The following article is part of our cross-posting partnership with Information Dissemination’s Jon Solomon. It is republished here with the author’s permission. Read it in its original form here.

Read part one, part two, and part three of this series.

By Jon Solomon

Ingredients of Counter-Deception

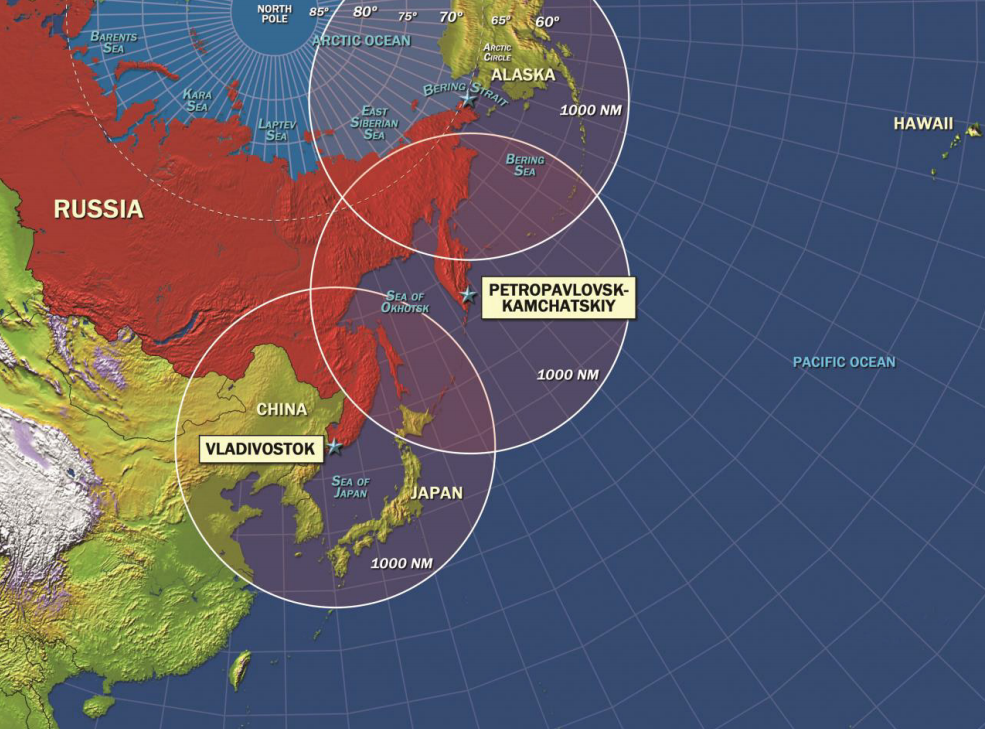

How could a U.S. Navy battle force then—or now—avoid defeats at the hands of a highly capable adversary’s deceptions? The first necessary ingredient is distributing multi-phenomenology sensors in a defense’s outer layers. Continuing with the battleforce air defense example, many F-14s were equipped during the 1980s with the AN/AXX-1 Television Camera System (TCS), which enabled daytime visual classification of air contacts from a distance. The Navy’s F-14D inventory later received the AN/AAS-42 Infrared Search and Track system to provide a nighttime standoff-range classification capability that complemented AN/AXX-1. Cued by an AEW aircraft or an Aegis surface combatant, F-14s equipped with these sensors could silently examine bomber-sized radar contacts from 40-60 miles away as meteorologically possible. As it would be virtually impossible for a targeted aircraft to know it was being remotely observed unless it was supported by AEW of its own, and as the targeted aircraft’s only means for visually obscuring itself was to take advantage of weather phenomena as available, F-14s used in this outer layer visual identification role could help determine whether inbound radar contacts were decoys or actual aircraft. If the latter, the sensors could also help the F-14 crews determine whether the foe was carrying ordnance on external hardpoints. This information could then be used by a carrier group’s Air Warfare Commander to decide where and how to employ available CAP resources.

It follows that future U.S. Navy outer layer air defenses would benefit greatly from having aircraft equipped with these kinds of sensors distributed to cover likely threat axes at extended ranges from a battle force’s warships. Such aircraft could report their findings to their tactical controllers using highly-directional line-of-sight communications pathways in order to prevent disclosure of the battle force’s location and disposition. Given that the future air threat will not only include maritime bombers but also strike fighters and small unmanned aircraft, it would be enormously useful if each manned aircraft performing the outer layer visual identification role could also control multiple unmanned aircraft in order to extend their collective sensing reach as well as covered volume. This way, the outer layer would be able to investigate widely-dispersed aircraft approaching on multiple axes well before the latter’s sensors and weapons could be employed against the battle force. The same physics that would allow the U.S. Navy to disrupt or exploit an adversary’s multi-phenomenology maritime surveillance and reconnaissance sensors could be wielded by the adversary against a U.S. Navy battleforce’s outer layer sensors, however, so the side that found a way to scout effectively first would likely be the one to attack effectively first.

A purely sensor-centric solution, though, is not enough. Recall Tokarev’s comment about making actual attack groups seem to be “easily recognizable decoys.” This could be implemented in many ways, one of which might be to launch readily-discriminated decoys towards a defended battle force from one axis while vectoring a demonstration group to approach from another axis. Upon identifying the decoys, a defender might orient the bulk of his available fighters to confront the demonstration group. This would be a fatal mistake, though, if the main attack group was actually approaching on the first axis from some distance behind the decoys. If there was enough spatial and temporal separation between the two axes, and if fighter resources were firmly committed towards the demonstration group at the time it became apparent that the actual attack would come from the first axis, it might not be possible for the fighters to do much about it. An attacker might alternatively use advanced EW technologies to make the main attack group appear to be decoys, especially when meteorological conditions prevented the CAP’s effective use of electro-optical or infrared sensors.

This leads to the second necessary ingredient: conditioning crews psychologically and tactically for the possibility of deception. During peacetime, tactical competence is often viewed as a ‘checklist’ skill set in that crews are expected to quickly execute various immediate actions by rote when they encounter certain tactical stimuli. There’s something to be said for standardized immediate actions, as some simply must be performed instinctively if a unit or group is to avoid taking a hit. Examples of this include setting General Quarters, adjusting a combat system’s configuration and authorized automaticity, launching alert aircraft, making quick situation reports to other units or higher command echelons, and employing evasive maneuvers or certain EW countermeasures. Yet, some discretion may be necessary lest a unit salvo too many defensive missiles against decoys or be enticed to prematurely reveal its location to an attacker. The line separating a fatal delay to act from a delayed yet effective action varies from circumstance to circumstance. A human’s ability to avoid the former is an art built upon his or her deep foundational understanding of naval science and the conditioning effects of regular, intense training. Only through routine exposure to the chaos of combat through training, and only when that training includes the simulated adversary’s use of deception, can crews gradually mentally harden themselves against the disorienting ambiguity or shock that would result from an actual adversary’s use of deception. Likewise, only from experience gained through realistic training can these crews develop tactics that help them and other friendly forces reduce their likelihoods of succumbing to deception, or otherwise increase the possibilities that even if they initially are deceived they can quickly mitigate the effects.

It follows that our third ingredient is possessing deep defensive ordnance inventories. A battle force needs to have enough ordnance available—and properly positioned—so that it can fall for a deception and still have some chance at recovering. It is important to point out this ordnance does not just include guns and missiles, but also EW systems and techniques. During the Cold War, a battle force’s defensive reserves consisted of alert fighters waiting on carrier decks to augment the CAP as well as surface combatants’ own interceptor missiles and EW systems. These might be augmented in the future by high-energy lasers used as warship point defense weapon systems, though it is too early to say whether their main ‘kill’ mechanism would be causing an inbound threat’s structural failure or neutralizing its terminal homing sensors. If effective, lasers would be particularly useful for defense against unmanned aircraft swarms or perhaps anti-ship missile types that trade away advanced capabilities for sheer numbers. Regardless of its available defensive ordnance reserves, a battle force’s ability to receive defensive support from other battle forces or even land-based Joint or Combined forces can also be quite helpful.

The final ingredients for countering an adversary’s deception efforts are embracing tactical flexibility and seizing the tactical initiative. Using Tokarev’s observations as an example, this can be as simple as constantly changing CAP and AEW cycle duration, refueling periods, station positions, and tactical behaviors. A would-be deceiver needs to understand his target’s doctrine and tactics in order to create a ‘story’ that meshes with the latter’s predispositions while exploiting available vulnerabilities. By increasing the prospective deceiver’s uncertainty regarding what kinds of story elements are necessary to achieve the desired effects, or where vulnerabilities lie that are likely to be available at the time of the planned tactical action, it becomes less likely that a deception attempt will be ‘complete’ enough to work as intended. A more aggressive defensive measure might be to use offensive counter-air sweeps well ahead of a battle force to locate and neutralize the adversary’s scouts and inbound raiders, much as what was envisioned by the U.S. Navy’s 1980s Outer Air Battle concept. The method offering the greatest potential payoff, and not coincidentally the hardest to orchestrate, would be to entice the adversary to waste precious ordnance against a decoy group or expose his raiders to ambush by friendly fighters. All of these concepts force the adversary to react, with the latter two stealing the tactical initiative—and the first effective blow in a battle—from the adversary.

In the series finale, we will address some concluding thoughts.

Read the series finale here.

Jon Solomon is a Senior Systems and Technology Analyst at Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. in Alexandria, VA. He can be reached at [email protected]. The views expressed herein are solely those of the author and are presented in his personal capacity on his own initiative. They do not reflect the official positions of Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. and to the author’s knowledge do not reflect the policies or positions of the U.S. Department of Defense, any U.S. armed service, or any other U.S. Government agency. These views have not been coordinated with, and are not offered in the interest of, Systems Planning and Analysis, Inc. or any of its customers.