoint. A traditional Chinese hero is Zheng He, whom we proudly claimed to have travelled the seas centuries before the Europeans. Yet we rarely note that Zheng is not ethnically Han but of Muslim Hui descent. More recent victories and defeats at sea during the Sino-Japanese conflicts of the late 19th century were captured primarily in the Japanese visual style (see image below).

Since the 1990s, when the nation was once again challenged by non-governmental oversight and the retreat of ideology, China has faced and reacted mostly to land-based or conceptual conflicts. China Can Say No, published in 1996, rejected Americanization of culture. The bombing of the Chinese Embassy in Belgrade in 1999 by NATO produced protests that were verbally supported by Vice-president Hu Jintao. The 2008 Summer Olympics was a triumphant display of cohesion and unity. And now, the historical antagonism with Japan is suddenly reignited over rocks. Is this solidarity perhaps just a defense mechanism to perceived (cultural or national) insecurity, rooted in a historical perspective of either relative inferiority or regional supremacy? Or perhaps, it is just a bit more comforting to confront the other in the company of one’s peers?

As for Canada, the Rush-Bagot Treaty of 1818 demilitarized the Great Lakes region by permitting only one naval vessel each for Britain and the United States on Lake Ontario. This demilitarization was seen as a first step testing the precarious trust after the War of 1812. Furthermore, the Naval Service Act of 1910 created the Canadian Navy with second-hand British vessels, the HMCS Niobe and HMCS Rainbow, and established the Naval College in Halifax. Opponents derided the effort, calling the formation the “tin-pot Navy”. Yet this was a clear assertion of Canada’s self-protection autonomy – separate from, but loyal to the Commonwealth.

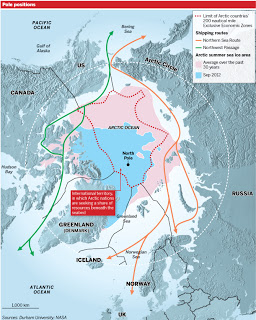

Canada’s maritime security hasn’t always been life-or-death serious. In 2002, Denmark erected a flag and left some Danish vodka on Hans Island in a bizarre attempt to provoke a reaction over a rock that burdens Canadian-Danish relations. Five years later, Russia similarly planted a flag in the seabed of the Arctic to prove “the Arctic is Russian,” illustrating that Russian cooperation and aggression will perpetually be a mercurial cycle. Current maritime concerns in the Arctic revolve around Canada’s ability to react to potential oil spills and pollution through drilling and shipping, and Ottawa’s assistance to indigenous maritime development.

I do not want to poeticize maritime divides, but any fifth grade geography class reveals that the continents were once fitted together like a finished puzzle known as Pangaea. It is appropriate that with continental drift, distance produced distinct people. Only with the advances of maritime technology, ambition, and the lust for adventure led to the discovery of the New World. Shipping and maritime security determined wealth and relative power, which enabled the early flourishing of The Netherlands and divorced England from the European continent.

Before man conquered the skies, maritime passages were the medium for the arrival of the other. It is ironic that for all the efforts China used to build a wall to keep barbarians on horses out, it was defeated by other barbarians on ships at its ports.

The dividing seas also facilitated asymmetric development, ideological escape, and the spread of commerce. The Austro-Hungarian Empire’s lack of a navy exacerbated its economic stagnation as it steadily lost its maritime-efficient proxies through successions or independence. A century later, a Russian ambassador asked why the Czechs needed a navy when the country was obviously landlocked (the Czech representative replied that he did not understand why Russians needed a ministry of cultural affairs). Lastly, incidents like the Komagata Maru and Pearl Harbor shape our collective sense of how national and human security is simultaneously enhanced and endangered by the oceans, as trouble can be carried on the tides.

The racist sign in the Chinese restaurant, among the vast stimuli of a city like Beijing, indicates how disputes trickle down to even the obscurest of places. Conflict on the seas – both today’s and from times past – shapes who we are, what we fear, and how we react.

Sarah Danruo Wang is currently a third year undergraduate student at the University of Toronto studying international relations, philosophy, and fine art history. Her research interests from first year has steadily moved east from Germany to the former Czechoslovakia to Russia and include broader issues in identity politics, EU and NATO eastward enlargement, and education policy. She has previously researched for the Advocacy Project, the Department of History at the University of Toronto, and the G8 Research Group.

This article was re-published by permission and appeared in original form at The Atlantic Council of Canada.