Sea Control discusses the Baltic perception – specifically Swedish – of the Russian threat with Aaron Korewa and Katarina Tracz. This is the first of several future podcasts with our friends from Sweden.

Sea Control discusses the Baltic perception – specifically Swedish – of the Russian threat with Aaron Korewa and Katarina Tracz. This is the first of several future podcasts with our friends from Sweden.

The Legal Rationale for Going Inside 12

The following post by Dr. James Kraska was originally published at the Asia Maritime Transparency Initiative. It is re-posted here with the author’s permission.

While China conducts innocent passage around real U.S. islands of Alaska, the U.S. is apparently unable to do so around China’s fake islands in the South China Sea. The transit by Chinese warships in innocent passage through the territorial sea of Attu Island in the Aleutian chain has added an additional wrinkle to U.S. policy in the South China Sea.

On May 12, the Wall Street Journal reported that Secretary of Defense Ash Carter had asked his staff to “look at options” for exercising the rights and freedom of navigation and overflight in the EEZ, to include flying maritime patrol aircraft over China’s new artificial islands in the region, and sending U.S. warships to within 12 nautical miles of them. Later that month, a P-8

surveillance aircraft with a CNN crew on board, was repeatedly warned to “go away quickly” from Fiery Cross Reef, even as it flew beyond 12 nm from the feature. Fiery Cross Reef is a Chinese-occupied outcropping that has been fortified by a massive 2.7 million square meter land reclamation into an artificial island with a 3,110-meter airstrip and harbor works capable of servicing large warships.

Warships and commercial vessels of all nations are entitled to conduct transit in innocent passage in the territorial sea of a rock or island of a coastal state, although aircraft do not enjoy such a right. Ironically, the website POLITICO reported on July 31 that the White House blocked plans by Admiral Harry Harris, Commander, U.S. Pacific Command, to send warships within 12 nm of China’s artificial islands – features that may not even qualify for a territorial sea. By blocking such transits, military officials apparently suggest that the White House tacitly accepts China’s unlawful claim to control shipping around its occupied features in the South China Sea. Senator John McCain complained that the United States was making a “dangerous mistake” by granting de facto recognition of China’s man-made “sovereignty” claims.

It is unclear whether features like Fiery Cross Reef are rocks or merely low-tide elevations that are submerged at high tide, and after China has so radically transformed them, it may now be impossible to determine their

natural state. Under the terms of the law of the sea, states with ownership over naturally formed rocks are entitled to claim a 12 nm territorial sea. On the other hand, low-tide elevations in the mid-ocean do not qualify for any maritime zone whatsoever. Likewise, artificial islands and installations also generate no maritime zones of sovereignty or sovereign rights in international law, although the owner of features may maintain a 500-meter vessel traffic management zone to ensure navigational safety.

Regardless of the natural geography of China’s occupied features in the South China Sea, China does not have clear legal title to them. Every feature occupied by China is challenged by another claimant state, often with clearer line of title from Spanish, British or French colonial rule. The nation, not the land, is sovereign, which is why there is no territorial sea around Antarctica – it is not under the sovereignty of any state, despite being a continent. As the United States has not recognized Chinese title to the features, it is not obligated to observe requirements of a theoretical territorial sea. Since the territorial sea is function of state sovereignty of each rock or island, and not a function of simple geography, if the United States does not recognize any state having title to the feature, then it is not obligated to observe a theoretical territorial sea and may treat the feature as terra nullius. Not only do U.S. warships have a right to transit within 12 nm of Chinese features, they are free to do so as an exercise of highs seas freedom under article 87 of the Law of the Sea Convention, rather than the more limited regime of innocent passage. Furthermore, whereas innocent passage does not permit overflight, high seas freedoms do, and U.S. naval aircraft lawfully may overfly such features.

In response, it might be suggested that while the United States may not recognize Chinese ownership of the rocks, it must realize that some country, perhaps one of the coastal states actually located in the vicinity of the feature, has lawful title, and therefore the U.S. Navy is bound to observe a putative territorial sea.

It is possible, however, that there is no state that has lawful title, and indeed the swirling debate and paucity of evidence rendered by claimants suggests this may be the case. Before World War II, few if any of the features were effectively governed by anyone, except Japan, which illegally occupied them during war. Tokyo gave up its claim after World War II. Similarly, actions taken by states after 1945 to seize maritime features using armed aggression are prima facie unlawful under article 2(4) of the Charter of the United Nations. Furthermore, actions taken by a state to fortify its claim after there is a dispute are similarly void of legal effect. In any event, the strongest claims appear to flow from the doctrine of uti possidetis, which stipulates that lawful possession is assumed by colonies after they become independent states. Prior to 1945, conquest was a lawful means of acquiring title to territory, so the European colonial powers certainly enjoyed legal title to the features they controlled. The Philippines, Malaysia and Brunei, Indonesia, and Vietnam derive their title to features from Spain, Great Britain, the Netherlands, and France.

More importantly, even assuming that one or another state may have lawful title to a feature, other states are not obligated to confer upon that nation the right to unilaterally adopt and enforce measures that interfere with navigation, until lawful title is resolved. Indeed, observing any nation’s rules pertaining to features under dispute legitimizes that country’s claim and takes sides. This point is particularly critical for commercial overflight since states already manage international air traffic through the International Civil Aviation Organization and the worldwide air traffic control regions. Finally, there is a policy reason that supports this approach. Given the proliferation of claims over the hundreds of rocks, reefs, skerries and cays in the South China Sea, if the international community recognizes the maximum theoretical rights generated by each of them, the oceans and airspace will come to look like Swiss cheese and be practically closed off to free navigation and overflight.

Distinguished American historian Samuel Flagg Bemis called the doctrine of freedom of the seas the “ancient birthright” of the American Republic.[1] This birthright faces its gravest risk since unrestricted submarine warfare. Woodrow Wilson brought the United States into World War I to vindicate a Fourteen Point program for peace. Point number 2 was for “freedom of navigation … in peace and in war.” Similarly, Franklin D. Roosevelt and Winston Churchill signed the Atlantic Charter in 1941 that set forth principles for a new world order – a united nations. Principle Seven committed them to freedom of the seas. Maritime freedoms and the law of the sea are at an inflection point. The United States and the international community must take action now to operate with regularity on, under, and above the surface of the South China Sea, persistently and routinely in the vicinity of China’s artificial islands. Only a normalized presence today will ensure predictability and stability tomorrow.

[1] Samuel Flagg Bemis, A Diplomatic History of the United States, 4th ed. (New York: Henry Holt, 1955): 875.

Dr. James Kraska is Professor in the Stockton Center for the Study of International Law, where he previously served as Howard S. Levie Chair in International Law from 2008-13. During 2013-14, he was a Mary Derrickson McCurdy Visiting Scholar at Duke University, where he taught international law of the sea. He is also a Senior Fellow at the Center for Oceans Law and Policy at the University of Virginia School of Law, Guest Investigator at the Marine Policy Center, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Senior Fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute, and a Senior Associate at the Naval War College’s Center on Irregular Warfare and Armed Groups.

The Hohenzollern Chinese Navy? Part Two

The High Seas Fleet and the PLAN: Striking Similarities in Strategy, Force Structure and Deployment

The first part of this series examined the nearly identical origins, and dismal, early combat histories. This second installment compares the equally similar strategy, operational art, and force structure, and concludes with observations on the PLAN can avoid the fate of the High Seas Fleet. Read Part One here.

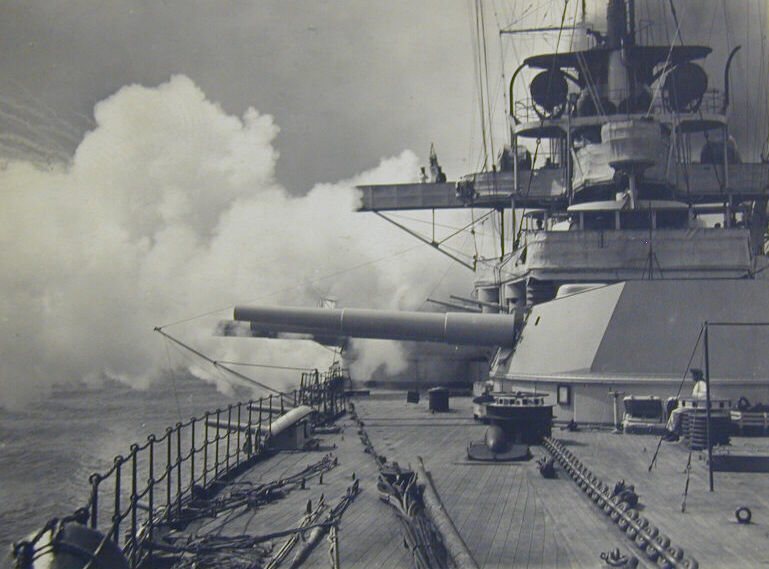

Both new fleets entered their identifiable “blue water” eras with similar strategies, operational concepts and tactics. The German High Seas Fleet retained robust coastal defense force structures even as its focus moved to the maritime space outside its own near abroad. This dual aspect of coastal and blue water operations was a key element in German strategy that was designed to defeat Great Britain’s Royal Navy (RN). High Seas Fleet architect Admiral von Tirpitz believed that a German Navy 2/3 the strength of the RN would be sufficient to defeat the British Navy in a battle if waged in German terms. Tirpitz envisioned drawing a portion of the RN into battle in the North Sea, but reasonably coast to German bases where torpedo craft (surface and subsurface), minefields and even shore batteries on advanced locations such as Heligoland Island might support the High Seas Fleet. German naval historian Holger Herwig suspects that Tirpitz never intended to attack Britain, but hoped that “British recognition of the danger posed by the German Fleet concentrated in the North Sea”, would “Allow the Emperor to conduct a greater overseas policy.”[1] The possibility would always exist that if Great Britain still defeated the German Navy in battle that it would be too damaged and perhaps, “Find itself at the mercy of a third strong naval power or a coalition (France and Russia).[2] Herwig also suggests that other would-be maritime powers might be inspired by Germany’s example and perhaps convince those nations to seek Germany as an ally. To achieve these ends, Tirpitz in effect attempted to create the early 1900’s equivalent of an Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) zone in the Heligoland Bight of the North Sea.

Evidence suggests that the PLAN is following a similar strategy. The Chinese are well on their way to building a very credible, regional naval capability.[3] The PLAN’s emphasis on operations within the Chinese defined “first island chain” seems to mirror Tirpitz’s focus on decisive battle in the North Sea. There is no evidence to suggest the Chinese are planning to launch an aggressive naval war against the United States, but are building naval forces sufficient to convince the United States and other would be opponents that the risk involved in combating such a force will entail significant naval losses. As Germany acquired the island of Heligoland in 1890 in order to secure the naval approaches to its significant ports from blockade, China is seeking to control and expand islets in the South China Sea in order to create a buffer zone around its sea lines of communication with its primary hydrocarbons supply sources in the Persian Gulf. Control of the South China Sea would also support potential military operations to place Taiwan under Communist Chinese control. Tirpitz thought his fleet would prevent Britain from considering a preemptive attack on Germany, as it had done on a nascent Danish Navy at Copenhagen in 1805. China appears to be creating its own A2/AD network to similarly deter U.S. action against the People’s Republic in the event of conflict over Taiwan, or contested islands in the South and East China Seas. Like Great Britain a century ago, the U.S. today must consider, “whether the U.S. Navy in coming years will be large and capable enough to adequately counter improved Chinese maritime forces while also adequately performing other missions around the world.”[4]

Although it is clearly building a “blue water” fleet that includes aircraft carriers, capable surface ships and submarines, the PLAN also maintains large forces of missile-armed littoral combatants analogous to the large German light forces of the early 20th century. China also has a much more powerful equivalent to the German shore batteries in the form of the Anti-ship Ballistic Missile, but this weapon does not yet appear to have been successfully tested against a moving target at sea.[5] With the bulk of its blue water fleet concentrated in home waters, and supported by similarly-based aircraft, submarines, land-based missiles and light naval forces, China has deployed a naval force structure remarkably similar to that of Imperial Germany. It appears focused on the control of its immediate sea zone and intended to deter the maritime hegemon from interference in its growing global economic, political and possible military activity.

There are some trends to suggest some of the new blue water PLAN units will deploy beyond the first island chain and operate in regular deployments abroad as the U.S. Navy has done since 1948.[6] Such deployments are fraught with peril if unsupported by a large global naval support structure and close allies. Admiral Graf von Spee’s crack cruiser squadron was deployed overseas at the German Pacific colony of Tsingtao (now the Chinese city and naval base of Qingdao) in 1914, but Tirpitz otherwise kept the heavy units of the High Seas fleet almost entirely in home waters for deterrence and potential combat against the Royal Navy. A future Chinese von Spee might wreak havoc on shipping and naval forces in the Indian Ocean or Red Sea, but would also be, “a cut flower in a vase, fair to see, yet bound to die” as Churchill said of the German commander.[7]

A Similar Potential for Catastrophic Failure

Both navies also share similar traits that eventually led to catastrophic failure in war for the High Seas Fleet. Admiral von Tirpitz based his strategy for victory against the Royal Navy on superior technology and highly trained personnel as well as specific numbers of capital ships. German warships were slower, had smaller guns and more austere in accommodation than their British counterparts, but had better gunnery optics, had thicker armor, and would prove more survivable in combat thanks to superior internal subdivision. German naval personnel were also expected to be more technically expert and better disciplined than their RN equivalents. This entailed adopting some of the harsher attributes of the Prussian Army to the naval service rather than forging a unique German naval culture to compete with that of the RN, who was the “motherhouse” for a multitude of world navies including those of the United States and Imperial Japan. Looking back in 1929, Germany’s official naval historian Admiral Eberhard von Mantley described the German naval culture of the Hohenzollern period as, “A Prussian Army Corps transplanted on to iron barracks.”[8]

The PLAN is likewise inured with the culture of a non-naval organization. The Communist Party of China plays a role in the Chinese navy similar to that played by the Imperial hierarchy in Hohenzollern Germany. The political work within the Chinese navy was once described as the “lifeline” of the service and essential to its support from the Chinese Communist Party.[9] The current commander of the PLAN, Admiral Wu Shengli, has long had close ties to the Communist Party through his father who was a Red Army political officer and governor of Zhejiang. Admiral Wu may also have had close ties to future Chinese President Jiang Zemin, who served as Shanghi Party Secretary when Wu was Deputy Chief of Staff for the Shanghai naval Base in the 1970’s and 1980’s. Like the support from the Chinese Communist Party, the Kaiser’s patronage, support and favor toward the Hohenzollern German Navy was that force’s connection to the German ruling elite and they budgetary support that connection supported.

Naval historian Norman Friedman has suggested that one of the great flaws of the Hohenzollern fleet is that it was built without a clear strategic objective in Germany’s overall national military strategy.[10] Admiral von Tirpitz was very effective in assembling political and public support for a large fleet of capital ships, but when war did occur he did not have a defined plan as to how this very expensive fleet would be used. Friedman also points out that the German General Staff also no idea of what to do with the High Seas Fleet and that neither naval nor military leadership ever exploited its potential until late in the war with the U-boat campaign, which did not involve Tirpitz’ heavy surface units. German naval officers, especially those of senior rank also had little or no combat experience in 1914 against which to measure their operational performance at the outset of war.

While the Chinese have long planned on using naval forces to support the potential reclamation of Taiwan, and to protect vulnerable littoral areas bordering the Chinese state, their construction of larger warships such as carriers and large surface combatants has wider and more uncertain strategic ends. The PLAN and Chinese Army/Air Force elements can certainly dominate the South China Sea and its immediate surroundings in the event of a major Pacific War for a significant period of time. Would it be possible, however, for the PLAN alone to venture further afield to break likely distant blockades of Chinese hydrocarbon supplies and trade with a core fleet of “two aircraft carriers, 20-22 AEGIS like destroyers and 6-7 nuclear attack submarines?”[11] Like Tirpitz fleet of a century ago, an enlarged PLAN is strong enough in its own backyard, but risks considerable losses if it ventures away from bases and meets the combined strength of US and allied joint forces. This “prestige” element of the PLAN, like the High Seas Fleet, may be equally lacking in full strategic assessment as was its German counterpart. In addition, senior PLAN officers, like their High Seas Fleet counterparts from 1914, lack combat experience in war at sea.

Dr. Friedman suggest one other potentially chilling possibility when he references German historian Volker Berghahn’s claim that the German General Staff and aristocratic establishment may have seen war as a means of preventing the rise of a Center left Reichstag as a political check against traditional Prussian authority.[12] A war was seen by military and Prussian establishment leaders as a means of rallying the increasing working class around national objectives and recreating the unifying environment that produced the German Empire at the conclusion of the Franco-Prussian War.

China’s stagnating economy, which slowed to 7.4% in 2014, a low figure not seen in 25 years, and the results of that change on the average Chinese citizen, has the potential to cause similar global unrest.[13] The Communist Chinese essentially made a bargain with Chinese citizens in the wake of the 1989 Tiananmen Square riots. It would “deliver stability and prosperity” in return for continued loyalty and support of the Communist Party. The party has kept that promise for the last quarter century and delivered a 20 fold increase in the average income.[14] With this economic tide now cresting and perhaps beginning to recede, might Communist leaders seek to rally the Chinese public to international and security issues in order to distract from a looming economic downturn and maintain its control over the Chinese state? It is interesting to note that belligerent Chinese rhetoric on its South and East China Seas claims, and associated land reclamation efforts accelerated as economic advances waned. Could Communist leaders resort to more aggressive international efforts in order to preserve their rule as some historians have suggested Hohenzollern Germany did in 1914?

U.S. writer Mark Twain is reputed to have said, “History dos not repeat itself, but it sometimes rhymes.” The development of the PLAN over the course of the Cold War and especially the last twenty five years seems to rhyme very closely with that of the Hohenzollern High Seas Fleet. There are, however, some comforting differences. China is not nominally ruled by a mercurial Kaiser and has no Admiral von Tirptiz that is fully disconnected from other state organs of national security planning. It is not likely planning actual war with the United States or its close Pacific allies. That said, whether in mitigation of internal economic issues or paranoia over its seaborne hydrocarbon supply routes, China has engaged in a direct challenge to U.S. maritime superiority not seen since the Soviet Union created a global navy in the early 1970’s. While the Soviet effort was in the context of a wider Cold War, the Chinese maritime buildup has taken place in what has been a zone of relative peace since the end of the 1970’s.

No nation, or group of nations has denied China’s rise to the very top of world economic indicators, or its right to build whatever military establishment it desires. The crux of the problem is China’s aggressive bid to use elements of maritime power to close off sections of heretofore international waters. It is similar to the Communist state’s past land-based activities such as seizing Tibet and engaging in punitive expeditions against Vietnam. Like Hohenzollern Germany, another land-based power looking to move seaward, China fails to comprehend the dangers in aggression directed toward powers dependent on the free flow maritime trade. China would be well served to turn its naval expansion program toward less provocative ends.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.

[1] Holger Herwig. The Luxury Fleet, The Imperial German Navy, 1888-1918, Abington/Oxon, UK and New York, Routledge Library Editions (reprint), The First World War, 2014, p. 36.

[2] Ibid.

[3] http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/will-china-have-a-mini-us-navy-by-2020/

[4] Ronald O’Rourke. China Naval Modernization: Implications for U.S. Navy Capabilities—Background and Issues for Congress”, Congressional Research Service, Washington D.C., 01 June 2015, p. ii.

[5] Ibid, p. 6.

[6] http://inss.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-9.pdf, p. 3.

[7] Winston S. Churchill, The World Crisis, 1911-1918, New York, Free Press/Simon and Schuster, 2005 edition, p. 177.

[8] Herwig, p.120.

[9] http://www.idsa-india.org/an-jan00-7.html

[10] Norman Freidman, Fighting the Great War at Sea, Strategy, Tactics and Technology, Annapolis, Md, Naval Institute Press, 2014, p. 22.

[11] http://thediplomat.com/2015/07/will-china-have-a-mini-us-navy-by-2020/

[12] Friedman, p. 21.

[13] http://www.wsj.com/articles/china-gdp-growth-is-slowest-in-24-years-1421719453

[14] http://www.institutionalinvestor.com/blogarticle/3347789/blog/a-generation-after-tiananmen-china-blends-amnesia-and-assertiveness.html#.Vbrq9PbbLIU

The Hohenzollern Chinese Navy? Part One

Recent Chinese pronouncements regarding the shift of their Navy from defensive to potential offensive operations contain a refrain with which naval historians are most familiar. It is a song once sung by another continental military power newly flush with a successful and expanding international economy.

China’s shift toward an offensive naval capability sounds very similar to the formation of the Imperial German High Seas Fleet (Hochseeflotte) in 1907. The Chinese and Hohenzollern navies have many commonalities in origin, training and choice of force structure. Their strategy, operational art and tactics are also remarkably similar to Kaiser Wilhelm’s fleet of the late 19th and early 20th century. The Chinese Navy may have also replicated the fatal flaw that left the High Seas Fleet incapable of achieving the victory it came so close to achieving in late 1917. Like the German imperial elite of the late 19th century, the Chinese Communist Party is now also seeking “a place in the sun” through President Hu Jinatao’s “new historic missions” assignment of 2004. China may too think that “its future is on the water” as did the Kaiser’s navy over a century ago. Such visions, however, for a fleet that has not seen battle against a peer opponent since 1894, can be dangerous.

Similar National Origins and Early Dismal Performance

Like Imperial Germany, the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is a continental land power that must look far into its past to find naval virtue. The Kaiser had to search back to the fifteenth century Hanseatic League in order to find heroic German maritime exploits that might be emulated by his own 20th century sailors. The PRC must equally rely on the historically remote Islamic Admiral Zheng He, who served the Ming Dynasty Yongle Emperor in the early 15th century as both a land and ocean-going commander. Both fleets were traditionally led by army officers and designed for coastal or at best littoral operations.

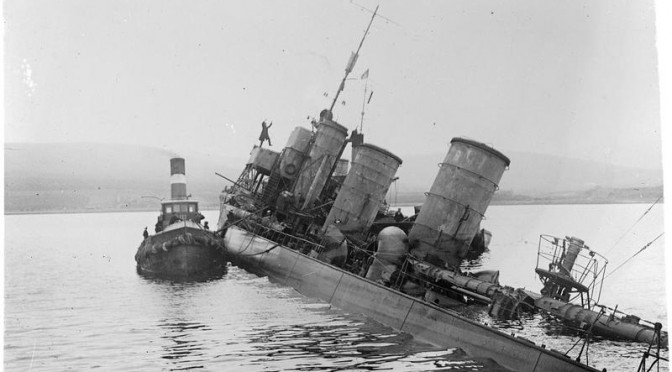

Both the German and Chinese fleets suffered from timid national leadership, and a paucity of training and operations that led to enforced idleness or defeat as late as the 19th century. Other Baltic powers often made short work of the Prussian Navy in war. The Swedes completely annihilated a Prussian fleet at the Battle of Frisches Haff in 1759. The Prussian Navy played practically no role in the three 19th century conflicts precipitated by Chancellor Otto von Bismarck that led to German unification. Its Danish, Austrian and French opponents either ignored, blockaded, or chased the small Prussian Navy from the seas. The Imperial Chinese Navy also suffered from neglect and poor performance from the Early Modern Period into the 20th century. The forces of the East India Company and the British Empire made short work of primitive Chinese warships in the two Opium wars of the mid 19th century. The French Navy destroyed the Chinese Fujian Fleet at the Battle of Fuzhou in 1884 and the Imperial Japanese Navy decisively defeated the Chinese Beiyang Fleet at the Battle of the Yalu River in 1894. The post-1949 People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has fought minor skirmishes against the Vietnamese, but has yet to engage anything approaching a regional, nor peer opponent in naval combat.

The German High Seas Fleet and the PLAN both had to be “reborn” in new political and economic environments of their respective nations. The united German state surged to new economic power between 1871 and 1906 and surpassed the British in steel production halfway into the first decade of the 20th century.[1] Germany also came close to equally British world trade and coal production by 1914.[2] Great Britain continued to prosper as both Germany and the United States surpassed Britain in key economic indicators and Britain’s Gross National Product grew from 1.32 billion to 2.1 billion Pounds over the period from 1870-1900.[3] Despite these changes, the British Empire did not regard either Germany of the U.S. as a potential enemy, and Canada’s shared border with the U.S. caused more concern to the British in 1900 than did Germany’s economic growth.[4] Germany, however, despite its unchallenged economic success decided to engage the British Empire in a naval building race that the British did nothing to instigate. Some historians have said the British detainment of several German ships transporting relief supplies to Dutch Boers during the Second Boer War (1899-1902), served as a catalyst for the passage of the German Second Naval Law which was much more provocative and aimed at Great Britain than its predecessor.[5] Emboldened by economic success and military strength, and baited into action by its inability to influence sea lines of communication outside its sphere of influence, Germany embarked on a risky warship building competition with the established naval hegemon at the time and made that challenge right on that naval power’s home doorstep.

China has had an equally meteoric economic rise since the time it also changed political organization by throwing off its Maoist past and embracing state-sponsored capitalism. Like Imperial Germany, post Mao China has combined pride in economic growth with its aggressive continental past. The People’s Republic appears to have had the same sort of decisive “maritime moment” as Imperial Germany when the U.S. deployed two aircraft carriers to the Taiwan Strait in 1996 as a response to simmering tensions between the PRC and Taiwan. There appears to have been a similar rage amongst the Chinese Communist Party and military leadership over the 1996 US deployment, as there was from German Aristocrats, businessmen and military leaders over the seizure of German relief ships off South Africa in 1900. It is this kind of significant public support that allowed for the growth in the German Navy of the early 20th century and may play a role in public support for an expanded PLAN.

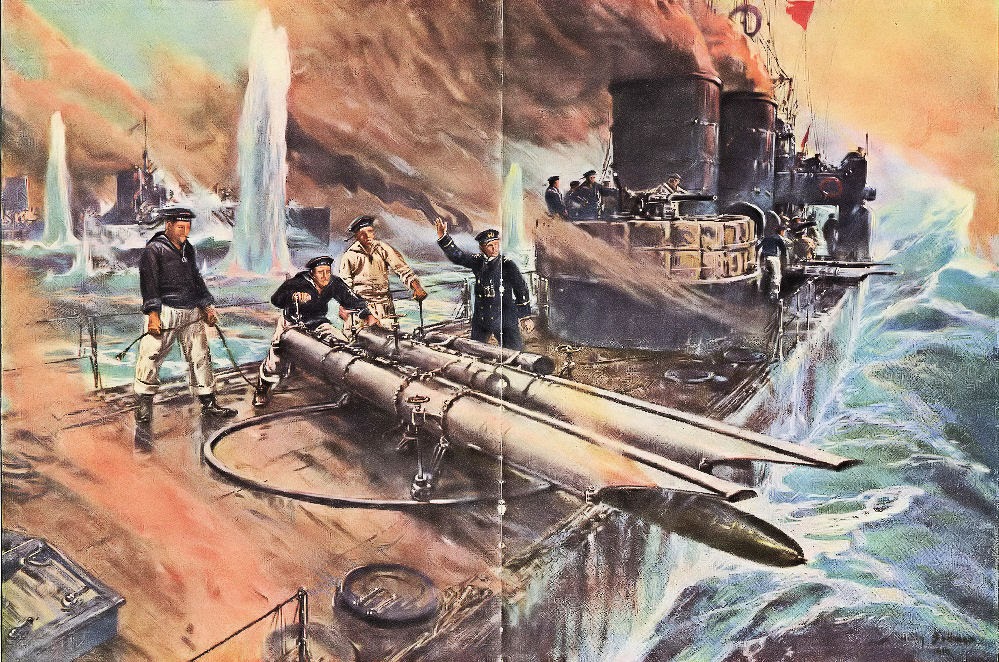

Both fleets also began as coast defense organizations led by Army officers and dependent on inexpensive denial capabilities. The early German Imperial Navy was first led by infantry General Albrecht von Stosch and General (and later Imperial Chancellor) Leo von Caprivi. It had few large ships and invested much of its effort in the development of torpedo craft and mine warfare. The architect of the High Seas battlefleet, Admiral von Tirpitz, and many of the Imperial Navy’s future senior officers came out of the German Navy’s torpedo boat arm. While Kaiser Wilhelm II played a very public advocacy role for larger and more capable surface ships, such expansion would not have been possible in the absence of strong support from the German business and political community. While perhaps not fervent navalists like the Kaiser, they certainly thought that having a Navy to protect emerging commercial interests was a good investment, and were willing to invest in Germany’s new naval effort. The spirit of American navalist Alfred Thayer Mahan’s writings on the importance of a battle fleet to a nation’s political and global economic health found as many adherents in Germany as it did in Great Britain, the United States, and Japan.

The early PLAN was also led by Army Generals. The most prominent advocate of improving Chinese naval capabilities was General Liu Huaqing, who served as PLAN commander from 1982-1987.[6] China’s naval strategy from 1949 through the 1980’s was also remarkably similar to Germany’s in that it was focused on coastal defense and emphasized missiles, torpedoes and mines deployed from small, coastal combatants. China appears to have also embraced the theories of Alfred Thayer Mahan as Germany did a century ago and added the study of the American navalist’s works to the curriculum of its advanced naval education courses.[7]

Part two of this article will examine how Hohenzollern Germany and the People’s Republic of China developed striking similarities in force structure, naval strategy, and deployment of their naval forces.

Read Part Two here.

Steve Wills is a retired surface warfare officer and a PhD candidate in military history at Ohio University. His focus areas are modern U.S. naval and military reorganization efforts and British naval strategy and policy from 1889-1941.

[1] Aaron Friedberg, The Weary Titan; Britain and the Experience of Relative Decline, 1895-1905, Princeton, NJ, Princeton University Press, 1988, p. 25.

[2] Ibid, pp. 24-25.

[3] Ibid, p. 24.

[4] Ibid, pp 185-186.

[5] Keith Wilson, editor, The International Impact of the Boer War, Abingdon Oxon, UK, Routledge, 2014, pp. 36-38.

[6] https://cimsec.org/father-modern-chinese-navy-liu-huaqing/13291, last assessed 16 June 2015.

[7] Howard J. Dooley, “The Great Leap Outward: China’s Maritime Renaissance”, The Journal of East Asian Affairs, 01 March 2012, p. 69.