By Dylan “Joose” Phillips-Levine and Trevor Phillips-Levine

Turmoil has engulfed the Galactic Republic. The taxation of trade routes to outlying star systems is in dispute. Hoping to resolve the matter with a blockade of deadly battleships, the greedy Trade Federation has stopped all shipping to the small planet of Naboo, rich in raw materials vital to the economic health of the Republic.1

A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away… Trade Federation officers must have read Alfred Thayer Mahan’s naval classic, The Influence of Sea Power Upon History. In true Mahanian fashion, the Trade Federation massed their capital battleships to blockade Naboo.2 The Trade Federation pays homage to the East India Company that once controlled the trade routes and paved the way for Britain to become a world power.3,4 In The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, Mahan believed that sea control could be gained in part by blockades – an observation borne out by Great Britain’s ascent as an economic and military powerhouse.5 Renowned navalist Milan Vego offers further guidance of how to ensure sea control in his canonical book, Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice.6 In it, Vego demonstrates through historical examples that sea control can be achieved by strategically positioning forces in straits and chokepoints. Mahan’s focus on blockades combined with Vego’s theory for sea control in straits and chokepoints can guide United States interplanetary grand strategy as the United States, China, India, Russia, the European Union, and countless others shift their sights towards the final frontier.

Straits and Chokepoints

Vego asserts that sea control, in its simplest form, is the ability for a nation to use a given part of the sea and associated air (and space) across the spectrum of conflict to deny the same to the enemy.7 Applying Vego’s definition of sea control and its application to specific geographic regions, the importance of straits becomes evident. Straits or “chokepoints” are a textbook case of sea control limited to a specific region and have remained of great importance throughout history. Nations that control these chokepoints can asphyxiate the enemy by halting commerce causing major economic impacts or denying freedom of maneuver in wartime. During the Napoleonic War, the British had a vested interested in ensuring a neutral Denmark and thus neutral Danish Straits. The plains to the north provided timber for the British and French Navy and were also critical for transporting grain amongst other vital commerce. A century later, Germany’s de facto control of the Danish Straits prevented Britain from reinforcing its Russian ally during the First World War. During the Second World War, the occupation of Denmark allowed Germany to leverage the full economic resources of Scandinavian countries while denying the Royal Navy access to the Baltics.8 Even in a galaxy far, far away the Trade Federation realized the importance of blockading Naboo by placing their battleships in key locations with the goal to leverage the full economic resources of the planet.

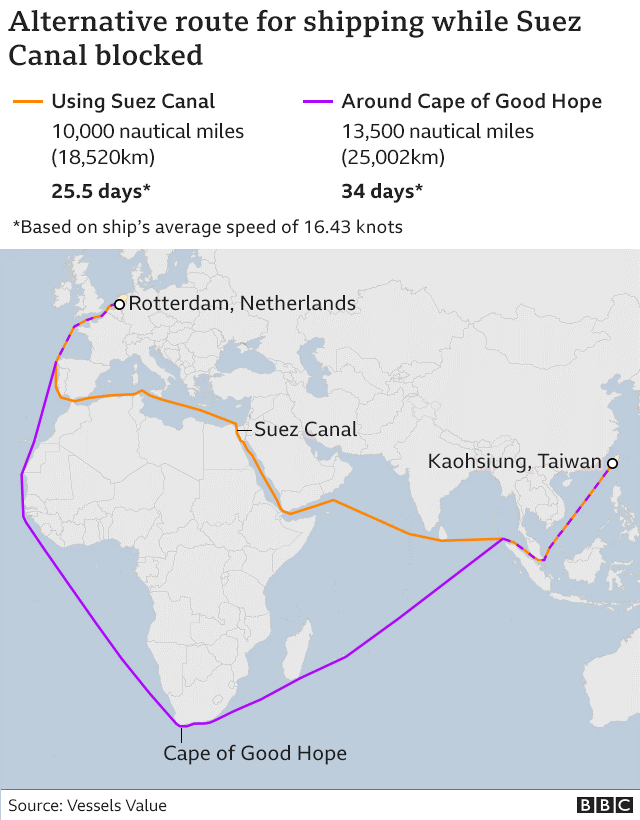

Admiral John Fisher, the First Sea Lord of the Royal Navy and founding father of the Dreadnought battleship, identified the strategic importance of Straits when positing this rhetorical question, “Do you know that there are five keys to the world? The Strait of Dover, the Straits of Gibraltar, the Suez Canal, the Straits of Malacca, the Cape of Good Hope. And every one of these keys we hold.”9,10 Although oversimplified, his aphorism still rings true today. In March of 2021, the M/V Ever Given became lodged in the Suez Canal disrupting commerce and causing an estimated 9.6 billion dollars of economic damage per day.11 Ships once waiting in line to transit the Suez Canal extended their voyage and incurred additional fuel and crew costs by sailing around the Cape of Good Hope to their destinations.12,13

Fig. 1. Ships sailing around the Cape of Good while the Suez Canal was blocked in March incurring extra fuel, time, and crew costs. (BBC graphic)

Lagrange Points and Halo Orbits

The same analogy holds true for space travel. Despite the incomprehensible distance, times, and vastness required for interplanetary travel, the chokepoints of sea control can also be distilled down to Lagrange points for space control.14 Lagrange points are specific points (orbits) between any two orbiting celestial bodies where gravitational and centrifugal force negate each other, resulting in orbits that can be maintained with little to no propulsion.15 In simpler terms, only five Lagrange points (labeled L1 through L5) exist between planets and their respective moons or the Sun and its planets.16 Due to the gravity-stable properties and low fuel requirements of Lagrange points, they are ideal for satellites and are understandably well known by space agencies. In 2017, the Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, Dr. Jim Green, proposed the radical idea of placing a magnetic dipole shield at Lagrange point L1 in the Sun-Mars system to create an artificial magnetosphere, shielding Mars from solar winds and radiation. This shield would allow the volcanic activity on Mars to continually build up the atmosphere until a point of self-sustainment.17 If a state or non-state actor saturates or even blockades critical Lagrange chokepoints, the ramifications could range from economic depression and collapse of critical space infrastructure to the loss of interplanetary colonies that may eventually inhabit the cosmos.18

Closer to home, satellites from both NASA and the European Space Agency have already made home in earth-system Lagrange points. Lagrange points, specifically L1, L2, and L3, can also host an ecosystem of satellites through halo orbits.19 Although halo orbits are dynamically unstable and require more fuel than the stable Lagrange points at L4 and L5, satellites in halo orbits at L2 can serve as communication relays from the dark side of the moon, Mars, and other celestial bodies. In May of 2018, China placed the first-ever lunar relay satellite, Queqiao, into a halo orbit at the Earth-Moon L2. The following year, China landed their Chang’e 4 rover on the far side of the moon using Queqiao as a communication relay.20 In addition to China, NASA and the European Space Agency have already placed satellites in Lagrange point L2 while countries such as Russia, India, and Japan have their own Lagrangian aspirations.21 Because Lagrange points and associated halo orbits can only host a limited number of spacecraft, the contest for this limited real estate by spacefaring nations can have terrestrial consequences.22,23 These important areas in space are not treatise to international norms and measures yet will be essential for lunar and interplanetary space lines of communication.24

Fig. 2. The Five Lagrange points, L1 through L5. M1 represents the larger celestial body and M2 represents any celestial body whose orbit is anchored to it. If M1 represents the sun, M2 represents the planets. If M1 represents the planets, M2 represents its moons. Source: http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/Mechanics/lagpt.html

Access to Resources

The Trade Federation blockaded Naboo in an attempt to leverage the rare economic resources found in the planet. Similar to here on Earth, access to resources is necessary to lift countries and their populations’ standard of living. It is unlikely that much of the world will sacrifice their consumerism to live in harmony with each other and Mother Nature, leaving the limited resources on Earth to support an ever-growing consumer economy. Governments in the future are likely to look to space to solve their growth problems, much as European colonization looked to supplement sapped domestic resources in the 17th and 18th centuries. Beyond Lagrange chokepoints serving as potential flashpoints for real-estate between countries launching satellites, Martian trojan asteroids make home in the gravity-stable environment at Lagrange points L4 and L5 in the Mars-Sun system.25 The imperative of space lines of communication is not necessarily scientific exploration or protection of desirable orbits, but the ability to leverage the vast resources that abound in space. One asteroid floating between Mars and Jupiter is assessed to contain over 10 quintillion dollars of precious metals, more than 10,000 times larger than the 2019 global economy, far more wealth than Han Solo could have ever imagined.26,27

Interplanetary Transport Network and Space lines of Communication

Alfred Thayer Mahan’s unmistakable first lines in the Influence of History Upon Sea Power state:

“The first and most obvious light in which the sea presents itself from the political and social point of view is that of a great highway; or better, perhaps, of a wide common, over which men may pass in all directions, but on which some well-worn paths show that controlling reasons have led them to choose certain lines of travel rather than others. These lines of travel are called trade routes; and the reasons which have determined them are to be sought in the history of the world.”28

While the great highway, wide common, and well-worn paths refer to the sea, his quote can be analogous to Star Wars as well. The hyperspace routes in Star Wars, or trade routes, link the major worlds in the galaxy like an intergalactic superhighway. The routes are safe and account for traveling without colliding into celestial bodies including their gravitational pull. Han Solo couldn’t just punch it when blockade running from Imperial Cruisers. As the Imperial Cruisers closed on him, he quipped to a young Luke Skywalker that, “Traveling through hyperspace ain’t like dusting crops, boy! Without precise calculations we could fly right through a star or bounce too close to a supernova and that’d end your trip real quick, wouldn’t it?”29

Fig. 3. Punch it! Still from “Star Wars: Episode V”. Copyright Lucasfilm Limited. Used under the terms of Fair Use per 17 U.S. Code § 107.

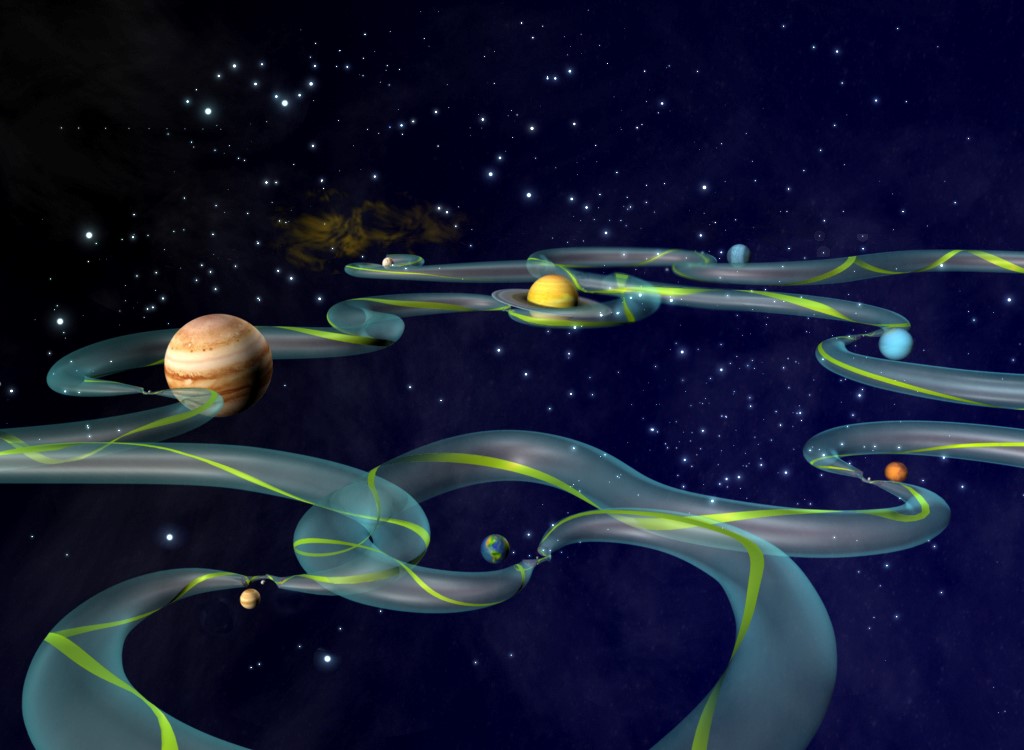

Although hyperspace only remains a reality in the Star Wars Universe, a great highway through our solar system already exists. Lagrange points serve as interplanetary straits, connecting celestial bodies in our solar system through the Interplanetary Transport Network (ITN).30 The halo orbits around Lagrange points can be used to alter spacecraft and satellite trajectories to arrive at any point in the solar system with minimal energy, although reaching Mars could take a millennium using the ITN – far longer than the record breaking 12 parsec Kessel Run flown by Han Solo in the Millennium Falcon.31,32 However, the slowness of ITN trajectories can be modified with external speed injections. In 2003, Cal-Teach professors introduced a Multi-Moon Orbiter concept.33 The concept proposed that a spacecraft could use Lagrange points to modify its trajectory to survey the moons of Jupiter with a final touch down on Europa where NASA speculates both water and life could exist.34 Lagrange points will serve as the keys to unlock the universe that could transform mankind into a multi-planetary species.

Fig. 4. Artist’s depiction of the ITN that connects our solar system. Abrupt changes in trajectory are due to Lagrange points. Image credit: NASA/JPL

The Line between Prescient and Far-fetched

While critics may point to the astronomical costs and technological gaps that make interplanetary travel an impossibility, the critique is confined to now. In 1945, some mainstream scientists felt that satellites and intercontinental ballistic missiles were fool hardy errands that would be too technologically complex and cost prohibitive to develop.35 Less than twelve years later, Sputnik orbited the planet and within fifteen years, intercontinental missiles rested in silos. The once lone small metal ball named Sputnik launched by the Russians in 1957 has given way to a world that depends on complex networks of satellites. While GPS has become a household name in a few short decades, Russia’s GLONASS, China’s Beidou, and Europe’s Galileo systems offer competing location services with global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) receivers. The recent out-of-control Chinese rocket shows that China’s Communist Party is serious about becoming a space-based power and willing to pursue this capability at all costs without due regard for safety.36 Even more recently, the Chinese landed their Zhurong rover on Mars where President Xi Jinping proudly praised all involved by saying, “You were brave enough for the challenge, pursued excellence and placed our country in the advanced ranks of planetary exploration.”37 On July 11th, 2021, Richard Branson along with five other crewmates flew to space aboard the VSS Unity proving the viability of space tourism.38,39 The following week, Jeff Bezos and Blue Origin followed suit in achieving spaceflight in the New Shephard.40

The rapid pace of artificial intelligence (AI) advancement and Space X’s Falcon 9 rockets, Starhopper, and now Starship all show that a manned mission to Mars is a matter of when, not if, and might occur as soon as 2024. SpaceX has plans to colonize Mars with one million people by 2050.41,42

To sustain and develop a Martian colony and more, established and secure space lines of communication will be of critical importance. Interplanetary pursuits are being pursued at a break-neck pace by both allies and adversaries, including China, Russia, India, United Arab Emirates, the United Kingdom, and European Union.43 As each country pursues its own interests among the solar system, the United States must develop a grand strategy in the solar system to protect US interests against both state and non-state actors. The reflection of this reality came to fruition on June 7th, 2021, when Congressman Ted Lieu introduced the Space Infrastructure Act which will “issue guidance with respect to designating space systems, services, and technology as critical infrastructure.”44

Fig. 5. The success of Martian colonies will require an intelligent space strategy. Artist’s illustration of SpaceX Starships on Mars. Image credit: SpaceX.

Conclusion

The blockade of Naboo never happened, but it does have historical precedents and very real implications for space exploration and exploitation. As countries vie to expand their resources, they not only gaze across the vast oceans but upwards towards the final frontier. The increased focus on Mars and beyond demands a robust US interplanetary strategy to protect the United States’ interests in the cosmos. While the United States is rightly focused on earth-based priorities, Milan Vego’s canonical book Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice, can provide guidance for interplanetary strategy in ensuring a “a free and open [solar system] in which all nations, large and small, are secure in their sovereignty and able to pursue economic growth consistent with accepted international rules, norms, and principles of fair competition.”45 If the United States neglects interplanetary strategy, the United States will be left behind as other countries not only develop but execute their interplanetary strategies.46 If Admiral Fisher was alive today, he would ask, “Do you know that there are five keys to the solar system?” We need to ask ourselves, who will control these keys?

Lieutenant Commander Dylan “Joose” Phillips-Levine is a naval aviator and serves with TACRON-12. His Twitter handle is @JooseBoludo.

Lieutenant Commander Trevor Phillips-Levine is a naval aviator and serves as a department head in Strike Fighter Squadron Two. His Twitter handle is @TPLevine85.

Endnotes

1. George Lucas, 1999, ¨Star Wars: Episode I The Phantom Menace”, Lucasfilm Limited.

2. “Databank Naboo,” Star Wars, https://www.starwars.com/databank/naboo.

3. Tim Veekhoven, “The Trade Federation And Neimoidians: A History,” Star Wars (14 October 2014), https://www.starwars.com/news/the-trade-federation-and-neimoidians-a-history.

4. Erin Blakemore, “How the East India Company became the world’s most powerful business,” National Geographic, (6 September 2019) https://www.nationalgeographic.com/culture/article/british-east-india-trading-company-most-powerful-business.

5. Dr. Milan Vego, “Naval Classical Thinkers And Operational Art” Naval War College (2009) 3 Naval War College https://web.archive.org/web/20170131144505/https:/www.usnwc.edu/getattachment/85c80b3a-5665-42cd-9b1e-72c40d6d3153/NWC-1005-NAVAL-CLASSICAL-THINKERS-AND-OPERATIONAL-.aspx.

6. Dr. Milan Vego, Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice, Routledge; 1st edition, (14 April 2016), 189 https://www.amazon.com/Maritime-Strategy-Sea-Control-Practice-ebook/dp/B019H40ST2

7. Ibid, 24

8. Ibid 188

9. The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica, “John Arbuthnot Fisher, 1st Baron Fisher,” Encyclopaedia Britannica https://www.britannica.com/biography/John-Arbuthnot-Fisher-1st-Baron-Fisher.

10. Dr. Milan Vego, Maritime Strategy and Sea Control: Theory and Practice, Routledge; 1st edition, (14 April 2016), 188 https://www.amazon.com/Maritime-Strategy-Sea-Control-Practice-ebook/dp/B019H40ST2

11. Kshitij Bhargava, “Single ship stuck causing Suez Canal ‘traffic jam’ may cost $9.6 billion per day,” Financial Express (26 March 2021) https://www.financialexpress.com/economy/single-ship-stuck-causing-suez-canal-traffic-jam-may-cost-9-6-billion-per-day/2220575/.

12. Daniel Stone, “The Suez Canal blockage detoured ships through an area notorious for shipwrecks,” National Geographic (29 March 2021) https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/article/suez-blockage-detoured-ships-through-cape-good-hope-notorious-shipwrecks.

13. Peter S. Goodman and Stanley Reed, “With Suez Canal Blocked, Shippers Begin End Run Around a Trade Artery,” New York Times (26 March 2021, Update 29 March 2021) https://www.nytimes.com/2021/03/26/business/suez-canal-blocked-ship.html.

14. Lead Authors: Clementine G. Starling, Mark J. Massa, Lt Col Christopher P. Mulder, and Julia T. Siegel With a Foreword by Co-Chairs General James E. Cartwright, USMC (ret.) and Secretary Deborah Lee James in collaboration with: Raphael Piliero, Brett M. Williamson, Dor W. Brown IV, Ross Lott, Christopher J. MacArthur, Alexander Powell Hays, Christian Trotti, Olivia Popp, “The Future of Security in Space: A Thirty-Year US Strategy” Atlantic Council (April 2021) 35 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TheFutureofSecurityinSpace.pdf.

15. NASA/WMAP Science Team, “What is a Lagrange Point?,” NASA (27 March 2018) https://solarsystem.nasa.gov/resources/754/what-is-a-lagrange-point/.

16. Shane D. Ross, “The Interplanetary Transport Network,” American Scientist, Volume 94 (April 2006) 234 http://www.dept.aoe.vt.edu/~sdross/papers/AmericanScientist2006.pdf.

17.Matt Williams, “NASA proposes a magnetic shield to protect Mars’ atmosphere,” Universe Today (3 March 2017) https://phys.org/news/2017-03-nasa-magnetic-shield-mars-atmosphere.html.

18. Lead Authors: Clementine G. Starling, Mark J. Massa, Lt Col Christopher P. Mulder, and Julia T. Siegel with a Foreword by Co-Chairs General James E. Cartwright, USMC (ret.) and Secretary Deborah Lee James in collaboration with: Raphael Piliero, Brett M. Williamson, Dor W. Brown IV, Ross Lott, Christopher J. MacArthur, Alexander Powell Hays, Christian Trotti, Olivia Popp, “The Future of Security in Space: A Thirty-Year US Strategy” Atlantic Council (April 2021) 35 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TheFutureofSecurityinSpace.pdf.

19. Ibid 70.

20. Luyuan Xu, “How China’s lunar relay satellite arrived in its final orbit,” Planetary (15 June 2018) https://www.planetary.org/articles/20180615-queqiao-orbit-explainer

21. Lead Authors: Clementine G. Starling, Mark J. Massa, Lt Col Christopher P. Mulder, and Julia T. Siegel with a Foreword by Co-Chairs General James E. Cartwright, USMC (ret.) and Secretary Deborah Lee James in collaboration with: Raphael Piliero, Brett M. Williamson, Dor W. Brown IV, Ross Lott, Christopher J. MacArthur, Alexander Powell Hays, Christian Trotti, Olivia Popp, “The Future of Security in Space: A Thirty-Year US Strategy” Atlantic Council (April 2021) 35 https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/TheFutureofSecurityinSpace.pdf.

22. Ibid 70.

23. Ibid 10.

24. Ibid 72.

25. Jesse Emspak, Are Mars’ Trojan Asteroids Pieces of the Red Planet?,” Space (July 24, 2017) https://www.space.com/37565-mars-trojan-asteroids-pieces-of-the-planet.html.

26. Adam Smith, “Asteroid Worth $10 Quintillion Could Be Only One of Its Kind,” Independent (29 October 2020) https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/gadgets-and-tech/asteroid-10-quintillion-psyche-19-iron-nickel-b1419635.html.

27. “Star Wars IV: A New Hope Quotes,” Movie Quote Database, https://www.moviequotedb.com/movies/star-wars-episode-iv-a-new-hope/quote_29904.html.

28. Alfred Thayer Mahan, “The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783,” Dover Publications; Revised ed. edition (November 1, 1987) https://www.amazon.com/Influence-History-1660-1783-Military-Weapons/dp/0486255093.

29. “Star Wars IV: A New Hope Quotes,” Movie Quote Database, https://www.moviequotedb.com/movies/star-wars-episode-iv-a-new-hope/quote_29894.html.

30. Shane D. Ross, “The Interplanetary Transport Network,” American Scientist, Volume 94 (April 2006) 230 http://www.dept.aoe.vt.edu/~sdross/papers/AmericanScientist2006.pdf.

31. Ibid 236.

32. Kyle Hill, “How the Star Wars Kessel Run Turns Han Solo into a Time-Traveler,” Wired (12 February 2013) https://www.wired.com/2013/02/kessel-run-12-parsecs/.

33. Ross, S. D. and Koon, W. S. and Lo, M. W. and Marsden, J. E. “Design of a Multi-Moon Orbiter,” Spaceflight Mechanics 2003. Advances in the Astronautical Sciences. No. 114. American Astronautical Society, 1. https://resolver.caltech.edu/CaltechAUTHORS:20101007-131136558

34.“ Ingredients for Life?,” NASA https://europa.nasa.gov/why-europa/ingredients-for-life/

35. John. A. Olsen, “A History of Air Warfare,” Potomac Books Incorporated (2010), audiobook. Part 5 Chapter 16, time: 16:42.

36. Alison Rourke, “‘Out-of-control’ Chinese rocket falling to Earth could partially survive re-entry,” The Guardian (4 May 2021) https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/may/04/out-of-control-chinese-rocket-tumbling-to-earth.

37. Jonathan Amos, “China lands its Zhurong rover on Mars,” BBC (15 May 2021) https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-57122914.

38. Chelsea Gohd, “Virgin Galactic launches Richard Branson to space in 1st fully crewed flight of VSS Unity,” 12 July 2021) SPACE.COM https://www.space.com/virgin-galactic-unity-22-branson-flight-success

39. Mike Wall, “ Virgin Galactic Unveils New SpaceShipTwo Unity for Space Tourists,” Scientific American (23 February 2016) SPACE.COM https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/virgin-galactic-unveils-new-spaceshiptwo-unity-for-space-tourists/.

40. Paul Rincon, “Jeff Bezos launches to space aboard New Shepard rocket ship,” BBC (20 July 2021), BBC https://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-57849364

41. Hanneke Weitering, “Elon Musk says SpaceX’s 1st Starship trip to Mars could fly in 4 years,” Space (16 October 2020) https://www.space.com/spacex-starship-first-mars-trip-2024.

42. Morgan McFall-Johnsen and Dave Mosher “Elon Musk says he plans to send 1 million people to Mars by 2050 by launching 3 Starship rockets every day and creating ‘a lot of jobs’ on the red planet,” Business Insider (17 January 2020) https://www.businessinsider.com/elon-musk-plans-1-million-people-to-mars-by-2050-2020-1.

43. “Once a two-country race, Mars missions now on radar of multiple nations,” Times of India (18 February 2021) https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/home/science/once-a-two-country-race-mars-missions-now-on-radar-of-multiple-nations/articleshow/81096583.cms.

44. Mr. Lieu, “Space Infrastructure Act,” House of Representatives (17 May 2021) https://lieu.house.gov/sites/lieu.house.gov/files/LIEU_172_xml.pdf.

45. The Deparment Of Defense, “Indo-Pacific Strategy Report” Department of Defense (1 June 2019) https://media.defense.gov/2019/Jul/01/2002152311/-1/-1/1/DEPARTMENT-OF-DEFENSE-INDO-PACIFIC-STRATEGY-REPORT-2019.PDF.

46. Brien Flewelling, “Securing cislunar space: A vision for U.S. leadership,” Space News (9 November 2020) https://spacenews.com/op-ed-securing-cislunar-space-a-vision-for-u-s-leadership/.

Feature Image: Still from “Star Wars: Episode I” depicting the blockade of Naboo. Copyright Lucasfilm Limited. Used under the terms of Fair Use per 17 U.S. Code § 107.