The Future of Undersea Competition Topic Week

By Michael Glynn

The last decade has featured rapid advances in computing power, autonomous systems, data storage, and analytics. These tools are double-edged weapons, offering possible advantages to the U.S. while also opening the door to increased adversary capabilities. When combined with legacy systems and current doctrine, these technologies offer the U.S. Navy the chance to retain an advantage in the undersea contests of the future. The service must capitalize on these technologies. If they do not, they should realize that the low barrier of entry may drive potential opponents to do just that, eroding comparative advantage.

For the last 25 years, the Navy’s anti-submarine warfare (ASW) community has enjoyed the luxury of a permissive threat environment. What limited money was available to be spent on ASW was allocated to defensive measures to protect high value units in a close-in fight. The sensors and weapons that make up the stockpile are holdovers or incremental improvements of systems conceived in the late 1980s. The once dominant ASW task forces that tracked fleets of Soviet submarines have suffered from neglect, brain drain, and disuse in the last quarter century.

Despite these challenges, the U.S. currently retains a decisive advantage in the undersea domain. The service’s doctrine has been recently rewritten, and draws lessons from effective ASW campaigns of the past. Full-Spectrum ASW seeks to degrade the submarine threat as a whole.[i] It seeks to attack the adversary kill chain at every point, making damaging and sinking submarines only one piece of the ASW campaign.

Some observers have claimed that advancements in sensor systems and data analysis will strip stealth away from submarines.[ii][iii] This erosion of stealth will not happen unless the U.S. Navy solves three distinct challenges: gathering, analyzing, and disseminating environmental information, integrating operations analysis at the operational and tactical levels of war to maximize sensor and weapons effectiveness, and ensuring that ASW task forces are equipped with standardized equipment and highly effective training. Let’s discuss each of these challenges in detail.

Environmental Information

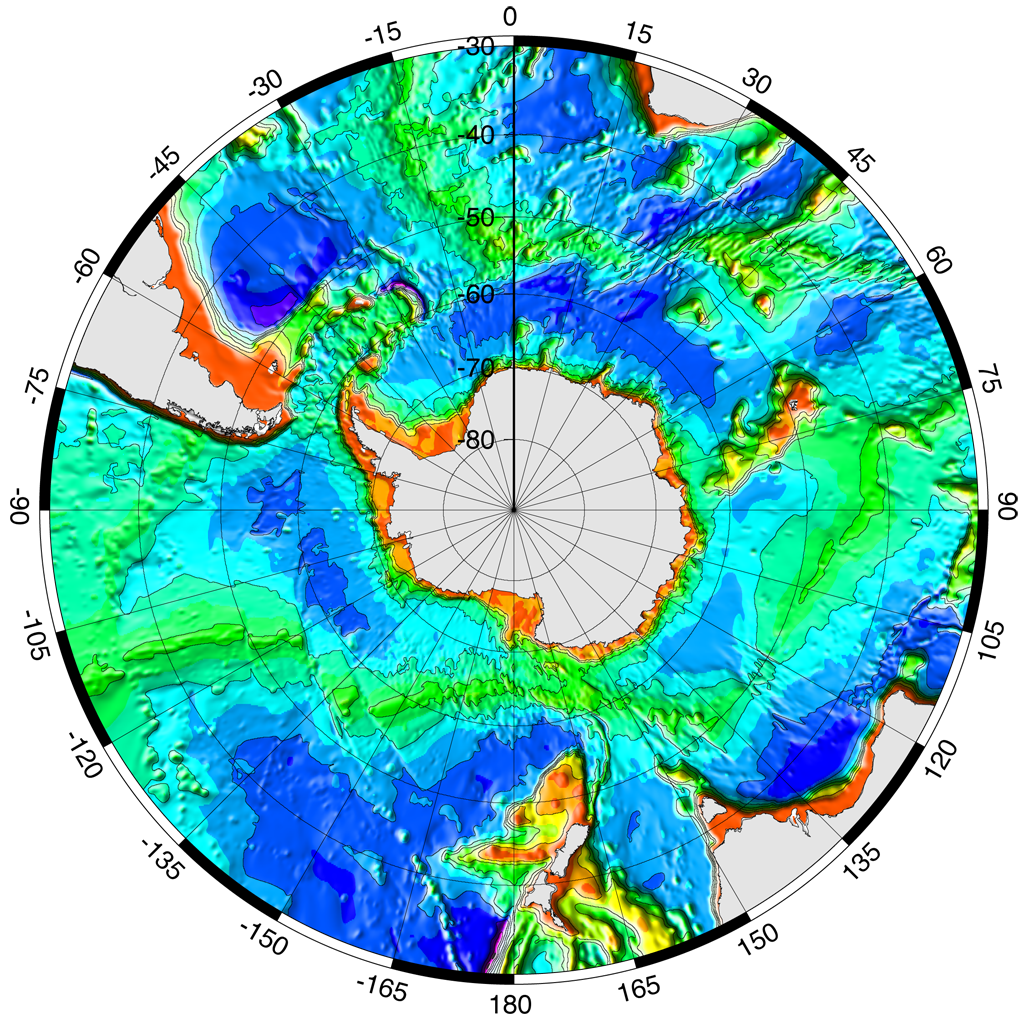

The ocean is an enormously complex and variable warfare domain. The properties of the ocean can change rapidly over small distances, just like weather ashore. Temperature, salinity, pressure variations, and the features of the ocean floor alter the way that sound energy moves through water. Characterizing the environment is critical to conducting effective ASW.

For decades, the Naval Meteorology and Oceanography Command (NMOC) has provided the service with oceanographic and bathymetric information. NMOC

maintains a fleet of survey vessels, gliders, and sensors to gather information on the water-column.[iv] Computers ingest the information and build forecast ocean models.[v][vi]Operational planners and ASW operators use these products to model how sound energy will travel between their sensors and the submarine they are hunting. Without accurate ocean models, ASW operations are exercises in guesswork. Models are critical tools for effective ASW.

The Navy of tomorrow will need to make better use of the environmental data it collects and the models it produces. Many tactical platforms constantly collect data such as ambient noise or sound velocity profiles. Unfortunately, much of this raw data never makes it back to NMOC, due to communications limitations and process shortfalls. This hurts the quality of oceanographic models, and means the fleet will show up to the fight already at a disadvantage.

The undersea competition of the future will feature better dissemination and use of oceanographic models and bathymetric information. Ships and aircraft will automatically record environmental data and upload it to NMOC databases. When bandwidth makes it possible, ships, submarines, and aircraft should be constantly fed the most recent environmental model and use this information to drive radar and sonar performance predictions inside their combat systems. Fusion algorithms will automatically ingest real-time environmental measurements from sensors in the water to merge with the model and improve the accuracy of sonar performance predictions.

Operations Analysis

In the past, ASW planners have been able to degrade their adversary’s submarine force and maximize the effectiveness of a small number of ASW platforms by using operations analysis. In World War II, the British Submarine Tracking Room and U.S. ASW Operations Research Group used all-source intelligence to re-route convoys, assign aircraft to guard threatened ships, target submarine transit routes, and hunt down individual high-value submarines.

During the Cold War, the U.S. Navy used applied mathematics and computational modeling to predict the location of Soviet submarines. These search systems used track information of past patrols to build models of how Soviet commanders tended to operate. Cueing information was used to identify high probability search areas and recommended platform search plans.[vii] Real-time updates of positive and negative information during a search were fed to the computer to modify the search as it progressed.[viii] These computerized systems allowed planners to double their rate of successful searches compared to manual planning methods.[ix] Despite two decades of operational success, these planning systems were defunded and shut down after the collapse of the Soviet Union.

ASW forces of tomorrow will have to rediscover the value of operations analysis and apply these efforts at the operational and tactical levels. ASW task forces will be equipped with all-source intelligence fusion centers. Cueing information will flow from traditional means such as the Integrated Undersea Surveillance System, signals intelligence, and novel means assisted by big data analytics. Methods as unusual as monitoring the social media or Internet activity of adversary crew members and their families may provide indications that a submarine is getting underway.

Legacy computational search systems could only be run ashore due to the limits of processors of the day. Today’s hardware allows these systems to be run on a laptop. In the near future, tactical platforms will ingest cueing information and generate employment plans for themselves and assets nearby. A P-8A will generate optimized sonobuoy drop points, sonar dip points for two MH-60R’s flying nearby, and search plans for an ASW Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle and three unmanned underwater vehicles.[x][xi] The search plans and sensor points will automatically be broadcast via Link 16 and other future networks. The ability to direct multiple ASW platforms in today’s environment exceeds human capabilities, but tactical operations analysis systems will reverse this deficiency.

Optimized Task Force Training and Equipment

The final key to enabling next generation information management is revamping the equipment and training of the task forces who direct ASW at the Combatant Commander level. The increasing lethality of cruise missile armed submarines means focusing ASW planning at the Carrier Strike Group (CSG) level and fighting a close-in defensive battle is unacceptably risky. Future ASW campaigns will be won or lost at the theater level, with CSGs being only one piece of a multi-faceted approach. While 25 years of low budgets and disuse have blunted theater ASW (TASW) task forces, it is these commands that will direct the undersea battles of tomorrow.

Today, each TASW task force uses a hodgepodge of various systems and local information management procedures that have grown up to fit the unique challenges of the area. Lack of oversight means each task force uses its own training syllabus, communications procedures, and unique methods to maintain a common operating picture (COP). Despite this disunity, personnel are expected to flow from one task force to another in times of crisis and seamlessly master a system they have never trained with. This is not a recipe for success in an increasingly complicated information management environment.

The Navy should ensure each TASW task force is equipped with a standard suite of analysis and information management tools. The forces will adopt and master the Undersea Warfare Decision Support System and maintain a worldwide COP backed up at each task force. Standardized qualifications cards, methods for maintaining the COP, and disseminating information will allow personnel to rapidly surge and integrate with another task force. An open architecture construct will allow adjustments in managing relationships with regional allies, information release, and the unique nature of the adversary threat.

The aviation community uses the Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center to develop and rigorously standardize tactics. The surface community has recognized that standardized employment and highly trained Weapons and Tactics Instructors are crucial for operating today’s exquisitely complex and capable weapon and sensor systems.[xii] The TASW community should adopt a similar focus on standardization of information management and search employment, just as their colleagues in the aviation and surface communities have. The Undersea Warfighting Development Center will take a much more central role in tactics development and employment standardization.

Conclusion

Operations analysis has proven itself a force multiplier in ASW. This will be critical as fleet size continues to shrink. In the information age, the problem is not too little ASW information, but rather how to properly ingest, analyze, and disseminate information. If the Navy capitalizes on the opportunities listed above, it will be well on its way to maintaining undersea superiority. If it does not, it should remain wary that the barrier for entry for other nations to build effective information management and operations analysis systems is low. The technology required is relatively cheap and has current commercial applications. There is extensive open source literature on the topic. Without having to contend with an entrenched defense bureaucracy and legacy programs of record that stifle innovation, these nations will certainly seek to rapidly capitalize on these concepts as a means to disrupt U.S. undersea superiority.

Lieutenant Glynn is an active-duty naval aviator. He most recently served as a member of the CNO’s Rapid Innovation Cell. The views expressed in this piece are entirely his own and do not represent the position of the Department of the Navy.

[i] William J. Toti, “The Hunt for Full-Spectrum ASW,” Proceedings, (June 2014), http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-06/hunt-full-spectrum-asw, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[ii] Bryan Clark, “The Emerging Era in Undersea Warfare,” (Washington, D.C.: Center for Strategic and Budgetary Analysis, January 22, 2015), http://csbaonline.org/publications/2015/01/undersea-warfare/, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[iii] James Holmes, “U.S. Navy’s Worst Nightmare: Submarines may no Longer be Stealthy,” The National Interest, (June 13, 2015), http://nationalinterest.org/feature/us-navys-worst-nightmare-submarines-may-no-longer-be-13103, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[iv] “Oceanographic Survey Ships – T-AGS,” (U.S. Navy, August 23, 2007), http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=4500&tid=700&ct=4, (accessed May 23, 2016).

[v] “Naval Oceanographic Office Global Navy Coastal Ocean Model (NCOM),” (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration), https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/model-data/model-datasets/navoceano-ncom-glb, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[vi] “Naval Oceanographic Office Global Hybrid Coordinate Ocean Model (HYCOM),” (National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration), https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/data-access/model-data/model-datasets/navoceano-hycom-glb, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[vii] Henry R Richardson, Lawrence D. Stone, W. Reynolds Monach, & Joseph Discenza, “Early Maritime Applications of Particle Filtering,” Proceedings of SPIE, Vol. 5204, 172-173.

[viii] Daniel H. Wagner, “Naval Tactical Decision Aids,” (Monterey: Naval Postgraduate School, September 1989), II-5.

[ix] J. R. Frost & L. D. Stone, “Review of Search Theory: Advances and Applications to Search and Rescue Decision Support,” (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Coast Guard, 2001), 3-4.

[x] “Anti-submarine Warfare (ASW) Continuous Trail Unmanned Vehicle (ACTUV),” (Arlington, VA: Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency), http://www.darpa.mil/program/anti-submarine-warfare-continuous-trail-unmanned-vessel, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[xi] Michael Fabey, “ONR Seeks Long-Duration, Large-Diameter UUV’s,” Aviation Week, (October 29, 2012), http://aviationweek.com/defense/onr-seeks-long-duration-large-diameter-uuvs, (accessed May 22, 2016).

[xii] Sam LaGrone, “Navy Stands up Development Center to Breed Elite Surface Warfare Officers,” USNI News, (June 9, 2015), https://news.usni.org/2015/06/09/navy-stands-up-development-command-to-breed-elite-surface-warfare-officers, (Accessed May 22, 2016).

Featured Image: A P-8A Poseidon surveillance plane conducts flyovers above the Enterprise Carrier Strike Group on February 3, 2012. REUTERS/U.S. Navy/Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Daniel J. Meshel/Handout