Emerging Technologies Topic Week

By J. Noel Williams

“The fundamental error in a debate over robotic development is to think that we have a choice. This world is coming, rapidly coming. We can say whatever we want, but our opponents are going to take advantage of these attributes, and that world is likely to be sprung upon us if we don’t prepare ourselves.”—Captain Wayne Hughes Jr. USN (ret).

Today’s maritime security environment recalls the early days of the United States Navy, when its economic and geographic limitations helped create a technologically bold yet focused fleet architecture. Just as the United States Navy couldn’t out build its rivals then, it can’t out build the Chinese Navy today. Even so, by drawing from its best traditions, and implementing a fleet design incorporating mission agile platforms and platform agile payloads, the Navy and Marine Corps team can affordably produce a fleet and fleet Marine force fit for purpose – even as those purposes change with the decades.

Past as Prologue

While naval forces made important contributions during the Revolutionary War, it wasn’t until the First Congress established the Revenue Cutter Service in 1790 and the Third Congress passed the Naval Armaments Act in 1794 that solid and enduring foundations were laid for the modern Coast Guard, Navy, and Marine Corps.1

In the last decade of the eighteenth century, it took very specific and dramatic demands for a divided and parsimonious Congress to pass any legislation that expended substantial resources. The Revenue Act was driven by the economic necessity to collect customs duties and taxes, and to protect against smuggling close to home. The Naval Armaments Act likewise was born of the economic necessity to protect the overseas trade threatened by piracy and the depredations of the British and French navies. In 1794, marine insurance premiums for transatlantic shipping rose to 25% of total cargo value.2 This expense impacted both shippers and farmers, thus providing a broad-based coalition in Congress for action.

The Algerian xebecs, polacres, and feluccas, the FAC/ FIACs of the era, were fast enough to overtake most American merchantmen, allowing them to commandeer the ships and enslave their crews.3 These pirates could act with impunity because the United States had no ships capable of addressing such a distant threat. British and French ships harassed U.S. flagged vessels without consequence.

Fortunately, American innovators would leverage new technologies to answer these operational challenges. Congress solicited proposals for the design of six frigates; Joshua Humphreys, a Philadelphia Quaker, answered the call with a bold new warship. Humphreys proposed a unique design for a very stout frigate that could carry thirty 24-pounder long guns on the gun deck, which he calculated would allow the ship to challenge European ships of line in stormy weather conditions and outrun any ship posing a substantial threat. Many objected to Humphrey’s radical design, but he countered with a response especially relevant to our current circumstances. He said, “It is determined of importance to this country to take the lead in a class of ships not in use in Europe, which would be the only means of making our little navy of any importance. It would oblige other powers to follow us intact, instead of our following them…It will in some degree give us the lead in naval affairs.”4

Humphreys deserves tremendous credit for being not only a genius in the details of ship design but also in the larger strategic context and operational functions that influence ship design. The British naval historian, N.A.M. Rodger, would say he knew how to build a ship “fit for purpose.” According to Rodger, “The proper question to ask of all ship designs is not how well they compared with one another, but how well they corresponded to each country’s strategic priorities, and how wisely those priorities had been chosen.”5

Techno-Strategic Environment

Rodger’s question is the central consideration for today’s Naval Services (the United States Coast Guard, Navy, and Marine Corps). It is critical that strategy-derived functions and missions, operating concepts to accomplish these missions, and technological opportunity guide the development of naval forces to realize a fleet fit for the purposes required by national, defense, and military strategies. Measuring the benefit of a new platform by comparing its performance to its predecessor or comparing a class of ship to an adversary’s like ship class does not answer the question.

The Naval Services have a broad portfolio: They must ensure unhindered access to the global commons for trade and travel; they must be able to project power into regions and countries posing a security threat to the U.S., its allies, or its interests; and they must defend the homeland while also deterring nuclear and conventional conflict.

While the eleven technology priorities identified by the Department of Defense (fully networked C2, 5G, hypersonics, Cyber/Info warfare, directed energy, microelectronics, autonomy, AI/ machine learning, quantum science, space, biotechnology), are essential areas for investment, the Naval Services must efficiently and effectively harness relevant emerging technologies to ensure an appropriate fleet design in the manner U.S. Navy recognized the power of the airplane in the 1930s and changed the fleet design to incorporate the aircraft carrier. How the Naval Services approach, develop, and implement these technologies must be in the service of strategy-driven objectives.

The underlying technologies that have made the smart phone possible, namely microelectronics and efficient power storage, will be a motive force driving fleet design just as the airplane influenced last century’s fleet. Strong commercial appeal has led to huge private investments driving the rapid evolution of these technologies, all of which are highly relevant to military communications, sensors, and weapons systems.

Of the 11 DoD tech priorities, only directed energy and hypersonics are not robustly addressed by commercial consumer interests. This means the DoD must ensure its priorities for basic research are weighted accordingly – leveraging and adapting commercial S&T in the nine areas with heavy commercial sector investment, and focusing additional resources on directed energy and hypersonics.

Operation Environment

Ubiquitous surveillance will have a profound effect on naval warfare. The range of modern surveillance methods, from HUMINT, social media, to an ever-expanding range of technical systems across all domains means that potential adversaries will likely know the general location of large ground formations and surface platforms. This operational environment is coming in the immediate future – despite robust signature control efforts. It is critical that this premise consistently inform systems acquisition and operational planning.

The Navy defines this environment as Tactical Situation 2 (TACSIT 2): the enemy lacks the precise location of blue forces, but knows their general whereabouts. This should be a threshold metric for force planning—a force designed to survive and win under constant surveillance. As the range and capability of intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance systems continues to expand, it will be increasingly likely that peer adversaries will often know exactly where friendly forces are located – in Navy terminology, TACSIT 1. Thus, a force that thrives in TACSIT 1 should be the Navy’s ultimate force design objective metric.6

The Distributed Maritime Operations (DMO) concept demonstrates a recognition of the importance of these metrics, but the concept has yet to substantially modify fleet composition toward more numerous, smaller surface platforms, more submarines, fewer aircraft carriers, and more unmanned systems.

If the increasing level of surveillance is combined with evolving smart munitions that only require an approximate location for launch (given their ability to autonomously seek or receive in flight updates), then planners must assume that surface forces and large land formations are always targetable, regardless of signature management efforts. For the purpose of naval force design, friendly forces in range of adversary threat weapons system must be assumed to be targetable.

This does not mean that signature management is a fruitless endeavor. Naval forces must continue to focus on signature management—not to defeat broad area surveillance intelligence surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR), but to defeat incoming enemy precision munitions in their terminal guidance phase. When coupled with electronic and physical decoys, military deception (MILDEC), obscurants (e.g. carbon fiber chaff), it will becoming increasingly difficult for the adversary to achieve a hit, provided that patrol locations are carefully managed based upon adversary weapon ranges and capacities. For ground-based missile systems, adding the ability to move rapidly into covered and/or concealed positions will allow these ground forces, likewise employing MILDEC and obscurants, to remain forward within the enemy’s weapons engagement zone. Refining these capabilities and associated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) is vital, given that munitions using onboard artificial intelligence will soon individually possess the equivalent of a self-contained battle management system.

While defeating wide-area surveillance will be extremely difficult, designing a force to be survivable by addressing terminal phase vulnerability is a tractable problem. As Hughes and Girrier state in Fleet Tactics, “…a single countermeasure anywhere can break the chain of measures necessary for an attack.”7 While it is prudent to assume our general locations are known and targetable, with the right force design (low-signature, dispersed, attritable, and leveraging unmanned systems) and force posture (distant enough to allow adequate time for spatial displacement based upon counterfire time of flight), one can make the opponent’s terminal attack challenge exceedingly difficult and thus avoid being unacceptably vulnerable.

How to Dodge a Bullet

The tactical objective is not to defeat broad area surveillance, but to defeat successful execution of the terminal phase of the precision fires attack.

Once again, new technologies are making range an especially critical determinate in naval warfare. This phenomenon was the driving force behind the dreadnought competition of the last century when the rapidly increasing range and effectiveness of torpedoes, guns, and fire control argued for larger caliber guns to be able to engage adversaries at the maximum possible range.8 Ever larger caliber guns were sought that could out-range adversary ships and overcome their protection, with the intention of being able to strike and neutralize an opponent before they were able to respond. While it is preferable to be able to attack with impunity, limiting the quantity of adversary munitions that can reach friendly forces is the next best choice. Because the densities of adversary weapons will decrease with distance, the greater the distance from which a friendly force can strike, the fewer adversary munitions will be available for counterbattery response.

There are also considerations unique to Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations. Certain ships, like battle cruisers, were designed with large guns but reduced protection to facilitate speed, either to overhaul slower vulnerable targets or to outrun larger, better armed and protected battleships. Given their inherent vulnerability, battle cruisers had to choose their fights carefully. Similarly, close consideration must be given to engagement geometry when striking targets from an Expeditionary Advanced Base.

Unlike a ship that can steam away to escape the range fan of an adversary, an EAB can only relocate limited distances to avoid attack. Because they remain within a “beaten zone,” the EAB force could be susceptible to pummeling attack. Thus, a system of EABs must have adequate munitions to substantially reduce the adversary’s systems or be prepared to accept attack, perhaps persistent attack, if its initial salvo does not substantially attrite the foe. It will be necessary to understand the breakpoint where the initial salvo of EAB munitions are sufficient to adequately attrite the adversary such that the return salvo can be successfully defended against or that adequate time is available for displacement. Of course, if friendly missile forces can outrange the adversary in the first instance, then their survivability is assured, so long as the adversary cannot close the distance or employ longer-range munitions from another platform.

If friendly forces attack within range of enemy counterfire, but their weapon’s time of flight is roughly 10 minutes or greater, shore-based batteries can find cover and concealment while also deploying physical and electronic countermeasures. This key distinguishing feature makes shore-based expeditionary anti-ship assets a unique contribution to the naval campaign.

Thus, longer range munitions cover more target area, increase the chances of outranging enemy counterfire, and buy time to effectively employ survivability countermeasures against counterfire. For all these reasons, DoD investment decisions should preference long-range offensive munitions and the smallest, most efficient platforms possible to deploy them.

Technology and Fleet/ Force Design

Technology is creating increased capability in ever smaller form factors, and this has profound implications for our fleet and force designs. It will require mission agile platforms and platform agile payloads.

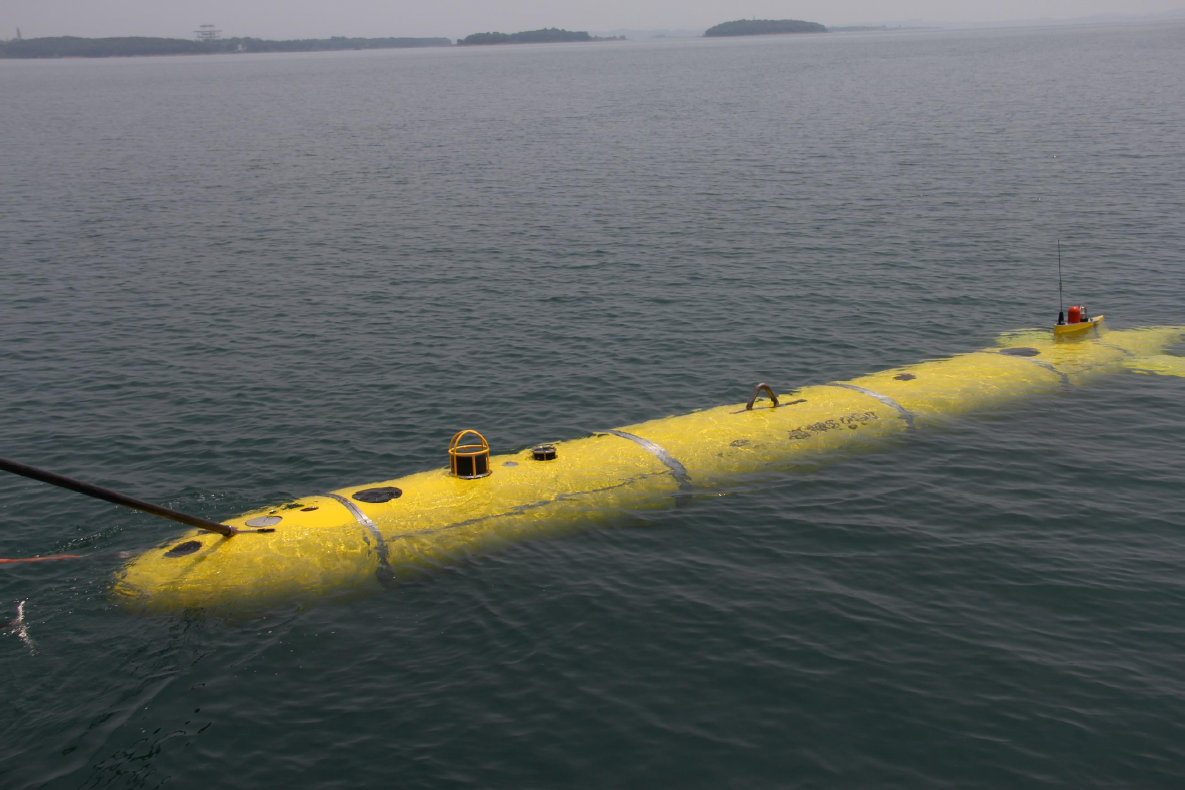

As the name implies, a mission agile platform is easily configured for a range of missions. This agility can come in two varieties. The first would be the quickest and is made increasingly possible by the fact that unmanned systems in all physical domains will be the primary sensors and weapons systems of future fleets, making larger more traditional platforms primarily carriers of unmanned systems. Flight decks, well-decks, and open storage spaces would allow mission agile ships to shift mission by simply changing the load plan. The second variety will be more strategic and will allow for reconfiguration of the ship’s systems themselves to adjust to longer-term mission and technology trends. Such modifications would be performed during shipyard availabilities.

Given the centrality of unmanned systems operating in all physical domains, a mission agile ship would be configured to accept a wide-range of payloads and offer robust interfaces to air, surface, and subsurface with flight decks and dry or well decks, side stages, or other apertures. As a matter of design, this reconfigurability would not be like the previously envisioned LCS modules. As discussed above, operational tailoring, unlike the original LCS plan, is about taking on payloads that deploy offboard. Reconfiguration of ship’s system, again, would be a more deliberate affair, focused on maintaining fleet relevance by offering an alternative to current acquisition approaches that yield decades-latent solutions.

Thus, the right fleet design offers both operational and strategic tailoring options. Agile ships would have multiple busses to provide for physical, electrical, and electronics interconnections. For example, a modular vertical launch system would allow for mission configuration but, could also potentially facilitate reload by pulling empty modules (such as several missiles in a module) and replacing it with a full one, thus simplifying packaging, transfer, and handling for expeditionary reload. This sort of forward reload would require a forward operating base or perhaps a large semi-submersible platform to allow a ship to drive under and have modules lowered into place, akin to the Mobile Offshore Base concept of the early 2000’s.

A fleet of small (<4000 tons), medium (<8000 tons), and large mission agile platforms (>8000 tons) would obviate the need for certain specialized platforms such as amphibious ships, thus the majority of the fleet could be tailored to a rapidly changing strategic environment given that these ships have space for different payloads, for example landing craft for an amphibious mission or unmanned surface or subsurface vessels for a sea control mission. This would provide options for increasing fleet fires in one instance and in another, provide scores of ships with amphibious, HA/DR, or engagement capabilities that would be especially relevant for grey zone operations and working with allies and partners. Some subset of these vessels should be ice hardened for operations in the polar regions. A fleet of such platforms would achieve far greater efficiency by greatly reducing ship specialization and therefore allowing a smaller fleet to have the effectiveness of a larger fleet.

Platform agile payloads (especially unmanned systems) are the natural complement to their host, a mission agile platform. Expeditionary logistics ships could be designed for the purpose of carrying and installing payloads forward.

Ubiquitous non-organic sensing, long-range, and loitering precision munitions reduce the size requirements for platforms. Most of these new, networked, and smaller platforms could forego crews and large radars with distinctive signatures. Removing just these two variables opens the design space substantially. Numerous, smaller, connected platforms would achieve efficiency and resiliency. Smaller platforms are cheaper platforms and can be produced in many more shipyards than a fleet of complex capital ships. Simply beginning the shift away from the aircraft carrier would make adequate resources available to evolve the fleet within current top-line budget constraints.

Technology trends will result in a fleet whose platforms are more numerous and more unmanned, carrying loitering munitions with the capacity for organic scouting. The Douglas SBD Dauntless was a potent armed reconnaissance platform in the Pacific Theater, playing a significant role at Midway.9 Loitering munitions are the SBD of today – providing scouting and lethality in one package, but with fantastically more precision and endurance.

The speed of engagements will be vastly quicker as hypersonics enter the inventory. To survive, platforms will need to stay at extended ranges, just as in the battleship era. Greater range will allow for response times to engage the threat weapon in multiple phases (e.g. boost, glide, terminal), and to employ military deception measures, obscurants, and non-kinetic countermeasures.

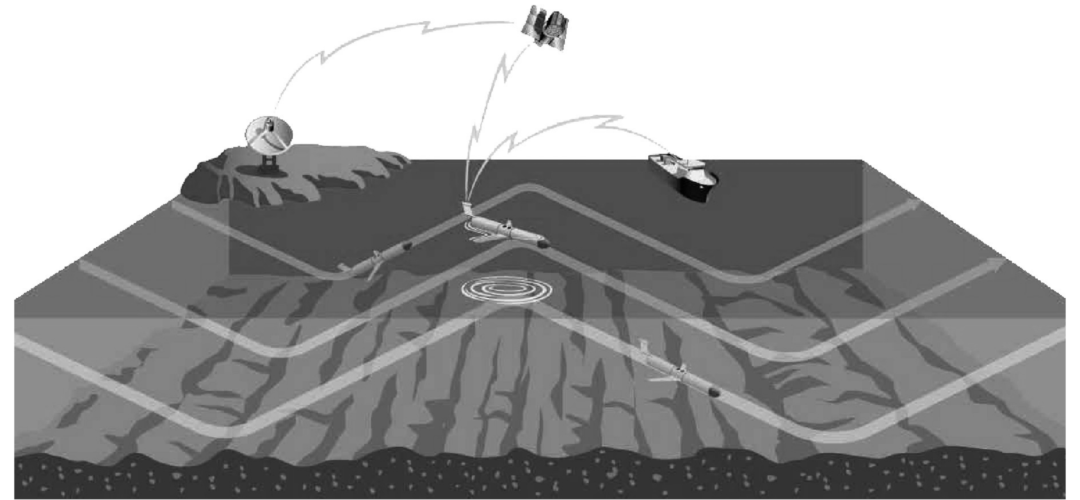

Multispectral sensors are continuing to increase in capability and decrease in size, while their platforms gain ever more endurance. Space and airborne platforms receive a great deal of attention, but subsurface sensors are developing rapidly and will challenge the U.S. Navy’s once unassailable domain advantage. The number and type of sensors that can be deployed affordably to detect friendly submarines and conversely those employed to detect adversary subs must be key considerations in developmental efforts.

Conclusion

In the 1930s, aircraft spotting increased gunnery accuracy by 200%.10 While we can’t know what percentage improvements in accuracy we will see in the future, we are so close to perfection that the actual percentage matters little. The Joint Force already possess a family of networked sensors revolutionizing scouting analogous to aircraft revolution in the first decades of the 20th century.

A capable battleship on the eve of World War II could fire eight tons of ordnance twice a minute, but at its maximum range of thirty thousand yards, it had a hit rate of only 5%.11 As Hone states, “Five percent of sixteen thousand pounds (eight tons) is eight hundred pounds. By 1941, one dive-bomber carrying one bomb weighing one thousand pounds could knock a carrier’s flight deck out of action-and do it from a range of 150 nautical miles.”12 Once this level of performance was achieved, and a war clarified the demand, no traditionalist arguments for the big guns could resist the inevitability these numbers portended. The efficiency of the aircraft was indisputable, and the only reasonable remaining battleship mission was shore bombardment. We are at such an inflection point today when manned aircraft begin to recede to different roles, while missiles and their supporting strike complex come to the fore.

The United States can field a Fleet and Fleet Marine Force vastly more effective than today’s fleet design. It is not about more money; it is about smart design fit for purpose. Humphreys would surely agree.

Noel Williams is a Fellow at Systems Planning and Analysis and provides strategy and policy support to Headquarters U.S. Marine Corps.

Endnotes

1. Ian Toll, Six Frigates, Norton, NY, 2006, p 43.

2. Toll p42.

3. Toll p36.

4. Toll p53.

5. N.A.M. Rodger, The Command of the Ocean, Norton & Co., NY, 2004, p. 409.

6. Commander Bryan Leese, USN, Living in TACSIT 1, Feb 2017 Proceedings

7. Captain Wayne Hughes Jr and RADM Robert Girrier, Fleet Tactics and Naval Operations third edition, Naval Institute Press, 2018, p 100.

8. Barry Gough, Churchill and Fisher Titans at the Admiralty, Seaforth Publishing, 2017, p 71.

9. Thomas Hone and Trent Hone, Battleline: The United States Navy 1919-1939. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2006, p81.

10. Hone, p81.

11. Hone, p97.

12. Hone, p97.

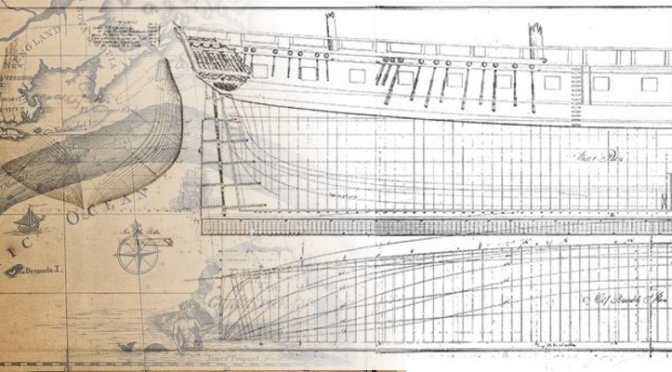

Featured image: Composite of: “A chart of the Gulf Stream” by Benjamin Franklin and James Poupard, (Philadelphia, Pa. : American Philosophical Society, 1786?); and, “Sheer, Half Breadth and Body Plan” after Joshua Humphreys’ 1794 design, depicting the structure of the three 44-gun frigates, United States, Constitution, and President (Courtesy Naval History & Heritage Command Detachment Boston, image hosted at USS Constitution Museum).