Notes from the U.S. Naval Institute’s Defense Forum Washington 2014

Last week I attended the U.S. Naval Institute’s Defense Forum Washington 2014 – “What Does the Nation Need from its Sea Services?,” which was well attended by fellow CIMSECians. Speakers included legislators, senior researchers, and representatives from the U.S. Navy, U.S. Marine Corps, and U.S. Coast Guard. The full videos of the speakers and an in-depth recap are available here, but I wanted to touch briefly on a few items that stood out.

Acting Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Plans, Policy, and Operations, RADM Kevin Donegan, did a good job articulating the questions the sea services have wrestled with in building the forthcoming maritime strategy document known as CS-21R, the revision to the 2007 A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (CS-21). While he didn’t reveal most of the answers to those questions he did acknowledge the conflicting views of what the document should be, or look like. and the difficulty in getting it on the streets, but said it would be published “very soon.” RADM Donegan did note that the underlying assumptions of 2007 in some cases no longer hold true, with a nod to the threats facing Europe. One item he did reveal was that Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Response (HA/DR) would remain a prioritized mission, something that has been questioned since its inclusion in CS-21, although whether this has a practical impact on budgeting priorities is itself debatable.

Acting Deputy Chief of Naval Operations for Plans, Policy, and Operations, RADM Kevin Donegan, did a good job articulating the questions the sea services have wrestled with in building the forthcoming maritime strategy document known as CS-21R, the revision to the 2007 A Cooperative Strategy for 21st Century Seapower (CS-21). While he didn’t reveal most of the answers to those questions he did acknowledge the conflicting views of what the document should be, or look like. and the difficulty in getting it on the streets, but said it would be published “very soon.” RADM Donegan did note that the underlying assumptions of 2007 in some cases no longer hold true, with a nod to the threats facing Europe. One item he did reveal was that Humanitarian Assistance/Disaster Response (HA/DR) would remain a prioritized mission, something that has been questioned since its inclusion in CS-21, although whether this has a practical impact on budgeting priorities is itself debatable.

There was also some discussion about the manner in which CS-21R will be rolled out to the country, with one audience member asking if there would be educational outreach efforts and town hall meetings – useful components in explaining both the content and its relevance to the American public. But those lines of effort must be just the beginning. If CS-21R is to have the impact that it should, and presuming of course that one agrees with the strategy therein, the release of this document necessitates a full public affairs and internal education campaign plan. This is an important opportunity for the sea services to make their case to the people, Congress, “decision makers,” and their own folks that supporting the nation’s (as Ron O’Rourke put it in a later presentation) maritime strategy must be a priority. In telling the story of why resourcing the Navy, the Coast Guard, and the Marine Corps (as well as other maritime components) should take precedence over other funding priorities, the strategy document owns the part that gives a coherent explanation of what the services want to do with the means requested and why these are the best ways to achieve the ends defined by higher strategic guidance. Luckily there are plenty of recent anecdotes to illustrate the arguments, as VADM Donegan pointed out the practical importance of seapower in the recent Libyan and anti-ISIS campaigns.

A few other items I found interesting:

– CIMSECian ENS Chris O’Keefe asked about both the proper role of and forum for discussing cyber in strategy and was told by the panelists that the answer was cross-cutting in both role and the forum (i.e. blogs, publications, and internal classified discussions).

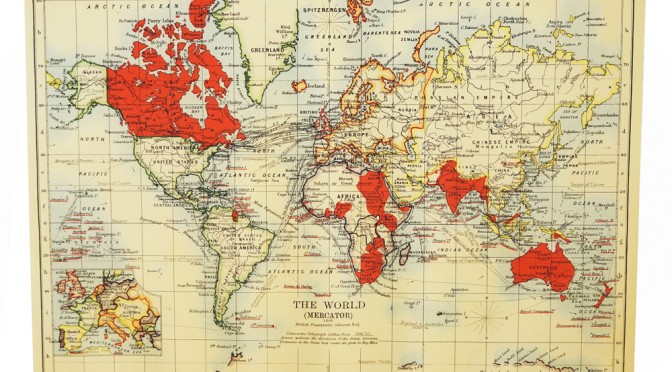

– RADM Donegan used the term “Indo-Asia-Pacific,” echoing the term “Indo-Pacific” that has in the past two years come into more common usage (typically in place of Asia-Pacific) and views the space stretching from the Indian Ocean through the Pacific as a linked geopolitical concept, particularly in maritime terms.

– The Coast Guard rep, VADM Charles Michel, Deputy Commandant for Operations, noted that the lack of arctic icebreakers hinders not only polar missions but also the ability to clear ice from the Great Lakes and U.S. coasts, forcing a reliance on Canada’s fleet.

– The Marine Corps rep, Brig. Gen. Joseph Shrader, Commander, Marine Corps Systems Command noted that the recently released Expeditionary Force 21 concept requires establishing advance bases for short take-off, vertical launch aircraft operations such as the F-35B.

– The Coast Guard and Marine Corps reps both said that the hardest challenge their Service faces is in balancing the funding needs of readiness and recapitalization (overhauling kit/modernization). Both however gave no indication that intellectual recapitalization was part of this primary concern.

Over at Chuck Hill’s CG Blog, CIMSECian Chuck takes a look at what was notable from a U.S. Coast Guard perspective, noting that VADM Michel “was the Coast Guard representative on the panel discussion…and did a credible job of representing the Coast Guard.” One of the highlight quotes came in the Q+A session of that panel when, pressed by a reporter for an example of something that the Coast Guard could not do due to budget limitations, VAdm Michel pointed to his time as director of Joint Interagency Task Force-South (JIATF-S). He stated that the lack of vessels to interdict smugglers meant that for 75% of shipments he received intelligence on he could only watch them go by. Chuck goes on to say, in the post entitled “Coast Guard in a Death Spiral?”

Over at Chuck Hill’s CG Blog, CIMSECian Chuck takes a look at what was notable from a U.S. Coast Guard perspective, noting that VADM Michel “was the Coast Guard representative on the panel discussion…and did a credible job of representing the Coast Guard.” One of the highlight quotes came in the Q+A session of that panel when, pressed by a reporter for an example of something that the Coast Guard could not do due to budget limitations, VAdm Michel pointed to his time as director of Joint Interagency Task Force-South (JIATF-S). He stated that the lack of vessels to interdict smugglers meant that for 75% of shipments he received intelligence on he could only watch them go by. Chuck goes on to say, in the post entitled “Coast Guard in a Death Spiral?”

But I would like to particularly recommend a portion of the presentation by Ron O’Rourke, who is the Congressional Research Service. He devoted the last few minutes of his presentation to the Coast Guard, beginning about minute 24:30. He does a better job of explaining the crisis in Coast Guard budgeting than I have ever seen done by any Coast Guard representative.

Looking at some of the other speakers, I learned that they have taken the program to replace the Ballistic Missile Submarine Force out of the regular navy shipbuilding budget. I think this is significant, because the effect of the SSBN replacement on the Navy ship building budget, is very similar to the effect of the heavy icebreaker procurement on the Coast Guard budget. Perhaps this might be used as a precedence for a special, separate appropriation for the icebreaker.

Scott Cheney-Peters is a surface warfare officer in the U.S. Navy Reserve and the former editor of Surface Warfare magazine. He is the founder and president of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC), a graduate of Georgetown University and the U.S. Naval War College, and a member of the Truman National Security Project’s Defense Council.

An academic (Dr. Alexander Clarke), an operator (Cdr Paul

An academic (Dr. Alexander Clarke), an operator (Cdr Paul