By Charles P. (Chuck) Ridgway, Jr.

In 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan called the Black Sea a “Russian Lake” and encouraged NATO to do more to counter Russia’s efforts to exert control over it.1 Never was that control shown to be more complete than last August, when the Russian Federation Navy stopped and boarded Palau-flagged freighter Şükrü Okan in the southwest portion of the Black Sea, about as far from the Russian coast as you can get, delaying its journey and menacing its crew at gunpoint before determining that it was not carrying contraband and allowing it to proceed. This incident may be seen as the canary in the coalmine indicating imminent suffocation of freedom of navigation in the Black Sea.

The Need for Sea Control

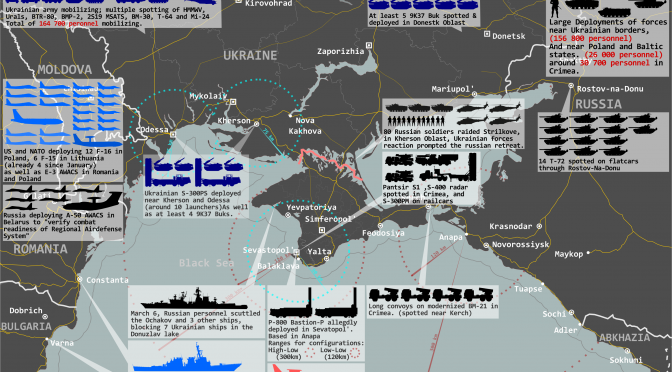

Much has been made of Ukraine’s successful and impressive efforts at sea denial, forcing the Russian Black Sea Fleet to stay well out of coastal missile range and even destroying major units in their homeports as well as at sea. But in what is quite obviously a largely maritime war,2 Russia appears to be achieving its strategic aims despite these tactical setbacks. The Sea of Azov is completely controlled by Russia and a look at MarineTraffic shows that few vessels dare come within 100 nm of Odessa. While the boarding cannot be said to have taken place as part of a blockade, since Russia has not formally declared a blockade, only issued various warning areas3 and vague threats about targeting ships across the Black Sea,4 and is not attempting to enforce a blockade in the manner prescribed by international law, it is telling that the boarding took place where it did, putting the world on notice that ships anywhere in the Black Sea even vaguely suspected of heading towards Ukraine may be boarded, and possibly seized or sunk. While at the same time, President Putin protests when a US warship calls at Istanbul.5 For all intents and purposes, there exists a de facto long-distance blockade, for no other word adequately describes what Russia is doing in the Black Sea. This blockade’s legality may be questionable at best,6 but its effectiveness cannot be doubted. NATO nations, as well as the rest of the world interested in freedom of navigation—including, seemingly, Palau—are doing little to challenge this situation, effectively ceding the maritime domain of the Black Sea to Russia’s bullying and bluster. It seems the Black Sea has indeed become a Russian lake.

The international law of naval warfare covering belligerent interference with merchant shipping, such as blockades and the prevention of the carrying of war contraband, has always represented a compromise between the objectives of the belligerent and the harm neutrals are willing to absorb in losing a certain amount of freedom of navigation.7 The US Military Academy’s Lieber Institute for Law and Warfare has pointed out that the boarding of the Şükrü Okan was legal under “Belligerent Right of Visit and Search.”8 On the other hand, Russia is a signatory to UNCLOS and there are no circumstances permitted by UNCLOS where this boarding could be said to fall under the right of visit of warships. In boarding Şükrü Okan, the Russian navy clearly violated the terms of UNLCOS to which it is bound.

Admittedly, UNLCOS does not address any aspect of naval conflict. But can interference with freedom of the seas be considered legal when the war under which the boarding was conducted is both undeclared and itself illegal? Does UNCLOS cease to apply because one signatory decides to lay mines or stop by force another country’s merchant ships? Are neutral nations willing to accept that UNCLOS can be suspended unilaterally and without formal warning? Most countries, especially those that adhere to the principle of Qualified Neutrality,9 should tend to think not. If the world stands by and does nothing, then Russia’s actions become the new status quo, UNCLOS loses much of its meaning, and the Black Sea—along with any other maritime region where the world persistently acquiesces in the face of aggression—risks losing its status as an international body of water.

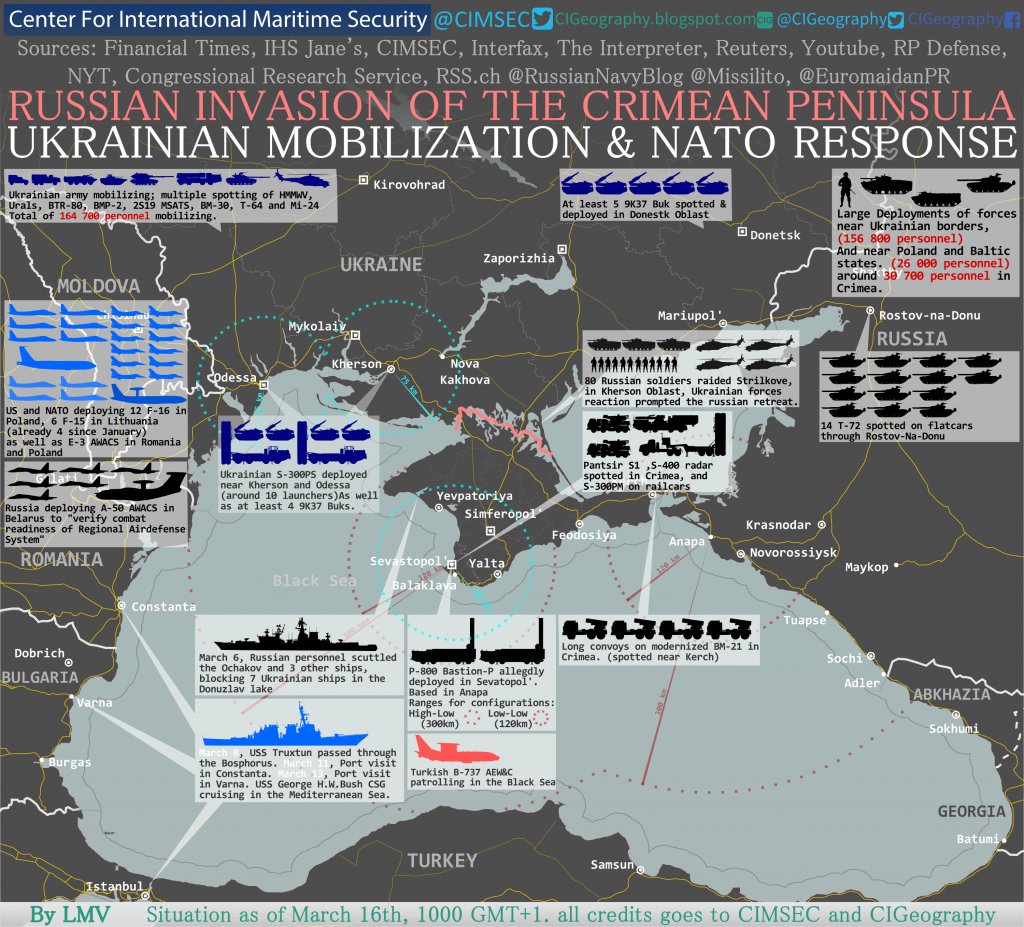

With the collapse of the Black Sea Grain Initiative last summer, Ukraine created the “Ukraine Humanitarian Grain Corridor” by which ships transit through the territorial waters of Bulgaria and Romania, and mainly use Ukrainian ports on the Danube to load grain. The corridor has allowed a certain number of ships to carry grain out of the Black Sea over the past few months,10 though questions remain about the sustainability of insurance costs, especially after a Liberian-flagged vessel was hit by a Russian missile in Odessa on November 9, 2023.11

While Ukraine’s national bank has recently brokered a deal through Lloyd’s of London and other insurers to cut costs12 and many are calling the corridor successful, reports indicate that the grain exported is just a fraction of pre-war quantities: 700,000 tons from August to the end of October versus around 6 million tons a month before the Russian invasion.13 By December, a total of 200 ships had used the corridor carrying an estimated 5 millions tons of agricultural product14 — still well short of prewar levels. From a more strategic viewpoint, the fact remains that in order to export even this amount of grain, merchant ships must hug NATO nations’ coasts, reinforcing the point that the international waters of this part of the Black Sea are not open to shipping. If the shipping industry is unwilling to use the international route, can it still be considered international?

This situation brings up two interesting and related questions: What can be learned from this? And, what can be done about it?

Some Notable Lessons

The first thing that becomes apparent is that sea denial is insufficient when a country depends on open sea-lanes for its basic economic livelihood. While nearly all nations are dependent on the sea for their economic wellbeing, Ukraine’s dependence is stronger than most. A significant portion of its economy rides on its ability to export its grain. And the only efficient, indeed feasible, way to export the majority of it is by ocean-going cargo vessels transiting the Black Sea.

Ukraine’s sea denial efforts offer no help in escorting these vessels or otherwise reducing the perceived risk and, in some ways have enhanced it. Pushing the Russian Black Sea Fleet out of the immediate environs of the Ukrainian coast has had the odd effect of causing Russia’s blockade to expand from a close blockade to one that covers essentially the entire Black Sea minus the territorial waters of the three NATO nations there. And laying defensive mines might have prevented a Russian amphibious assault on Odessa, but has added to the perceived risk to shipping while also allowing political cover for Russia to lay its own mines.

Second, a flag of convenience is no more than that: convenient, until it no longer is. After the Şükrü Okan incident in August, Türkiye waited several days before issuing a warning to Moscow about the boarding of the Turkish-owned and operated ship, with President Erdoğan stating that it was a matter for the flag state.15 An important duty of a flag state is to provide security to vessels on its registry and represent vessel owners’ interests in freedom of the seas on the international stage. Except for a few brief and very localized exceptions, this has not been an important consideration since the end of World War II, though Houthi actions in the southern Red Sea seem to be changing this calculus. None of the world’s leading flag states of convenience—not Liberia, Panama, Marshall Islands, or even Malta—are in much of a position to actively defend their merchant vessels, or even to apply any meaningful diplomatic pressure on a state aggressor as Russia has become in the Black Sea. It is not likely that President Putin will bat an eye at a protest filed by Palau in either the International Maritime Organization (IMO) or UN General Assembly. It is equally unlikely that the Russian Federation Navy would have chosen to board a ship flagged to a NATO member nation or, say, China at this stage of the conflict. Since vessel owners and operators, like the Turkish owners of the Şükrü Okan, cannot count on the support of their own governments when they choose a flag of convenience, it will be interesting to see if they, as the conflict at sea continues, or even expands, reconsider their choice of flag, perhaps preferring one with the naval and diplomatic might to protect their ships.

Third, a blockade no longer requires “effective enforcement”16 to be effective. Apparently, a single boarding, in which the boarded vessel was allowed to proceed, coupled with a few floating mines, is enough to warn off other neutral ships from heading to Ukraine, thereby allowing Russia’s “distant blockade” to expand across the entire Black Sea even while much of the Black Sea Fleet is now holed up in Novorossiysk. It may be a “paper blockade” but that seems to be enough in this conflict.

Fourth, the reason such limited means can produce so effective a blockade is that insurance considerations drive risk assessments in shipping. This is especially true in the Black Sea. Increased war risk premiums during the heyday of Somali piracy did not greatly affect traffic through the Gulf of Aden for a variety of reasons, mainly that relatively few ships of the total traffic through the area were actually attacked and there was no economically alternative route. Instead, the shipping industry and the international community adapted their behavior to increase security and deter attacks. During World War II, though merchant crews obviously faced great physical risk, governments assumed almost all the financial risk for ship and cargo loss (many of the ships and most of the cargo being government owned). The calculus appears to be different in the Black Sea: shipping grain does not offer a profit substantial enough to offset the war risk costs, maritime trade union concerns, and potential losses to either seizure or sinking. Merchant ship operators will begin carrying large quantities of Ukrainian grain when it again becomes profitable.

Finally, the key to pushing Russian control of the Black Sea back towards the Russian coast lies with Türkiye. In the first place, Türkiye is a naval power in its own right and, should it come to it, is fully capable of taking on the Russian Black Sea fleet on more than equal terms. The Turkish fleet is in the best position to reassert control over, at the very least, the southern Black Sea including, for lack of a better demarcation, Türkiye’s EEZ17, and it is Türkiye, as a maritime nation, that has the greatest direct interest in doing so. Second, Türkiye’s control of the entrance to the Black Sea makes it the most important partner for those nations who wish to increase non-Black Sea naval presence there. In recognizing this, one must also recognize that the Montreux Convention, as it currently stands, serves Türkiye’s interests and Türkiye is unlikely to want to renegotiate it: any actions by non-Black Sea states will have to be in accordance with Montreux. Third, Türkiye, more than any other NATO Nation, has both working diplomatic relationships and economic ties (such as TURKSTREAM) with Russia that could allow for useful dialog with respect to Black Sea maritime control but which could also complicate such dialog.

The Way Ahead

Is there anything to be done about this situation? A variety of suggestions have been made, from establishing convoys of merchants ships through the blockade—and mine-infested—zone escorted by NATO’s Standing Naval Forces, to getting Russia to end the conflict. The former suggestion was soundly refuted by RUSI18 on the grounds that the economic/insurance considerations, the Montreux convention, and the nature of the current threat would make such escort impracticable to maintain and not very effective; the latter is clearly a pipedream—until Russia is ready to end the conflict, whether because Russia has achieved all its aims or because it has been defeated, the conflict will go on. So the question really becomes, what constraints is the rest of the world willing to accept on freedom of navigation in the Black Sea and what can they do to push back against the ones they don’t accept.

Here are some practical suggestions, arranged more or less from least to most provocative to Russia, and thereby in order of what would take the most backbone to implement.

First, improve maritime domain awareness (MDA) of the region. A September symposium in Greece highlighted the deficiencies in Black Sea MDA.19 While it is highly probable that no Russian surface ship or submarine of the Baltic fleet gets underway without being actively tracked by one or more NATO nations, and the same is likely true in most cases for the Northern fleet, this probably cannot be said for Black Sea assets. When a Black Sea Fleet Kilo-class submarine leaves Sevastopol and submerges, it is most likely immediately lost to sight until it returns. Improved MDA would allow for greater analysis of trends and recognition of changes in the situation sooner, such as new threats (recently laid mines) or evolution of broader diplomatic conditions (e.g. identifying what changed to make Russia no longer want to participate in the grain deal). It would also allow for better enforcement of sanctions on Russian oil, tracking of individuals of interest, and detection of Russian gray zone maritime operations.

Second, maritime air patrol should be enhanced. There is a significant shortfall of MPA assets and actual patrols over the Black Sea. Of the NATO Black Sea nations, only Türkiye has an MPA component. NATO AWACS aircraft have been reported operating over Poland along the Ukrainian border but not over the Black Sea. There is also reporting that US MPA aircraft are conducting missions over the Black Sea, but it is not clear with whom the information gathered is being shared.20 More MPA coverage would contribute to freedom of navigation, enhanced MDA, intelligence collection, and order of battle development.

Third, governments interested in supporting Ukraine’s ability to export grain should subsidize war risk costs. While subsidies to shipping to offset increased insurance and other war risk costs would not reduce the physical risk to crews or ships, they could make the carrying of Ukrainian grain more attractive. With the end of the Black Sea Grain Initiative, Ukraine began offering subsidies for this purpose but it remains to be seen if this, combined with the new Lloyd’s deal, will be enough to offset costs adequately or if it will be financially sustainable for Ukraine or the insurers over the long term.21

Fourth, ship owners should consider reflagging their grain ships to registries that can offer naval protection and diplomatic gravitas. Palau, like Liberia or Panama, may not be in a position to impede Russian interference with ships of their registry, but all NATO nations are. Russia would need to be willing to risk significant escalation if it wanted to board, say, a German-flagged bulk carrier 30 miles out from the Istanbul Straight. It is not necessary to escort merchant ships—and probably not particularly effective as long as the main threat remains mines22—when the flag carries the weight of Article V with it. It may even be worth considering employing (appropriately-flagged) government-owned ships in the trade, which could also contribute to avoiding war risk costs.

Ship operators should harden merchant ships to prevent boardings. The world’s maritime polity learned a great deal about preventing boardings during the days of Somali piracy and many of the steps developed under “Best Management Practices”23 would serve equally well in repelling unwanted boardings in the Black Sea. Shipping operators or flag states may even wish to embark security teams, generally considered the most effective means at preventing piracy attacks. It is highly unlikely ship owners would choose to do this, but the possibility that a boarding could be opposed would force Russia to determine how far they want to go the next time they attempt a boarding. Is the Russian Navy really willing to sink a neutral flagged merchant ship with naval gunfire?

Navies should be conducting freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in the Black Sea. Neutral nation warships, and especially NATO Nation warships, whether under NATO or national operational control, should be operating and patrolling in all the international waters of the Black Sea. There is no legal or diplomatic reason why a group of neutral frigates should not be conducting routine exercises 20 nautical miles off Novorossiysk or shadowing every Russian Federation Navy ship that leaves Russian territorial waters. While the three Black Sea NATO nations are fully capable of this,24 the diplomatic effect would be greater if there were non-Black Sea-based ships involved, even if just a token and occasional involvement. Diplomatic work with Türkiye should focus on allowing non-belligerent warships into the Black Sea in accordance with Montreux for this purpose. FONOPS is a much better use of surface assets than convoy escort given current conditions in the Black Sea. Aircraft can do FONOPS too.

And, obviously something will need to be done about mines. The recent agreement among the Bulgaria, Romania, and Türkiye to create a mine-countermeasures task group is welcome news on this front.25

Many would argue that these steps are provocative and risk escalating the conflict in Ukraine.26 No one wants a World War III, but the simple fact is that it is up to Russia whether or not to start one by firing on NATO warships, or NATO nation-flagged merchant vessels. Excessive worry about provocation should not hinder warships of neutral or non-belligerent nations from operating wherever in international waters their governments should wish or from ensuring the free flow of goods to the world’s markets in accordance with established international law. Operating in international waters is no more an act of aggression than it is to walk down a dangerous alley at night ready for the worst. Such operations may well complicate operational freedom of movement and rules of engagement for the Russian Black Sea Fleet, for surely they wish to avoid unintended escalation as well, but not conducting them simply makes it excessively easy for Russia not to have to account for such possibilities in planning and executing its naval operations. And there is no reason to make it easy for Russia—especially when doing so cedes effective control over this important maritime space and hurts the world’s economy.

But principle is an even stronger argument for wresting back maritime dominance in the Black Sea from Russia: the principle of freedom of the seas, of the free flow of goods, and of the schoolyard principle that a bully shouldn’t be allowed to get away with it. And, of course, the principle of sea power. Every violation of UNCLOS, every loss of international access to any body of water, every impediment by force of arms to free trade hurts the sovereignty of other nations and chips away at the post-war international order that benefits the free countries of the world. The reason navies exist is to keep the seas open for the benefit of their citizens, but navies have to be willing to go into harm’s way to do so. For all of history, from the Peloponnesian War, through both world wars, to the Falklands conflict, war has been decided by sea power. The Ukraine War is no different. Russia appears to recognize this. Will the rest of the world?

Chuck Ridgway is a retired US Navy surface warfare and reserve Africa foreign area officer. After leaving active duty, he worked for ten years as a NATO international civilian at the NATO Joint Analysis and Lessons Learned Centre in Portugal. Since then he has consulted with a variety of organizations, including One Earth Future Foundation’s Oceans Beyond Piracy and Stable Seas programs, the United Nation Office of Drugs and Crime’s Global Maritime Crime Program, and the US Defense Security Cooperation Agency’s Institute for Security Governance. A native of Colorado, he lives in Denver. This is his first piece for CIMSEC.

References

1. https://eurasianet.org/erdogan-plea-nato-says-black-sea-has-become-russian-lake

2. Midrats Podcast, Episode 662: Grain, Oil and the Unfreeing of the Seas, 23 July 2023

3. https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/news_217835.htm

6. See Fraunces, M. G. (1992). The International Law of Blockade: New Guiding Principles in Contemporary State Practice. The Yale Law Journal, 101(4), 893–918, and https://lieber.westpoint.edu/russia-ukraine-war-naval-blockades-visit-search-targeting-war-sustaining-objects/ for discussions of the legal principles of modern blockades and an interpretation of Russia’s blockade of Ukraine.

7. It is debatable if NATO Nations can be considered strictly neutral in the Ukraine conflict, given that nearly all of them are providing war material to one of the belligerents.

9. Commander’s Handbook on the Law of the Sea, § 7.2.1 (https://usnwc.libguides.com/ld.php?content_id=66281931)

11. https://apnews.com/article/russia-ukraine-war-freighter-odesa-9f87d96cc6064094463fd2ecb0828b36

15. https://www.arabnews.com/node/2356936/middle-east and https://turkishminute.com/2023/08/18/analysis-putin-navigated-dangerous-water-test-turkey-red-line/

16. Fraunces, M. G. (1992), page 897.

17. https://www.un.org/depts/los/LEGISLATIONANDTREATIES/PDFFILES/TREATIES/RUS-TUR1987EZ.PDF

20. US Navy P-8As are evidently “providing security” to vessels using the Ukraine Grain Corridor (https://www.i24news.tv/en/news/ukraine-conflict/1690835345-ship-sailing-from-israel-becomes-the-first-to-break-russia-s-grain-blockade) and there is reporting that they have also provided targeting information to Ukrainian forces (https://news.usni.org/2022/05/05/warship-moskva-was-blind-to-ukrainian-missile-attack-analysis-shows)

21. UATV Report: “Russia’s Grain Manipulations Failed: Ukraine’s Grain Corridor Resumed Operating Despite Threat”; https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YLY9-k96CuU

22. If Kalibr missiles start flying into the sides of merchant ships at sea, the need for escorts obviously changes, as would many other aspects of this conflict.

24. Information on where the Turkish Navy operates, in what strength, and if these patrols contribute to NATO-wide MDA, intelligence collection or deterrence is not publicly available.

25. https://www.tagesschau.de/ausland/europa/seeminen-schwarzes-meer-100.html

26. Some, but not all, of these steps may be included in the U.S. State Department’s work on a Black Sea security strategy. For example, in testimony before the U.S. Senate Subcommittee on Europe and Regional Security Cooperation, James O’Brien, U.S. Assistant Secretary, European and Eurasian Affairs, stated that enhanced maritime air patrol had not been considered (https://www.foreign.senate.gov/hearings/assessing-the-department-of-states-strategy-for-security-in-the-black-sea-region). Publicly available information on this strategy and other efforts directed by the Black Sea Security Act (2024 U.S. National Defense Authorization Act § 1247) is still too vague to allow speculation on what specific actions could be taken.