This article was submitted by guest author Marjorie Greene for CIMSEC’s Distributed Lethality week. Ms. Greene is a Research Analyst with CNA. Views expressed are her own.

What will distributed lethality command and control look like? This article introduces a self-organizing approach that addresses this question. The increasing vulnerability of centralized command and control systems in network warfare suggests it may be time to take an entirely new approach that builds on the human capacity to interact locally and collectively with one another. Building on the concept of swarm intelligence, the approach suggests that information could be “shared” in a decentralized control system, much as insect colonies share information by constructing paths that represent the evolution of their collective knowledge.

This article builds on a self-organizing system that was developed for military analyses aimed at finding out “who talks to whom, about what, and how effectively” in a wide range of operational situations featuring the involvement of naval forces and commands. In an effort to describe the content of message traffic throughout the chain of command during a crisis, a technique was used to associate messages with each other through their formal references. “Reference-connected sets” were constructed that required no interpretation of the subject matter of the messages and, when further analyzed, were found to uniquely identify events during the crisis. For example, one set that was constructed from crisis-related message traffic found in files at three command headquarters contained 105 messages that dealt with preparation for landing airborne troops. Other sets of messages represented communications related to other events such as providing medical supplies and preparing evacuation lists. The technique therefore provided a “filter” of all messages during the crisis into events that could be analyzed – by computers or humans – without predetermined subject categories. It simply provided a way of quickly locating a message that had the information (as it was expressed in natural language) that was necessary to make a decision [1].

As the leaders of the Surface Navy continue to lay the intellectual groundwork for Distributed Lethality, this may be a good time to re-introduce the concept of creating “paths” to represent the “collective behavior” of decentralized self-organized systems” for control of hunter-killer surface action groups. Technologies could still be developed to centralize the control of multiple SAGs designed to counter adversaries in an A2/AD environment. But swarm intelligence techniques could also be used in which small surface combatants would each act locally on local information, with global control “emerging” from their collective dynamics. Such intelligence has been used in animal cultures to detect and respond to unanticipated environmental changes, including predator presence, resource challenges, and other adverse conditions without a centralized communication and control system. Perhaps a similar approach could be used for decentralized control of Distributed Lethality.

Swarm intelligence builds on behavioral models of animal cultures. For example, the ant routing algorithm tells us that when an ant forages for food, it lays pheromones on a trail from source to destination. When it arrives at its destination, it returns to its source following the same path it came from. If other ants have travelled along the same path, pheromone level is higher. Similarly, if other ants have not travelled along the path, the pheromone level is lower. If every ant tries to choose a trail that has higher pheromone concentration, eventually the pheromones accumulate when multiple ants use the same path and evaporate when no ant passes.

Just as an ant leaves a chemical trace of its movement along a path, an individual surface combatant could send messages to other surface ships that include traces of previous messages by means of “digital pheromones.” One way to do this would be through a simple rule that ensures that all surface ships are kept informed of all previous communications related to the same subject. This is a way to proactively create a reference-connected message set that relates to an event across all surface ships during an offense operation.

In his book, Cybernetics, Norbert Wiener discusses the ant routing algorithm and the concept of self-organizing systems. He does not explicitly define “self-organization” except to suggest it is a process which machines – and, by analogy, humans – learn by adapting to their environment. Now considered to be a fundamental characteristic of complex systems, self-organization refers to the emergence of higher-level properties and behaviors of a system that originate from the collective dynamics of that system’s components but are not found in nor are directly deducible from the lower-level properties of the system. Emergent properties are properties of the whole that are not possessed by any of the individual parts making up that whole. The parts act locally on local information and global order emerges without any need for external control.

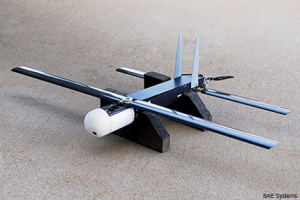

The Office of Naval Research has recently demonstrated a new era in autonomy and unmanned systems for naval operations that has great promise for Distributed Lethality. The LOCUST (Low-Cost UAV Swarming Technology) program utilizes information-sharing

between UAVs to enable autonomous collaborative behavior in either defensive or offensive scenarios. In the opinion of this author, this program should be analyzed for its potential application to Distributed Lethality.

Professor Vannevar Bush at MIT was perhaps the first person to come up with a new way of thinking about constructing paths for information-sharing. He suggested that an individual’s personal information storage and selection system could be based on direct connections between documents instead of the usual connections between index terms and documents. These direct connections were to be stored in the form of trails through the literature. Then at any future time the individual himself or one of his friends could retrieve this trail from document to document without the necessity of describing each document with a set of descriptors or tracing it down through a classification tree [2].

The current response to the dilemmas associated with command and control in any distributed operation has led this author to embrace the concept of swarm intelligence. Rather than attempting to interpret the subject matter of information exchanged by entities in confronting an adversary, why not build control systems that simply track information “flows”? Such flows would define the subject matter contained in a naval message without having to classify the information at all.

Any discussion of command and control would be incomplete without including the concept of fuzzy sets, introduced by Professor Lotfi Zadeh at the University of California, Berkeley in 1965. The concept addresses the vagueness that is inherent in most natural language and provides a basis for a qualitative approach to the analysis of command and control in Distributed Lethality. It is currently used in a wide range of domains in which information is incomplete or imprecise and has been extended into many, largely mathematical, constructions and theorems treating inexactness, ambiguity, and uncertainty. This approach to the study of information systems has gained a significant following and now includes major research areas such as pattern recognition, data mining, machine learning algorithms, and visualization, which all build on the theoretical foundations established in information systems theory [3].

Ultimately, the information paths constructed for the control of Distributed Lethality will be a function of organizational relationships and the distribution of information between them. Since a message in a path cannot reference a previous message unless its originator is cognizant of the previous message, the paths in a “reference-connected set” of messages will often reflect the information flows within a Surface Action Group. When paths are joined with other paths, the resulting path often reflects communications across Surface Action Groups. It remains to be determined whether the Surface Navy can use these concepts as it continues to explore the intellectual groundwork for Distributed Lethality. Nevertheless, it is very tempting to speculate that swarm intelligence will play an important role in the future. The most important consideration is that this approach concentrates on the evolution of an event, rather than upon a description of the event. Even if a satisfactory classification scheme could be found for control of hunter-killer Surface Action Groups, the dynamic nature of their operations suggests that predetermined categories would not suffice to describe the complex developments inherent in evolving and potentially changing situations.

Many organizations have supported research and development designed to explore the full benefits of shared information in an environment in which users will be linked through interconnected communications networks. However, in the view of this author, the model of “trails of messages” should be explored again. “Network warfare” will force an increased emphasis on human collaborative networks. Dynamic command and control will be based on communications paths and direct connections between human commanders of distributed surface ships rather than upon technologies that mechanically or electronically select information from a central store. Such an approach would not only prepare for Distributed Lethality, but may improve command and control altogether.

Ms. Greene is a Research Analyst with CNA. Views expressed are her own.

REFERENCES:

- Greene, , “A Reference-Connecting Technique for Automatic Information Classification and Retrieval”, OEG Research Contribution No. 77, Center for Naval Analyses, 1967

- Bush, V., “As We May Think”, Atlantic Monthly 176 (1):101-108, 1945

- Zadeh, L.,” Fuzzy sets”, Information Control 8, 338-353, 1965