This is the first installment in a series of primers produced in partnership with The Diplomat.

“Words have meanings.” It’s easy to dismiss this statement as a truism. But words – and their meanings – do hold particular import in the multi-layered realm of maritime territorial disputes, where the distinction between a rock and an island can mean the difference between hundreds of square miles of Exclusive Economic Zone. At times, usage of words has itself opened new fronts in conflicts as nationalist fights over place names in textbooks have shown. Those wishing to understand and accurately describe maritime Asia’s long-standing territorial disputes must wade through a colorful and evolving vocabulary. So, in an effort to help bring clarity to the lexicon we offer this guide to common terms in use.

A Starter Legalese

U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): UNCLOS is the international agreement that resulted from the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea from 1973-1982. It establishes the maritime zones that divide the modern seas, and the rights and sovereignty of states within them. It also provides means for determining sovereignty within disputed areas. The United States has neither signed nor ratified UNCLOS but regards all but several clauses relating to the International Seabed Authority as customary international law that it therefore follows. Several additional key international terms below are defined in UNCLOS. A full reading of the Convention is highly recommended for any serious student of international affairs to gain a better appreciation of the nuances of the terms than can be spelled out here:

U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS): UNCLOS is the international agreement that resulted from the Third UN Conference on the Law of the Sea from 1973-1982. It establishes the maritime zones that divide the modern seas, and the rights and sovereignty of states within them. It also provides means for determining sovereignty within disputed areas. The United States has neither signed nor ratified UNCLOS but regards all but several clauses relating to the International Seabed Authority as customary international law that it therefore follows. Several additional key international terms below are defined in UNCLOS. A full reading of the Convention is highly recommended for any serious student of international affairs to gain a better appreciation of the nuances of the terms than can be spelled out here:

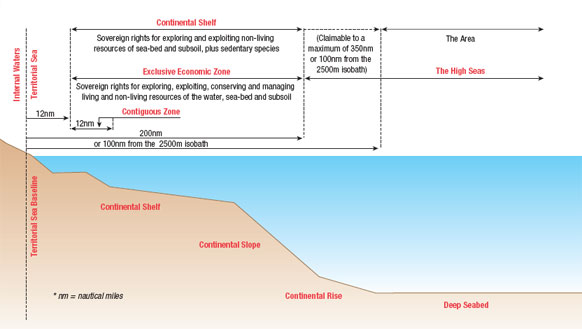

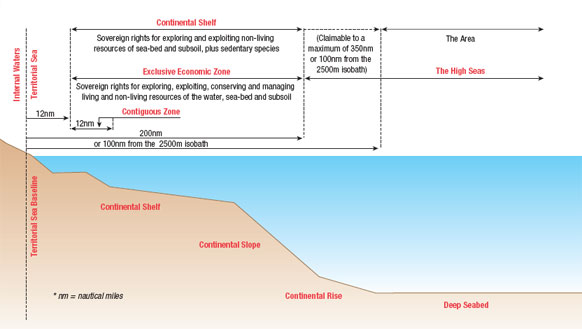

Territorial Waters: Extends 12nm from a country’s internationally agreed upon baseline. A coastal state has full sovereignty over its territorial waters, but other states’ vessels (including military, but not aircraft) enjoy the Right of Innocent Passage through these waters so long as their passage is “continuous and expeditious,” and not “prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State.” For example naval vessels cannot engage in spying during the transit and submarines must transit surfaced. A similar concept is that of Transit Passage, enabling the “continuous and expeditious” passage of all ships and aircraft through most international straits, as well as archipelagic states’ sea lane passages (straits formed by two islands of the same state).

Contiguous Zone: Extends from 12nm out to 24nm from a country’s baseline. Coastal states here enjoy rights limited to “customs, fiscal, immigration [and] sanitary laws and regulations.”

Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ): Extends 200nm out from the baseline, wherein a state enjoys exclusive rights to natural resources such as fish and oil. States may also enjoy some resource exploitation rights in the seabed and subsoil beyond the EEZ depending on the lay of the Continental Shelf.

Artificial Islands: Of importance due to recent activity in the South China Sea, “Artificial islands, installations and structures do not possess the status of islands. They have no territorial sea of their own, and their presence does not affect the delimitation of the territorial sea, the exclusive economic zone or the continental shelf.”

High Seas: Anything beyond a state’s EEZ. “No State may validly purport to subject any part of the high seas to its sovereignty.” The high seas are sometimes also referred to synonymously as International Waters, but this latter term is not well defined as it can also be used for everything outside a nation’s territorial waters. Note: Per UNCLOS, Piracy can technically occur only on the high seas or “in a place outside the jurisdiction of any state,” such as the waters of a failed state. This is why reporting of piracy statistics can be inaccurate unless it uses the term Piracy and Armed Robbery to capture piracy occurring within a nation’s EEZ.

The Freedom of Navigation: The overarching right of ships (and aircraft with Freedom of Overflight) to transit the sea unimpeded except as restricted by international law. Some states, such as China, claim rights not afforded to it by UNCLOS or customary international law, namely the ability to restrict activities of military assets and aircraft not inbound within its contiguous zone and EEZ (see for example the recent dispute over the right of U.S. P-8 Poseidon aircraft to fly outside of its territorial waters). The United States conducts Freedom of Navigation operations to register its non-concurrence with China’s position on territorial rights, thereby preventing it from becoming accepted customary international law.

ITLOS (International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea): Established by UNCLOS, its mandate is to “adjudicate disputes arising out of the interpretation and application of the Convention.” The Philippines has a case before the tribunal asking it to declare China’s Nine-Dash Line not in accordance with UNCLOS (and therefore not a valid basis for its South China Sea claims) – the ruling is expected in the next two years, but China is not taking part in the proceedings and has indicated it will not abide by the ruling.

Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ): According to Foreign Affairs, an ADIZ is “a publicly defined area extending beyond national territory in which unidentified aircraft are liable to be interrogated and, if necessary, intercepted for identification before they cross into sovereign airspace.” An ADIZ is not covered by any international agreement and does not confer any sovereignty over airspace or water, but has arguably become a part of customary international law due to its growing usage and acceptance. The rules China stipulated with its establishment of an ADIZ in the East China Sea in late 2013 however garnered widespread criticism and non-observation due to its surprise announcement and application to those flights not intending to enter sovereign airspace.

Conduct for Unplanned Encounters at Sea (CUES): CUES provides a set of non-binding “safety procedures, a basic communication plan and basic maneuvering instructions” when naval vessels and aircraft unexpectedly encounter each other at sea. It was agreed upon at the 14th Western Pacific Naval Symposium in April 2014, and while a code of conduct CUES should not be confused with the much-discussed and as yet elusive ASEAN Code of Conduct below.

Code of Conduct (CoC): In 2002, the member states of ASEAN and China signed a voluntary Declaration on the Conduct (DoC) of parties in the South China Sea “to resolve their territorial and jurisdictional disputes by peaceful means, without resorting to the threat or use of force, through friendly consultations and negotiations by sovereign states directly concerned.” This was to be the precursor to a binding CoC, but as Carl Thayer ably documents implementation of the CoC was kept in check for a decade by China and focus on Guidelines to Implement the DoC, which were approved in 2012. However, promises in the DoC such as to refrain from then uninhabited maritime features and to handle differences in a constructive manner have since been violated by actions including several parties’ ongoing construction and expansion on features under their control. As a result of this and because the Guidelines have been removed as the focus by adoption, many ASEAN states, with the Philippines foremost among them, have returned attention to reaching agreement on a legally binding CoC. There have been recent indications that China may be willing to soon start serious discussions about the Code of Conduct, but it is unclear whether it will be willing to accede to (let alone adhere to) any potent enforcement mechanisms.

A Strategic Buffet

Cabbage Strategy: In a television interview in May, People’s Liberation Army (PLA) Maj. Gen. Zhang Zhaozhong described China’s approach towards securing control over and defending the Scarborough Shoal, after reneging on an agreement with the United States whereby both they and the Philippines would back down from a standoff in 2012:

Surrounding a contested area with so many boats — fishermen, fishing administration ships, marine surveillance ships, navy warships — that “the island is thus wrapped layer by layer like a cabbage.”

Analysts note this approach forces those opposing China’s actions to contend not only with layers of capabilities but also rules of engagement and public relations issues such as would arise from a confrontation between naval vessels facing fishing boats at the outermost layer. A more recent example of this layered approach occurred this summer with the arrival of a CNOOC oil rig in Vietnam’s claimed EEZ.

Analysts note this approach forces those opposing China’s actions to contend not only with layers of capabilities but also rules of engagement and public relations issues such as would arise from a confrontation between naval vessels facing fishing boats at the outermost layer. A more recent example of this layered approach occurred this summer with the arrival of a CNOOC oil rig in Vietnam’s claimed EEZ.

Salami Tactics (A.K.A. Salami Slicing): This term was coined by Hungary’s Cold War Communist ruler Matyas Rokosi to depict his party’s rise to power in the 1940s. The emphasis is on incremental action. In the initial usage it described the piecemeal isolation and destruction of right wing, and then moderate political forces. In maritime Asia it has come to be used to describe China’s incremental actions to assert sovereignty over areas of disputed territory. A key aspect of Salami Tactics is the underpinning rationale that the individual actions will be judged too small or inconsequential by themselves to provoke reaction strong enough to stop further moves.

The Three Warfares: The Three Warfares is a concept of information warfare developed by the PLA and formally approved by China in 2003 “aimed at preconditioning key areas of competition in its favor.” The U.S. DoD defined the three as:

- Psychological Warfare: Undermining “an enemy’s ability to conduct combat operations” by “deterring, shocking, and demoralizing enemy military personnel and supporting civilian populations.”

- Media Warfare: “Influencing domestic and international public opinion to build support for China’s military actions and dissuade an adversary from pursuing actions contrary to China’s interests.”

- Legal Warfare (also known as Lawfare): Using “international and domestic law to claim the legal high ground or assert Chinese interests. It can be employed to hamstring an adversary’s operational freedom and shape the operational space.” This type of warfare is also tied to attempts at building international support.

Anti-Access / Area Denial (A2/AD): describes the challenges military forces face in operating in an area. According to the U.S. DoD A2 affects movement to a theater: “action intended to slow deployment of friendly forces into a theater or cause forces to operate from distances.” AD, meanwhile, affects maneuver within a theater: “action intended to impede friendly operations within areas where an adversary cannot or will not prevent access.” Advances in weapons such as mines, torpedoes, submarines, and anti-ship missiles are commonly cited examples of those that can be used for A2/AD.

Anti-Access / Area Denial (A2/AD): describes the challenges military forces face in operating in an area. According to the U.S. DoD A2 affects movement to a theater: “action intended to slow deployment of friendly forces into a theater or cause forces to operate from distances.” AD, meanwhile, affects maneuver within a theater: “action intended to impede friendly operations within areas where an adversary cannot or will not prevent access.” Advances in weapons such as mines, torpedoes, submarines, and anti-ship missiles are commonly cited examples of those that can be used for A2/AD.

Air-Sea Battle (ASB): A warfare concept designed by the United States military to counter A2/AD challenges and ensure freedom of action by trying to “integrate the Services [primarily the Navy and Air Force] in new and creative ways.” ASB is not a “strategy or operational plan for a specific region or adversary.” There has been much debate and confusion about ASB, in part because it requires the development and balancing of new complimentary capabilities, many of them classified.

Offshore Control: A strategy for the United States to win in the event of a conflict with China put forward in 2012 by USMC Col. T.X. Hammes (Ret.). In Offshore Control, the United States focuses on bringing economic pressures to bear via a tailored blockade, working with and defending partners along the first island chain rather than strikes against mainland China.

Four Respects: The Four Respects is a new term fellow The Diplomat contributor Jiye Ki, based on remarks made by Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi earlier in September. They are the four guiding principles by which Wang says South China Sea negotiations should proceed, namely:

- The dispute over the Spratlys “is a problem left over by history,” and that “handling the dispute should first of all respect historical facts.”

- “Respect international laws” on territorial disputes and UNCLOS.

- Direct dialogue and consultation between the countries involved should be respected as it has proven to be the most effective way to solve the dispute.

- Respect efforts that China and ASEAN have made to jointly maintain peace and stability. Wang says China hopes countries outside the area can play constructive roles.

Mutual Economic Obliteration Worldwide (MEOW): A term coined by yours truly to describe the deterrent effect of the threat of economic side-effects of a conflict between the United States and China on their actions towards each other.

See any we missed? Part 2 will cover the Geography of Asian Maritime Disputes

Scott Cheney-Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He is the founder and president of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College, and a member of the Truman National Security Project’s Defense Council.

This week we concluded our campaign on Kickstarter and we could not be happier, having successfully met our goal and then some. So we want to take a brief pause from writing about drones, pirates, and tanker traffic and thank our readers, our contributors, our promoters, and especially our backers.

This week we concluded our campaign on Kickstarter and we could not be happier, having successfully met our goal and then some. So we want to take a brief pause from writing about drones, pirates, and tanker traffic and thank our readers, our contributors, our promoters, and especially our backers.