This article originally appeared in Strategic Vision for Taiwan Security and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By David Andre

Reacting to Australia’s Foreign Policy White Paper, a Chinese Defense ministry spokesperson cautioned Australia to get rid of its “old mentality in mind while having a new Asia Pacific in sight.” While these comments rank as some of the most benign in a recent series of caustic remarks, they do capture the essence of the maritime environment of South and East Asia: A boiling pot where competing historical narratives, rapidly changing geopolitics, and great power competition clash in the East and South China Seas. As these issues are unprecedented, so too are the challenges they present. Too often, though, Australia’s policies have been characterized as a choice between the United States and China, but such a characterization is misleading and oversimplified. One thing is certain: Australia’s maritime policies in South and East Asia will have a significant impact on the countries of the Pacific region.

In November 2017, the Australian government of Malcolm Turnbull released its new Foreign Policy White Paper—the first since 2003. This document describes a very different Asia-Pacific region than the one of 14 years ago, detailing a region where economic dynamism, great-power competition, and land and maritime border disputes are on the uptick. What appears from the White Paper is a resolute Australia, committed to stepping up its role in the security and prosperity of the Pacific. Nowhere is this resolve more salient than in the maritime domain, where disputed islands and maritime militarization threaten to undermine maritime security, destabilize the region, and create a polarized Pacific defined by the divergent security interests of the United States and the People’s Republic of China (PRC). This scenario is routinely presented as a Sophie’s Choice for the Australian government: a choice between the security brought by the United States—Australia’s strongest ally—and the economic prosperity promised by continued trade and investment in China—now Australia’s biggest trading partner. This is a specious argument.

State of Polarization

The argument oversimplifies what is a much more nuanced situation and neglects the fact that Australia has already chosen a side. Though that choice was never between the United States and China; rather it was a choice in favor of a maritime security environment defined by multilateral institutions and a rules-based global order, which neither the United States nor China distinctly embodies. Characterizing Australia’s maritime policies in Asia as anything else is an attempt to force a state of polarization in the region.

The Asia-Pacific is a maritime domain of competing realities and compelling narratives. In the 2017 Foreign Policy White Paper, Australia offered a practical rendering of the geopolitical realities that define the Asia-Pacific. This rendering begins by acknowledging that the maritime superiority long enjoyed by the United States in the Pacific is now being contested by the PRC. Indeed, political, material, and budgetary constraints have placed and will continue to place a significant strain on US naval operations in the Pacific. This contrasts with China, where Xi Jinping holds an extraordinarily powerful position and possesses an economy to support his aggressive military modernization program. Certainly these realities have emboldened China, exemplified by Xi Jinping’s recent Party Congress speech, in which he referenced the construction progress China has made on the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, saying, “no one should expect China to swallow anything that undermines its interests.”

The relevance of these trends to Australia’s security and prosperity is undeniable. So, it should come as no surprise then that the Foreign Policy White Paper states that Australia must step up its efforts in the Asia-Pacific, specifically in regard to the maritime disputes in the South China Sea.

Enduring Allies

For Australia, there are geopolitical realities and historical narratives that impact its maritime policy in the Pacific. Foremost is the reality that the trajectories of China and the United States will continue toward increased competition and, potentially, direct conflict. Putting the debate over hegemonic aspirations aside, China is the most dominant regional power in East Asia and, by extension, the East and South China Seas. Little about this trajectory suggests that there will be a change in the coming decades.

Political climate notwithstanding, the United States and Australia are enduring allies, with a 2017 Lowy institute poll reporting a majority of Australians believe an alliance with the United States remains critical for security — again there is little to suggest that this will change. These trajectories intersect on the regional fault line of the South China Sea and put considerable pressure on Australia.

Second, each country believes it is executing a rational strategy and so has no impetus to change. These rationales derive from deep-seated historical narratives. China believes that the post-WWII global order and the accompanying international norms developed independent of Asian input, and are thus not binding. This leads to a modernizing China that is looking to cast itself as a sidelined power merely assuming its rightful mantle. While there is some validity to this reasoning, there is a counter opinion that purports that the global order, regardless of its Western-centric origins, has allowed China to become the leading economic and military power in Asia. This explains the United States portraying itself as a stabilizing influence and champion of a rules-based international order. As with most national narratives, there is a pragmatic mixture of truth and revisionism involved. Alas, the naval strategies at play in the Pacific are a result of these beliefs and it is unlikely that Australia will change the mindset of either actor. Given this scenario, Australia’s balanced approach remains the best course of action for realizing its interests and the interests of others.

A Third Choice

Portraying Australia’s Asian maritime policies as a choice between the security of the United States and the prosperity of China presents a false dilemma. Australia denounces such depictions, believing that an either/or characterization belies the complexity of Asia’s maritime issues. Unfortunately, such portrayals are common. In 2010, political scientist John Mearsheimer argued that it was inevitable that China’s rise would be seen as offensive in nature and that Australia would have no choice but to join the US-led balancing act.

More recently, in August 2016, a US military official offered a similar sentiment stating that “there’s going to have to be a decision as to which one [China or the United States] is more of a vital national interest for Australia.” With the recent release of the Foreign Policy White Paper, these calls have renewed in earnest, repeated to the point of cliché. Unfortunately, by presenting a polarized view of the maritime domain, these assertions neglect a third choice — the choice of global order and international norms, which supports Australia’s national security better than either of the national strategies of the United States or China.

Australia’s behavior represents a commitment to a multilateral Asia. A member and advocate of multilateral institutions throughout the Asia-Pacific, Australia maintains strong bilateral ties with many members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, (ASEAN), as well as rising powers India and Japan. While many write this off as the lot of a benign Middle Power, it comes with the power to tip the scales.

Proof of this power was on display in China’s reaction to the new Foreign Policy White Paper. Despite its oblique references to maritime disputes, China’s Foreign Ministry was quick to chide Australia for what it called “irresponsible commentary” and “propaganda.” Branding Australia’s foreign policy in such a manner represents China’s own coercive way of telling Australia that it must choose sides. It is also a harbinger of the difficulties that Australia will face as it attempts to navigate an increasingly unstable Asia.

Insistent Tone

While Australia’s tone may be growing sterner under the Turnbull administration, the message is the same: respect the international norms and rules- based global order. In maritime Asia, this means allowing the free flow of shipping through the East and South China seas. The message was present in the 2016 Defence White Paper, with calls to establish a Code of Conduct between China and ASEAN, to stop land reclamation, and uphold maritime rights in accordance with the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Meanwhile, the increased military spending outlined in the Defence White Paper signaled a more insistent tone emerging in Australia’s Foreign policy. Australia struck a similar tone in July 2016, when reacting to the South China Sea arbitration, which ruled in favor of the Philippines.

Alongside these declarations are a series of practical, balanced statements representative of Australia’s position in the regional power dynamics. Julie Bishop’s statements in October 2016 asserting that Australia should seek to de-escalate tensions in the Pacific and not take sides exemplify this sentiment. The continual efforts to goad Australia into choosing sides disrespects Canberra’s strategy and risks removing an important actor’s ability to maintain balance in the Pacific. For just as Beijing’s vision of its regional role continues to expand, so too must Australia’s.

Though Australia has yet to conduct any Freedom of Navigation Operations (FONOP), like the United States has consistently done, the Royal Australian Navy’s presence has been steadily increasing in the region. Indo-Pacific Endeavour, Australia’s largest joint task group to sail in the Indo-Pacific region in 40 years puts action to the words detailed in the foreign policy document. The 11-week long deployment involved ASEAN partners Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand, as well as regional actors such as Japan, India, Micronesia, and East Timor.

Fundamental to Peace

As Australia’s physical role expands, so too does its affirmation of international order. Speaking about Indo-Pacific Endeavor, Minister of Defense Marise Payne referenced the ongoing disputes, saying, “Maintaining the rule of law and respecting the sovereignty of nations large and small is fundamental to continued peace and stability in our region.” In addition to Indo-Pacific Endeavour, Australia participated in a joint exercise with the United States and South Korea in November 2017. These exercises came on the heels of an agreement on joint maritime patrols with the Philippines in Western Mindanao.

In addition to conducting joint maritime operations throughout the region, Australia has steadily increased defense dialogues among ASEAN countries. In early November 2017, Australia concluded the first iteration of a new defense dialogue with Vietnam, which builds on increasingly stronger defense ties that have been building for a decade. There is also a deepening of the maritime relationship with Indonesia, Australia’s nearest ASEAN partner and a unique actor in the South China Sea disputes. In perhaps its most concrete act, Australia routinely conducts Maritime Patrols to contest China’s attempt to establish an Air Identification Zone (ADIZ) over the South China Sea. Lastly, the September 2017 commissioning of the HMAS Hobart signaled the entry of a new class of Destroyers to support the intent of stepping-up engagement in the Pacific.

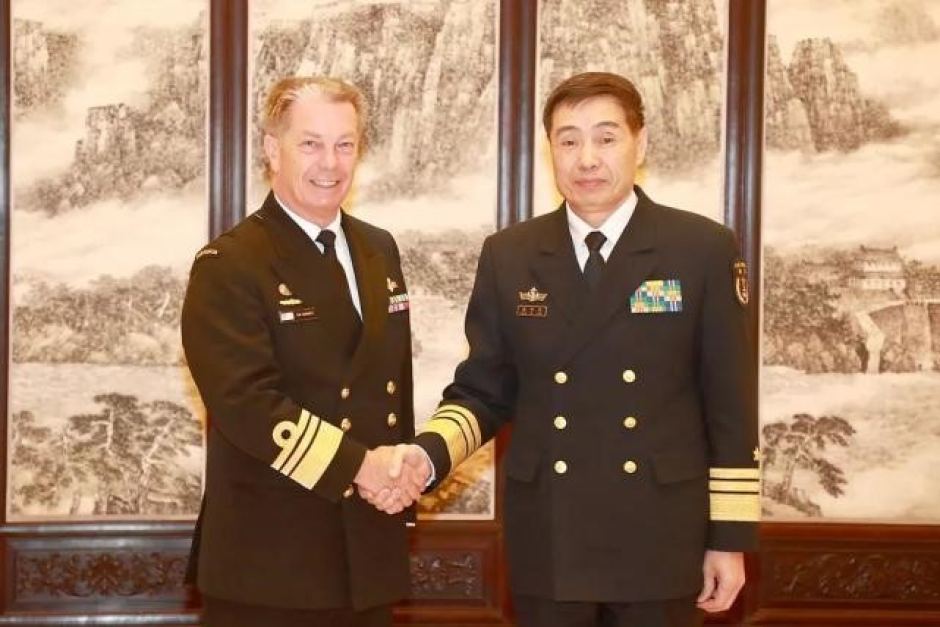

Australia’s steady expansion of its maritime role in the Asia-Pacific still allows room for engagement with China. In August 2017, Australia and China concluded the 20th iteration of their annual Defense Strategic Dialogue in Canberra. The dialogue acknowledged the importance of regional peace and stability in the South China Sea. Through this wide breadth of strategic dialogues and maritime exercises and operations, Australia shows its commitment to the maritime domain as well as the international order. So far, the realignment of power in the Asia- Pacific has been without direct conflict.

When it comes to the Pacific, the reality is Australia has placed international order at the forefront of its national security. As the Pacific’s maritime domain continues to evolve and the strategic stability of the post WWII-era is challenged, Australia’s policies toward the region will undoubtedly develop to meet this challenge. Considering Australia’s growing importance to the region, any actions Australia takes will undoubtedly have a significant impact on its regional partners. As such, attempts at polarizing Australia’s maritime policy will only worsen the divide.

As more and more nations feel compelled to choose sides, the likelihood of consensus drives down and the possibility of a bifurcated maritime domain rise. So, when it comes to the United States and China, Australia has not taken sides, nor is it in anyone’s best interests to do so. So far, the realignment of power in the Asia-Pacific has been without direct conflict and Australia plays an integral role in keeping it as such.

Lieutenant David Andre is a former Intelligence Specialist, and has served as an Intelligence Officer and Liaison Officer assigned to AFRICOM. He is currently serving as N2 for COMDESRON SEVEN in Singapore. He can be reached at dma.usn@gmail.com.

Featured Image: Prime Minister of Australia Malcolm Turnbull takes a selfie. (U.S. Embassy Canberra)