International Maritime Satire Week Warning: The following is a piece of fiction intended to elicit insight through the use of satire and written by those who do not make a living being funny – so it’s not serious and very well might not be funny. See the rest of our IntMarSatWeek offerings here.

CAMP FUJI, JAPAN—U.S. Marine Second Lieutenant Chandler Weisenbottom graduated from a Division II school in the Southeast United States with a Bachelor’s Degree in Physical Education and was the sergeant-at-arms for his fraternity, all accomplishments that would grant him a modest head nod at any bar in America. Tragically, the Marine Corps has refused to acknowledge the depth and breadth of his brilliant capabilities.

“Listen, I took an Arabic studies elective sophomore year and learned as least three greetings. But when I showed up to the battalion, no one [expletive] cared,” said Weisenbottom as he was trying to figure out how to get the pin on his common access card (CAC) to work. Sources reported he had been at the computer for at least an hour even though he never went through the necessary check-in steps and therefore had not had his PIN loaded into the card. Weisenbottom stated that up until now he mostly used his CAC to get cheap booze from the package store on the base near his mom’s house while he waited to begin at The Basic School (TBS).

Weisenbottom was emphatic that his skills were being less than efficiently utilized.

“The semester after I came back from Platoon Leader’s Class I taught all my brothers how to lead a fire team attack on a Soviet machine gun nest so that we could teach those Delta Omega [expletives] a lesson,” said Weisenbottom, referring to the summer training program for officer candidates and a movie reference he doesn’t understand. “So I think I have some credibility when I am trying to teach my platoon how to interpret Clausewitz as it pertains to sexual assault prevention and response.”

“I mean why the [expletive] was I not put in charge of the battalion’s embedded training team? I have the cultural background for Christ’s sake—I got a C+ in that [derogatory]-studies class,” Weisenbottom cried after resigning from his attempts with the CAC. When questioned as to why the battalion would need Arabic cultural awareness when they were currently on a rotation to Japan, Weisenbottom replied “huh, well it’s still important and I need to get a [expletive] pump in before I punch out to 1STCIVDIV so I can get into finance.”

Weisenbottom’s platoon sergeant, Dave Smith, was resigned when questioned about his new platoon leader’s woes. “The LT is okay, he mostly sits around sucking up to the XO because they were in the same skull society or whatever the [expletive] at some college, so he doesn’t get in our way too much. It is problematic though when he wants to teach a class, since we have a pretty tight training schedule, and those stupid hip pocket classes keep the Marines from getting any time out in town to try and get some [derogatory] strange. [Expletive], it’ll be at most another week until some [expletive] gets us locked down again for [expletive] something up, so I better get laid.”

Captain Brent Duckler, Weisenbottom’s commanding officer, stated that the new lieutenant would be fine if “he quit [expletive] whining” about his cultural skills being misused and finished confirming “his [expletive] consolidated memorandum receipt (CMR).”

Weisenbottom was unavailable to respond to Duckler’s remarks and was reportedly busy trying to set up a Marine Corps Martial Arts Program (MCMAP) tournament that had registered only other new lieutenants.

Maynard, Cushing & Ellis is the repository of our anonymously submitted articles.

![U.S. Marine [Expletive] No One Realizes He’s the [Expletive]](https://cimsec.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/Marines.jpg)

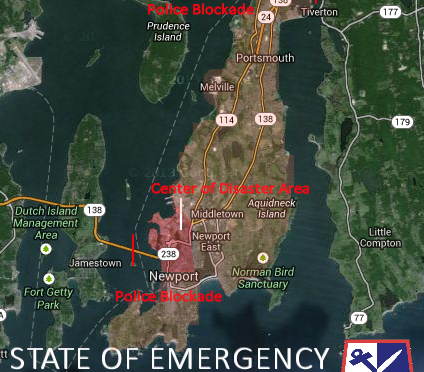

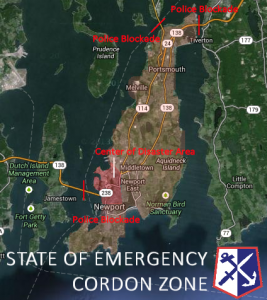

After what are being called a “series of industrial accidents,” Rhode Island Governor Henry Armitage declared a state of emergency today. Aquidneck Island has been cordoned off as a no-go zone centered around Downtown Newport and the Naval War College. General Thomas Malone of the Rhode Island National Guard has put out the call to mobilize the 56th Troop Command as well as the 43rd Military Police brigade as local and state police set up blockades on the Claiborne Newport Bridge, Mt. Hope Bridge, and Sakonnet Bridge.

After what are being called a “series of industrial accidents,” Rhode Island Governor Henry Armitage declared a state of emergency today. Aquidneck Island has been cordoned off as a no-go zone centered around Downtown Newport and the Naval War College. General Thomas Malone of the Rhode Island National Guard has put out the call to mobilize the 56th Troop Command as well as the 43rd Military Police brigade as local and state police set up blockades on the Claiborne Newport Bridge, Mt. Hope Bridge, and Sakonnet Bridge.