The carrier take-off and arrested landings of the U.S. Navy’s X-47B demonstrator have garnered significant press attention this year. Less noticed however, is the rapid development of rotary-wing unmanned aerial vehicles in the world’s navies. Recent operational successes of Northrop Grumman’s MQ-8B Fire Scout aboard U.S. Navy frigates have led to many countries recognizing the value of vertical take-off and landing UAVs for maritime use.

International navies see the versatility and cost savings that unmanned rotary wing platforms can bring to maritime operations. Like their manned counter-parts, these UAVs conduct a variety of missions including intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR); cargo resupply/vertical replenishment; and in some future conflict will perform armed interdiction at sea. However, unlike the two- or three-hour endurance of manned helicopter missions, some of these UAVs can fly 12-hour sorties or longer. Other benefits include the ability for some models to land on smaller decks than manned aircraft, a much lower cost per flying hour, and importantly, limited risk to human aviators. Several international VTOL UAV projects have been recently unveiled or are under development, many of them based on proven light manned helicopter designs. Starting with a known helicopter design reduces cost and technical risks and allows navies to pilot the aircraft in no-fail situations involving human passengers such as medical evacuations.

Poland has two designs in the works, the optionally manned SW-4 SOLO and the smaller composite ILX-27, which will carry up to 300 kg in external armament. In July, the Spanish Navy announced a contract with Saab to deploy the Skeldar V-200 unmanned air system aboard its ships for counter-piracy operations in the Indian Ocean.

Russia’s Berkut Aero design bureau, in collaboration with the United Arab Emirate’s Adcom Systems have announced plans to develop an unmanned combat air vehicle (UCAV) based on Russia’s two-seat coaxial Berkut VL helicopter.

One of Schiebel’s rapidly proliferating S-100s mysteriously crashed in al-Shabaab-held Southern Somalia earlier this year, but in a successful turn-around, Camcopter S-100 conducted at-sea trials with a Russian Icebreaker in the Arctic later this summer.

Back on the American front, in July, Northrop Grumman delivered the Navy’s first improved MQ-8C, a platform largely driven by U.S. Special Operations Command’s requirements for a longer endurance ship-launched aircraft capable of carrying heavier payloads including armament. The Marine Corps’ operational experimentation in Afghanistan with two of Lockheed Martin/Kaman’s K-MAX unmanned cargo-resupply helicopters from 2011 until earlier this year was largely successful, but suspended in June when one of the aircraft crashed while delivering supplies to Camp Leatherneck in autonomous mode. Because of this setback, Lockheed has improved K-MAX’s autonomous capabilities, and added a high-definition video feed to provide the operator greater situational awareness. Kaman has also begun to market the aircraft to foreign buyers. Finally, a Navy Research Laboratory platform, the SA-400 Jackal, took its first flight this summer.

There are minimal barriers to VTOL UAVs wider introduction into the world’s naval fleets over the next few years. How much longer will it take for their numbers to exceed manned helicopters at sea?

This article was re-posted by permission from, and appeared in its original form at NavalDrones.com.

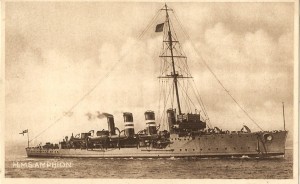

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”

Looking back at Corbett’s writings, he talks a great deal about the need for cruisers, but technology and terminology have moved on and the cruisers of Corbett’s days are not what we think of as cruisers today. Corbett’s “Some Principles of Maritime Strategy” was published in 1911. There were some truly large cruisers built in the years leading up to World War I, but Corbett decried these in that their cost was in conflict with the cruiser’s “essential attribute of numbers.”