Just as history and past experiences have guided the People’s Republic of China (PRC) on a path towards the deployment of a robust anti-access/area-denial capability (A2/AD), Washington’s own historical narrative will guide its own counter response. Such a response, known as Air-Sea Battle (ASB), has gone through an important evolution–thanks mainly to an important and often times heated debate–over the last four years that many scholars and followers of this operational concept are quick to gloss over or are unaware of. Understanding such an evolution and tracking its progress is key not only for understanding ASB itself but also in monitoring how nations and non-state actors dependent on A2/AD might attempt to adapt or counter such efforts.

ASB: Core Foundations

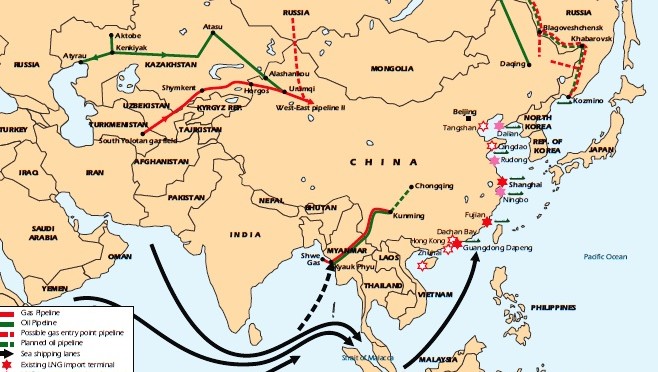

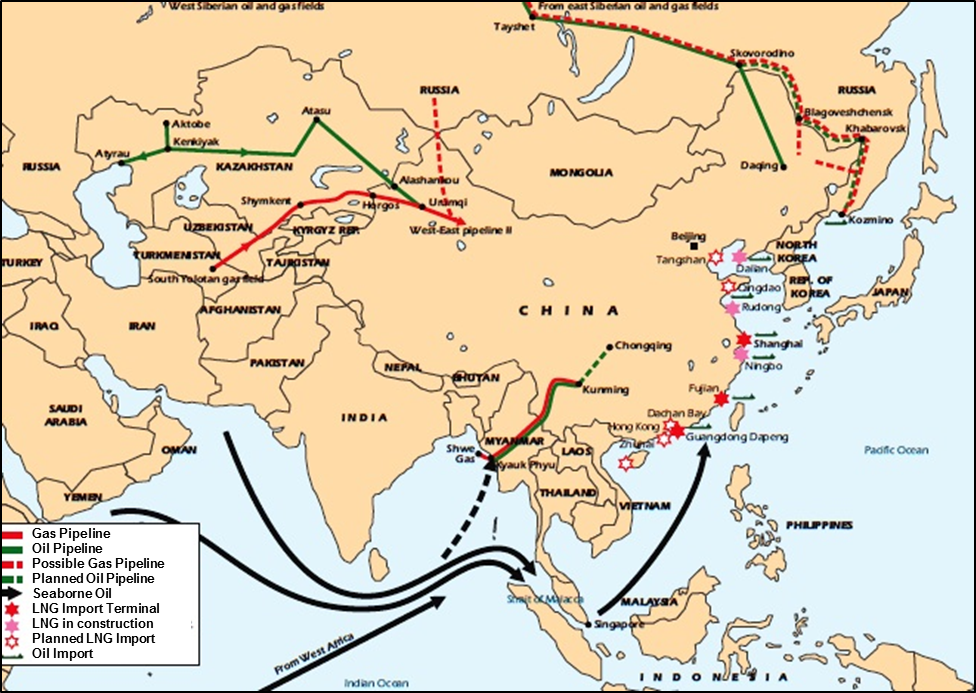

American planners over the last several years have sought techniques to continue to deploy a superior conventional military capability in spite of growing A2/AD capabilities, retain the ability to mass forces and enter a combat zone decisively while controlling the global commons across all domains (land, air, sea, space, and cyber). Despite carefully worded statements, Washington is clearly trying to negate PRC and in some respects Iran’s A2/AD capabilities along with non-state actors. The most widely discussed option when it comes to defeating A2/AD strategies is the highly controversial operational concept known as AirSea Battle. Many times confused as a war fighting strategy, in its simplest form, ASB is an effort by America’s military to ensure access to the global commons from any adversary that would contest such access across any and all domains.

The initial phrase ASB is a most likely a borrowed one. It derives its likeness from the Cold War concept of AirLand Battle (ALB). ALB was its own joint warfighting concept; however, that is largely where the similarities stop. As Robert Farley has noted, ALB succeeded Active Defense as U.S. Army doctrine in the early 1980’s. The doctrine primed NATO forces for combat in Central Europe against the Warsaw Pact, although many of its basic precepts could also apply to other scenarios (like the 1991 Gulf War, for example). Farley explains that “ALB represented an accommodation between the Army and the USAF, providing a respite to the decades of intra and inter-service strife…” The Air Force essentially set aside its own strategic concept in order to provide operational and tactical support for army forces in a protracted struggle with a much larger conventional adversary.

CSBA Version of Air-Sea Battle: ASB 1.0?

The first comprehensive study of ASB and what it could offer U.S. war planners is a widely cited 2010 report from the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA) entitled: AirSea Battle – A Point of Departure Operational Concept. To this day, the report is one of the most authoritative documents concerning ASB, even though the concept has evolved dramatically since publication. While the document was developed without Department of Defense support, it provides important detailed operational and strategic guidance of how ASB could be moved from an operational concept into a war-fighting strategy to defeat A2/AD battle networks.

While the CSBA version addresses ASB capabilities at the tactical and strategic levels, it is the operational level that is most important, as ASB is an operational concept—which many scholars confuse. As the CSBA report notes:

Air-Sea Battle must address the critical emerging challenges and opportunities that projected Chinese A2/AD capabilities will present, and to which currently envisioned US forces do not appear to offer a suitable response. In general, since A2/AD capabilities seek to impose ever-greater constraints on US operational freedom of action, an AirSea Battle concept must address how the challenge can be offset or, failing that, how freedom of action can be regained in at least selected temporal/positional aspects for purposes of power projection.

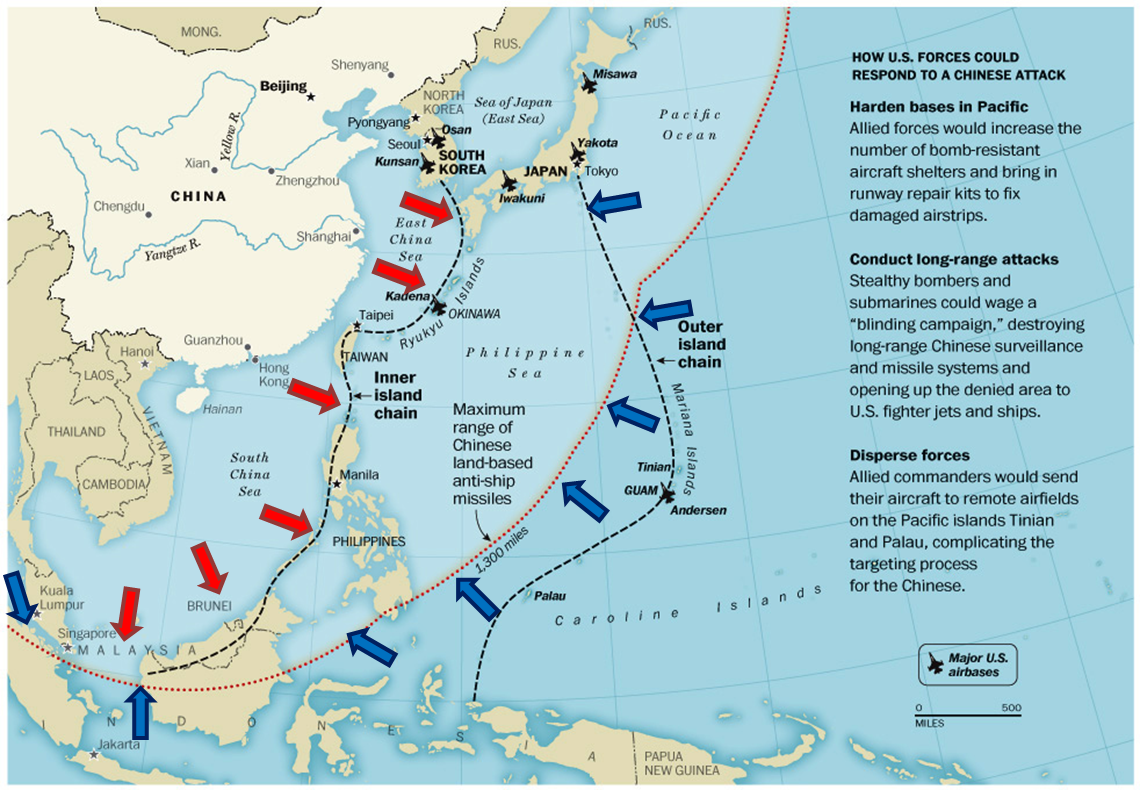

The CSBA version of ASB would see combat take place in two stages. The first stage is detailed as an initial stage, comprised of several distinct lines of operation. U.S. forces would first withstand an initial attack and limit possible damage. Next, a “blinding campaign” would commence against PLA battle networks. Next, a “suppression campaign” would then commence, focusing on PLA long-range ISR and strike systems. Focus would also be placed to ensure “Seizing and sustaining the initiative in the air, sea, space and cyber domains.” Emphasis would also be placed on “distant blockade operations,” and increased procurement and production of precision guided munitions—among other goals.

ASB would rapidly find acceptance and quickly be adopted by official U.S. war planners as part of an overall strategy to shift U.S. thinking away from COIN based operations to future military challenges—specifically operating in A2/AD environments. During late fall of 2011, it was announced that an Air-Sea Battle office was in the process of being formed to “oversee the integration of air and naval combat capabilities in an age of smaller budgets and leaner forces.”

ASB and the JOAC

ASB continued its evolution as part of a much wider Joint Operational Access Concept, or commonly known as JOAC, in early 2012. Signed by U.S. Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Martin Dempsey, the goal of this document is to show how U.S. “joint forces will operate in response to emerging anti-access and area-denial security challenges.” The JOAC places the first official U.S. definition of ASB into the public domain:

The intent of Air-Sea Battle is to improve integration of air, land, naval, space, and cyberspace forces to provide combatant commanders the capabilities needed to deter and, if necessary, defeat an adversary employing sophisticated A2/AD capabilities. It focuses on ensuring that joint forces will possess the ability to project force as required to preserve and defend U.S. interests well into the future.

Enter The ASB Office

ASB would again be refined and further sculpted once more in U.S. government documents for public disclosure, this time by the newly formed AirSea Battle office itself. On May 12, 2013, the ASB office released an unclassified version of what was dubbed a “summary” of the ASB operational concept:

A limited objective concept that describes what is necessary for the joint force to sufficiently shape A2/AD environments to enable concurrent or follow-on power projection operations. The ASB Concept seeks to ensure freedom of action in the global commons and is intended to assure allies and deter potential adversaries. ASB is a supporting concept to the Joint Operational Access Concept (JOAC), and provides a detailed view of specific technological and operational aspects of the overall A2/AD challenge in the global commons. The Concept is not an operational plan or strategy for a specific region or adversary. Instead, it is an analysis of the threat and a set of classified concepts of operations (CONOPS) describing how to counter and shape A2/AD environments, both symmetrically and asymmetrically, and develop an integrated force with the necessary characteristics and capabilities to succeed in those environments.

Confusion, Evolution and Revolution?

Even after the ASB offices authoritative documentation, many still confused ASB for a war-fighting strategy against China. Many mistakenly continue to this day cite and attack the CSBA version of ASB. The area of the document that draws the most attention is where it calls for controversial kinetic strikes on mainland China to disrupt important A2/AD C2 and C4ISR that would control PLA A2/AD combat capabilities. Because of this confusion, members of the House Armed Services Committee held a special session on October 10, 2013 in an attempt to remove any ambiguity (I was able to attend). The meeting was described as “for the first time ever, senior leaders from the Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps, Army and Joint Staff discussed the Air-Sea Battle Concept in an open hearing.” As U.S. Navy Rear Admiral James Foggo testified, ASB is:

Designed to assure access to parts of the “global commons” – those areas of the air, sea, cyberspace and space that no one “owns,” but which we all depend on – such as the sea lines of communication. Our adversaries’ anti-access/area denial strategies employ a range of military capabilities that impede the free use of these ungoverned spaces. These military capabilities include new generations of cruise, ballistic, air-to-air, and surface-to-air missiles with improved range, accuracy, and lethality are being produced and proliferated. Quiet modern submarines and stealthy fighter aircraft are being procured by many nations, while naval mines are being equipped with mobility, discrimination and autonomy. Both space and cyberspace are becoming increasingly important and contested. Accordingly the Air-Sea Battle Concept is intended to defeat such threats to access, and provide options to national leaders and military commanders, to enable follow-on operations, which could include military activities, as well as humanitarian assistance and disaster response. In short, it is a new approach to warfare.

In many respects the debate and confusion around ASB has played a critical role in its evolution and definition in publicly available sources of information. While scholars will surely battle over the abilities of ASB to provide effective solutions to confront the challenge of proliferating A2/AD technologies and strategies, having a correctly understood definition of ASB are crucial to such a debate. As ASB has been misinterpreted, misunderstood, or mistaken for something it is not, those who look to the benefits of ASB have been forced to refine and develop the motivations and aspirations of this operational concept. While issues of national strategy, budgetary politics and public opinion may ultimately cause ASB to become nothing more than an historical curiosity (for the record, I sure hope not) its evolution continues on for those who wish to see it.

Harry J. Kazianis is a non-resident Senior Fellow at the China Policy Institute (University of Nottingham) as well as WSD Handa Fellow at the Center for Strategic and International Studies: PACNET. Mr. Kazianis also serves as Managing Editor for the National Interest. He previously served as Editor of The Diplomat. The views expressed are his alone.