ADM John Harvey, USN (ret), joins us to discuss the Third Offset and the “Human Offset.” Third Offset is Defense Undersecretary Robert Work’s strategy to embraces the US technological advantage, pushing the throttle to the max through a suite of development efforts. However, ADM Harvey worries that this technological emphasis will pull attention from other foundational areas – like talent management and development – as well as what he sees as a dedication of our resources into dominance less-achievable in our globalized civilian-led tech economy.

ADM John Harvey, USN (ret), joins us to discuss the Third Offset and the “Human Offset.” Third Offset is Defense Undersecretary Robert Work’s strategy to embraces the US technological advantage, pushing the throttle to the max through a suite of development efforts. However, ADM Harvey worries that this technological emphasis will pull attention from other foundational areas – like talent management and development – as well as what he sees as a dedication of our resources into dominance less-achievable in our globalized civilian-led tech economy.

CIMSEC’s June NY Meet-up

Join our New York chapter for its June informal meet-up/happy hour. Members Ankit Panda and Stephen Brooker will lead a discussion on the South China Sea. We hope you’ll drop by for drinks and discussions with friends old and new.

Join our New York chapter for its June informal meet-up/happy hour. Members Ankit Panda and Stephen Brooker will lead a discussion on the South China Sea. We hope you’ll drop by for drinks and discussions with friends old and new.

Time: Thursday, 18 June 5:45pm

Place: Bedford Falls (Backyard)

206 E 67th St NW

New York City, NY

All are welcome – RSVPs not required, but appreciated: newyork@cimsec.org

The Sea Power of the State in the 21st Century

Admiral Sergei S. Gorshkov’s legacy as a naval leader and strategic thinker has not been entirely forgotten. Reports of his death, however, were not greatly exaggerated. Largely ignored by the NATO navies that once studied him so intently as the head of the Soviet Navy for much of the Cold War, Gorshkov remains an inspirational symbol in the two countries that should come as no surprise: Russia and China.

Earlier this year, Admiral Viktor Chirkov, the current commander-in-chief of the Russian Navy, pointedly chose the 105th anniversary celebration of Gorshkov’s birthday in his childhood home of Kolomna to make some bold statements about the navy’s future in the 21st century. After laying flowers at Gorshkov’s monument, Chirkov formally announced that Russia will be back in the aircraft carrier business with plans to build a new-generation one comparable in size to a U.S. supercarrier. Given the current state of Russian shipyards and the tremendous costs involved, defense analysts greeted the announcement with skepticism. There was good reason to doubt this most recent news: Russia had already announced in 2005, and again in 2008, that it would begin to build carriers by 2010. According to Jane’s Defence Weekly, the new multipurpose, dual-design (two ski-jump ramps and electromagnetic catapults each) carrier is called Project 23000E or Shtorm (Storm).

17th-19th C. Sea Power of the State: Admiral Chirkov getting a tour of USNA Museum in 2013 from CIMSEC member Claude Berube. Was the Russian navy chief trying to get advance info on the #CarrierDebate? (Photo credit: USNA PAO)

17th-19th C. Sea Power of the State: Admiral Chirkov getting a tour of USNA Museum in 2013 from CIMSEC member Claude Berube. Was the Russian navy chief trying to get advance info on the #CarrierDebate? (Photo credit: USNA PAO)

Of course, Admiral Gorshkov once promoted the virulent anti-carrier stance of the Soviet Union. He mocked the platform as too expensive and too vulnerable and echoed Premier Nikita Khrushchev’s view that they were “floating coffins.” Yet, the Soviet Navy’s need to be untethered from the sole support of land-based naval aviation first resulted in helicopter carriers for anti-submarine warfare and amphibious operations in 1967, then eventually in large-deck carriers for fixed wing aircraft toward the end of the Cold War – the Kuzntesov (still in service, although with considerable time in the repair dock, in the Russian fleet) and the Gorshkov (sold to India).

Gorshkov would likely have applauded Chirkov’s ambitious 50 ship building plan for 2015 that included a mixture of surface and subsurface vessels. In particular, the resurgence of nuclear submarine production, especially the Borei-class ballistic missile sub, is a reminder of how Gorshkov once used submarines as the cornerstone of Soviet naval power and prestige for decades.

Chirkov also announced that 30 ships and submarines were currently deployed around the world, which indicated a modest but nonetheless significant return to the pattern of out-of-area patrols and presence missions for the Soviet Navy that Gorshkov introduced to much fanfare in the mid-1960s. This May’s joint Russian-Chinese naval exercises in the Mediterranean also supports the views that the Russian Navy is “rebalancing” to the region while the Chinese Navy may intend to secure its energy supply lines at the western edge of the “New Silk Road.”

Above all, Gorshkov would probably have approved of Chirkov’s vision: the adoption of an “ocean strategy” that will seek to reestablish Russia’s global reach and promote its political and economic interests. Chirkov’s choice of language harkened back to the efforts of his Cold War-era predecessor to justify a blue-water navy. Notably, Chirkov did not directly challenge the supremacy of the U.S. Navy as Gorshov did in the late 1960s. Rather, Admiral Chirkov’s mission, at least for the moment, is to put Russian naval forces back on the path to restoration, not on one toward great power rivalry.

Gorshkov was associated with the phrase “’better’ is the enemy of ‘good enough.’” In other words, Chirkov must get the Russian Navy back to Gorshkov-era “good enough.”

There is also nothing revolutionary in Chirkov’s pronouncements. The navy’s primary missions are still, as in the Cold War, strategic deterrence and defense. It will likely not be as rapid as the transformation after the Cuban Missile Crisis, either. The Russian Navy, according to defense analyst Dmitry Gorenburg, will slowly grow through a phased recapitalization scheme that will unfold over 20 years. The pace of naval construction is, of course, subject to change based on evolving political and economic imperatives.

To further underscore that Admiral Gorshkov has not passed entirely into irrelevance, a pair of Russian military writers (one a retired navy captain) paid homage to him in a recent article for Voyennaya Mysl [Military Thought], the elite journal of Russia’s Defense Ministry for nearly a century. In “The Sea Power of the State in the 21st Century,” the authors noted that Gorshkov’s seminal 1976 book, The Sea Power of the State, took an expansive view of sea power that included naval, merchant, fishing, and exploration capabilities. Gorshkov envisioned the World Ocean as one immense domain upon which to assert Russian national power. These authors, however, wished to scope the definition of “the country’s sea power” down to “the navy’s real combat power” in order to illustrate the special place that navies hold in geopolitics.

A central theme of their essay, based on historical examples, was that countries without sea power do not have “a decisive voice in world affairs.” Russia used a strong navy in the past, the authors argued, to maintain its place in the top tier of nations. The blow to Russian prestige was great at the end of the Cold War with the demise of the Soviet Navy:

… the loss of the core of its powerful oceangoing navy during the political and economic reforms in the late 1980s and early 1990s cost the country dearly. It caused other nations, Russia’s neighbors and rivals on the high seas, in the first place, to rethink their attitude to this country. It was deserted by many allies and friends, and its image of a great sea power has faded.

Thus, the article indirectly endorsed Admiral Chirkov’s current strategy of “looking to the ocean” and his plan for a navy that can once more defend Russia’s national interests and secure it against threats. The authors acknowledged, however, the huge lead by the U.S. Navy in air-sea battle concepts and that of American expertise in network-centric naval warfare. Indeed, “it is difficult, even hopeless at times, for Russia to take up this challenge for economic considerations.” Nonetheless, they concluded, it is a price that must be paid for the return to greatness on the world stage.

Writers in Chinese open source literature have also found reasons for optimism in the example set by Admiral Gorshkov during the Cold War. According to Lyle J. Goldstein at the Naval War College’s Chinese Maritime Studies Institute, some naval analysts in China “are extremely interested in Gorshkov, his legacy, and Soviet naval doctrinal development in general” [per his correspondence with this author]. They are impressed by the rapid transformation of Soviet naval power under Gorshkov as well as his ability to check U.S. power with his own oceangoing navy. Moreover, they also appreciated, based on Gorshkov’s lesson, that a “balanced fleet” can also emphasize undersea platforms while never reaching parity with U.S. carriers.

China’s recent strategy white paper elevated the PLA Navy’s status and explicitly tied naval power to China’s geopolitical ambitions and economic development with the navy’s dual missions of “open seas protection” and coastal defense. Indeed, sea power will play a central role for the Chinese state in the 21st century:

The seas and oceans bear on the enduring peace, lasting stability and sustainable development of China. The traditional mentality that land outweighs sea must be abandoned, and great importance has to be attached to managing the seas and oceans and protecting maritime rights and interests.

On the other hand, Gorshkov’s legacy shows that sea power, once achieved, can be transitory due to geographic, economic, and political factors. His is also a cautionary tale, for Russians and Chinese alike, not to pursue sea power beyond what a nation can support. As Goldstein noted, “… the [Chinese] authors do indeed directly connect the all-out Soviet naval expansion of the later Cold War, and the commensurate enormous investment of Russian national resources, to the demise of the USSR.” Moreover, there is the potential risk involved in Russia’s attempt under Vladimir Putin to return to the past glories of the Soviet superpower era yet fall well short of his goals. This naturally includes naval ambitions for aircraft carriers that never make it beyond the concept stage. Even the modernization of smaller surface ships such as frigates (including the new Admiral Gorshov-class) is now endangered by Russian actions in the Ukraine.

Both Russia’s and China’s navies may also face the same dilemma as that of the Soviet Navy by the mid-1960s if naval construction outpaces professional knowledge and practical experience. As Robert Farley noted, the Soviet Union “built blue water ships long before it built the experience needed to conduct long range, blue water operations.” A more provocative and aggressive stance toward the U.S. Navy, coupled with the deficiencies in Soviet training and this lack of a “blue water look,” resulted in repeated incidents at sea such as collisions that many feared might escalate during the Cold War.

Ultimately, sea power as an expression of great power status is beginning to look in the early 21st century much as it did in the 20th century. The investment in costly blue-water navies still speaks volumes about a country’s geopolitical ambitions and its strategic calculus – where it sees itself in the world and hopes to be in the future. The writings and accomplishments of Admiral Sergei Gorshkov are also a timeless reminder that in order to assess navies, one must still look at what they say, what they build, and what they do. In Gorshkov’s case, what he did remains much more memorable than anything he wrote.

Jessica Huckabey is a researcher with the Institute for Defense Analyses (IDA) and a retired naval reserve officer. She is writing her doctoral dissertation on American perceptions of the Soviet naval threat during the Cold War. The opinions are her own and not those of IDA or the Department of Defense.

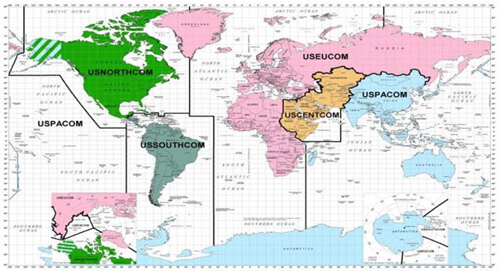

Geographic Re-balance the Solution to Right-Sizing the Navy

The new 2015 Maritime Strategy demands a significant part of the Navy be forward based or operated in order to achieve national goals. The current number of ships and their present deployment pattern may not support the new strategy’s goals. Several recent articles have bemoaned the Navy’s shrinking surface ship fleet, or sought to make light of the overall number of ships as a significant determinant of strategic naval power. Both are, in a way, incorrect. The number of ships does matter, but wishing for a return of the halcyon 1980’s and the 600 ship navy is a futile hope in the face of the present budget deficit and growing welfare state. The post World War 2 U.S. Navy deployment structure has been based on the maintenance of a specific number of total ships in order to maintain a consistent overseas naval peacetime presence and credible war fighting force if required. The solution to this combination of forward deployment requirements on a limited budget is a fundamental change to the post-1948 U.S. naval deployment scheme through a global redistribution of U.S. naval assets. Potential threats, strategic geography, and support from potential coalition partners should govern this effort. The Navy should also seek new technologies to reduce overall budget costs. If this sounds familiar, it is not a new concept. Great Britain’s Royal Navy, under the leadership of the fiery transformationalist Admiral Sir John Fisher, executed a similar successful change just over a century ago in a similarly bleak financial environment. A modified version of Fisher’s scheme represents the U.S. Navy’s best hope to assign relevant naval combat power where it is most needed and at the best cost.

Britain’s Successful Rebalance

Like the U.S. today, Great Britain at the turn of the last century was a nation in rapid relative decline. British industry and its share of the world economy were shrinking in response to the rise of Germany, Japan, and the United States. The navies of those nations, as well as traditional enemies like France and Russia were growing in size and capability. Great Britain had just concluded the financially taxing and internationally embarrassing Boer War, which strained the nation’s tax base and earned it international opprobrium for harsh treatment of Boer combatants and civilians. The concept of a British Welfare state had gained significant support, and expenditures for this new government responsibility threatened the budgets of the Army and the Navy; both of which required significant modernization.

Admiral Fisher was selected by the Conservative Party’s First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Selborne, specifically for his daring pledge to cut naval spending, while increasing the power and overall capability of the Royal Navy (RN). Fisher scrapped large numbers of older warships; created a ready reserve of minimum manned, older, but still capable combatants; reformed the RN’s personnel structure; and argued for the adoption of revolutionary technologies such as turbine engines, oil fuel for ships, director-based gun firing, submarines, and naval aircraft. A succession of Navy civilian leaders from both of the large British political parties supported his efforts. Most importantly, Fisher presided over the biggest re-balancing of British naval assets since the end of the Napoleonic wars. Before Fisher the RN was divided amongst various colonial stations around the world. Its most significant operational commands were the Atlantic and the Mediterranean Fleets that protected Britain’s line of communication to India via the Suez Canal. Although Fisher’s initial strategy was to counter France and Russia, the concentration of British naval strength in home waters allowed it to counter rising German threats. Britain sought simultaneous colonial agreements with France and Russia to reduce tension, and signed an official alliance with the emerging Japanese Empire to secure communications with its Pacific possessions. It also unofficially acquiesced to U.S. naval domination in the Western Hemisphere to eliminate any tensions with the other great English-speaking nation. All told, these efforts allowed Fisher to keep British naval spending at 1905 levels until 1911.1 They also ensured that a significant British naval force was in place for war with Germany in 1914.

Conditions for U.S. Rebalance

The U.S. would be well served to create a global re-balance program along the lines of Admiral Fisher’s for its own Navy. In reverse of Fisher, however, the bulk of America’s naval strength must move from bases in home waters to the periphery of the nation’s interests. Some reductions in overall naval strength will be required to ensure that forward forces are well trained and equipped for both peacetime presence and wartime combat functions. Assignment will depend on regional geography, threat level and the availability of coalition partners to augment, or in some case replace U.S. naval assets.

The large deck nuclear aircraft carrier and its associated air wing are best employed in locations where land-based aviation assets are vulnerable or scarce due to geographic location. For this reason, the bulk of the carrier force should be assigned to distributed bases in the Indo-Pacific region. A force of six large carriers would serve as the core of the Pacific naval component. The surface combatant and attack submarine force based in the Pacific would be a commensurate percentage of its overall strength. They should be sufficient in number to support carrier escort, independent operations, and surface action groups as recommended for the emerging strategy of distributive lethality. This force would be large enough to conduct meaningful fleet and large scale joint exercises in a number of warfighting disciplines.

The carrier’s assignment to the largest ocean area of responsibility (AOR) best supports a joint commander’s warfighting requirements in a predominately maritime environment. The caveat with the assignment of carriers geographically is that the post-1948 deployment pattern of ‘three aircraft carriers equal one forward deployed, active carrier’ must be scrapped. This means retiring two carriers, perhaps the two oldest Nimitz class when the USS Gerald R. Ford is commissioned in next year. One carrier strike group costs $6.5 million dollars a day to operate.2 The funds saved in the retirement of two carriers could be directed toward the maintenance of and operational costs of the remaining eight, with the proviso that these be consistently ready for service as required.

The Eurasian littoral areas historically supported by east coast naval forces would receive smaller, tailored force packages in this new organization scheme. Given that Eurasian littoral operations can be supported by land-based air units, only two carriers need be assigned to the Atlantic coast with perhaps a third designated as a training carrier.

A Substitute for a Carrier Strike Group

Under this arrangement the Mediterranean and Persian Gulf areas would not see regularly deployed large deck carriers. To offset their absence, it is proposed that two light carrier groups be forward-based on the Mediterranean and Indian Ocean respectively. Such a group would each be centered on an LHA-6 class amphibious warship configured as a light carrier with an airwing of 20+ F-35 Lightning II strike aircraft. The CVL-configured LHA, too small to support the full traditional carrier wing of both attack and support aircraft, would be supported by land-based assets that would provide airborne early warning (AEW), tanking, and other strike missions. Each group would contain three DDG-51 class destroyers for offensive and defensive roles including missile defense, a DDG-1000 class destroyer for surface strike and other warfare roles, and a flotilla of four to six littoral combat ships (LCS) or similar frigates (FF’s) for a variety of low intensity combat and surface strike missions. Attack submarines may be included as needed and an amphibious warfare group similar to the present 7th fleet formation based in Sasebo, Japan round out the numerical assignments. A full amphibious ready group (ARG) with associated Marine Expeditionary Force (MEU) based at Rota could exploit NATO/EU capabilities in the region as well. Most of these rebalancing efforts can be completed between 2020 and 2025, with the fight light carrier group ready by 2017. It may begin operations with the AV-8B II Harrier, but later transition to the F-35B Lightning II. After 2020, an international carrier strike group (CSG) presence might be maintained in the Eastern Mediterranean with British, French, Italian, and Spanish carriers playing a role.3

The Mediterranean offers a number of ports that together are capable of hosting such a force including Rota, Spain, Sigonella, Sicily, and Souda Bay, Crete. The Western Pacific/Indian Ocean represents a more complicated basing picture, but a combination of facilities in Singapore, Darwin, and Perth, with a forward anchorage in Diego Garcia might offer sufficient space to support to forward deployed forces. Both regions offer a number of land-based aviation facilities to support a light carrier formation.

The navies of friends and formal allies offer additional support to this strategy. The U.S. has consistently sought and depended on coalition allies in the conflicts it has engaged in since 1945, and especially since 1990. European fleets have changed from antisubmarine Cold War forces to smaller, but more deployable, larger combatants capable of global operations. Resident European force in the Mediterranean and deployed forces in the Persian Gulf region might augment U.S. efforts in those regions. The Libyan Operation of 2011 (Operation Odyssey Dawn for the U.S.), showcased what a U.S. light carrier group, as centered then on USS Kearsarge, and European forces might accomplish. The British Defence Secretary’s recent announcement that the Royal Navy will develop a base in Bahrain suggests that at least British and perhaps other Commonwealth nations’ navies might support U.S. efforts in the Persian Gulf region.

Options for Cooperation and Technological Offset

Strong U.S. relationships with Western Pacific nations are essential to any re-balancing strategy in that region. The adoption of AEGIS systems by the Japanese Maritime Self Defense Force, the South Korean, and Australian navies significantly aids in cooperative efforts. Close U.S. ties with Singapore, the Philippines, and other regional naval forces are also essential to U.S. efforts. One method of achieving this might be a Western Pacific version of the Standing NATO Maritime Groups. An international squadron with rotating command responsibilities would be useful in easing old tensions and promoting better relations amongst this diverse group of nations.

The “long pole in the tent” of such a re-balancing strategy is how to manage the personnel disruptions such a change would cause. The CONUS-based U.S. deployment strategy, and dependent housing agreements in Japan and some Mediterranean nations has allowed for a great deal of family stability. Sailors can remain reasonably close to their families, even when forward deployed. There is no guarantee that Pacific or Mediterranean nations would accept large increases in the population of U.S. naval personnel and their dependents resident within their borders. In addition to the foreign relation concerns, such additions would cost a considerable amount of money and involve greater security risks in protecting a larger overseas American service and dependent population. The answer to this problem is to ‘dust off’ some of the reduced and creative manning projects of the last decade. While not ideal in many ways, reduced manning, crew swaps, and longer, unaccompanied deployments may become the norm, rather than the exception for American sailors.

Unfortunately, this is the price of putting more credible combat power in forward areas at present or even reduced costs. The U.S. will be hard-pressed to duplicate Admiral Fisher’s other revolutionary changes. The U.S. Navy has retired nearly all of its outdated warships, and further reductions of newer platforms will harm overall naval capabilities. Revolutionary changes in armament such as the rail gun and other directed energy weapons, and continued advances in the electric drive concept may allow for some cost reductions in naval expenditures, but they remain far from mature development. The rail gun is slated for additional afloat testing, but with a barrel life of only 400 rounds, it represents a 21st century equivalent of the arquebus.4 Fisher, by contrast, had relatively mature technological solutions in propulsion, and rushed fire control, aircraft, and submarine advances into full production with mixed results. The present U.S. test and evaluation culture would not permit such bold experimentation.

The U.S. can, however, improve its overall forward naval posture by re-balancing its force structure along geographic lines to better support national interests and regional commanders’ requirements. Additional force structure will be difficult to achieve in the face of present budget woes. Transformational technology is moving toward initial capabilities, but is not yet ready for immediate, cost savings application. The post-1948 CONUS-based deployment system is becoming more difficult to maintain with fewer ships and persistent commitments. Despite these dilemmas, the U.S. must fundamentally change the deployment and basing structure of the fleet in order to provide credible combat power forward in support of joint commander requirements. The new 2015 Maritime Strategy will not achieve many of its goals using the present CONUS-based deployment construct. Geographic re-balance of the fleet will provide strength were it is most needed.

1. A detailed explanation of the Fisher/Selborne re-balance strategy may be found in Aaron Friedberg’s The Weary Titan, Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905, pages 135-208.

2. Captain Jerry Hendrix, USN (ret), PhD, “At What Cost a Carrier”, Center for New American Security (CNAS), March 2013, p. 7.

3. Conversation with retired NSWCCD Senior Warfare Analyst James O’Brasky.

4. 15 February statement of Statement of Rear Admiral Mattew L. Klunder, USN, Chief Of Naval Research before the Intelligence, Emerging Threats and Capabilities Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee on the Fiscal Year 2015 Budget Request, 26 March, 2014.