Emerging Technologies Topic Week

Sections of the following article are adapted from a forthcoming master’s degree thesis, titled The Hunt for Underwater Drones: Explaining the Proliferation of Uninhabited Underwater Vehicles.

By Andro Mathewson

In late May 2021, the Israeli armed forces destroyed an armed underwater uninhabited vehicle (UUV)1 operated by the terrorist group Hamas. This kamikaze-UUV was used in an attempt to attack Israeli offshore gas and oil installations, which Hamas had unsuccessfully targeted in the past using rockets and uninhabited aerial vehicles (UAVs). This is possibly the first use of an armed UUV by a non-state actor, but UUVs have been in use since the 1950s, with the United States and Russia leading the charge. UUVs are now owned by over fifty nations across the world. Understanding why and how this technology proliferates is crucial to recognizing the role of such new technologies in international security and preparing effective responses. Based on this common understanding, the international community can counter further UUV proliferation by establishing a framework of norms and agreements, while security forces and military industries can focus on advancing effective counter-UUV technology.

Why Examine the Proliferation of UUVs?

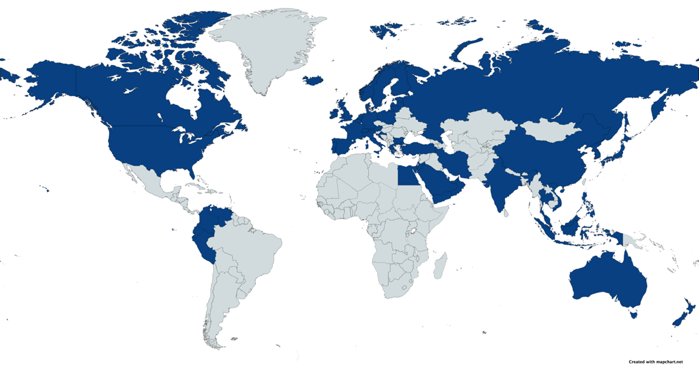

UUVs are becoming an important tool within the realm of international security. Naval forces across the world are quickly developing and acquiring a variety of UUVs due to their furtive nature, dual-use capabilities, and multifaceted functionalities. While the technology is still in relatively early development stages and leaves much to be desired, UUVs have quickly become an integral element of modern navies but also appear in the arsenals of lesser developed armed forces and non-state actors due to their utility as an asymmetric tool for sea denial. With advancements in intelligence gathering, surveillance, and reconnaissance technologies, UUVs are becoming essential assets in the maritime forces of states across the world. Although still predominantly used in an unarmed and surveillance capacity, UUVs have recently also been both adapted and designed to carry explosive ordnance and act in an offensive capacity. While the United States and Russia are at the forefront of UUV development, over fifty other states have either developed or acquired UUVs, as the following map shows.

Countries in possession of UUVs as of May 2021.2

There is also considerable interest in underwater drones and their diverse applications from militaries, private corporations, civil society organizations, and journalists alike.3 Their broad applications explain why the global UUV market size is projected to grow from USD 2.0 billion in 2020 to USD 4.4 billion by 2025. Despite the increasing interest in UUVs, many commentaries about their proliferation and use are based on speculation rather than on empirical analysis. Finally, examining the early proliferation of UUVs offers opportunities to explore, in-depth, the initial stages of a technology’s adoption by actors in the international arena, make predictions for the future, and prepare effective responses. While several of the patterns identified in this article might not persist moving forwards, it is nonetheless an opportunity to attempt to understand the wider motivations of governments and decision-makers on a global scale, including the role of security alliances, conflict, geography, economics, and international law.

UUV Proliferation

While at least 30 states have the indigenous capacity to manufacture UUVs, at least 55 states own or have previously owned UUVs.4 This demonstrates that there has been significant technology transfer and diffusion between states. UUVs, and the majority of the technologies they incorporate, are fundamentally dual-use, and the export thereof is often restricted by states and allowed only in a very small set of circumstances. For example, in 2009, the Egyptian Navy signed a deal under the United States Foreign Military Sales program for the delivery of the U.S.-based Columbia Group’s Pluto Plus UUV system, intended primarily for mine identification and destruction. More recently, in 2016, the United States donated two Remus autonomous underwater vehicles to the Croatian Navy to upgrade their countermine capabilities. While the majority of UUV proliferation is based on such authorized transfers between nations and global corporations or domestic development, there have been numerous cases of unwanted UUV technology transfer through smuggling, intellectual theft, and capture.

There are at least four documented cases of UUVs being seized either by nations or non-state actors. Perhaps the most prominent example is that of China seizing a USN UUV in the South China Sea in late 2016. However, this is not how China first acquired UUV technology, yet it is a possibility that the Chinese Navy deconstructed the UUV to understand and reconstruct the technologies within. While China later returned this drone, it had previously been able to smuggle protected American UUV technology via middlemen out of the United States. Other examples include the capture of a US Remus UUV by Houthi forces off the coast of Yemen in 2018, the seizure of an American early-model mine reconnaissance UUV in 2005 by North Korea, and the capture of a Chinese underwater glider by Indonesian fishermen in 2020. While it remains unknown if these captured UUVs were later remodeled to be operational by their new owners, these incidents showcase both a lesser-known method of technology proliferation and an inherent vulnerability of UUVs.

The legal status of UUVs is a factor that has presently had little influence on their proliferation, partially due to their relative novelty in the international arena as well as due to the currently very unclear legal boundaries concerning unmanned underwater vessels. However, due to the ability of regulatory systems and international law to limit said proliferation or direct it solely to allied states, essentially weaponizing both limitation and regulation, this unclarity is unlikely to continue. Additionally, the distinctive ethical character of war at sea generates several novel ethical dilemmas regarding the design and use of UUVs, which have yet to be answered by international law but certainly require attentiveness.

| Country | Likelihood of UUV Adoption |

| Romania | .886 |

| Libya | .812 |

| Chile | .780 |

| Slovenia | .751 |

| Argentina | .692 |

| South Africa | .653 |

| Algeria | .588 |

| Cyprus | .559 |

| Ukraine | .553 |

| Iraq | .462 |

Keeping track of new government acquisitions of UUV technology is an important first step in developing adequate responses. Thus, looking to the future, the database created for this article and the subsequent analysis thereof can help identify possible future adopters of UUVs.5 While exact foretelling is nigh impossible, the following table lists the ten most likely future adopters of UUV technology based on the author’s model. The majority of the nations listed have extensive military requirements. As UUVs become less cost-prohibitive and countries become wealthier, their proliferation may reach a tipping point where they become a widespread and almost ubiquitous technology, possibly following the route of UAVs, which are now present in almost every military across the globe. One other possible explanation for the future acquisition of UUVs by these listed states is their involvement in ongoing maritime disputes as UUVs are useful tools for monitoring vessel movements in contested spaces.

Responses to UUV Proliferation

Due to their relative novelty, both responses to their use and mitigation strategies are presently scarce. Countering global UUV proliferation should be an imperative for the United States Navy, its allies, and international organizations alike. Despite the clear recent increase in proliferation over the past decade, there are currently no national or international agencies in charge of a response to military purpose UUVs, while their ambiguous legal status has led to a de-facto underwater arms race. Nevertheless, there are two possible answers to these challenges: risk mitigation and counter-UUV technology. However, a dual-pronged approach addressing both simultaneously will most likely have the most effective results.

The first option relies on a rules-based international system and the adherence of states to international agreements and regulations. Risk mitigation strategies attempt to minimize the risk of conflict through international cooperation. In the case of military technologies, this is primarily via arms control agreements, the effectiveness of which is hotly contested. While arms control has been somewhat effective for several weapons, such as cluster munitions, its ability to restrict the proliferation of other uninhabited vehicles, such as aerial drones, has been generally deemed unsuccessful. Similar to UAVS, the place of UUVs in the international legal framework is highly uncertain. Many issues remain unanswered: Is a UUV part of its state of origin and thus immune from legal seizure by other nations? Should they operate only on the surface in another nation’s territorial seas? Can it legally operate there at all? (This is only a snippet of the many questions on UUV legality).

Deciding upon the legal status of UUVs in both domestic and international law is crucial for the security of states and the reduction of risk in the international arena. For example, classifying UUVs as ships or extensions thereof would categorize them under the rules of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This would allow UUVs to act correspondingly in the regions of the sea as determined by UNCLOS, illuminating where they may be legally deployed and for what reasons. Within the different zones, states could apply the rules currently affecting maritime vessels to UUVs, restricting the available legal actions of the UUV-controlling state. However, UNCLOS is not inviolable. Amongst many others, the United States has not ratified UNCLOS, reducing its coercive power. Many other states, including Russia and China, often criticize and neglect its stipulations. International law enforcement is also often ineffectual. Thus, although enforcing UUV use under the clauses of UNCLOS could alleviate some tensions, it is far from a panacea. Consequently, states must also develop more reliable defensive strategies and technologies to thwart antagonistic UUV deployments.

The development of counter-UUV technology is in its infancy, primarily due to two factors: the novelty of UUVs and the fact that they are predominantly still unarmed and used mainly for surveillance and intelligence gathering. However, the sooner the United States and its allies invest in and develop effective counter-UUV technologies and strategies, the more prepared they’ll be more future encounters. Due to the dual-use nature of UUVs, the true intentions behind their deployment are almost indistinguishable. Thus, states must prepare an extensive response toolkit, which requires both economic and political investments. Countering a technologically advanced threat requires the development of new defense mechanisms. In the case of UUV’s this could be new countermeasure methods of detection, tracking, and tracking – for example – acoustic or magnetic tripwires, to determine underwater movements through sensitive passages like harbors or straights. Another option is a more aggressive approach, such as the development of new systems to capture or outright destroy UUVs operated by adversarial states, including more precise torpedoes or more advanced naval mines capable of targeting and destroying UUVs.

Conclusion

The current status of aerial drones and their widespread use across the world offers militaries, policymakers, and international organizations the opportunity to prevent a similar scenario from occurring with underwater drones. While UAV technologies come with certain benefits to state military forces, such as surgical precision airstrikes, their indiscriminate use by non-state actors and terrorist groups has wrought havoc across the Middle East. Preventing a similar outcome with the continued proliferation of UUVs is vital to the security of the global ocean and the ships upon it. This will require concerted efforts and significant international cooperation from governments, international organizations, and civil society groups alike. While the successful control of UUV proliferation is not impossible, states must also prepare for the adverse outcome and develop effective and efficient counter-UUV strategies and technologies.

Andro Mathewson is a Research Fellow at the Arctic Institute, a Capability Support Officer at the HALO Trust, and an International Relations MSc student at the University of Edinburgh. His dissertation explores the proliferation of uninhabited underwater vehicles (UUVs) on a global scale. He is interested in international security, military technologies, and naval warfare. Andro has previously contributed to the Bulletin of Atomic Scientists, the Texas National Security Review, the Wavell Room, and the UK Defence Journal. Before his current studies, he was a research fellow at Perry World House at the University of Pennsylvania, where he also received his Bachelor of Arts in PPE and German. The views expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official position of The HALO Trust.

Endnotes

1. For the purposes of this article, the term uninhabited underwater vehicles (UUV) will be used throughout. There is no generally accepted nomenclature, thus “UUV” in this paper will encompass all types of uninhabited underwater vehicles, regardless if armed, unarmed, military, civilian, autonomous, or remotely operated. UUVs are also known as underwater drones or undermanned underwater vehicles and include autonomous underwater vehicles (AUVs), remotely operated underwater vehicles (ROUVs), and underwater gliders. However, it is also important to note that this essay focusses exclusively on government owned UUVs.

2. The map illustrates states and their militaries that are in possession of UUVs, regardless if those are armed or not, or how they were acquired (developed, bought, co-owned, transferred, or captured).

3. Part of this is driven by their dual-use nature and multifaceted abilities, including, for example, wreck salvage and environmental survey, as well as by the growing number of deep-water offshore oil & gas production activities and increasing maritime security threats.

4. This data is based on an original cross-sectional database produced in May 2021, containing information on the UUV capabilities of 196 states and 2 non-state actors. I use the term “at-least” for two reasons: (1) Due to the military nature of UUVs, it is safe to assume that there is significant information pertaining to their proliferation that is publicly unavailable, and (2) despite extensive research, there is always the possibility that there are lapses in my data.

5. To analyse this data, I use a probit regression model, focusing on two dependant variables (government UUV ownership and domestic production capacity) and the following independent variables: Access to the global ocean; Ratification of the United Nationals Convention on the Laws of the Sea; Submarine ownership; UAV ownership; NATO membership; Ongoing Maritime Disputes; Military Expenditure; and GDP per capita. This model shows an estimated probability that a state with a set of particular characteristics (the independent variables) will either own UUVs or have the domestic capacity to produce them. Based on this model, the list shows states most likely to acquire UUVs next, compared to the overall characteristics of states already owning UUVs.

Featured Image: Unmanned underwater vehicles, assigned to Commander, Task Group 56.1, are pre-staged before UUV buoyancy testing. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Julian Olivari/Released)