The Southern Tide

The following article is the first in CIMSEC’s newest column: The Southern Tide. Written by W. Alejandro Sanchez, The Southern Tide will address maritime security issues throughout Latin America and the Caribbean. It will discuss the challenges regional navies face including limited defense budgets, inter-state tensions, and transnational crimes. It will examine how these challenges influence current and future defense strategies, platform acquisitions, and relations with global powers.

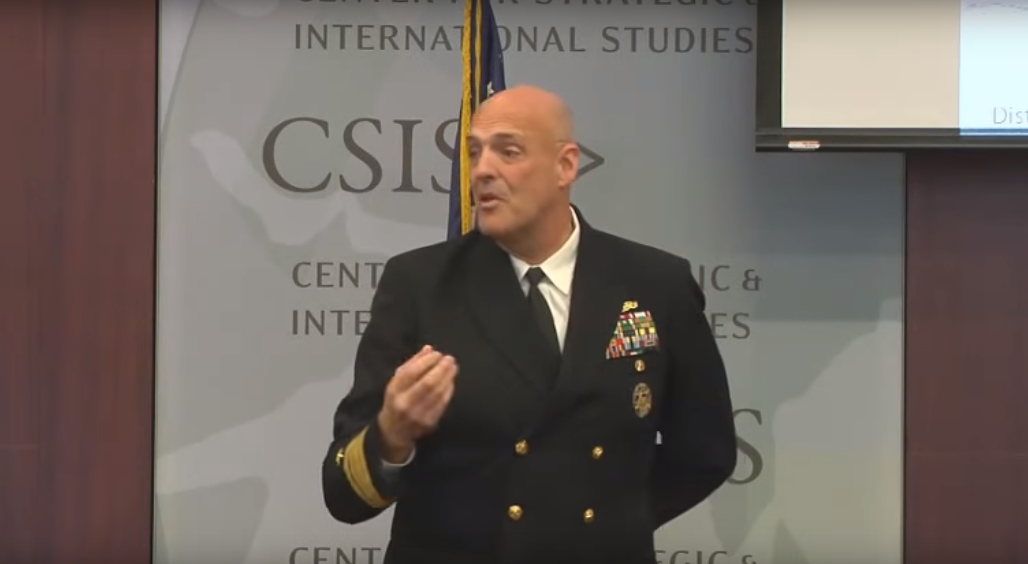

“The security environment in Latin America and the Caribbean is characterized by complex, diverse, and non-traditional challenges to U.S. interests.” Admiral Kurt W. Tidd, Commander, U.S. Southern Command, before the 114th Congress Senate Armed Services Committee, 10 March 2016.

By W. Alejandro Sanchez

Introduction

In mid-March, Argentina’s Coast Guard shot at and sank a Chinese vessel that was illegally fishing in its Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). Across the globe, navies and coast guards are devoting more resources to combat illegal fishing, as this maritime crime is a major cause of the depredation of the global maritime ecosystem. Latin America is no exception to this phenomenon, with the March incident in the South Atlantic exemplifying a worst case scenario. This focus towards combating maritime crimes, like drug trafficking and illegal fishing, has prompted a shift in strategies, and by extension, acquisitions among Latin American navies.

Illegal Fishing

Some examples are necessary in order to contextualize the amount of illegal fishing that is occurring in Latin American waters. It is important to mention that the following incidents occurred within the past seven months, which stresses the current gravity of this problem.

Unsurprisingly, there is a significant amount of illegal fishing carried out by fishermen within their own country’s territorial waters. For example, in May a vessel was accused of fishing close to the Revillagigedo archipelago, a Mexican biosphere off Baja California. Officers from Mexico’s Secretariat of the Navy escorted the vessel to port to investigate the origins of its multiple-ton load.

Fishermen often travel to another country’s sea without regard to international maritime borders. For example, in mid-April the Chilean Navy stopped a Peruvian vessel 74km off the coast of Antofagasta (northern Chile). The vessel had over two tons of shark meat that it had illegally fished in Chile’s EEZ. As for Colombia, in mid-February, the Navy stopped a Nicaraguan vessel that was lobster fishing in a protected area in the San Andres archipelago in the Caribbean. Months later, in early May, the Colombian Oceanic Patrol Vessel (OPV) ARC 20 de Julio stopped a vessel flying the Jamaican flag also off San Andres. The vessel was carrying one ton of different types of fish, including the parrotfish, which is protected under Colombian law.

Similarly, the Peruvian Navy seized 26 ships between January and March of this year alone off the country’s northern regions (Tumbes and Piura), which were engaged in illegal activities. While most of these vessels were fishing without authorization, five of these vessels were Ecuadorean pirates that attacked Peruvian fishing vessels in order to steal their cargo. This highlights the link between fishing and piracy in Latin America (while this problem may not be comparable to piracy off the Horn of Africa, it is a security threat nonetheless).

Nowadays, it is unsurprising to find Chinese fishing fleets sailing across Latin American waters, either on the Pacific or Atlantic side of the continent. In July 2015, Chile deployed its OPV Piloto Pardo and a Dauphin-type helicopter to stop a fleet of Chinese fishing vessels inside Chile’s EEZ. On that occasion, the Chilean Navy determined that the ships were not carrying out illegal fishing.

As for the March 2016 incident, three Chinese vessels were fishing without authorization in the South Atlantic, within Argentina’s EEZ. The Argentine Coast Guard utilized helicopters and vessels to chase the vessels as they ignored warnings to stop. Two ships managed to flee but the Argentines shot one boat, called the Lu Yan Yuan Yu 010. To make matters worse, Buenos Aires argues that while the vessel sank, it tried to ram an Argentine ship. Ultimately, the crew jumped into the sea and several were rescued and arrested by Argentine Coast Guard while others were picked up by the remaining Chinese ships.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jCvnjYupeWA

Argentine Coast Guard encounters Chinese fishing vessels. (CNN)

Enter the FAO

It is important to highlight that Latin American governments are approaching multinational organizations for support against illegal fishing. Case in point, in recent months numerous nations have signed agreements with the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations to unite against this crime. In fact, eight Latin American and Caribbean states (Barbados, Chile, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Guyana, St. Kitts and Nevis and Uruguay) have signed the legally binding Port State Measures Agreement (PSMA). It entered into force this past 5 June as the threshold for its activation was 25 countries and the PSMA now has 29 signatories (plus the European Union). This agreement is groundbreaking as it is regarded as the first international treaty that will directly address illegal fishing.

Moreover, in June, the Aquatic Resources Authority of Panama signed a separate agreement with the FAO to achieve “better sustainable management of fishery resources in the country safeguarding livelihoods, food production for local communities and marine ecosystems.” The FAO will now provide “technical assistance” to Panama City so the aforementioned Central American agency can formulate a national strategy to combat this crime.

The issue to keep in mind here is the greater attention that regional governments are giving illegal fishing, including requesting FAO support and pledges to fight this crime. This will have obvious repercussions in regional naval strategies and the acquisition of sea platforms.

New Objectives, New Platforms

The author argues that the possibility of inter-state warfare nowadays in the region is quite low in spite of several ongoing border disputes and occasional inter-state incidents (e.g. Bolivia and Chile; Guatemala and Belize; Colombia and Venezuela). Nevertheless, crime is prevalent not just to dry land but also at sea. In the 21st century, a principal objective for Latin American navies will be to tackle maritime crime like drug trafficking, weapons trafficking, maritime pollution and, of course, illegal fishing.

The relatively low possibility of inter-state tensions and the rise of maritime crimes have an obvious effect in the acquisition of sea platforms. On the one hand, several nations will without a doubt continue to acquire platforms more suited for conventional warfare. For example, Brazil is constructing a nuclear-powered submarine while the Sao Paulo carrier undergoes repairs. Colombia recently purchased two (used) German subs while the Peruvian Navy, via recent agreements with Germany’s ThyssenKrupp AG and Israel’s Elbit Systems, is going to upgrade its four Angamos-class U-209 subs.

The author contends that the priority of regional navies is to constructor purchase small, fast, multipurpose vessels and OPVs in order to more efficiently patrol their seas and stop suspicious vessels. For example, the Uruguayan Navy plans to acquire up to three new vessels, likely OPVS from the German shipyard Lurssen, which would be the country’s largest acquisition of new sea platforms in years. The vessels will be the new cornerstone of the fleet and will be charged with patrolling Uruguay’s EEZ for maritime criminals, such as illegal fishing vessels.

Similarly, the Peruvian Navy has acquired a Pohang-class corvette from South Korea, the BAP Ferré, which will also be utilized for patrol operations. Additionally, the Peruvian state-run shipyard Servicios Industriales de la Marina (SIMA), has finished building two new OPVs for the Andean nation’s Navy, the BAP Río Pativilca and the BAP Rio Cañete. As a final example, the Mexican Secretariat of the Navy is also constructing OPVs to patrol its EEZ. Just last November, the Mexican Navy baptized the ARM Chiapas, constructed by the state-run shipyard Astilleros de la Marina.

Peru/SIMA Launches new patrol vessels BAP Cañete and BAP Pativilca (SIMA Peru)

While any of these platforms can also be deployed for conventional warfare if necessary, the acquisition of OPVs by several Latin American navies highlights changing strategies given evolving regional geopolitics and threats. Conventional conflict is always a possibility, but the clear and present maritime danger comes from criminals, not the possibility of an invading fleet a la Spanish armada. Hence, the ongoing wave of new purchases focuses on OPV-type vessels.

Concluding Thoughts

Between 12-17 June, the Royal Canadian Navy hosted the 27thbiennial Inter-American Naval Conference (IANC), which brought together representatives from 14 hemispheric navies. The topic of the conference was the “Future Maritime Operating Environment,” with a particular focus on maritime crimes, like drug trafficking, in the Caribbean Sea and Eastern Pacific.

In his remarks at the IANC, Admiral Marcelo Hipólito Szur of Argentina explained how demographic pressures and globalization will put greater pressure on the demand for natural resources, including those found in the oceans. He described how this will push governments to protect their (maritime) natural resources which could in turn lead to conflict between nations over yet-undefined maritime borders. It is beyond the scope of this article to discuss the possibility of future inter-state conflict due to issues like fishing rights, however it is certainly within the realm of possibilities, given unsolved differences between Latin American states and the non-violent “Cod War” between the United Kingdom and Iceland that serves as a recent precedent.

Nevertheless, the issue does stand that climate change and population explosion will increase the demand for maritime resources, which will foment bigger fishing operations, legal or not. It is safe to assume that fishing vessels crossing maritime borders without authorization is a problem that will continue, which will in turn lead to future incidents. The accusation that the sinking Chinese vessel tried to ram an Argentine ship brings up the issue if, in the worst case scenario, illegal fishing vessels become violent and attempt to attack isolated coast guard vessels, rather than attempting to flee. The author has not found incidents of fishing vessels shooting at OPVs or other security ships, as unauthorized ships prefer to flee or talk their way out of a possible arrest, but it is likely that violent incidents will eventually occur.

In order to counter ongoing maritime crimes, Latin American navies are devoting more time and resources to monitor and protect territorial waters. The acquisition of OPVs and patrol-type vessels by regional naval forces exemplifies the growing attention to this new maritime reality. Moreover, illegal fishing is also being addressed at forums for dialogue like the IANC and now there is even the FAO framework to help focus resources on this problem.

Illegal fishing may not make headlines as compared to drug busts in the Caribbean Sea, however this is an ongoing maritime crime that affects Latin American states and will continue to occur, if not worsen.

W. Alejandro Sanchez is a researcher who focuses on geopolitical, military and cyber security issues in the Western Hemisphere. Follow him on Twitter: @W_Alex_Sanchez.

The views presented in this essay are the sole responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of any institutions with which the author is associated.

Featured Image: ARC July 20 of the Colombian Navy. (webinfomil)