In my previous entry on the U.S.-ROK naval strategy after the OPCON, I argued for a combined fleet whereby the U.S. and ROK Navies, together with the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (JMSDF), may share their unique resources and cultures to develop flexible responses against future threats by Kim Jŏng-ŭn. Since I have been getting mixed responses with regards to the viability of the aforementioned proposal, I felt compelled to flesh out this concept in a subsequent entry. Here, I will examine command unity and operational parity within the proposed combined fleet.

First, as Chuck Hill points out in his response to my prior entry, should the three navies coalesce to form a combined fleet, the issue of command unity may not be easily overcome because “[w]hile the South Korean and Japanese Navies might work together under a U.S. Commander, I don’t see the Japanese cooperating under a South Korean flag officer.” Indeed, given the mutual rancor over historical grievances, and the ongoing territorial row over Dokdo/Takeshima Island, both Japan and the ROK may be unwilling to entertain this this arrangement. However, this mutual rancor, if left unchecked, could potentially undermine coherent tactical and strategic responses against further acts of aggression by Kim Jŏng-ŭn. It is for this reason that Japan and the ROK should cooperate as allies if they truly desire peace in East Asia.

So how can the three countries successfully achieve command unity within the combined fleet? One solution would be for an American admiral to assume command of the fleet. However, while it is true that the ROKN and the JMSDF have participated in joint exercises under the aegis of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, this arrangement would stymie professional growth of both the ROKN and JMSDF admirals who lack professional expertise comparable to their American counterparts. In particular, given that ROKN admirals will assume wartime responsibility for their fleets after the 2015 OPCON transfer, such arrangement would be unhealthy for the ROKN because it would only lead to further dependence on the U.S. Navy.

Instead, a more viable solution, as Hill suggests, would be for the three navies to operate on a “regular rotation schedule…with the prospective commander serving as deputy for a time before assuming command.” This arrangement would somewhat alleviate the existing tension between the ROKN and JMSDF officers. Furthermore, the rotation schedule may serve as an opportunity for ROKN and JMSDF admirals to prove their mettle as seaworthy commanders.

One successful example that demonstrates the efficacy of the above proposal is the ROKN’s recent anti-piracy operational experience with the Combined Task Force (CTF) 151 in the Gulf of Aden from 2009 to the present. In 2011, ROKN SEALs successfully conducted a hostage rescue operation against Somali pirates. ROKN admirals also assumed command of the Task Force twice, in 2010 and 2012 respectively.[1] According to Terrence Roehrig, the ROKN’s recent anti-piracy operational experience has “provide[d] the ROK navy with valuable operational experience [in] preparation for North Korean actions, while also gaining from participating in and leading multilateral operations.”[2]

However, it should be noted that it is “unclear whether ROK counter-piracy operations [with CTF 151] had a significant deterrent effect and, if so, it [was] likely to be limited.”[3] While CTF 151 may provide a plausible model for command unity for the combined fleet concept, it does not fully address potential operational and logistical problems in the event of another armed conflict on the peninsula. Moreover, while frequent joint exercises and exchange programs have lessened operational and linguistic problems, so long as the ROKN continues to be overshadowed by the Army-centric culture and structure within the ROK Armed Forces, it cannot function effectively as a vital component of the U.S.-ROK-Japan alliance in deterring future aggression by Kim Jŏng-ŭn.

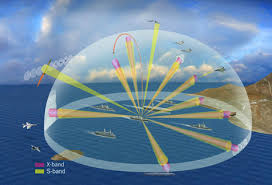

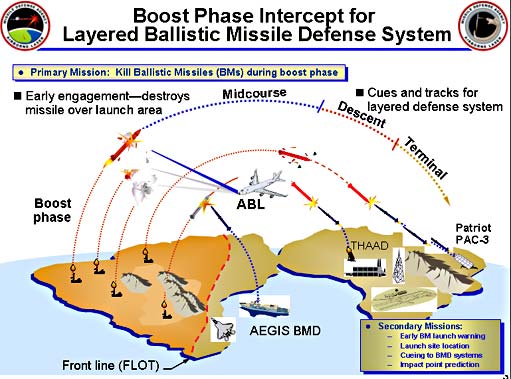

To achieve operational parity within the combined fleet, I recommend the following. First, the United States could help bolster the naval aviation capabilities of both navies. The JMSDF has been expanding its number of helicopter carriers, while the ROKN is expanding its fleet of Dokdo-class landing ships, supposedly capable of carrying an aviation squadron or unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), in addition to its naval air wing. However, the absence of carrier-based fighter-bomber capabilities may pose problems for the combined fleet concept because it deprives the fleet of flexible tools to respond expeditiously to emergent threats. Thus, the U.S. Navy and Marine Corps could equip the two navies with the existing F/A-18E/F Super Hornets or the new F-35s.

Second, both Japan and the ROK should bolster their amphibious and special operations forces (SOF) capabilities. As the successful hostage rescue operation in January, 2011, of the crew of the Korean chemical tanker Samho Jewelry by the ROKN SEAL team demonstrates, naval SOF capabilities may provide the combined fleet with a quick reaction force to deal with unforeseen contingencies. Furthermore, amphibious capabilities similar to the U.S. MAGTF (Marine Air-Ground Task Force) may provide both the ROK and Japan with the capabilities to proactively deter and not merely react to future DPRK provocations. That the Japanese Rangers[4] have recently trained for amphibious landing with U.S. Marines, while the ROK MND (Ministry of National Defense) has granted more autonomy to the ROK Marines, can be construed as steps in the right direction. As if to bear this out, there are reports that the ROK MND plans to establish a Marine aviation brigade by 2015 to enhance the ROKMC’s transport and strike capabilities.

In this blog entry, I examined command arrangement and operational parity to explore ways in which a combined U.S.-ROK-Japanese fleet may successfully deter potential DPRK threats. Certainly, my proposal does not purport to offer perfect solutions to the current crisis in the Korean peninsula. Nevertheless, it is a small step towards achieving a common goal—preserving peace and stability which all East Asian nations cherish.

Jeong Lee is a freelance international security blogger living in Pusan, South Korea and is also a Contributing Analyst for Wikistrat’s Asia-Pacific Desk. Lee’s writings have appeared on American Livewire, East Asia Forum, the Georgetown Journal of International Affairs, and the World Outline.

________________________________________

[1] Terrence Roehrig ‘s chapter in Scott Snyder and Terrence Roehrig et. al. Global Korea: South Korea’s Contributions to International Security. New York: Report for Council on Foreign Relations Press, October 2012, p. 35

[2] ibid., pp. 41

[3] ibid.

[4] Japan does not have its own Marine Corps.