Guest post for Chinese Military Strategy Week by Daniel M. Hartnett

A Comparison of U.S. and Chinese Views of the International Strategic Environment

Within approximately a month of each other this year, both China and the United States published official documents detailing their respective views of the current security environment. China’s assessment was captured in its 9th biennial defense white paper, published in late May, and officially titled China’s Military Strategy. The U.S. view is presented in the National Military Strategy of the United States of America, 2015 (hereafter, U.S. National Military Strategy), published in June. The authoritative nature of each document provides an interesting opportunity to comparatively assess how both nations see the international military and security situation, more clearly understand their similarities and differences, and draw out any relevant implications.

Before comparing the views contained within the two documents, however, it is important to clarify that this is not a perfect comparison. Although both documents are official and therefore represent the approved views of the respective government, they are not exact equivalents. China’s defense white paper, while drafted by the Chinese military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), is actually coordinated with and vetted by China’s foreign policy making community, to most importantly include the Chinese Communist Party.1 Therefore, it represents the view of the Chinese Party-State, not just the PLA. On the other side of the ledger, the Joint Chiefs of Staff is responsible for producing the U.S. National Military Strategy. This document draws closely from other U.S. government statements, most importantly from the President’s National Security Strategy. However, ultimately the U.S. National Military Strategy is a U.S. military document, not a whole-of-government product. As a result, comparing it with China’s Military Strategy is imperfect at best. However, such an exercise is still of value, particularly given the authoritativeness of the two documents combined with the general lack of publicly released official Chinese statements on national defense issues.

Going forward with this imperfect yet still useful comparison of these two views on the international security situation yields four findings of interest. First, both documents describe the international security situation as experiencing great change. According to the U.S. National Military Strategy, “complexity and rapid change characterize the strategic environment, driven by globalization, the diffusion of technology, and demographic shifts.” China’s defense white paper paints a similar picture, stating that “profound changes are taking place in the international situation.” Although China’s Military Strategy is silent on what is causing these changes, it does assert that the changes in question are changes to the international balance of power, global governance structure, and Asia-Pacific geostrategic landscape, as well as an increase in international economic, military, and technological competition.

Second, although they both maintain the international system is in flux, the two documents disagree about the impact these changes will have. The U.S. National Military Strategy takes a more pessimistic view, stating that these changes are giving rise to a host of problems. As General Martin Dempsey, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, writes in the foreword to the U.S. National Military Strategy, “today’s global security environment is the most unpredictable I have seen in 40 years of service,” and that “global disorder has significantly increased while [U.S.] comparative military advantage has begun to erode.” Concerns noted include increasing societal tensions, resource competition, political instability, military challenges, and non-traditional security concerns. More concerning, the document also asserts that the risk of “U.S. involvement in interstate war with a major power is assessed to be low but growing” [emphasis added].

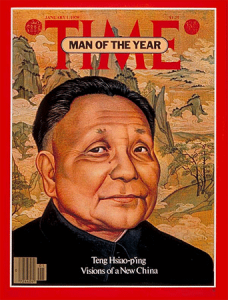

China’s assessment, on the other hand, is more positive. It asserts that overall the international situation is good, although it also recognizes that some problems exist. For example, the document maintains that “peace, development, cooperation and mutual benefit have become an irresistible tide of the times,” continuing a basic position held since the mid-1980s when then Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping took China off the constant pre-war footing of Mao Zedong.2 That doesn’t mean that China’s Military Strategy doesn’t recognize the existence of international problems; the document notes such issues as “hegemonism, power politics, and neo-interventionism,” as well as increasing competition for power and interests, international terrorism, and ethnic, religious, and territorial disputes. However, it does assert that “the forces for peace are on the rise, [and] so are the factors against war,” and as a result, a major war is unlikely and the “international situation is expected to remain generally peaceful”—although minor conflicts and wars can occur. More importantly, China’s Military Strategy states explicitly that China confronts a “generally favorable external environment,” something the document claims is a prerequisite for China’s continued development.

Third, the two documents focus on different levels of the international system. The U.S. National Military Strategy, for example, squarely assesses the international situation from a global perspective. For example, the four countries mentioned by name as revisionist (Russia, Iran, North Korea, and China) span much of the globe. Similarly, when discussing the threat of violent extremist organizations, the document notes this is a global concern (although it does highlight the Middle East and North Africa for exceptional concern). Furthermore, the U.S. National Military Strategy explicitly rejects the notion of emphasizing any one region or issue, stating that “the U.S. military does not have the luxury of focusing on one challenge to the exclusion of others.”

In contrast, China’s Military Strategy emphasizes China’s periphery, and in particular the maritime areas of the western Pacific Ocean. Although global issues are mentioned, they are done so only briefly and ambiguously. Instead, China’s Military Strategy mainly discusses regional concerns. Concerns noted include the U.S. rebalance to Asia, especially efforts to strengthen the U.S. military presence and alliances in the region; Japan’s ongoing adjustments to its defense policy; tensions on the Korean Peninsula; relations with Taiwan; and extremist movements that could spill over China’s borders. Of particular note is China’s focus on maritime concerns, such as the growing tensions concerning its disputed claims in the East and South China seas, U.S. special reconnaissance operations, and alleged outside interference in China’s maritime disputes. The only non-peripheral concern expressly noted in the document reflects the recognition that China’s growing overseas interests are creating new security issues, such as sea lane security and the security of Chinese foreign investments and overseas citizens.

Fourth, each document portrays the other country as part of the problem. According to China’s Military Strategy, the increase in China’s peripheral insecurity is partially due to U.S. actions in the region, such as the U.S. rebalance to Asia and its interference in China’s maritime disputes with other East Asia states. For its part, the U.S. National Military Strategy also explicitly calls out China, stating that its “aggressive land reclamation efforts” in the South China Sea could allow the PLA to position forces “astride vital international sea lanes.” As a result, “China’s actions are adding tension to the Asia-Pacific region.” This mutual finger pointing in order to assign blame for tensions in the South China Sea exemplifies what Dr. David M. Finkelstein, director of CNA’s China Studies division, has referred to as a “perception gap” between China and the United States on regional security concerns.

From this simple comparison of the two authoritative documents, it is easy to see that a large divide exists between the U.S. and Chinese views on security issues. While the United States sees the rapidly changing international systems as a potential concern, China sees it as an opportunity for continued development. The U.S. focus on the global level is indicative of its position as an established global power with global interests. Conversely, China’s focus, although gradually expanding to the international level, emphasizes the East Asia region, reflecting that Beijing continues to be primarily concerned with its immediate periphery. Each country also sees the other as part of the problem, especially in the case of the South China Sea issue.

Ultimately this difference in views should not be shocking since both countries have their own set of national interests and related concerns. The more important questions, however, are: Is it possible, as some claim, to bridge these differences and build “mutual trust” between the two militaries? Or will asymmetries of interest on certain issues prevent reaching a peaceful accord? Can the two militaries reach a middle ground on issues where they see the other as the main culprit? For this author, it would seem a difficult challenge, for as the Truman-era senior bureaucrat Rufus F. Miles said in the late 1940s, “Where you stand depends on where you sit.”3

Daniel Hartnett is a research scientist with CNA’s China Studies division, as well as a member of the Truman National Security Project’s Defense Council. He can be followed at @dmhartnett. The views expressed in this article are his alone.

[1] Daniel M. Hartnett, “China’s 2012 Defense White Paper: Panel Discussion Report,” CNA Conference Proceeding (September 2013), p. i.

[2] For an interesting read on China’s military reforms during the Deng era, see Ezra Vogel, Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of China (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), pp. 523-552.

[3] Rufus F. Miles, “The Origin and Meaning of Miles’ Law,” Public Administration Review Vol. 38, No. 5 (Sep. – Oct., 1978), pp. 399-403.