By Major Jeff Wong, USMCR

Interwar-Period Case Studies – Germany, Japan, and the United States

By the beginning of the interwar years, wargaming had gained acceptance among military leaders in Germany, Japan, and the United States. For the German military, Helmuth von Moltke used wargames to train and educate officers at the Kriegsakademie during his tenure as chief of the Prussian and German General Staff from 1857-88. Generations of German Army officers accepted gaming as an essential part of training, educating, and developing leaders, and they continued the practice through the early years of the Second World War. In the late 19th century, German officers passed wargaming to their Japanese counterparts, who expanded the use of gaming for campaign planning and decision-making processes. Wargaming eventually became part of the regular curriculum at the Japanese Naval Staff College, and Japanese naval leaders attributed their success during the 1904-05 Russo-Japanese War to insights generated by these games. Students and faculty used wargames to test new ideas about tactical maneuvers, night attacks, fleet formations, principles of engagement, and supporting forces. Unlike the Germans, Japanese interwar-period games gained a deterministic quality, with officers using game insights as evidence to support courses of action that leaders had already favored. In the United States, a Navy lieutenant named William McCarty Little introduced gaming to the Naval War College in Newport during a series of lectures in 1887. The faculty experimented with the new technique in the ensuing years and incorporated it as a regular educational tool in 1893. During his interwar-period tenure as the president of the Naval War College, Admiral William Sims emphasized the need to test students’ decision-making abilities through the use of wargames: officers with otherwise strong reputations exposed their “lack of knowledge…of the proper tactics and strategy” in the war college game rooms in Newport.

This is the second of a three-part series examining interwar-period gaming. The first part defined wargaming, discussed its potential utility and pitfalls, and differentiated it from other military analytic tools.

Lessons from Germany: Kriegsakademie, Von Seeckt, and the Shared Mental Model

Wargaming realized its potential as a tool for learning in interwar Germany for several reasons. The PME system embraced gaming as a training and educational tool that encouraged introspection about decision-making and fostered subordinate initiative and adaptability. Senior benefactors valued wargames and the insights they generated. Wargames also contributed to a shared mental model about the strategic and operational dilemmas that the country faced upon the outbreak of war. The cultural indoctrination of wargaming expanded in German PME institutions, where officers played games to reinforce learning from lectures and seminars. Senior officers led students on staff rides that integrated elements of wargaming, forcing students to confront operational problems and formulate solutions. They conducted these staff rides and wargames in the regions of Central Europe that would become battlefields by 1939-40, including the areas adjacent to France and the Low Countries in the Second World War’s western theater and regions facing Poland and Czechoslovakia in the east. In order to graduate, every officer who attended the Kriegsakademie learned how to plan a wargame, execute the event, and apply insights toward future planning. After graduating and arriving at their parent units, officers found wargames to be an integral part of their continued maturation as military professionals. Every Wehrmacht unit from battalion or squadron upward conducted games as an intellectual substitute for live-force exercises, which had diminished in frequency due to funding shortages and troop-number restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles at the end of the First World War.

Senior benefactors in the German Army reinforced the importance of gaming. The post-war restrictions forced the newly appointed chief of the Reichswehr, Hans von Seeckt, to find different ways of ensuring the army adapted after The Great War so hard-won lessons could help inform how they would fight the next great conflict – an inevitability in the eyes of many German officers. In addition to ordering a sweeping review of the German military’s performance during the First World War, the German military chief turned to wargaming to prepare the next generation of officers.

Von Seeckt, an adherent of maneuver warfare, believed that German officers needed to understand the theoretical aspects of warfare to be prepared for a dynamic future battlefield. Wargaming became an essential element of that understanding. He expanded the term “wargame” to include other activities that resemble the modern-day TEWT and TTX, planning exercises (akin to the theater campaign planning central to the capstone “Nine Innings” exercise at the U.S. Marine Corps Command and Staff College), command-post exercises, and terrain discussions. By the end of von Seeckt’s tenure as chief of the general staff in 1926, Reichswehr officers examined Germany’s perpetual strategic dilemma – ensconced in Central Europe surrounded by potential adversaries – through wargames, with leaders at all levels immersing themselves in the details of existing plans, likely enemy reactions to German offensives, and the challenges of the physical terrain across Europe.

Other senior leaders who played wargames in this officer development system eventually used games to plan the opening stages of the Second World War. General Franz Halder, chief of the Army General Staff, commissioned dozens of wargames to examine different options for invading France and the Low Countries in 1940. General Ludwig Beck, chief of the German General Staff from 1935 through 1938, also employed games in his 1936 effort to prepare a new manual of modern operations for the entire army. After he and his advisers had decided on the principles they deemed most important in the new conditions of warfare of their time, they called on “seasoned officers” to test those principles using wargames. In the air, military aviation pioneer Helmuth Wilberg shaped future Luftwaffe operational employment through wargames during his rigorous critique of German air doctrine following the First World War. On the sea, German submarine force chief Karl Doenitz, a future grand admiral, utilized games to explore the employment of U-boats. Doenitz’s games generated new ideas such as wolfpack tactics and suggested that a three-hundred submarine fleet would be necessary to neutralize Allied merchant shipping in the Atlantic.

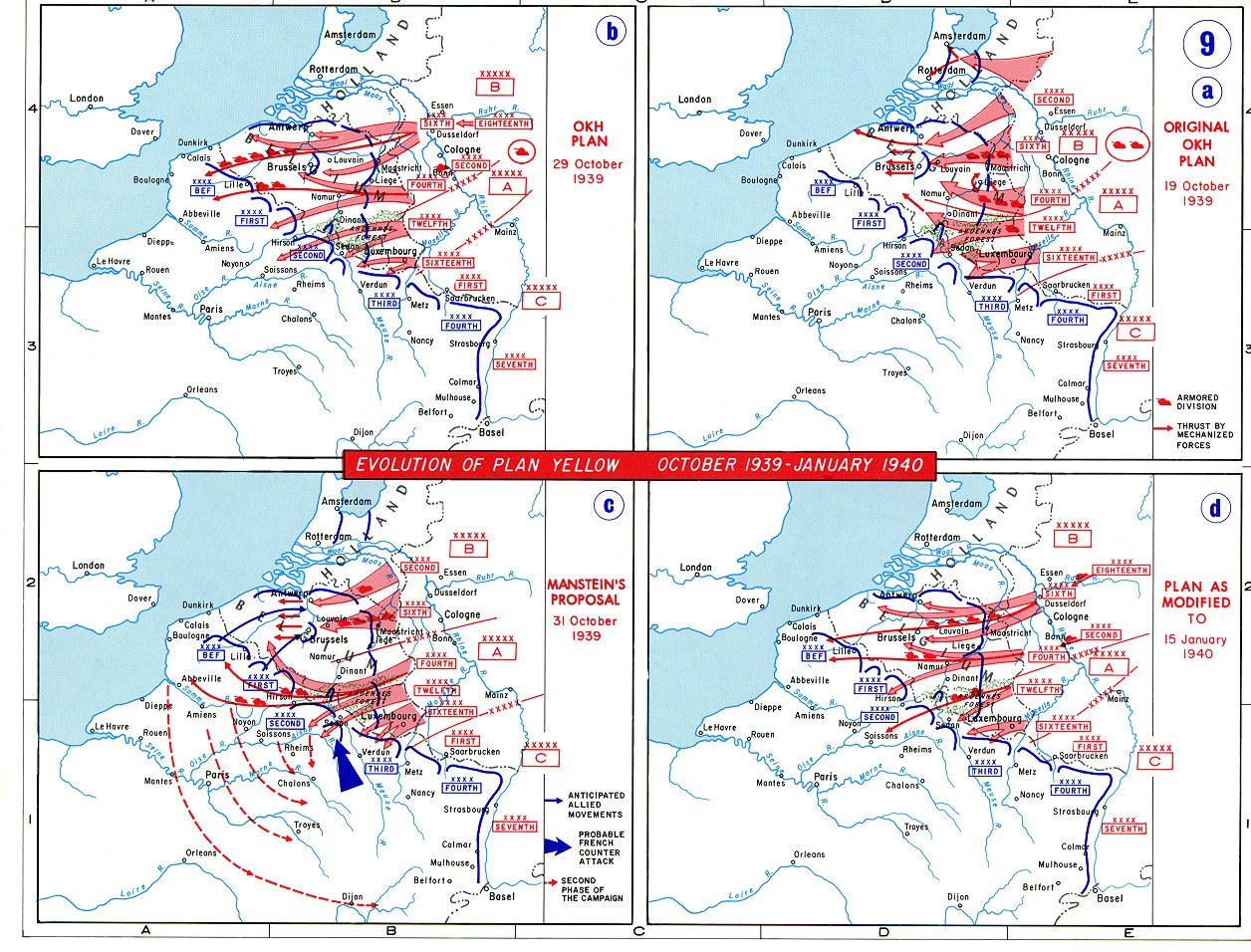

These wargames exposed strategic and operational dilemmas that fed a shared mental model for Wehrmacht leaders and their subordinate commanders. In this context, mental models comprise the collective tools, products, processes, and experiences that players use to make sense of the world. Games conducted prior to the invasion of France examined various iterations of Plan Yellow, the campaign to invade France and the Low Countries, and contributed to the German military’s shared mental model for how they would fight the next war. Among the numerous versions of Plan Yellow, the German Army General Staff settled on a daring version (some called it “reckless”) that feigned an attack on Belgium and the Netherlands. The feint would distract Allied Forces from the campaign’s main effort – an offensive through the Ardennes Forest that pushed German tank divisions across the Meuse River toward the English Channel, cutting off Allied lines of communication back to France. The wargames featured the services of Lieutenant Colonel Ulrich Liss, an expert on Western military doctrine who role-played as the commander of Allied Forces, French General Maurice Gamelin. Liss’ red cell accurately portrayed the likely Allied reaction – a slow response to a German main effort thrust through the Ardennes. “Liss had come to a view similar to that articulated by Hitler, namely that ‘to operate and to act quickly … does not come easily either to the systematic French or to the ponderous English,’” wrote Ernest May. Liss’ assessment during the games prompted Halder to eventually assign Schwerpunkt, or focus of effort, to Army Group A, which would push through the Ardennes. Colonel-General Gerd Von Rundstedt, commander of Group A, lamented that “the campaign could never be won.” However, the Germans did win, thanks partly to an insight generated by an accurate representation of the enemy as part of wargaming for the campaign. The Allied Forces failed to act quickly enough on the German deception until Group A’s divisions had crossed the Meuse on their way toward the English Channel.

In the spirit of Auftragstaktik, gaming helped establish the environment that fostered initiative among Wehrmacht subordinate commanders. Officers constantly examined and questioned the assumptions behind their own decisions in wargames, which fostered an environment that encouraged initiative and field innovation. Some subordinate leaders became less afraid to deviate from their original tasks and adjust to evolving situations during combat in order to meet their commander’s intent. During the offensive against France and the Low Countries in May 1940, after General Heinz Guderian’s Panzer Corps crossed the Meuse River at Sedan, he chose to press the attack west with all available forces and drive toward the English Channel, rather than make the doctrinally sound decision of slowing down and strengthening his corps’ bridgehead to the south. In another instance during the campaign, General Erwin Rommel’s Seventh Panzer Division neared the far end of the “extended Maginot Line” at the French-Belgian border – far ahead of his adjacent units – and lost radio communications with his corps headquarters. Rommel’s superiors never issued guidance for this stage of the operation because they did not predict their advance would proceed as quickly and successfully as it did. Like Guderian, Rommel pressed ahead with the assault and pushed his panzers west until he ran short of ammunition and fuel at Le Cateau. “German generals, even German colonels and majors, certainly felt freer to try new approaches and tactics than did their counterparts in the French army or (British forces),” wrote May.

In the Wehrmacht, commanders used wargames to assess their subordinates’ strengths and weaknesses under stress. They also used games to foster trust and understanding between senior and junior officers through teaching moments in the context of the game scenario. These games became “the best way for commanders to make known to subordinates their views on various aspects of warfare,” writes Dr. Milan Vego, a professor at the U.S. Naval War College. “Wargames were an important means for the ‘spiritual’ preparation for war and for shaping unified tactical and strategic views.” Through gaming, leaders established a climate that allowed for mistakes to be studied and encouraged subordinate commanders to adapt their plans to changing realities in battle. The Germans also utilized wargaming to examine evolving principles within the institution about combined arms, armor and maneuver, and air doctrine in order to inform capabilities development and national resourcing decisions that influenced, for example, the manufacture of close-air support platforms over long-range strategic bombers. By the mid- to late 1930s, Germany diverted limited resources to interdiction and tactical support aircraft because of the risk to ground assault upon the outbreak of war in Europe.

In the years after the First World War, wargaming remained a valuable training tool. During games, commanders stressed the importance of a proper commander’s estimate of the situation using imperfect information, logical decision-making, orders writing, and coherent communication of those orders. A game director would conduct a thorough after-action review with participants to discuss what drove commanders’ decisions during the game and offer alternate solutions. After the group adjourned, the game director worked with senior wargame participants to draft reports that identified issues for subsequent exploration in follow-on experiments, live-force exercises, and other wargames.

To complement insights gained from gaming, senior officers also used “operational mission” (Operativ Aufgaben) games to examine future hypothetical war scenarios. Led by senior officers within the Troop Office (or Truppenamtreise, the Reichswehr-era “general staff” entity), up to 300 officers from group commands, divisions, and the schoolhouses collaborated on a potential solution that was written as a study and submitted to the Truppenamtreise for review. In 1931, one such exercise examined a war with France and Czechoslovakia. Two others in 1932 outlined a campaign against Poland.

German interwar-years gaming enjoyed high-level support, cultural acceptance, and a shared mental model about the next Great War. Training and education that used wargames at the Kriegsakademie laid the foundation for officers to continue the practice at their units later in their careers. Believers such as Von Seeckt, Halder, and Beck integrated wargaming into strategic decision-making for the institution. In the supporting establishment, senior officers continued to wargame institutional issues such as doctrine, resourcing, and manufacturing of capabilities to fulfill projected future Wehrmacht requirements for the next war. German officers utilized wargames to first explore hypothetical strategic and operational dilemmas, then used lessons-learned to better understand campaign plans that served as the opening salvo of Germany’s Blitzkrieg in the European theater. Gaming fostered an environment that encouraged subordinate leaders to adapt, innovate, and develop creative solutions.

Lessons from Japan: Ugaki, Midway, and the Carriers That Wouldn’t Sink

The German example demonstrates wargaming’s promise as a learning and rehearsal tool, but lessons from the Japanese experience highlight potential pitfalls when the tool is misapplied, misinterpreted, or abused to support a predetermined outcome. The Japanese example highlights the benefits of integrating wargaming into the professional development of officers in the schoolhouse, but it also illustrates the potential dangers of unrealistic play and obfuscation of game outcomes.

Japanese planners examining the Pacific theater determined that a bold campaign that relied upon speed, surprise, and near-perfect synchronization would be necessary against American, British, and Dutch forces in Southeast Asia and the Western Pacific to establish strategic conditions favorable to the Japanese at the onset of hostilities. Games played a crucial role in supporting Japanese assumptions about the Pacific campaign. Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, directed wargames to support planning for the pivotal campaigns at Pearl Harbor in 1941 and Midway Island in 1942. By the beginning of the interwar period, officers learned gaming at the Japanese War College and Naval War College, just as German military officers did at the Kriegsakademie. Japanese naval officers first wargamed an attack on Pearl Harbor in 1927, when carriers and carrier-aviation capabilities were in their infancy. During these games, two Japanese aircraft carriers (the only ones available in the fleet at the time) supported by an advance guard of submarines, destroyers, and cruisers inflicted only minimal damage on the U.S. Pacific Fleet. Observers criticized the Japanese naval force commander’s decision to attack Pearl Harbor for being rash. Japanese officers continued to wargame to support planning as the army expanded operations into Manchuria and China, and planners intensified the practice starting in 1937 when they started shaping a campaign to defeat British forces in the South China Sea.

Wargames played an integral part of Japanese war planning, with the Navy hosting a series of games prior to the opening campaigns in the Pacific theater. These games included a theater-level wargame that examined the Army and Navy’s opening campaigns in the Aleutian Islands, Pearl Harbor, and the Southwest Pacific, as well as operational- and tactical-level wargames that focused on specific parts of the operations. Fleet commanders and selected staffers participated in several secret games held in fall 1941 in preparation for the Pearl Harbor attack, as well as a series of games played in early 1942 before Japanese attacks across the Philippines, the Aleutian Islands, Guam, the Dutch East Indies, Singapore, and Hong Kong that ultimately stymied U.S. and other allied forces across the region.

Planners used wargames conducted in the fall of 1941 at the Japanese War College to analyze the effectiveness of a surprise attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet in Pearl Harbor, as well as allow commanders and planners to rehearse the operation. For the Pearl Harbor wargames, Yamamoto handpicked his participants, which included fleet commanders and their staff. Yamamoto wanted the wargames to generate insights about three critical decisions as part of the attack. First, he wanted to determine the feasibility of the operation. Second, Yamamoto wanted to figure out if the fleet could achieve surprise in the attack. Third, he wanted to examine an optimal route for the approach of the carrier strike group toward Hawaii. Commander Minoru Genda, a trusted confidant of Yamamoto who served as an air officer of the carrier task force that would attack Pearl Harbor, said that the Pearl Harbor wargames “clarified our problem and gave us a new sense of direction and purpose. After they were over, all elements of the Japanese Navy went to work as never before, because time was running out.”

Japanese wargames also had vocal critics. Genda’s direct superior and the commander of the Pearl Harbor strike force, Admiral Chuichi Nagumo, expressed skepticism about the games’ insights about likely Japanese success against the American Fleet. Yamamoto favored a bold attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet and overruled Nagumo’s chief concern – that massing six aircraft carriers for the Pearl Harbor task force put a significant amount of overall Japanese naval combat power at risk. Vice Admiral Hansaku Yoshioka, among the participants of the Pearl Harbor games, decried the inflation of Japanese capabilities, underestimation of American forces, and umpire decisions that were slanted in favor of the Japanese. The games “epitomized the Japanese penchant for short-sighted, self-indulgent thinking,” Yoshioka told American interrogators following the war. World War II scholars believe this “self-indulgence” came back to haunt the Japanese during wargames before the Battle of Midway, when the Midway game series director, Admiral Matome Ugaki, overturned umpires’ rulings about the sinking of two Japanese carriers by American land-based bombers. Ugaki reduced the number of sinkings to one carrier and allowed the other to participate in the next part of the game – invasions of New Caledonia and Fiji Island.

Wargaming professionals often cite Ugaki’s umpiring during the Midway wargame as a prime example of a good wargame undermined by leaders with a deterministic bias, but the reality is that wargaming has limitations. A wargame is a good tool to examine decision-making, establish principles, develop insights, and recommend areas for further study. It is not a good tool for predicting the future or generating hard data. In The Art of Wargaming, Dr. Peter Perla reasons that while the Japanese Midway games were “almost certainly biased,” the point that is often overlooked is that the game “raised the crucial issue of the possibility of an ambush from the north; the operators ignored the warning, a warning reiterated by the oft-maligned Ugaki.” This fact suggests that changing the umpires’ ruling of the effectiveness of land-based bomber attack was not necessarily willful ignorance, since B-17s had attacked the Japanese carrier task force on several occasions and failed to score a single hit. Perla writes, “Ignoring or changing the results of a few die rolls did not constitute the failure of Japanese wargaming in the case of Midway; ignoring the questions and issues raised by the play did.” In this case, the wargame generated an insight that key leaders of the actual Midway campaign overlooked. Other Japanese planners believed the principal failure of the game was the “uncharacteristic” play of Captain Chiaki Matsuda, the Japanese officer who role-played as the American commander. In post-war interviews, Genda suggested that Matsuda mirror-imaged Japanese behavior onto the American fleet when it did not sortie for a decisive battle. “His (non-American) conduct of the wargames might have given us the wrong impression of American thinking,” Genda told interrogators.

Much like their German counterparts, Japanese planners during the interwar period integrated wargames into campaign planning. However, the primary difference appeared to be how the game’s sponsors and stakeholders interpreted the game outputs. In the Midway games, biases, poor assumptions, and preconceived notions caused analysts to overlook critical insights and misinterpret gameplay. Like the German wargame from the 1940 France campaign, which was notable for its honest portrayal of the Allied commander, Japanese wargames also show the importance of accurate, balanced “Red” play: the game must provide a correct picture of an adversary’s capabilities and limitations, then honestly portray how the enemy would fight in a given situation and environment.

Lessons from America: Newport, Carrier Aviation, and the Pacific Campaign

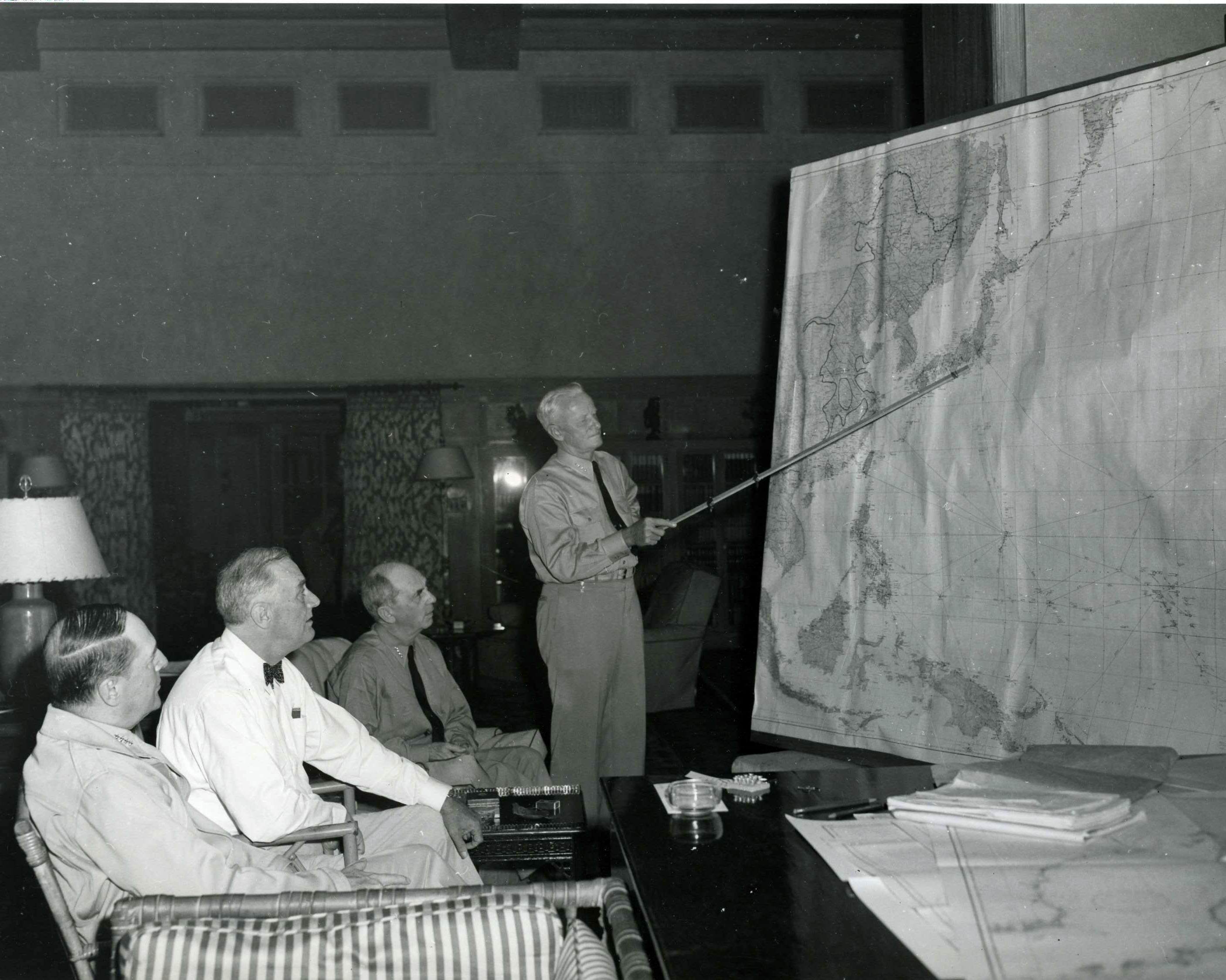

Nimitz understood the challenges of a war in the Pacific thanks to his experiences as a student in the game rooms of the Naval War College. So had Ernest King, William Halsey, and Raymond Spruance – future admirals who commanded task forces, groups, and numbered fleets in the Pacific against Japan. In the two decades between the world wars, U.S. Navy officers cycling between the Naval War College, the operating forces, and influential supporting-establishment institutions generated a shared mental model that focused on the challenges of an impending Pacific campaign against Japan. With the specter of another global conflict on the horizon, they participated in wargames, studies, and exercises in the 1920s and 1930s to explore the wide array of conceptual, operational, and tactical challenges that the bloody stalemate of First World War exposed.

The Naval War College is the most well-known illustration for American military gaming between the First and Second World Wars. Newport fully embraced wargaming by integrating it into officer PME curricula as the Germans did at the Kriegsakademie. The Newport wargames helped bolster student and instructor understanding about the challenges of operating in the Pacific against the Japanese, and informed studies and exercises for emerging capabilities such as naval aviation, which proved pivotal during the Second World War.

The Naval War College worked with the Navy’s General Board on future planning scenarios based on various competitors and capabilities. Officials assigned each scenario a color, including Plan Orange for a war with Japan, which formed the basis of many of the games played by students in Newport. Like other Naval War College students, Nimitz wargamed and studied these operational dilemmas during the 1922-23 academic year. In his thesis, Nimitz described the need for seizing advanced bases or developing an at-sea refueling and replenishment capability “to maintain even a limited degree of mobility” against the Japanese. “To bring such a war to a successful conclusion BLUE must either destroy ORANGE military and naval forces or effect a complete isolation of ORANGE country by cutting all communication with the outside world,” wrote Nimitz, referring to the color code-names for the United States and Japan, respectively. “It is quite possible that ORANGE resistance will cease when isolation is complete and before steps to reduce military strength on ORANGE soil are necessary. In either case the operations will require a series of bases westward of Oahu, and will require BLUE Fleet to advance westward with an enormous train, in order to be prepared to seize and establish bases enroute.” Thus, original conceptions of the Pacific campaign featuring the Pacific Fleet’s advance along extended sea lines of communication gave way to an island-hopping approach that allowed American forces to establish advance bases from which to launch air attacks against the Japanese home islands.

At the Naval War College, wargaming enjoyed a powerful benefactor in Admiral William Sims, who commanded U.S. Naval Forces in Europe during the First World War and began a second stint as president of the Naval War College in 1919. He possessed recent combat experience, knowledge of wargaming from his first term as the college’s president, and a sense of urgency to provide future leaders with more opportunities to test their combat decision-making skills and inform future naval innovation. Sims regularly highlighted gaming’s role in a naval officer’s professional development:

“The principles of wargames constitute the backbone of our profession. … In no other way can this training be had except by assembling about a game board a large body of experienced officers divided into two groups and ‘fighting’ two great modern fleets against each other – not once, or a few times, but continually until the application of the correct principles becomes as rapid and as automatic as the plays of an expert football team.”

The War Plans Division of the U.S. War Department gamed elements of American mobilization plans prior to the start of the Second World War, but the national PME institutions embraced gaming as an analytical tool, and none more enthusiastically as the Naval War College. Of more than 300 wargames conducted in Newport during the interwar period, about half focused on campaigns and tactics while the other half gamed theater-wide strategy. Among approximately 150 strategy games, all but 9 explored a possible war with Japan.

During games, students prepared plans based on a given scenario. Using their plans as a guide, players manipulated miniature ships on large maps depicting oceans of the world. Participants and umpires consulted charts and tables to determine game-move outcomes based on desired operational and tactical actions. During some games, students playing “Blue” – the United States – prepared and executed plans against classmates who attempted to mimic the doctrine and capabilities of the adversary – eventually Japan. In some cases, game directors ordered the players to switch sides and execute the plans prepared by their opponents. Tactical games proved useful in understanding and testing doctrines for ship movements, particularly the employment of carriers and their supporting vessels.

The college worked closely with planners at the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations (OPNAV) to incorporate elements of Plan Orange into the wargames. College officials sent game insights to OPNAV, which integrated them into the design of the fleet problems. The fleet tested the ideas generated by the wargames during the exercises, the results of which planners sent back to Newport to inform subsequent wargames. “Thus, ideas developed or problems encountered on the game floor were often examined during the fleet problems and vice versa,” wrote Alfred Nofi. For example, during Fleet Problem VII in 1927, war college students played a scenario identical to one being used by naval, air, and ground forces exercising in Rhode Island Sound and adjacent coastal areas.

The relationship between Newport’s wargames and subsequent analyses and exercises proved particularly valuable for the maturation of carrier aviation. In the 1920s, carrier aviation concept development began at the war college, where students and faculty used games to study existing and possible doctrine for fleet employment. The fleet took inferences drawn from the games and operationalized them in maneuvers and mock battles during the fleet problems. Analysts provided an honest evaluation of the exercise results back to the technical bureaus (particularly the Bureau of Aeronautics) and the war college, and the college refined subsequent wargames to reflect insights generated by the exercises. This feedback loop contributed to the realism and creativity of game play at Newport and ultimately led to conclusions about the massing of aircraft for strikes and the need for a coherent air defense plan that integrated anti-air artillery and defensive interceptors during the Second World War.

It is important to note that the wargames did not reveal the exact force structure, concepts, capabilities, tactics, techniques, and procedures that the U.S. Navy used to defeat Japan. Instead, the games gave American naval officers the analytic space to think and explore those issues. As the Pacific war proceeded, the U.S. Navy adjusted well to the changing realities of the conflict. John Kuehn wrote that the type of navy that America needed “had already been discussed and thought about extensively during the hearings of the General Board, in the classrooms at the Naval War College, at sea, and in the planning cells of OPNAV’s War Plans Division… Applying existing strategic, operational, and tactical solutions and then adjusting them to the realities of war came easier to Navy officers because of their focus over two decades on precisely the strategy and materiel requirements that a Pacific War without preexisting bases demanded.”

For the Americans, wargames allowed planners to explore evolving concepts and shape capabilities, as well as understand the operational challenges of the impending Pacific campaign. To develop new capabilities, wargames supported a cycle of research that informed analyses and live-force exercises in a continual feedback loop. This process reinforced realism in subsequent games and exercises, and a well-informed officer corps that tested and evaluated both types of evolutions. To develop a better understanding of Plan Orange, the Naval War College served as an incubator for creative ideas on how to overcome operational challenges in the Pacific. Through game play, officers learned how to fight against the Japanese, as well as how the Japanese fought. Students who cycled through the game floor at Newport developed a shared mental model that they carried with them to the fleet and eventually to war.

In Part Three, we will conclude this series by identifying best wargaming practices that can be applied to today’s U.S. defense establishment in order to prepare for future conflicts.

Major Jeff Wong, USMCR, is a Plans Officer at Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, Plans, Policies and Operations Department. This series is adapted from his USMC Command and Staff College thesis, which finished second place in the 2016 Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Strategic Research Paper Competition. The views expressed in this series are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the U.S. Marine Corps, the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

Endnotes

1. Milan Vego, “German War Gaming,” Naval War College Review 65 no. 4 (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, Autumn 2012), 110.

2. Francis J. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, 1961), 39.

3. David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2012), 73.

4. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 57.

5. Eric J. Madonia, “Preparing Navy Officers for Leadership at the Operational Level of War,” paper for the Naval War College (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College, March 5, 2010), 8.

6. Vego, 110-111.

7. Rudolf Hofman, “German Army War Games,” Art of War Colloquium (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, 1983), 6.

8. Vego, 114.

9. Ibid.

10. U.S. Marine Corps University, “About Exercise Nine Innings,” (Quantico, VA: U.S. Marine Corps University), July 20, 2015 (accessed March 8, 2016): http://guides.grc.usmcu.edu/9innings2015.

11. Ernest R. May, Strange Victory: Hitler’s Conquest of France (New York, NY: Hill and Wang, 2000), 258.

12. Peter Perla, The Art of Wargaming (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 42.

13. Phillip S. Meilinger, The Paths of Heaven: The Evolution of Airpower Theory (Maxwell Air Force Base, AL: School of Advanced Airpower Studies, 1997), 171.

14. Vego, 130-131.

15. May, Strange Victory, 465

16. Ibid, 258.

17. Ibid, 465.

18. Ibid, 263.

19. Auftragstaktik is an approach to command in which a commander issues to a subordinate an intent for a given mission, and the subordinate is given the freedom to independently plan and execute the mission. This mindset gave subordinates flexibility in deciding how to accomplish an assigned mission within the framework of the intent. Michael D. Krause, “Moltke and the Origins of the Operational Level of War,” Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, Michael D. Krause and Cody R. Phillips, eds. (Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 2005), 141.

20. Karl-Heinz Frieser, “Panzer Group Kleist and the Breakthrough in France,” Historical Perspectives of the Operational Art, Michael D. Krause and Cody R. Phillips, eds. (Washington, DC: Center for Military History, 2005), 173.

21. Ibid, 175-176.

22. Ibid, 176.

23. May, Strange Victory, 459.

24. Vego, 115.

25. Jonathan M. House, Toward Combined Arms Warfare: A Survey of 20th-Century Tactics, Doctrine, and Organization (Fort Leavenworth, KS: U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, 1984), 52.

26. Meilinger, The Paths of Heaven, 173.

27. Vego, 115.

28. Ibid, 129.

29. Ibid, 117.

30. Evans and Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887-1941, 469-470.

31. Martin Van Creveld, Wargames: From Gladiators to Gigabytes (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 168.

32. Ibid, 167.

33. Ibid.

34. Gordon W. Prange, At Dawn We Slept: The Untold Story of Pearl Harbor (New York, NY: Penguin Books, 1991), 225.

35. Ibid.

36. Ibid, 234.

37. Thomas B. Allen, “The Evolution of Wargaming: From Chessboard to the Marine Doom,” in War and Games, ed. Timothy J. Cornell and Thomas B. Allen (San Francisco, San Marino: Center for Interdisciplinary Research on Social Stress, 2002), 234.

38. Prange, At Dawn We Slept, 234.

39. Ibid.

40. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 40.

41. Ibid.

42. Perla, The Art of Wargaming, 47.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

45. Gordon W. Prange, Donald M. Goldstein, and Katherine V. Dillon, Miracle at Midway (New York, NY: McGraw Hill, 1982), 35-36.

46. Ibid.

47. Allen, “The Evolution of Wargaming,” 233-234.

48. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897-1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), 2.

49. Williamson Murray, “Red-Teaming: Its Contribution to Past Military Effectiveness,” DART Working Paper 02-2 (McLean, VA: Hicks and Associates, September 2002), 42.

50. Chester Nimitz, “Thesis on Tactics,” written for his master’s thesis at the Naval War College (Newport, RI: Naval War College, 1923), 35.

51. Admiral Sims is also the only active-duty U.S. naval officer to receive the Pulitzer Prize. During his second tour as the Naval War College president, he wrote Victory at Sea and won for history writing.

52. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 64.

53. Students at the Army War College, Army Command and General Staff College, and Marine Corps Command and Staff College also participated in wargames during the interwar period. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 53.

54. Van Creveld, Wargames, 166.

55. McHugh, Fundamentals of War Gaming, 53.

56. Van Creveld, 166.

57. John T. Kuehn, Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet That Defeated the Japanese Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008), 12-13.

58. Alfred A. Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923-1940 (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College Press, 2010), 20.

59. Ibid.

60. Williamson Murray, “Innovation: Past and Future,” in Military Innovation in the Interwar Period, eds. Williamson Murray and Allan R. Millett (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 316.

61. Kuehn, Agents of Innovation, 13.

62. Thomas C. Hone, Norman Friedman, and Mark D. Mandeles, “Innovation in Carrier Aviation,” Naval War College Newport Papers 37 (Newport, RI: U.S. Naval War College Press, August 2011), 157-158.

63. Murray, “Innovation: Past and Future,” 316-317.

64. Kuehn, Agents of Innovation, 178.

Featured Image: NEWPORT, R.I. (May 10, 2016)

Peter Pellegrino, U.S. Naval War College’s (NWC) senior military analyst for wargaming, briefs participants of a wargame reenactment of the Battle of Jutland at NWC in Newport, Rhode Island. During the wargame reenactment, Rear Adm. P. Gardner Howe III, NWC president, commanded the German High Seas Fleet and retired Rear Adm. Samuel J. Cox, director, Naval History and Heritage Command, commanded the British Grand Fleet.

(U.S. Navy photo by Chief Mass Communication Specialist James E. Foehl/Released)