By Major Jeff Wong, USMC

Interwar-Period Gaming Insights and Recommendations for the Future

The militaries of Germany, Japan, and the United States utilized gaming between the First and Second World Wars to help them overcome challenges relating to doctrine, organization, training and education, and capabilities development. The Versailles Treaty prohibitions prompted Germany to use means other than live-force exercises to study and mature its combined arms concept, test naval and air doctrine, and drive planning for the invasions of Poland, France, and the Low Countries in the European theater. Japan effectively used wargames to inform doctrine and war planning, but biases affected game outcomes and subsequent planning of future campaigns, particularly the Battle of Midway. Japan gamed both strategic and tactical elements of its ambitious Pacific campaign, studying in detail essential tasks as part of its Pearl Harbor and Midway operations plans. Game insights prompted planners to change parts of its Pearl Harbor attack, but failed to sway leaders to examine more closely a critical element of the Midway campaign. The United States, particularly the Navy, combined wargaming with analyses and live-force exercises to study upcoming likely threats and advance naval concepts and capabilities such as carrier aviation. In the United States, Naval War College games of different variations of Plan Orange exposed officers to the theater, operational, and tactical challenges of a conflict against Japan. Many games played over the years between the world wars created a baseline of understanding about how naval officers would fight when war broke out. Now, nearly a century later, today’s U.S. military should apply best practices from those interwar years to spur innovation and overcome the kinds of strategic, operational, and institutional challenges that plagued these adversaries before the Second World War.

This is the final part of a three-part series examining interwar-period gaming. The first part defined wargaming, discussed its potential utility and pitfalls, and differentiated it from other military analytic tools. Part two discussed how the militaries of Germany, Japan, and the United States employed wargames to train and educate their officers, plan and execute major campaigns, and inform the development of new concepts and capabilities for the Second World War. This final part offers recommendations, taken from effective practices of this period, to leverage wargames as a tool today to provide a strategic edge for the U.S. joint force tomorrow.

Wargaming for Today

First, the U.S. military must expand and deepen the use of wargaming at PME institutions as a training and educational tool. Similar to the interwar period, wargames should be used to train officers to make decisions from a commander’s perspective, gain insights into likely adversaries, and learn about the war plans to counter or defeat them. Wargaming design should be part of the regular curriculum to reinvigorate this technique within the uniformed military, since PME institutions are intended to broaden officers’ professional horizons and allow them to explore new ideas.

At the interwar-period Kriegsakademie, some students had never experienced the brutal combat of World War I and never faced decision-making under fire. Wargaming woven throughout the curriculum gave these future leaders an opportunity to practice “commandership” from the commander’s perspective. Thus, students playing in wargames estimated situations based on given scenarios, outlined courses of action after assessing situations, executed plans, and then absorbed honest critiques of their decisions. In the 1920s and 1930s at the Naval War College, students also received a primer in commandership against the backdrop of a Pacific naval campaign. The students who played the games, as well as the faculty members who designed and umpired these events, shaped and fed a shared mental model about the strategic, operational, and tactical challenges of fighting the Japanese in the coming war. Officers returning to Newport as faculty members brought with them recent operational experiences, including fleet experiments that shaped carrier aviation and informed the requirements of new capabilities.

Beyond the Naval War College and the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California, current U.S. PME students are not taught how to plan and develop wargames as part of their regular course work. At U.S. Marine Corps University, for instance, wargaming is taught during a six-week elective at Command and Staff College (if enough students express interest in the elective), but the course fails to relate how games are relevant to real-world war planning and critical U.S. defense processes such as capabilities development.

At the next-level PME institution, students of the Marine Corps War College (lieutenant colonels and commanders) participate in a wargame as part of the curriculum’s Joint Professional Military Education II (JPME II) requirement, but they are never taught how to plan, execute, and analyze a game themselves. Within the Air Force, the Air Force Materiel Command offers three-day introductory courses with curricula tailored to the needs of a client command or organization, but these courses fall short of the integral nature that wargaming fulfilled for the German Army, Japanese Navy, and U.S. Navy during the interwar years.

To yield substantive benefits, wargaming must be integrated into service PME starting with captain-level career courses. The first exposure should be at the rank of captain in order to give young leaders intensive, virtual decision-making experience before they assume company command. Company command is the appropriate time to introduce gaming to an officer’s development because his unit gets four times larger (a Marine rifle company has 182 personnel by table of organization, compared to 43 personnel in a Marine rifle platoon) and he must have the mental acuity and confidence to operate without constant supervision from superiors. Gaming gives leaders this experience.

As an officer’s career progresses, the wargaming curriculum should teach students how to develop, plan, and execute wargames on a larger scale. At top-level schools, an officer should be expert at applying game insights into the vast U.S. military bureaucracy, feeding future-leaning commands and organizations within the supporting establishment that play a key role in developing future strategies, concepts, capabilities, and resource allocations. With its emphasis on decision-making and reflection on the implications of those decisions, wargaming provides a tool to foster imagination and intellectual growth inside and outside a formal schoolhouse setting. Teaching wargaming design to uniformed military members empowers them to create the intellectual venues themselves when they return to the fleet, flight line, or field – much like the officers of the German Army, Japanese Navy, and American Navy did during the interwar period.

Second, the U.S. military should more closely bind service-level wargaming, analysis, and live-force exercises to provide the intellectual and practical test beds to explore and develop new concepts, capabilities, and technologies to overcome unforeseen warfighting challenges. The games and exercises should be conducted as distinct events that are separated by weeks or months, unlike the infamous Millennium Challenge 2002 event, which attempted to synchronize a wargame, experiments, and exercises involving live forces around the world.

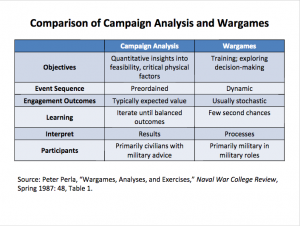

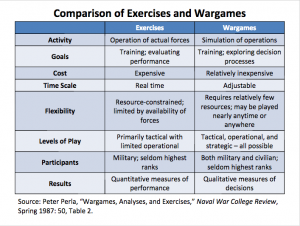

Wargames, analysis, and exercises are complementary elements of a cycle of research that offered fresh approaches and shaped new capabilities during the interwar period. Wargaming provides an environment for players to make decisions and understand their implications without expending blood or treasure. Insights derived from games are generally qualitative in nature. Analysis uses mathematical tools – primarily computer-generated models in today’s military – in an attempt to duplicate the physical processes of combat. Insights derived from analysis are usually quantitative in Both wargames and analysis, however, are only abstractions of reality. Together, they can inform exercises that give real forces the opportunity to implement in the physical domain the new approaches and ideas suggested by wargames and analysis. (See Table 1, Comparison of Campaign Analyses and Wargames.)

U.S. Navy Commander Phillip Pournelle writes that each of the tools “suffer from their own biases, simplifications, and cognitive and epistemological shortcomings. When integrated judiciously, however, the cycle of research gives leaders at all levels critical facts, synthetic experiences, and opportunities to rehearse a range of events in their minds and in the Fleet or the field.” (See Table 2, Comparison of Exercises and Wargames.)

The cycle of research has increased momentum at the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory’s (MCWL) Ellis Group, which hosts weekly wargames to examine emergent Marine warfighting challenges. The games serve as an incubator for concepts and capabilities under development. During a game in 2015, dozens of uniformed officers and civilian experts gathered around a large sandtable separated by a barrier. A young Marine infantry captain explained how he planned to land his company. On the other side of the barrier, red cell members – retired field-grade officers and staff noncommissioned officers – determined how they would oppose the landing. On the group’s periphery, analysts recorded observations made by the participants. Scribes filled whiteboards with insights from the game, which they matched against the command’s prioritized list of warfighting challenges. U.S. Marine Corps Brigadier General Dale Alford, MCWL’s commanding general, adopted the weekly games after observing the Naval War College’s Halsey Groups use operations analysis and wargaming to examine naval warfighting challenges. “It was mostly about getting the right people involved and in the same room,” he said.

Third, wargaming leaders must ensure an accurate and intellectually honest representation of the enemy. Most games played by the Germans, Japanese, and Americans during the interwar period featured two sides: friendlies and adversaries playing against one another. Some of today’s large service-level games are one-sided, with friendly “blue” actions being played against pre-scripted enemy reactions or a control group attention divided between representing “red” and running the overall event. However, if war is “an act of force to compel our enemy to do our will,” as Carl von Clausewitz suggested in On War, these games must adequately portray the adversary’s will. One-sided wargames lose the essence of the opposing will when the enemy’s actions are not represented by another human being seeking to win. Retired U.S. Marine Corps Lieutenant General Paul Van Riper, who previously served as director of Command and Staff College, required all Command and Staff College games to be two-sided affairs. “You need two free-thinking wills … within the bounds of the problem,” said Van Riper, who has consulted on many joint and service games since his retirement from active duty in 1997 and served as the red cell commander during the Millennium Challenge event.

This honest portrayal goes beyond using an expert versed on enemy (e.g., “red cell”) capabilities, limitations, and doctrine. During the Wehrmacht wargames before the invasion of France and the Low Countries, the red cell correctly suggested that French-led Allied Forces would be slow to respond to a German main effort thrust through the Ardennes – prompting planners to shift resources to the army group approaching from the forest. The red cell did not portray an idealized version of the French doctrinal response, which would likely have prompted German planners to shift resources to a different army group and resulted in a different course of action. From the Japanese wargames before the Battle of Midway, historians and professional gamers often cite the sinking – and revival – of two Japanese carriers as an admonition against biases, poor assumptions, and predetermined outcomes.

Fourth, future wargaming efforts should use different types of games for different purposes and desired outcomes. A greater variety of games can attack a problem from different perspectives. A larger number of games provides more opportunities to create fresh solutions. For a new, evolving subject, a wargame with more seminar discussion, less action-counteraction play, and fewer rules might be more appropriate in order to generate player insights and spur creativity. On a topic for which much is already known, a wargame with less seminar discussion, more action-counteraction play, and more rules based on hard data might be more suitable to refine players’ understanding of capabilities.

Back to the Future

The German Army, Japanese Navy, and U.S. Navy used wargaming to shed light on strategic, operational, and tactical uncertainty during the interwar period. In the German Army, wargaming formed the bedrock for the education of officers and provided opportunities for commanders and staffs to rehearse complicated operations such as the offensive against France and the Low Countries in 1940. For the Japanese Navy, planners utilized wargames to examine different ways to employ the Combined Fleet in the opening salvo of the Pacific campaign. The Germans successfully used red cells during their wargames to accurately and honestly portray French forces’ actions during the 1940 campaign, while the Japanese demonstrated the dangers of predetermined notions during wargames before the Battle of Midway. The U.S. Navy found wargaming to be an effective tool for educating officers as well, inculcating the practice among generations of officers who attended the Naval War College and fostering a shared mental model through hundreds of wargames that focused on a potential future war with Japan. Likewise, American naval officers also wargamed carrier aviation, discovering optimal ways to employ forces that massed firepower and extended the reach of the Pacific Fleet. These insights fed the cycle of research that allowed American naval officers to study, experiment, and develop new concepts and capabilities leading up to the Second World War.

Interwar-period wargaming provided users with a chance to shed light on an opaque future. Although the threats are different, senior U.S. defense leaders face similar ambiguity now. The reassertion of Russia in world affairs, a militarily stronger China, and a multitude of powerful non-state actors have dramatically changed the strategic landscape. Fast-developing capabilities, nascent technologies, unmanned weapons platforms, 3D printing, and human-machine interfacing are among the potential factors of the next great conflict. With no cost in blood and minimal in treasure, wargames can empower U.S. military leaders to exert intellectual leadership and innovate to be better prepared for the future.

Major Jeff Wong, USMCR, is a Plans Officer at Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Plans, Policies and Operations Department. This series is adapted from his USMC Command and Staff College thesis, which finished second place in the 2016 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Research Paper Competition. The views expressed in this series are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

1. Commander Phillip Pournelle, USN (analyst at the Office of Net Assessment, Office of the Secretary of Defense), interview by Jeff Wong, September 24, 2015.

2. As discussed previously, wargaming is different from COA Wargaming, which is a phase of the joint and services’ planning processes, e.g., the Military Decision-Making Process and Marine Corps Planning Process.

3. Colonel Matthew Caffrey, USAF (Retired) (wargame instructor at the Air Force Materiel Command), interview by Jeff Wong, October 15, 2015.

4. Gary Anderson and Dave Dilegge, “Six Rules for Wargaming: The Lessons of Millennium Challenge ’02,” War on the Rocks, November 11, 2015 (accessed April 1, 2016): http://warontherocks.com/2015/11/six-rules-for-wargaming-the-lessons-of-millennium-challenge-02/.

5. Philip Pournelle, “Preparing for War, Keeping the Peace,” Proceedings 140, no. 9 (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval Institute, September 2014), accessed October 15, 2015: http://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2014-09/preparing-war-keeping-peace.

6. Peter Perla, The Art of Wargaming, 287.

7. Brigadier General Dale Alford, USMC (commanding general of the Marine Corps Warfighting Laboratory), interview by Jeff Wong, November 23, 2015.

8. Carl von Clausewitz, On War ed. and trans. Michael Howard and Peter Paret (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1984), 75.

9. Lieutenant General Paul Van Riper, USMC (Retired) (faculty member at Marine Corps University), interview by Jeff Wong, February 2, 2016.

10. Pournelle, interview by Jeff Wong, September 24, 2015.

Featured Image: NEWPORT, R.I. (May 5, 2017) U.S. Naval War College (NWC) Naval Staff College students participate in a capstone wargame. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 2nd Class Jess Lewis/released)