This post first appeared on the Small Wars Journal and is republished with permission. Read it in its original form here.

By Rick Chersicla

An American Infantryman, laden with equipment and weaponry, steps off the ramp of a specially modified landing craft. He is not storming the beaches of Normandy or moving ashore on Guadalcanal – in fact, he is not even landing from the open ocean or a sea. Instead, this is the scene of a member of the Mobile Riverine Force (MRF), a joint Army-Navy venture formed during the Vietnam War. In an often-overlooked part of the war, soldiers and sailors worked together in the Mekong Delta of South Vietnam to dominate the fluvial local terrain in the region—rivers, streams, and swampy rice paddies. Using World War II era equipment and creating tactics and techniques while under fire, the men of the MRF wrote the modern chapter on riverine warfare for the U.S. Army.

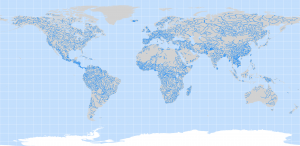

While preparing for riverine warfare is not a common task, it is not a new challenge for the U.S. Army. Since its inception, the Army has dealt with the tactical challenges caused by rivers – from New Orleans to Vicksburg, and from the Philippine Insurrection to the Rhine. Despite the fact that the Army’s experience with riverine warfare peaked with the MRF of the Vietnam War, the concept is not outdated.

This topic is relevant for modern strategists for the simple reason that while new technologies and global politics rapidly change and influence the way we fight war, terrain is an enduring aspect of war. Simply put, geography will continue to contribute to how the Army fights its wars. Furthermore, with the increasing focus on operations in littoral regions, riverine operations are a natural outgrowth from littoral concerns if the military is serious about projecting power. In this paper, I seek to explore what could be considered a capability gap in the field of riverine warfare. Using a case study of the MRF as an example, I hope to discern lessons learned in order to guide the possible formation and training of a future joint force similar to the MRF.

Origins of the Mobile Riverine Force

While the MRF was a joint Army-Navy venture, it was established on the bedrock of experience that the Navy had accumulated in South Vietnam. In 1959, naval advisors were approved to accompany the South Vietnamese Navy on operational missions, provided that they did not engage in actual combat. The primary focus of the naval advisors had been to build the interdiction capabilities of the South Vietnamese Navy along the coast. By 1961, as the number of advisors increased, the mission itself was expanded to include the task “patrol the inland waterways.” The early Naval advisors faced significant equipment challenges due to the lack of coastal or riverine crafts in the Navy’s inventory.

In addition to the dearth of equipment, there was a surprising lack of doctrine given the history of “brown water” warfare, as river fighting has occasionally been referred to. The Navy looked to the earlier experience of the French for inspiration. The French involvement in Southeast Asia provided a more immediate blueprint for the basis of American riverine operations in Vietnam. Between 1945 and 1954, the French developed river flotillas, the navales d’assault (naval assault divisions), better know as the Dinnassauts. Organized by the French Army for transportation and patrolling, the flotillas could support roughly a battalion-sized element. The Dinnassauts were comprised of a variety of types of landing craft, generally manned by the French Navy. The composition of the American MRF would mirror some aspects of the French organization, but more importantly, would seek to avoid some of the weaknesses of the French Dinnassauts.

The French Dinnassauts did not have a large landing force organically assigned to it, a point that was rectified by Military Assistance Command- Vietnam (MACV) planners for the United States. One of the strengths of the MRF was its joint relationship between the Army and the Navy – the Army units of the MRF did not rotate out to other commands or locations, as had happened during the French experience.

Similarly, the lack of organic infantry posed a challenge for the French with regards to the base defense for the Dinnassauts. The MRF would solve issue a decade later by rotating organic forces through security duty while conducting operations. When reflecting on their riverine experience in Vietnam, the French concluded that two of the key improvements that would have increased efficiency were increased armament, and the permanent joining of Army and Navy forces for riverine operations. These lessons learned would influence the formation of the riverine forces during the American experience in Vietnam, and directly contributed to the MRF’s joint nature and extensive firepower.

With the departure of the French, American military personnel stepped in to advise the military of South Vietnam. U.S. Naval advisors were the first Americans to operate in any appreciable number in the Mekong Delta, where the MRF would eventually conduct combat operations. The Navy gained experience operating in the rivers and off the coast of the Mekong Delta with Task Force 115 (code named MARKET TIME) and Task Force 116 (code named GAME WARDEN). The sailors of MARKET TIME had the key task of interdicting any infiltration attempts along the coast, while the GAME WARDEN sailors focused on interdicting enemy lines of communications along the Delta’s river ways. While there were both tactical and operational successes in both MARKET TIME and GAME WARDEN, the exclusively naval force did not have the ability to project combat power onto the riverbanks and shore line.

By 1966, General William Westmoreland began to see the importance of the Mekong Delta to the overall strategy of the Viet Cong. By this time, there was enough evidence that the Viet Cong sought to control the Delta’s Route 4 (the only real overland link between Saigon and the southernmost regions of the country) in addition to using the area to infiltrate supplies and manpower. The Mekong Delta was essentially the breadbasket of South Vietnam, providing the majority of the food and livestock for the rest of the country, and to lose control of the Delta would be a critical blow to the regime in Saigon.

While MARKET TIME and GAME WARDEN were disrupting the enemy’s logistics, it would take a significant number of ground forces to truly project combat power and clear the Viet Cong from the Mekong Delta. With the United States Marine Corps (USMC) elements in country fully committed to the northern portion of South Vietnam, the assault infantry element of the force would have to be provided by the United States Army. General Westmoreland accepted the proposal to create specialized units that could maximize the watery terrain of the Delta to seek out and destroy the Viet Cong, and the concept for the Mobile Riverine Force was born.

Much of the organization for what became known as the MRF sprang from a MACV study entitled Mekong Delta Mobile Afloat Force Concept and Requirements, published on 7 March 1966. While there would be some adjustments made to the initial recommendations, the key element articulated in the plan and later implemented was the utilization of naval ships for the basing of the MRF. Had the Army seized a portion of what little dry land was available in the Delta, it would have provided the Viet Cong with a propaganda coup in the heavily agricultural region – that the imperialist Americans were seizing the land of the farmers.

As a result, the base at Dong Tam, which would serve as the home base for the MRF, was created entirely by dredging sand from the My Tho River. In this way, the Army Corps of Engineers and Navy’s Seabees established a foothold from which the MRF could conduct operations in the Delta by literally creating one. This was an important departure from the French, whose riverine units had operated off of fixed land bases.

The Old Reliables Arrive

Providing the combat power of the MRF was the 2nd Brigade of the Army’s 9th Infantry Division. The 9th Infantry Division had been activated at Fort Riley, Kansas, on 9 February 1966, the only Army division specifically stood up for service in Vietnam. Colonel William Fulton, the commander of the 2nd Brigade, participated in what became to be known as the “Coronado Conference” in Coronado, California.

It was at the Coronado Conference that the leaders of each component of the soon to be joint venture, Captain Wade Wells for the Navy and Colonel Fulton, met to discuss the organization and command structure of the MRF. Neither Captain Wells or Colonel Fulton were named as overall commander of the MRF, instead, each officer would follow his own service’s command structure, with General Westmoreland himself being the first common command element. This unusual command relationship would prove to be surprisingly harmonious, with cooperation superseding service rivalries, and each element focusing on working together to accomplish the mission.

The MRF consisted of approximately 5,000 total sailors and soldiers. The Army compliment included the brigade headquarters, three infantry battalions, a field artillery battalion, and support troops, to include engineers. Due to the accumulation of surface water in the area of operations, elements of the MRF lobbied to increase the number of rifle companies per battalion from three to four, in order to allow the units to rotate their troops out of the Delta’s rice paddies. This change allowed for a drying-out period for those infantrymen who had been operating in the paddies inundated with water, without losing the operational tempo that was seen as a key to success by the senior leadership.

Naval ships served as the transportation and logistics element of the joint undertaking of the MRF. At its core, four World War II LSTs serve as barracks ships, equipped with helipads and modified for riverine operations. Additional means of support included a repair ship and an LST that could carry ammunition for 10 days of operations, and food for 30 days of operations.

These support elements as a whole were referred to as the Mobile Riverine Base (MRB), and were capable of moving up to 150 kilometers in a 24-hour period. Perhaps most importantly, elements could launch on day or night operations after only 30 minutes at anchor. The ability to move a force that was tailored to the environment such extreme distances and launch operations so quickly gave the joint force the reach needed to bring the fight to the Viet Cong in the Mekong Delta.

Several types of small craft provided the mobility and firepower components of the Navy’s contribution to the MRF, referred to by the Navy as River Assault Flotilla No. 1. The Armored Troop Carrier (ATC) was a modified LCM-6, a World War II era landing craft. The ATC had significant upgrades to the simple troop carrying variant of the 1940s, carrying twin 20mm guns, two .50-caliber machine guns, seven .30-caliber machine guns, and two 40-mm grenade launchers providing a significant punch in addition to its physical payload of up to 40 troops.

For situations that require even more firepower, the Monitor served in a “support by fire” capacity. The Monitors were essentially “the battleships of the force,” loaded with a 105-mm turret forward and an 81-mm naval mortar amidships, with .50-caliber and 20-mm guns on the aft portion of the craft. The last small craft that served a vital role with the MRF was the Assault Support Patrol Boat (ASPB), a radar equipped, double-hulled minesweeper. During movement, the assault support patrol boats provided reconnaissance and security to the force.

A striking shortfall of the formation and deployment of the MRF was the lack of dedicated riverine training. While Colonel Fulton had been relatively certain that his brigade would be designated as the brigade afloat for the MRF, the short period of time allotted for training led to a focus on counterinsurgency training. The training that the 2nd Brigade and the rest of the 9th Division underwent focused on lessons learned thus far by Army units in Vietnam, as well as current standard operating procedures for units already in combat. Additionally, Colonel Fulton felt that his brigade had to master “basic operational essentials” before moving on to the little-studied field of riverine operations. For some of the infantrymen of the 2nd Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division, their introduction to riverine training was their assignment to the USS Benewah upon arriving in the Delta.

While the bulk of the infantrymen in the 2nd Brigade did not receive riverine training, the brigade leadership and that of the subordinate battalions did participate in a ten-day course at the Naval Amphibious School in Coronado, California. While short in duration, the course (which had been set up at the request of Colonel Fulton) gave the Vietnam-bound command teams and their staffs the chance to focus exclusively on the challenge of riverine operations for the first time. This short course took place at the end of November 1966, and the bulk of the Coronado-trained officers arrived in Vietnam on 15 January 1967, serving as an advance party. Over the course of 31 January and 1 February 1967, the main body of the 2nd Brigade disembarked at Vting Tau in South Vietnam.

By late January 1967, efforts were underway for the men of the 2nd Brigade, 9th Infantry Division to receive riverine training “in-country.” The lack of time available for training at Fort Riley had prevented the unit from conducting a brigade-level training event in riverine operations, so a dedicated effort was made to provide at least a ten-day period of training. The 3rd Battalion, 47th Infantry Regiment however, was only able to complete three days or the requisite training before enemy actions resulted in the assignment of a mission in the Rung Sat special zone. The resulting mission was referred to as RIVER RAIDER 1, and was the first joint operation by U.S. Army and U.S. Navy units that would constitute the MRF.

As a result of the lack of dedicated riverine training and the dearth of accepted riverine doctrine (or at least joint doctrine), innovation played a key role in the operations of the MRF. To support medical evacuation and resupply efforts, another form of technology was needed to compliment the river-borne units. The soldiers and sailors of the MRF created what the brigade commander referred to as an “aircraft carrier (light)” when a helideck was added to an armored troop carrier.

This practice spread, and most of the armored troop carriers eventually sported a one-ship landing zone that could support a light observation helicopter. The men of the MRF also had to innovate when it came to employing indirect fire assets. The original plan called for separate barges to carry an artillery piece, and the prime mover (truck) required to tow it off the barge, up the riverbank, and into a firing position. When operations began, however, it became evident that not only were most of the banks of the rivers too steep and slippery for this practice to be put into effect, but that there was a lack of dry firing points other than the scant number of roads.

The 3rd Battalion, 34th Field Artillery Battalion experimented with the Navy and eventually called for six riverine artillery barges to be built in Cam Ranh Bay and sent to the MRF. The final product could carry two 105-mm howitzers and troop housing as well as up to 1,500 rounds for the howitzers, with the LCM-8 that towed the barge carrying additional ammunition. These artillery barges would travel at night and anchor offshore to supply close-in artillery support during operations. Colonel Fulton, the senior Army officer in the MRF, believed that the “floating” field artillery riverine battalion was the single greatest contribution to riverine warfare by the MRF.

The presence of the MRF is credited with turning the tide of the war in the northern Mekong Delta in the favor of the United States and South Vietnam during 1967 and 1968. Until 1967, enemy Main Force and Viet Cong units had moved virtually unhindered through the Dong Tam area. The enemy’s freedom of maneuver was greatly reduced, two Viet Cong battalions were pushed from the more populated areas, and the overall security in the city of My Tho was improved.

Most importantly, with Viet Cong effectiveness reduced, Highway 4 was reopened in 1967 and produce from the agricultural heart of Vietnam was able to flow to market along the Delta’s main ground route, for both domestic use and export. Overall, the MRF contributed to the overall counterinsurgency effort of the United States by pursuing the Viet Cong into what had long been uncontested sanctuaries, and supporting the local economy by the attrition of the Viet Cong who had closed down Highway 4. Colonel (later Major General) Fulton, credited the organization and mobility of the MRF for its success, writing that “the Mobile Riverine Force, because of its mobility, strength of numbers, and Army-Navy co-operation, was capable of sustained operations along a water line of communications that permitted a concentration of force against widely separate enemy base areas.

Post-Vietnam Operations

With the end of American involvement in the Vietnam War ended, interest from both the Army and Navy in riverine operations waned. The task of training in coastal riverine operations fell to Navy’s Coastal Riverine Squadrons (CRS) until 1978, when they shifted focus to exclusively support special operations. The Marines retained a small number of craft for riverine operations, but neither the boats nor the units were intended or capable of executing large unit operations.

Following the invasion of Iraq in 2003, there was a limited resurgence in riverine operations as first Marine and then Naval units conducted security patrols around dams and other key infrastructure. The Navy embraced the “brown water” concept in 2006 by establishing Riverine Group One (RIVGRU 1), which grew to become three Riverine Squadrons (RIVRONs). However, even this change was fleeting, and by 2012 the Riverine Groups had been consolidated with the Marine Expeditionary Security Squadrons (MISRONs), and reflagged as the Coastal Riverine Groups (CRG). One CRG is located on each coast of the United States, but with only one riverine company per squadron, the focus is overwhelmingly on maritime security.

While the CRGs conduct a variety of important missions, ranging from port defense and harbor security to small unit insertion/extraction and tactical intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance, they lack the power projection that was available to the MRF of the Vietnam era. The Mark VI Patrol Boat, the most recently acquired craft for the CRF, contains a bevy of advanced systems and weaponry, and will surely provide security to littoral areas. However, with a capacity to support only an eight-man team, the Mark VI provides more of a sharp jab than a knockout punch when it comes to force. Most importantly, the emphasis for both the Mark VI and the CRF that owns it is on coastal, not riverine operations.

Riverine Operations in the 21st Century

There are several reasons why riverine operations deserve more consideration by the Army. Simply put, joint operations can be a complicated affair, one in which “on the job training” can be costly in both lives and resources. As Lester Grau points out, the coordination and “commingling of forces” in a situation such as riverine operations would happen at a fairly low tactical level, among organizations that tend to have the least amount of experience with joint operations. A more detailed study of riverine operations in the context of the current operating environment could mitigate friction and prevent growing pains in the future.

A 2014 research paper from the Combined Joint Operations from the Sea Center of Excellence (CJOSCOE) identified capability gaps in NATO doctrine related to riverine operations. While the paper was commissioned at the request of the French, its authors believe that the trends identified within it could be useful to other countries as well. The most relevant finding to any future U.S. joint riverine force is the conclusion that these types of organizations work best when they are joint.

A joint force, unified under a single commander, would allow that commander to extend influence beyond the riverine environment itself. For example, while a purely naval force would be limited to the rivers themselves, a force that included a conventional infantry platoon or company could be disembarked to move overland or transported up minor waterways and strike at enemy locations. This finding is concurrent with the success the MRF enjoyed as a true joint organization.

Riverine operations in the 21st century may not always be as simple as an infantry squad in a small craft conducting security patrols near a dam. Rivers could provide the mobility for a unit to interdict enemy lines of communication, patrol unit boundaries and move supplies, in addition to move larger strike forces as was seen with the MRF in Vietnam. With the wide array of security challenges facing the United States, there are multiple locations that could feasibly host operations comparable to those of the MRF between 1967-1969, from the Niger River in West Africa, to the Yellow River in China.

Riverine operations follows logically after the Navy’s newest planning consideration, that of littoral operations. Several of the largest maritime threats of the 21st century, including terrorism and piracy, occur in coastal areas as opposed to the open ocean. Accordingly, the Navy dedicated significant time and money into developing the appropriate capabilities to handle threats in shallow, littoral areas. The Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) has been lauded as the answer to these shallow water threats, possessing the ability to move quickly and with more agility than larger craft. The LCS in many ways has replaced the frigates that have historically operated along coastlines.

The recent Sealift Emergency Deployment Readiness Exercise (SEDRE) conduct in April 2016 by a brigade from the Army’s 101st Airborne Division gives further credence to the argument for this capability. The first SEDRE conducted since the Global War on Terror (GWOT) began over fifteen years ago, it challenged the Army elements involved, as they have not been common practice. The Army brigade worked with the Navy’s Military Sealift Command to load and unload almost 900 pieces of equipment. This SEDRE demonstrates that the Army and the Navy have given at least some thought to larger scale joint operations, and as the lessons learned from this SEDRE are disseminated, more serious thought can be given to developing a MRB concept for the 21st century.

While the Navy has had the prescience to move away from strictly “blue water,” open ocean warfare and expand its field of view with regards to future threats, it is not enough. The focus on littorals, as evidenced by the development of the LCS, is only half of the equation. To be truly effective, the United States has to be able to project power everywhere, and the LCS is too big to navigate most rivers. A modern riverine force would be the logical extension of this littoral focus, and the answer to this problem should mirror many aspects of the Vietnam-era MRF. The LCS fleet being fielded by the Navy could probably serve in a role similar to the MRB of the Mekong Delta. The key is fielding an element that can move platoon and company sized formation, with the option of massing an even conducting battalion sized riverine operations. If this theoretical next step was taken, the biggest challenges would be finding the most appropriate modern craft to recreate the role of the ATCs and Monitors of the MRF.

Hardware Challenges

The focus on larger ships for littoral operations, and the trend of riverine operations being within the domain of Special Operations Forces (SOF), means that one of the largest gaps for potential riverine operations is in existing U.S. Naval hardware. There are several possible contenders for the type of craft that could comprise the fleet of a future MRF. The current workhorse the United States Marine Corps should be a logical option, but the venerable Marine AAV-7 is too small and provides too little by way of firepower to serve as a new ATC. The AAV-7 carries 21 combat loaded Marines, and is armed with a .50 caliber machine gun and 40-mm grenade launcher. While it is tracked, which means it can move from water to land seamlessly, it would not meet the necessary requirements. What a modern MRF would need is something closer to the ATC of the late 1960s, a craft that carry closer to 40 troops and boast a more formidable armament.

The Royal Navy of the United Kingdom has two variants of landing craft that could serve as a good example upon which to improve. The LCVP MK5 can carry thirty-five fully equipped commandos (or vehicles and equipment), and their Landing Craft Utility Mk10 can carry up to 120 fully laden commandos. While these two options are improvements over the AAV-7, they both still lack firepower. Additionally, none of these craft boast the helipads the ATCs of the MRF came to employ.

The most likely course of action would have to be a dedicated effort to either build specific craft for platoon and company size riverine operations in the 21st century, or to significantly modify existing watercraft. The British LCVP MK5 is not very different than the existing American LCUs, but they both lack the protection and firepower to fulfill the role of an ATC. The modifications made to the LCUs of the 1960s that resulted in the ATCs were the results of lessons learned from the French and early American river operations. They key to successful riverine operations in the 21st century is the design and adoption of these boats now, so doctrine and tactics can be developed before the threats are ready.

In addition to protection and firepower concerns, a 21st century MRF would have several planning considerations that the Vietnam-era MRF did not. The modern military relies so heavily on tactical satellite (TACSAT) and other advanced communications that there would be a significant increase in the amount of electronics aboard the river craft. Additional steps would probably have to be taken to water proof and safeguard our current systems.

The increase in the use of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) over the past two decades has changed, and continues to change, the face of war. To be relevant, any modern MRF would have to incorporate drone and possibly counter drone measures into operations. Another key different between 2016 and 1967 is the weight and size of the aircraft being used for medical evacuation (MEDEVAC) purposes. The UH-60, the current primary MEDEVAC helicopter, is significantly larger and heavier than the Vietnam-era UH-1s, a consideration that would impact the design and practicality of an onboard landing zone.

Training Recommendations and Conclusions

There are ways to explore this operational concept in a budget-constrained environment. While simultaneously codifying doctrine, acquiring equipment and developing tactics, techniques and procedures would have to be refined before any form of modern MRF could be deployed. While the capability gap exists, acquiring funding for a new initiative or type of unit can be a herculean effort. To train on this task while not creating a large specialized unit in a resource-constrained environment, one solution could be the creation of an equipment set similar in concept to the European Activity Set.

The European Activity Set includes 12,000 pieces of equipment, including approximately 250 tanks, Bradley Fighting Vehicles (BFVs) and self-propelled howitzers. There are currently elements of the European Activity Set in Germany, Lithuania, Romania, and Bulgaria. Using that concept, units could rotate to a location, familiarize and train on the riverine craft as needed. An additional benefit to this model is that riverine training could be conducted by U.S. Army Reserve or National Guard units conducting Annual Training (AT), as well as Active Duty (AD) troops since none of them would normally own the requisite equipment. The naval component of this possible force could maintain the watercraft and become the repository of knowledge for the joint riverine concept.

Conclusion

While not advocating any modern gunboat diplomacy, the hard truth is that by not having the capability- the equipment, doctrine, training- the Army is providing an exploitable weakness to any potential enemies. In acknowledging that rivers are not “simply obstacles to be crossed,” but terrain that can be controlled, the argument for another look at riverine operations for the U.S. Army becomes more urgent. The U.S. faces a long list of global threats, from Violent Non-State Actors (VNSAs) to increasingly belligerent states seeking to become near-peer competitors such as China or a resurgent Russia. The U.S. must make hard choices in assessing threats and determining how to resource its national security objectives.

While the MRB was a necessity given the fluvial environment of the Delta, it also provided the MRF with mobility, and a semblance of security. The potential benefits of the ability to influence land operations while not appearing overbearing on the local population cannot be overstated. While that idea may run contrary to population-centric COIN, the lack of a physical footprint could be helpful for a mission set consisting of surgical strikes and raids, or for training missions in which the local population is very concerned with Western influence.

Using Nigeria as an example, an overt presence of larger American units could play into the narrative of the local Islamist group, Boko Haram. Operating from a new-generation MRB would be one way to circumvent the jihadist narrative, while still providing train and assist capabilities, or conducting more kinetic, joint operations. Regardless of any altruistic intentions, the U.S. assumes the moniker of “imperialist” in the eyes of those opposed to U.S. involvement the moment a boot touches foreign soil, and operating on rivers may provide an alternative narrative.

History has shown that riverine warfare is an enduring part of warfare, and an acquired skillset. Given both the history of its occurrence, and the possibility of littoral operations in the future, it would behoove the Army to look more closely at riverine operations and pursue in some capacity a joint riverine organization. The situation may arise that more than a rifle squad or SOF team is needed to effectively project power. If a strong, joint riverine element can be developed, the U.S. can bypass the traditional practice of building up a beachhead, and the “ship to shore” way of moving combat power can truly shift to one of power projection from the littoral, “upriver,” to population centers.

The views expressed in his articles are those of the author, and do not reflect the official policy or position of the United States Army, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

Rick Chersicla is an active duty Infantry Officer in the United States Army. He is currently pursuing a M.A. in Security Studies at Georgetown University.

End Notes

[1] The CJOSCOE study cited later in this paper defines fluvial in accordance with Joint Test Publication 3-06, describing the fluvial environment as terrain where “navigable waterways exist and roads do not, or where forces are required to use waterways, an effective program to control the waterways and/or indirect hostile movement becomes paramount.” This rarely used term is ideal when describing riverine operations.

[1] Lester W. Grau and Leroy W. Denniston, “When a River Runs Through It: Riverine Operations in Contemporary Conflict,” Infantry, July-September 2014, 31.

[1] Thomas J. Cutler, “Brown Water, Black Berets: Coastal and Riverine Warfare in Vietnam”,(Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), 19.

[1] Cutler, Brown Water, 21.

[1] Cutler, Brown Water, 24.

[1] Cutler, Brown Water, 44.

[1] Department of the Army, Major General William B. Fulton, Vietnam Studies: Riverine Operations, 1966-1969, (Government Printing Office: Washington, D.C., 1985), 10. MG Fulton, given his experience as the former Brigade Commander of the Army element in the MRF, has authored a comprehensive study of the formation and tactics of the MRF.

[1] Fulton, Vietnam Studies, 10.

[1] Ibid, 11

[1] Ibid, 11.

[1] Ibid, 16.

[1] Ibid, 24.

[1] Ibid, 24.

[1] Ibid, 24

Featured Image: A Patrol Boat Riverine (PBR) MkII conducts operations during the Vietnam War, 1968. (U.S. Army Transportation Museum)