Ever wonder what is happening in the Arctic? Sea Control: North America host Matthew Merighi interviews three graduate students running the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy’s annual Arctic Conference: Molly Douglass, Rabia Altaf, and Drew Yerkes. The interview examines border claims, resource politics, and how the various regional actors are approaching this new frontier.

Ever wonder what is happening in the Arctic? Sea Control: North America host Matthew Merighi interviews three graduate students running the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy’s annual Arctic Conference: Molly Douglass, Rabia Altaf, and Drew Yerkes. The interview examines border claims, resource politics, and how the various regional actors are approaching this new frontier.

Tag Archives: Arctic

Breaking the Ice: The US Chairmanship in the Arctic Council

By Paul Pryce

Sometimes the best resources are not hidden behind a paywall but are freely made available to researchers. Thanks to the Congressional Research Service’s 114-page report Changes in the Arctic: Background and Issues for Congress by Ronald O’Rourke, with a recent version released in September 2015, such is the case for those wishing to understand strategic trends in the Arctic from the perspective of the United States. This is especially timely, as US President Barack Obama toured Alaska from August 31, 2015, becoming the first American president to visit America’s Arctic region. On September 4, just days after President Obama arrived in Alaska and the very same day the CRS released its report, five People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) vessels – three surface combatants, an amphibious landing vessel, and a replenishment ship – entered within twelve miles of the Alaskan coastline.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

The report offers a comprehensive overview of legislation and international agreements concerning the Arctic, as well as the economic opportunities yet to be realized in the Chukchi Sea, Beaufort Sea, and elsewhere in the region. Although Shell has since cancelled its plans for offshore drilling in the Chukchi Sea, oil and other commodity prices could at some point in the future return to levels where Arctic resource exploitation becomes profitable once again. Arctic shipping is also becoming viable – that much was made clear when MV Yong Sheng became the first container-transporting vessel to transit from its home port in China along the Northern Sea Route, Russia’s Arctic waterways, to reach Rotterdam, Netherlands in August 2013. It is this increased opportunity for business in the region which presents new challenges for the United States Coast Guard (USCG) and United States Navy (USN).

As the report highlights, eight ships were lost in Arctic Circle waters in 2006. Less than a decade later, in 2014, there were 55 ship casualties in these waters. Thus far, the risk to human life and environmental impact of these accidents have been relatively limited, but it is apparent that US maritime forces currently lack the means to respond quickly and effectively to a serious disaster in the country’s Arctic waterways. The CRS highlights two capability gaps: basing and icebreaking.

Currently, the largest USCG base is located at Kodiak Island, which is on the south coast of Alaska near the Aleutian Range. USCG vessels operating from Base Support Unit Kodiak could respond quickly to an incident along existing shipping lanes near the Bering Sea but would need days or even weeks to reach the site of a ship collision or oil spill in the Chukchi Sea or Beaufort Sea. The US Army Corps of Engineers has been investigating the suitability of other Alaskan communities, specifically Nome or Port Clarence, as possible sites for a deepwater port from which USCG vessels could operate in the future. Located much further north along the Alaskan coast – jutting out into the Bering Strait in fact – either location would significantly cut down USCG response times in the Chukchi Sea. Port Clarence is already home to a small USCG presence: a 4,500 foot long paved runway capable of accommodating search-and-rescue (SAR) aircraft. Until a deepwater port is established within range of the Chukchi Sea, however, the US capacity to exert sovereignty in the Arctic will be severely limited.

The other capability gap identified in the report relates to the USCG’s shrinking fleet of icebreakers. After USCGC Polar Sea suffered an engine casualty in June 2010, the US has only the heavy polar icebreaker USCGC Polar Star and the medium polar icebreaker USCGC Healy at its disposal. Although Polar Star was refurbished and re-entered service in December 2012, this is only expected to extend the vessel’s service life until approximately December 2022. Unless Polar Sea is repaired or the White House significantly steps up efforts to acquire a new heavy polar icebreaker, the USCG could soon find itself unable to reach the US’ northernmost waterways due to sea ice cover. Much as the USCG is currently under-equipped to project American power in the Arctic, the USN also suffers a capability gap. The updated Navy Arctic Roadmap for 2014-2030, which was release in February 2014, acknowledges that opportunities for Arctic transits will be limited in the near term but commits to obtaining the capability necessary to operate for sustained periods in the Arctic by the 2020’s.

How the USN intends to attain this capability in the mid-term is unclear. In 2002, the Norwegian Coast Guard gained the icebreaking-capable offshore patrol vessel Svalbard, which has ensured a permanent presence for Norway in the Barents Sea and the Arctic waterways surrounding the Svalbard Islands. By spring 2018, the Royal Canadian Navy will begin taking delivery for the first of its new Harry DeWolf-class Arctic offshore patrol ships, a fleet of five to six vessels with some limited icebreaking capabilities and a similarly sustained presence in Canada’s expansive Arctic territory. The USN will presumably need vessels with characteristics closely resembling those of the Harry DeWolf-class and Svalbard-class; ice strengthening ships from the Military Sealift Command (MSC) as proposed in the Arctic Roadmap would very likely be insufficient, especially when China has demonstrated a willingness to engage in freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) in American-claimed waters and the Russian Federation is aggressively expanding its already impressive icebreaking capabilities.

The Arctic Coast Guard Forum (ACGF), which was established in October 2015, will ensure some level of security for Arctic shipping and may even go toward reducing tensions in the region. Canada, which chaired the Arctic Council from 2013 until April 2015, endeavoured to establish just such a forum for exchange among the coast guards of the Arctic Council’s eight member states (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, Sweden, and the US) but was unable to bring the Russians to the negotiating table. The US, which will chair the Arctic Council until April 2017, is clearly willing to assemble a toolbox of so-called ‘confidence and security-building measures’ (CSBM’s) to ensure any future disputes in the Arctic are resolved peacefully. With the conclusion of an Arctic Search and Rescue Agreement (ASARA) in 2011, which clarifies which states have responsibility for SAR operations in certain Arctic waterways, there is clearly a growing interest in cooperatively policing Arctic waterways.

As outlined here, the CRS report is a valuable resource for those wishing to gain a strong basis of understanding with regards to the Arctic. Readers are fortunate, then, that an updated edition of the report continues to be released almost quarterly.

Paul Pryce is a Senior Research Fellow at the Atlantic Council of Canada and a Board Member at the Far North Association. He is also a long-time member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC).

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

Yours, Mine, and Moscow’s: Breaking Down Russia’s Latest Arctic Claims

This article originally featured on CIMSEC on August 25, 2015, and has been updated for inclusion into the Russia Resurgent Topic Week.

By Sally DeBoer

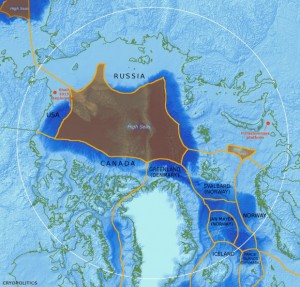

On August 4th, the Russian Federation’s Foreign Ministry reported that it had resubmitted its claim to a vast swath (more than 1.2 million square kilometers, including the North Pole) of the rapidly changing and potentially lucrative Arctic to the United Nations. In 2002, Russia put forth a similar claim, but it was rejected based on lack of sufficient support. This latest petition, however, is supported by “ample scientific data collected in years of arctic research,” according to Moscow. Russia’s latest submission for the United Nation’s Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf’s (CLCS) consideration coincides with increased Russian activity in the High North, both of a military and economic nature. Recent years have seen Russia re-open a Soviet-era military base in the remote Novosibirsk Islands (2013), with intentions to restore a collocated airfield as well as emergency services and scientific facilities. According to a 2015 statement by Russian Deputy PM Dmitry Rogozin, the curiously named Academic Lomonsov, a floating nuclear power plant

built to provide sustained operating power to Arctic drilling platforms and refineries, will be operational by 2016. Though surely the most prolific in terms of drilling and military activity, Russia is far from the only Arctic actor staking their claim beyond traditional EEZs in the High North. Given the increased activity, overlapping claims, and dynamic nature of Arctic environment as a whole, Russia’s latest claim has tremendous implications, whether or not the United Nations CLCS provides a recommendation in favor of Moscow’s assertions.

The Claim:

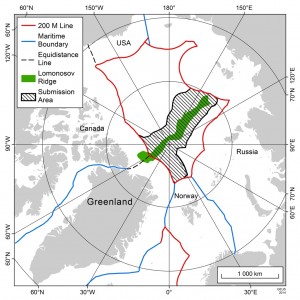

Russia’s August 2015 claim encompasses an area of more than 463,000 square miles of Arctic sea shelf extending more than 350 nautical miles from the shore. If recognized, the claim would afford Russia control over and exclusive rights to the economic resources of part of the Arctic Ocean’s so-called “Donut Hole.” As the New

York Times’ Andrew Kramer explains, “the Donut Hole is a Texas sized area of international waters encircled by the existing economic-zone boundaries of shoreline countries.” As such, the donut hole is presently considered part of the global commons. Moscow’s claim is also inclusive of the North Pole and the potentially lucrative Northern Sea Route (or Northeast Passage), which provides an increasingly viable shipping artery between Europe and East Asia. With an estimated thirteen percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and thirty percent of its undiscovered natural gas, the Arctic’s value to Russia goes well beyond strategic advantage and shipping lanes. Recognition by the CLCS of Russia’s claim (or any claim, for that matter) would shift the tone of activity in the Arctic from generally cooperative to increasingly competitive, as well as impinge on the larger idea of a free and indisputable global common.

The Law:

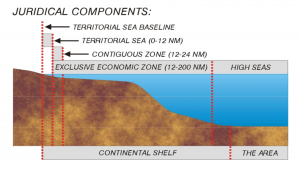

As most readers likely already know, the United Nations’ Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) allows claimants 12nm of territorial seas measured from baselines that normally coincide with low-water coastlines and an exclusive economic zone (EEZ)

extending to 200 nautical miles (inclusive of the territorial sea). Exploitation of the seabed and resources beyond 200nm requires the party to appeal to the International Seabed Authority unless that state can prove that such resources lie within its continental shelf. Marc Sontag and Felix Luth of The Global Journal explain that “under the law, the continental shelf is a maritime area consisting of the seabed and its subsoil attributable to an individual coastal state as a natural prolongation of its land and territory which can, exceptionally, extend a states right to exploitation beyond the 200 nautical miles of its EEZ.” Such exception requires an appeal to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), a panel of experts and scientists that consider claims and supporting data. Essentially, the burden is on Russia to provide sufficient scientific evidence that its continental shelf (and thus its EEZ) extends underneath the Arctic. In any case, as per UNCLOS Article 76(5), such a continental shelf cannot exceed 350 nm from the established baseline. Russia’s latest claim is well beyond this limit; the Federation has stated that the 350 nm limit does not apply to this case because the seabed and its resources are a “natural components of the continent,” no matter their distance from the shore.

The CLCS will present its findings in the form of recommendations, which are not legally binding to the country seeking the appeal. Though Russia has stated it expects a result by the fall, the commission is not scheduled to convene until Feburary or March of 2016 and, as such, there will be a significant waiting period before any recommendation will be made.

Rival Claimants:

Russia is far from the only Arctic actor making claims beyond the 200 nautical mile EEZ. Denmark, for instance, jointly submitted a claim with the government of Greenland expressing ownership over nearly 900,000 square kilometers of the Arctic (including the North Pole) based on the connection between Greenland’s continental shelf and the Lomonosov Ridge, which spans  nearly the entire diameter of the donut hole. This claim clearly overlaps Russia’s latest submission, which is also based on the claim that the ridge represents an extension of Russia’s continental shelf. Though there is no dispute on the ownership of the ridge, both Russia and Denmark claim the North Pole. Both nations have recently expressed a desire to work cooperatively on a resolution, though a Russian Foreign ministry statement did estimate a solution could take up to 10-15 years. Also of note: this has note always been Russia’s tune on the matter (See here and here).

nearly the entire diameter of the donut hole. This claim clearly overlaps Russia’s latest submission, which is also based on the claim that the ridge represents an extension of Russia’s continental shelf. Though there is no dispute on the ownership of the ridge, both Russia and Denmark claim the North Pole. Both nations have recently expressed a desire to work cooperatively on a resolution, though a Russian Foreign ministry statement did estimate a solution could take up to 10-15 years. Also of note: this has note always been Russia’s tune on the matter (See here and here).

Similarly, Canada is expected to make a bid to extend its Arctic territory. Notably, Canada claims sovereignty over the Northwest Passage, a shipping route connecting the Davis Strait and Baffin Bay based on historical precedent and its orientation to baselines drawn around the Arctic Archipelago. The U.S. maintains that the Northwest Passage should be an international strait. Though they have yet to submit a formal claim to the UN’s CLCS, one has reportedly been in preparation since 2013. According to reports, Canada delayed a last-minute claim at the behest of PM Stephen Harper, who insisted the claim include the North Pole. If this holds true, Canada’s claim will likely overlap both Russia and Denmark’s submissions to the CLCS. If the CLCS were to recognize the legitimacy of two or more states’ overlapping claims, the actors have the option to bilaterally or multilaterally resolve the issue to their satisfaction; developing such a resolution is beyond the scope of the commission.

Implications:

Likely, Russia’s submission to the United Nations is part of a larger campaign by Moscow to reassert and re-establish its influence in the international order by virtue of its status Arctic influence. Regardless of approval or rejection by the UN, Russia’s expansive claim highlights Moscow’s very serious intention to control and exploit the Arctic. As the Christian Science Monitor’s Denise Ajiri explains, “a win would mean access to sought after resources, but the petition itself underscores Russia’s broader interest in solidifying its footing on the world stage.” With much of Western Europe reliant on Russian oil and natural gas, the Arctic and its resources represent an opportunity for the Kremlin to boost their position in the international order and develop a source of sustained and significant income. Russia may be acting within the letter of the law on the issue of their claim at this time, but it’s hard to separate that compliance from the Federation’s significant investment in the militarization of the Arctic, frequent patrols along the coastline of Arctic neighbors, and expenditure on the economic exploitation of the High North. For now, the donut hole remains part of the global commons and therefore free from direct exploitation or claim of sovereignty. The burden of proof on any one state to claim an extension of their continental shelf is truly enormous, but as experts and lawyers at the CLCS pore over these claims, receding Arctic ice combined with economic and strategic interests of the claimants will likely increase the claimants’ sense of urgency.

Sally DeBoer is a 2009 graduate of the United States Naval Academy and a recent graduate of Norwich University’s Master of Arts in Diplomacy program. She can be reached at Sally.L.DeBoer@gmail(dot)com or on twitter @SallyDeBoer.

Russia in the Arctic: aggressive or cooperative?

By Laguerre Corentin

Since the early 2000s, Russia has begun to pay more attention to the Arctic when its general socioeconomic situation had improved.1 With the ice melting, other Arctic and non-Arctic countries demonstrated their interest for the region, creating territorial disputes. In the High North, Russia is often seen as taking an aggressive approach to assert its sovereignty and the West have been worried about Russia’s involvement in the region, especially after the Ukrainian Crisis and the Russian position in Syria. However, is Russia aggressive in the Arctic? We argue that Moscow is likely to promote cooperation with the Arctic states, but with its interests and national security in mind. The Arctic is of strategic importance for Russia because of its natural resources. Indeed, since the end of the Soviet era, Moscow does not see the region as a potential theatre of a strategic struggle with the West. Moreover, in its history, Russia took care to avoid escalating incidents, favoured cooperation, and the respect of international law in the Arctic because it was in its interest. Russia has learned that it could use the law and international organisations to its advantages. Putin’s aggressive tone seems more to fulfil domestic purposes rather than represent Russia’s intentions in the Arctic. To support our thesis it is useful to look at the country’s historical reliance upon legislation and treaties in the region, its current interests, and its emphasis on cooperation in the resolution of disputes.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

A history of reliance on legislation

Lincoln E. Flake argues that Russia’s current posture on the Continental Shelf is “a natural extension of Tsarist and Early Soviet policies on Arctic land territory”. Russia’s approach to the arctic issues seems to be impacted by previous policies.2 The first experience in claiming land and maritime control in the greater Arctic region occurred in its North American territories with the 1821 Ukase of Alexander I that had both a land and a maritime component. When the neighbouring states rejected the maritime component of the decree, the sole attempt by the Russian government to enforce it was the seizure of the USS Pearl in 1822, but the vessel was released and the maritime component of the decree was abandoned. Each time the Tsarist government tried to enforce a contested decree; it yielded to pressure and abandoned its maritime claims.3 Later, the Soviet government took advantage of treaties to advance its positions. As an example, the 1920 Svalbard treaty assured the Norwegian recognition of the Soviet government. Inadvertently, this treaty was favourable to the USSR by creating a demilitarised zone at the door of its Arctic sector. This event likely demonstrated to the Kremlin that sovereignty issues could be resolved through international treaties to Russia’s advantage. Each time, the authorities used the law to respond to sovereignty issues. Moscow developed a more detailed legislation about its control over the North Sea Route when it was handicapped from preventing foreign military navigation along its Arctic coastline. Moreover, Russia engaged in efforts to arrive at international treaty-based regimes favourable to its claims. This approach led to international conferences that ultimately resulted in the 1982 UNCLOS agreement, which was a resounding victory for Soviet aims in the Arctic.4

Russia’s renewed interests in the Arctic

Today, Russia considers the Arctic as a region of strategic importance for its national security due to the presence of the two-thirds of the Russian sea-based nuclear bases, and the direct access to the Arctic and Atlantic oceans provided by the Kola Peninsula. However, with the end of the Cold War, the region has lost its former military strategic significance as a zone of potential confrontation with the US/NATO.5 Principally, the Arctic is relevant to Russia’s economy and security because Moscow views a prosperous and secure supply of energy as a means of projecting its power in the world. Thus, the Arctic is directly linked to its economic interests. Around 20 percent of its gross domestic product is generated north of the Arctic Circle, as are 20 percent of Russia’s total exports in energy.6 On 18 September 2008, then-President Dmitri Medvedev approved the Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic Up to and Beyond 2020. The document defined the Russian interests in the region – developing the resources in the Arctic, turning the NSR into a unified national transport corridor, maintaining the region as a zone of peace and international cooperation and transforming the Arctic as a “leading strategic resource base”.7 In addition, Russia’s National Security Strategy to 2020, released in May 2009, confirms the importance of the energy sector and connects the country’s success with its status as an energy provider, noting that energy-related issues and regions like the Arctic, the Caspian Sea and Siberia are an important component of its security planning.8

An emphasis on cooperation

In line with the approach developed in the early 2000, the 2013 Concept directs foreign policy to “strengthen Russia’s trade and economic position within the system of world economic relations”, and to use the “capabilities of international and regional economic and financial organisations” to support its economic interests. The Concept shows Russian willingness to work with institutions – particularly the UN – and to be more active internationally. A stated objective of its foreign policy has therefore been to emphasise institutions and issues that elevate its power status. If Putin was critical of Western initiatives and opposed them while employing a more aggressive tone, Russia has committed to more multilateral governance in the Arctic than other countries. Moreover, the Foundations of the State Policy of the Russian Federation in the Arctic for the Period Up to and Beyond 2020 identifies the Arctic as a zone of cooperation. The document asserts Russia’s willingness to work bilaterally and within the framework of regional organisations. Moscow has also taken care not to allow minor skirmishes to escalate.9 These elements balance the plans to extend the Northern fleet’s operational radius and the reinforcement of combat readiness on the Arctic coast. Furthermore, different Russian documents reveal that military security is not a priority, the emphasis being placed on economic concerns. This approach suggests that Russian threat perception is less concerned with strategic confrontation than with challenges to navigational assertions. In this regard, Russian military developments in the Region can be seen as a response to an anxiety over navigational-related interests and not a militarization in anticipation of a struggle over natural resources. Indeed, many of the recent military moves, like the reopening of a Soviet-era base in the Arctic to “ensure the security and effective work of the NSR”, are aligning with the protection of maritime spaces.10 Moreover, Moscow seems more interested to project its power by economic means than military ones because a key source of its power and influence in the world comes from its energy sector. Thus, this reduces the need for an aggressive posture.11

Conclusion

In conclusion, Russia relied on international law and cooperation in the Arctic through different periods of its history. Today, Russia is still a strong supporter of the UNCLOS as a tool to resolve regional disputes and insists upon the scientific basis of its territorial claims. According to Dmitri Trenin, Russia bases its Arctic strategy upon international law and agreements, and its actions in the Arctic may have seemed aggressive in part because they occurred in a context of worsening relations with the West. Russia may oppose Western objectives, but there is a stated commitment to international law and Russia “has shown itself a committed, rule-abiding participant”.12 Moreover, Russia’s current interests in the region do not seem to promote an aggressive posture because they concern principally the economic sector. As 97 percent of the region’s oil and gas deposits are found in undisputed EEZ seabed of littoral states, with the Russian EEZ accounting for 80 percent of the gas, the risk of conflict around natural resources in the High North is likely to remain limited.13

Laguerre Corentin has a M.A. in War Studies from King’s College London and presently works as a research assistant at the Institut de Recherche Stratégique de l’Ecole Militaire (IRSEM), which depends from the French Ministry of Defense.

Read other contributions to Russia Resurgent Topic Week.

[otw_shortcode_button href=”https://cimsec.org/buying-cimsec-war-bonds/18115″ size=”medium” icon_position=”right” shape=”round” color_class=”otw-blue”]Donate to CIMSEC![/otw_shortcode_button]

1 Alexander Sergunin & Valery Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, Defense & Security Analysis 30:4 (2014), 327

2 Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”,76-78

3 Idem, 80

4 Idem, 80-82, 86-87

5 Sergunin & Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, 324, 326

6 Kari Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21:2 (2015), 119

7 Sergunin & Konyshev, “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”, 327

8 Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, 119

9 Idem, 116-119

10 Lincoln E. Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 28:1 (2015), 91-92

11 Roberts, “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”, 116-118

12 Idem, 114, 116

13 Flake, “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”, 89

Bibliography

Flake, Lincoln E. 2015. “Forecasting Conflict in the Arctic: the Historical Context of Russia’s Security Intensions”. The Journal of Slavic Military Studies 28:1, 72-98

Roberts, Kari. 2015. “Why Russia Will Play By the Rules in the Arctic”. Canadian Foreign Policy Journal 21:2, 112-128

Sergunin, Alexander & Konyshev, Valery. 2015. “Is Russia a Revisionist Military Power in the Arctic?”. Defense & Security Analysis 30:4, 323-335

The Russian bear