By Josh Abbey

Few navies are disposed to undertake ship-to-shore movement in a contested environment.1 With the exception of very powerful nations such as the U.S., few nations have the number of troops and equipment necessary for success against moderate opposition. Contested ship-to-shore movement presupposes that landing craft and aircraft will be engaged while moving to and at the landing location. Achieving air and naval superiority is a significant factor in this calculus, however, so does the size and firepower of the landing force and those who may oppose them.2 The role of quantity in contested ship-to-shore movement undertaken by surface craft is especially key.

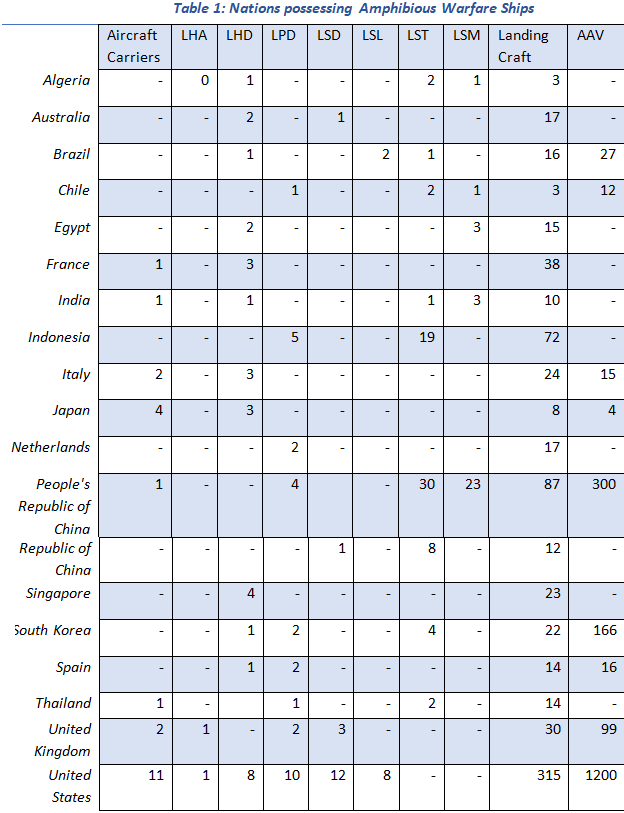

No amphibious force is likely to survive a contested assault without significant losses.3 Yet few can deliver the volume of troops to generate force overmatch against a foe while accounting for potential casualties. The majority of amphibious fleets are too small to generate overmatch by quantity alone. Such a task requires vast amphibious fleets. In the Gulf War, it took 31 amphibious ships to muster an assault force of 17,800 marines, 39 tanks, 96 mobile TOW antitank missile systems, 112 amphibious assault vehicles, 52 light armored vehicles, 52 artillery pieces, 63 attack aircraft, and six infantry battalions.4 Excluding the U.S., for nations with amphibious capabilities, the average amphibious fleet size is just two ships (refer to table 1).5 An amphibious fleet such as Australia’s can only embark 2,600 troops in two Canberra-class landing helicopter docks and one dock landing ship, HMAS Choules.6 An unsupported landing force of this size would face a serious struggle if opposed by even a few battalions.

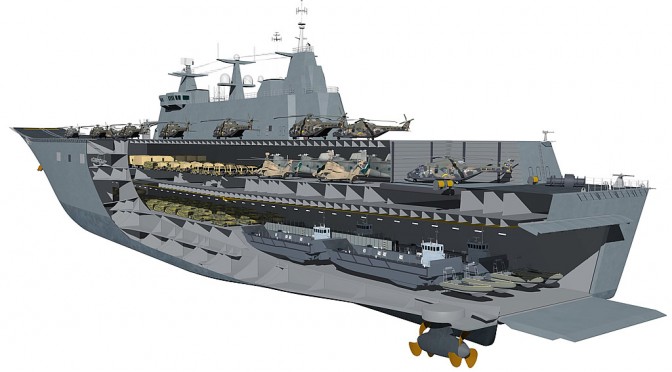

The number of troops and vehicles that can be delivered per wave severely worsens the problem of successful ship-to-shore movement. Again, Australia’s amphibious capacity shall serve as the example as its three-ship Amphibious Ready Group is representative of many first-rate nations’ amphibious fleets. A Canberra-class warship can embark four LCM-1Es, whilst HMAS Choules can carry one LCM-1E.7 With each LCM-1E able to carry 170 troops, the nine LCM-1Es can deploy approximately 1500 troops in one wave.8 However, it is unlikely they would be utilized in this way. Carrying vehicles and equipment in waves while deploying troops in tactical formations would likely decrease the rate of troops delivered. Defenders can likely bring a greater proportion of their force to bear compared to amphibious troops that are limited by their rate of delivery. And, while vehicles such as an Abrams tank or even a Stryker can deliver considerable firepower, they must be able to get off the beach to make way for follow-on assets. Beaches can condense landing troops into denser formations and where targeting buildup locations will be a priority for any defender. Unless the landing location is suitable to allow vehicles to quickly get off the beach, they present attractive stationary targets that are less able to influence affairs much beyond the shoreline.

Infantry will play a major role in the initial ship-to-shore movement because of greater freedom of movement and ability to disperse. However, embarked troops do not equate to immediate combat manpower on the beach. It is problematic that troops must disembark and find a favorable tactical disposition before they can bring their full influence to bear, a process that is unlikely to be as rapid as desired. Further, utilizing landing craft with high capacities such as LCMs, with a capacity of 170, or an LCU 1700 which can carry 350 troops, presents a small number of highly dense targets.9 If it only deployed from embarked landing craft Australia’s entire amphibious landing force could present just nine targets. An opponent could counter this force before it lands with a handful of guided missiles or several accurate barrages of cluster or airburst artillery.

While landing craft and amphibious fleets can deploy a reasonable number of troops from the surface they can be effectively opposed by far fewer troops using modern weapons. Utilizing smaller landing craft in greater numbers would increase the number of targets an enemy must account for, and dilute a defender’s efforts. Increasing the number of landing craft also decreases the time it takes for troops to influence combat by speeding up debarkation. In effect, increasing the number of exits can increase the space through which troops can disembark and achieve greater flow of deployment. These changes would increase the effectiveness of the force embarked by deploying them into combat faster and likely with less casualties.

Conclusion

Quite simply to generate overmatch via the quantity of troops amphibious fleets must go big or go home. They also, by way of contradiction in terms of landing craft, must go little if they wish to quickly generate a reasonable number of combat-ready troops at the landing location rapidly. Small numbers of slow-deploying troops can easily be victim to defeat in detail. Generating overmatch at the landing location will then be more a matter of greater firepower and less the the quantity of assets for navies with small amphibious fleets. However, credibly confronting reasonably-sized adversaries in a contested ship-to-shore context will be limited to coalition operations or large nations such as the U.S. for the foreseeable future.

Part 2 of this series will focus on firepower overmatch.

Josh Abbey is a research intern at the Royal United Services Institute of Victoria. He is studying a Bachelor of Arts at the University of Melbourne, majoring in history and philosophy. He is interested in military history and strategy, international security and analyzing future trends in strategy, capabilities and conflict.

References

1. See Table 1.1

2. Michael Hanlon, “Why China Cannot Conquer Taiwan,” International Security 25, 2 (2000): 4.

3. B. Martin, Amphibious Operations in Contested Environments: Insights from Analytic Work (Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation, 2017), 9.

4. Michael F. Applegate, Naval Forces: Valuable Beyond the Sum of Their Parts (Newport, RI: Naval War College, 1993), 5.

5. See Table 1.1

6. Ken Gleiman and Peter Dean, Beyond 2017: the Australian Defence Force and amphibious warfare (Canberra: APSI, 2015), 24.

7. “Amphibious Assault Ship (LHD),” Navy, accessed July 25, 2018, http://www.navy.gov.au/fleet/ships-boats-craft/lhd. “HMAS Choules,” Navy, accessed July 24, 2018, http://www.navy.gov.au/hmas-choules.

8. “Lanchas de desembarco LCM-1E” Navantia, accessed July 24, 2018, https://www.navantia.es/ckfinder/userfiles/files/lineas_act/Fichas_antiguas%20espa%C3%B1ol/lanchas.pdf.

9. “Landing Craft, Mechanized and Utility – LCM / LCU,” America’s Navy, accessed July 25, 2018, http://www.navy.mil/navydata/fact_display.asp?cid=4200&tid=1600&ct=4.

Featured Image: 180729-M-FA245-1234 MARINE CORPS BASE HAWAII (July 29, 2018) U.S. Marines push toward an objective on Pyramid Rock Beach during an amphibious landing demonstration as part of Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise on Marine Corps Base Hawaii July 29, 2018. (U.S. Marine Corps photo by Lance Cpl. Adam Montera)