By Paul Pryce

In recent years, several detailed analyses have been produced on Iranian efforts to develop the doctrine and capabilities necessary to wage ‘asymmetric naval warfare.’ This has involved preparing the Islamic Republic of Iran Navy (IRIN) and Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Navy (IRGCN) to wage a kind of insurgency in the Strait of Hormuz and the Persian Gulf, employing ‘swarming’ tactics with well-armed small boats and fast-attack craft along with naval mines, submarines, and anything else that might allow Iran to exploit the vulnerabilities of a technologically superior enemy like the United States Navy (USN). In 2008, the Washington Institute for Near East Policy released an excellent example of this analysis less than a year after IRGCN forces captured 15 British Royal Navy personnel that had been operating in Iraqi waters.

Yet there are few detailed analyses of whether the Korean People’s Navy (KPN) – the maritime force of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) – could similarly employ asymmetric warfare to counter the technological superiority of the Republic of Korea (ROK) and its US allies. This is particularly surprising when one considers how Iran has only recently begun to develop such asymmetric capabilities since its mining of the Persian Gulf during the Iran-Iraq War, which saw significant damage to the guided missile frigate USS Samuel B. Roberts in April 1988. The DPRK, meanwhile, has been contending with a capability gap against its southern adversary for far longer. Although IRIN must divide its attention somewhat between the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea, the KPN is truly split into two distinct fleets, one concerned with the Yellow Sea to the west and the other concerned with the Sea of Japan to the east. Simple geography prevents the KPN from ever truly consolidating its forces. This extends, of course, even to shipbuilding, with many vessels in the Eastern Fleet originating at Wonsan Shipyard and much of the vessels in the Western Fleet originating at Nampo Shipyard.

Helped along by the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the decline in availability of Russian military equipment, it seems the DPRK has set about developing its own defence industry and is producing new vessels that, while clearly unable to square off against ROK counterparts, could prove effective at waging asymmetric warfare at sea. Well-suited to swarming, the Nongo-class fast attack craft, which appears to be 35 metres long and displace 200 tons, could harass ROK and USN vessels. Rare glimpses of this vessel in DPRK propaganda footage suggest that the Nongo-class is equipped with a turret-mounted 76mm gun, possibly reverse-engineered from the Italian-designed OTO Melara 76mm, along with a complement of Russian-produced Zvezda Kh-35U subsonic anti-ship missiles.

The prominence of submarines in KPN modernization efforts is also telling. The old Romeo- and Whiskey-class diesel-electric submarines received from the Soviet Union are being phased out in favour of some domestically produced designs. Satellite imagery as recent as July 2014 indicates North Korea is building a submarine with a length of 65.5 metres and a displacement of between 1,000 and 1,500 tons, which has been dubbed the Sinpo-class, for addition to its East Fleet. South Korean media sources, such as Yonhap News, claim that the design is reverse-engineered from a Soviet Golf-II diesel-electric submarine and could deploy ballistic missiles. Others, like the US-Korea Institute at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies, believe the design to be based on older Yugoslavian designs like the Heroj- and Sava-classes. However, little else can be discerned about the lone vessel of this class spotted in satellite imagery.

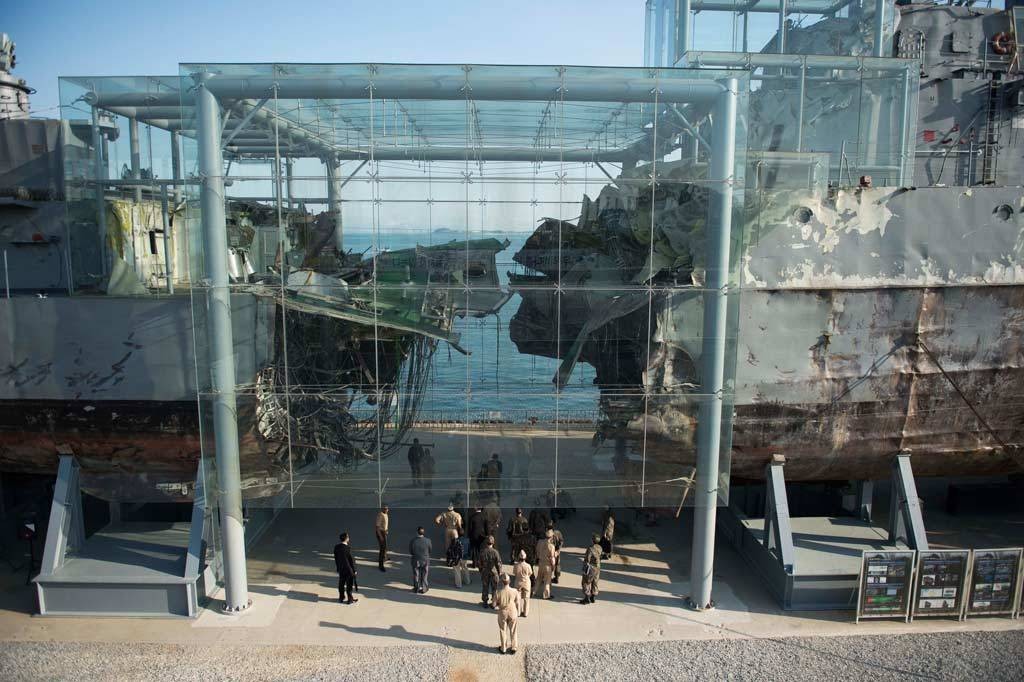

The most compelling aspect of KPN asymmetric warfare to date is the continued prevalence of the Yeono-class midget submarines. First introduced in 1965, these vessels require a crew of only two to operate but can carry six or seven passengers, proving useful for DPRK covert operations against South Korea and Japan. With a submerged displacement of 130 tons and a length of approximately 20 metres, each is armed with two 533mm torpedo tubes. It is believed that a Yeono-class submarine fired the torpedo that sank ROKS Cheonan, one of South Korea’s Pohang-class corvettes, in March 2010. Although the KPN reportedly has only ten Yeono-class submarines left in operation, the attack on ROKS Cheonan demonstrates how such a weapon, deemed obsolete by Western standards, might still present a very real threat to network-centric navies like that of the ROK.

The North Koreans are not alone in recognizing the potency of midget submarines like the Yeono-class. Since 2007, Iran has acquired 14 submarines of this class and is domestically producing its own derivative of the design, known as the Ghadir-class. The convergence of Iranian and North Korean naval doctrine underscores the need for further analysis of the latter’s intentions, capabilities, and potential impact on the security of the Korean Peninsula’s littorals. The KPN’s Soviet submarines and swarms of small Kusong-class torpedo boats might have once seemed to American and South Korean defence planners to be sufficiently straightforward a threat to counter. But the vessels described here demonstrate that the DPRK is adapting to its strategically disadvantaged position and lack of technological sophistication.

This is particularly problematic for the ROK Navy, which has focused so heavily in recent years to attain blue-water status. According to the analysis of Vice Admiral (retired) Yoji Koda of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force, the ROK has limited anti-submarine warfare capabilities. In this sense, the Yeono-class perfectly exploits one of the ROK Navy’s most glaring capability deficits. Satellite imagery may have picked out a vessel as substantial as the Sinpo-class, but what might it miss? Based on the successful engagement against ROKS Cheonan, it would not be a surprise if the DPRK were actively working on a new design based on the Yeono-class. Such small vessels would not be spotted as readily as a 1,500 ton submarine openly berthed at Sinpo South Shipyard.

Another area of some uncertainty regarding DPRK asymmetric capabilities is minelaying. Naval mines were of significant importance to the KPN during the Korean War – so much so that 70% of the casualties suffered by USN vessels during that conflict were due to mines laid by DPRK forces. Yet subsequent research suggests those mines were laid with significant Soviet guidance and training, and it would be a stretch to assume DPRK mine warfare has gained much in sophistication since then. There are also no indications whether the KPN currently operates dedicated minelaying vessels. In the absence of such, DPRK mine warfare would certainly be inefficient but it could, in the most desperate of circumstances, even employ civilian vessels in such a role. For example, during the Korean War blockade of Wonsan, the DPRK made use of local sampans as minelayers. It would be wise of the ROK Navy to not bet on that scenario and invest in improved mine countermeasures.

The DPRK is among the most secretive regimes and so detailed information on its military capabilities is scarce as has been indicated here. Yet what little can be prised from open source information shows that the DPRK is at least as advanced as Iran in its ability for asymmetric warfare at sea. It is vital that further attention be paid to the evolution of the KPN so that, first and foremost, incidents like the sinking of ROKS Cheonan are not repeated, but also to ensure that any potential intervention by the international community against the DPRK proceeds without significant loss of life or assets for the ROK and its allies.

Paul Pryce is Political Advisor to the Consul General of Japan in Calgary and a long-time member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC). He has previously written as the Senior Research Fellow for the Atlantic Council of Canada’s Maritime Nation Program.