By Pawel Behrendt

Two years ago, President Xi Jinping announced the reorganization of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and the implementation is gaining momentum. The changes, which go far beyond administrative restructuring and equipment modernization, will make the world’s most massive fighting force more modern and flexible. The reorganization gives Xi and his team an opportunity to purge political opponents within the military and address many of the problems that have plagued the military for decades.

During his speech to the National People Congress in 2012, Hu Jintao announced the modernization of the PLA, seeking a modern armed force, able to “win local wars under informationized/hi-tech conditions.” Under Xi Jinping, these modernizations began to materialize. The first noticeable change was the restoration of political officers in the PLA, a clear sign of turbulent relations between the new leadership and the generals. Next, Xi announced a wide-reaching anti-corruption campaign. Most notably, former deputy chairmen of the Central Military Commission, Generals Xu Caihou, and Guo Boxiong, were among those accused of corruption. Their fate was settled in 2016 – Xu died of cancer while under arrest and Guo was sentenced to life in prison.

With the backdrop of the anti-corruption campaign, a real military reform was afoot – in 2014, a reorganization of the command structure was announced. The number of military regions was reduced from 7 to 5, and a joint operation command was established to coordinate actions of ground, air, and naval forces in each area. There was also an increase in the role of the Air Force and Navy, both of which are more prominent in a state with global ambitions as opposed to an Army-dominated system that has long characterized China’s military. In celebration of the 70th anniversary of World War II, Xi Jinping announced the reduction of the PLA by 300,000 soldiers to 2 million standing troops. On the last day of 2015, amid overall personnel reduction, new military branches were established – the Rocket Force and the Strategic Support Force.

2016 brought about important, but less flashy, changes. Specifically, the creation of a DARPA-equivalent research lab was announced in March 2016. The agency was operational in July 2017. In April 2016, military education reform was announced and, as a result, departments related to land forces reduced the number of freshmen by 24 percent and the departments of logistics and support shrunk by 45 percent. Conversely, the number of students admitted to courses related to aviation, Navy, and missile technologies was increased by 14 percent. An increase of 16 percent was planned for departments related to space technologies, radars, and drones.

Further, closer cooperation between universities and training units was also announced. This was the result of increasingly louder complaints that soldiers cannot take full advantage of the increasingly modern equipment. Overcoming this gap is now considered one of the most critical tasks to the PLA. Xi Jinping stressed several times a great need for officers who have a broad knowledge of advanced technologies. Most concerning is the shortage of IT specialists. Like many other countries, Chinese IT companies offer much better compensation and work conditions, robbing the military of talent. Higher military income and attractive career paths are being implemented to prevent the talent bleed. Further, to attract talented college graduates, the draft was aligned with the college graduation season.

In September 2016, the activation of the Joint Logistics Support Force was announced. This step aims to improve the decentralized PLA logistics system. Within each of the military regions, a Regional Joint Logistics Support Center was established with headquarters in Wuxi, Guilin, Xining, Shenyang, and Zhengzhou. Of note, the Joint Logistics Support Force is not subordinate to the PLA HQ, but to the Central Military Commission.

Starting in 2017, even more radical changes were made. In mid-March, a five-fold increase in the size of the Marine Corps was announced. The force now numbers 20,000 soldiers organized in two brigades, but the goal is as many as 100,000 troops in six brigades. The greatly expanded Marine Corps is dedicated primarily to the protection of the maritime thread of the One Belt, One Road, and defense of the overseas interests of the Middle Kingdom. The Chinese Marines will be permanently stationed in Gwadar, Pakistan, and in Djibouti. The African garrison is rumored to have as many as 10,000 soldiers. It is important to mention that, according to media sources, the first Type 075 amphibious assault ship was laid down in March 2017. Specifics on the ship design and numbers are still unknown. The Chinese Admiralty wanted LHDs similar to the American WASP-class but opted for a smaller ship – based on the French Mistral-class – due to financial constraints. Recent information suggests that “something in between” has been chosen.

Amphibious assault ships are necessary if China wants “American style” power-projection capability. The Chinese are well aware of the unique requirements of the Marines, and outdated PLAN Marine Corps equipment is discussed openly. The force has spent years preparing for an invasion of Taiwan and operations in the nearby waters of South and East China Seas requires a thorough reorganization.

The marine brigades of the PLAN are not the only amphibious assault units of the PLA. There are also four amphibious mechanized infantry divisions (AMID) that are part of the PLA Ground Force. These units are essentially mechanized divisions equipped with more amphibious vehicles and river crossing equipment. In effect, the divisions are more suited to crossing rivers and lakes than in taking part in actual seaborne operations. Under the reorganization of the PLAN Marines Corps, the future of AMID is unclear.

Around the same time that the PLAN Marine Corps reports emerged, PLA Ground Force restricting was also announced. From 1949 through the mid-1980s, the Ground Force was organized into 70 corps. Then, during one of the previous reorganizations, the number was halved and later reduced to 24. At the same time, the corps were renamed “group armies.” During subsequent reductions in the 1990s and 2009, their number fell to 21 and, eventually, to 18 corps. Now, the group armies are returning to corps and further decreased in number to 13. This change, however, has a deeper meaning. Specifically, the 16th and 47th Group Armies will be disbanded. Both are large units and were closely linked to the aforementioned Generals Xu and Guo. According to social media, not all soldiers from disestablished units will leave the military – some may be reassigned, even to the Air Force, Navy or Rocket Force. Some of the other units that will be disbanded are the 14th, 20th, 27th and 40th group armies.

In April 2017, further information was officially disclosed by the Ministry of Defense, when it revealed an even more drastic reorganization. The entire PLA will be divided into 84 corps that will comprise all military branches, as well as garrisons, reserves, military academies, and research units. This means an interruption of historical continuity, cultivated mainly in the Ground Force, in which new army corps will have numbered from 71 to 83. Most of them will be located in northern and western China, opposite the U.S. forces and Japan, but also Russia and North Korea.

Airborne units have also undergone serious organizational changes. Until 2017, there had been three airborne divisions (43rd, 44th, and 45th), organized into the 15th Airborne Corps, subordinate to the PLAAF. Each division consisted of two airborne regiments, a special forces group, an air transport regiment, and a helicopter group. After the recent reorganization, the PLA Airborne Corps was created, and separate divisions were disbanded. Airborne regiments were reclassified as brigades (127th, 128th, 130th, 131st, 133rd, and 134th), and special forces and transport groups were organized into separate brigades. Confusingly, signal, chemical and engineering troops have been assigned into a single brigade. This solution is perceived as the next step in the development of a robust Chinese airborne force and their transformation from light troops into heavily armed units modeled after Russian paratroops.

The large-scale reorganization of the armed forces has also brought about some unexpected personnel problems. Public protests by active duty servicemen and veterans have become common, and the primary cause of dissatisfaction is not only the reduction of posts. Unlike previous cuts, the severance pay program and employment efforts for former military personnel failed. In fact, pay and military pensions sometimes arrived late or in reduced sum. Veterans are particularly embittered, and they accuse the government of ignoring their needs and problems. In October 2017, more than 1,000 vets protested at the Ministry of Defense singing military songs and waving party flags. Police and security officers were confused and surrounded the protesters with buses and police vehicles. On October 11, another protest lasted late into the night, resulting in several arrests. According to human rights organizations, protests are not rare, with over 50 occurring in 2016 alone. As a result, a special Ministry of Veterans Affairs was established in March 2018. The new institution will help veterans to find jobs, lodging, and ensuring their status of “revered members of society.”

Conclusion

A reorganization of a structure as big and complex as the PLA is never an easy task and it is compounded by resistance from active and veteran military personnel. Unlike the USSR, there is no clear division between party, military, and security force. Further, the military has always had a strong influence on the state apparatus. During his second term, Hu Jintao warned about the negative consequences of this system. Despite silencing the most hostile officers whose status and influence were endangered by the reform, protests by lower ranks and veterans show that the Communist Party of China has to be very careful. From the military point of view, the reform aims to convert the force designed primarily to defend Chinese territory into one prepared for expeditionary operations.

Pawel Behrendt is a Political Science Ph.D. candidate at the University of Vienna. He is an expert at the Poland-Asia Research Center and is the deputy chief-editor of konflikty.pl. Find him on Twitter @pawel_behrendt.

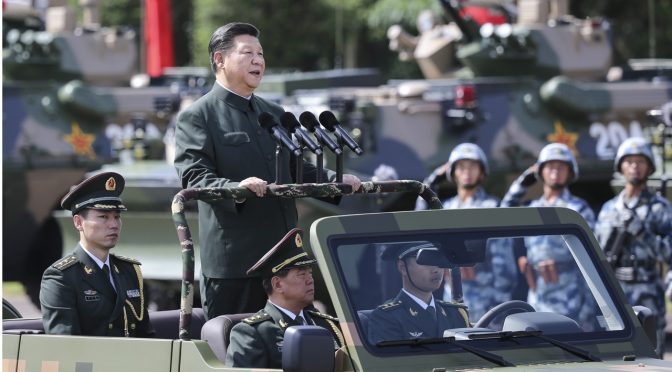

Featured Image: Chinese marines (Xinhua)