This essay, is part of the Personal Theories of Powerseries, a joint Bridge-CIMSEC project which asked a group of national security professionals to provide their theory of power and its application. We hope this launches a long and insightful debate that may one day shape policy.

Air and land power leave monuments to teach us of their authority: from the House of Commons’ bomb-scorched archway to the nation-wide wreckage of the Syrian Civil War. Sea power’s traces are washed away by its namesake — no rubble marking the battle of USS Monitor vs. CSS Virginia nor shattered remains of the convoys from the Battle of the Atlantic. The power with which the sea consumes is the same power with which sea power is imbued. Sea power’s force, persistence, and fluidity –the vast opportunities afforded by the sea — create three properties: the gravitational, phantasmal, and kinetic manifestations of its power.

The Fundamental Nature of Sea Power

Sea power is the physical or influencing power projected by independent mobile platforms within a sea. Like the vast waters of the deep oceans, sea power does not “flow” from a source like air power would, nor does it need to “settle” as land power does. The sea is a large and open commons in which a platform can achieve mobile-and-independent semi-permanence. Being “mobile” gets to the core of sea power; it’s an ability to maneuver a semi-permanent threat at sea or anywhere near or touching the sea. Sea power provides a unique mid-point between persistence and mobility.

US Navy

Ordnance merely aimed or fired towards the sea is not sea power. Land-based aircraft dropping sea-mines is not sea power, just as naval gunnery on land targets is not land power, nor flying artillery shells air power. Land, sea, and air power can all be used to combat each other; their powers are not restricted to effects within or through their own medium. Our types of power are the spectrum of capability afforded by nature of one’s presence within a medium.

Sea Power’s Gravity: An Inescapable Weight

Adversarial resources are strongly drawn into defense against sea power’s mobility and potency; in this manner, sea power’s weight, or “gravity”, holds down adversarial actions. Even a weak fleet huddled in port can generate sea power, forcing the enemy to pull resources away from more productive tasks to hold down an adversary’s most mobile threat — it’s fleet.

Take the Spanish-American War, for instance. The Americans had an abiding fear of the mere existence of Spanish sea power and the possibility that it would descend without notice on their coastline, shelling cities and port facilities. Though the Spanish fleet was ultimately wasted in a force-on-force fight, strategists have historically referred to a standing fleet whose purpose is to leverage mere threat as “fleet in being”. Rather than winning through firepower, an in-port “fleet in being” has potent effect on even far-away nations by the potential of their sure potential.

Today it is easier to imagine a mobile “capability in being”, rather than a stationary “fleet in being”. This also leverages the advantages afforded by the sea. The might of this “capability in being” has been illustrated in the past by Allied sea power’s forcing the Nazi’s into building the failed “Atlantic Wall”.

In WWII, sea power afforded the Allies significant advantage, while the Reich’s land power was forced up against the coast to guard every inch of accessible shore of the Atlantic Wall. The Atlantic Wall stretched for hundreds of miles, covering every inch of Reich-held coastline. The scale of preparations and their drain on Nazi resources was enormous, but deemed necessary due to the threat of allied sea power’s mobile capability to penetrate of the continent.

The gravity weighs not only on an adversary’s defenses, but holds down an adversary’s desire to project power. Contrast the case of Taiwan to that of the South China Sea. American sea power has been a guarantor of unimpeded passage in the Pacific since the end of WWII. Taiwan’s existence reflects both the potential and the potency of American sea power, as was demonstrated in the 1996 crisis. However, China’s growing sea power creates space for it to unilaterally declare control of new areas in the South China Sea through ‘salami-slicing’, despite its neighbors’ protests.

Ultimately, sea power is tangible. Its destructive capability is only matched by its potential influence. Sufficient sea power, even hundreds of miles away, has enough gravity to hold down or absorb the resources of the mightiest land or air power. While the adversary of sea power must guard every crack in his armor, a sea power is at liberty to bide time and seek an asymmetry.

The Phantom of Sea Power: Pervasive Uncertainty

US Navy

Sea power’s gravity is complemented by the obfuscation and fluidity allowed by the sea. Armies leave a trail — they transit urban areas, gather supplies from the land, and generally reside where we do. The sea is far more secretive about its residents. Like silent undercurrents, sea power can be hidden from observers, summoning fearful phantoms.

The best modern example of the sea power phantom is the submarine at the 1916 Battle of Jutland. The mightiest fleet on earth could not bring itself to destroy the German fleet for fear of lurking U-boats. This example of sea-denial highlights a greater return than the expenditure of any ordnance.

Today, submarines have become greater tools for generating uncertainty. The submarine’s invisible presence places an adversary under threat of destruction by Tomahawk missile or direct action by inserted special operations forces. Further threat might be generated by the uncertainty of an un-located fleet or the aircraft that could come from anywhere deep enough for a carrier. Sea power has the unique ability to veil-and-move large amounts of force, leveraging fear of devastating capability hidden by the surface or the horizon.

Sea Power’s Kinetics: When Opportunity Knocks

The gravity and phantom of Sea Power is summoned by a credible threat. History speaks for sea power: the British Empire, the Napoleonic Wars, the Russo-Japanese War, Pearl Harbor, German unrestricted warfare, British logistics in WWII, island hopping, D-Day, and modern South China Sea bumper boats. In the interest of brevity, we will split sea power’s kinetic abilities into two categories: logistics and violence.

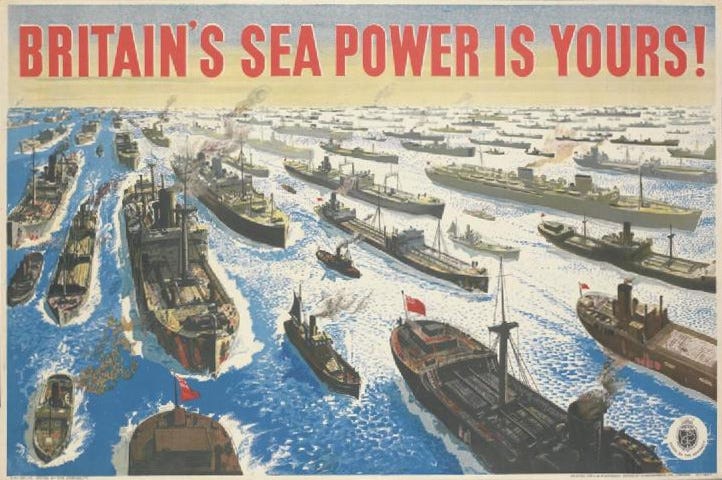

Sea Power’s logistical ability is often the forgotten part of sea power. A British WWI poster highlights this best. “Britain’s Sea Power is Yours” consists not only of a fleet of warships, but an entire horizon of commercial and military supply vessels. The ability to execute and secure seaborne logistics and to use and defend access to the global commons is potent power indeed. The effects of sea power on Malta, from its seizure by Britain during the Napoleonic Wars to its stubborn survival against the mightiest air force in Europe during WWII, serves as a testament to the subtle potency of the physical and logistical components of sea power. This flexible logistics train can either build an offensive opportunity or sustain a force until such opportunity arises.

The purely destructive capacity of sea power has indirectly already been described. Gravity becomes matter, the Allied fleet putting the wedge’s thin edge to the Atlantic Wall. The force feared by the Nazis came to fruition on D-Day. The phantom materializes, as experienced by Allied convoys facing wolf packs in WWII. It starts with the ability to find the point at which the thin end of the massive wedge can be applied; mobile forces deploying their feelers across the open commons. The American dance-and-smash across the Pacific is the best example, as Nimitz “island hopped” around Japanese defenses and two fleets fought for the first time without even seeing one another. Sea power allows forces a degree of sustainability of land forces to wait out an enemy while carrying along the independent payload with a degree of mobility of air power to respond in time to the development of that opportunity.

Sea Power: The Power of Opportunity

When we say “sea” we are using a placeholder for the large-and-open commons in which a platform can achieve mobile-and-independent semi-permanence. We discuss space power, but ships in space could eventually meld into a future sea power narrative. In WWI, one could argue that Zeppelins carrying aircraft could have joined a sea power concept. Rather than limiting oneself to the conventional “sea”, consider where humans have instinctively decided they can put “ships” from the type of freedom and opportunity the medium affords.

Sea power may have neither the total enduring strength of land power nor the mobility of air power — but it has a strategically potent degree of both. This affords it a unique gravity, an ability to generate fear, and a physical footprint unique from other powers. It finds, creates, and exploits opportunities better than any other type. It creates opportunity and suppresses those of adversaries by virtue of its physical capability or its influence upon enemy action. Sea power is the power of opportunity.

Matthew Hipple is an active duty officer in the United States Navy. He is the Director for Online Content at the Center for International Maritime Security, host of the Sea Control podcast, and a writer for USNI’s Proceedings, War on the Rocks, and other forums. While his opinions may not reflect those of the United States Navy, Department of Defense, or US Government, he wishes they did.