He who defends everything defends nothing: The Philippines, Scarborough Shoal, the South China Sea, and Sabah and the Sultanate of Sulu

By Alex Calvo

Introduction. The Philippines’ South China Sea strategy brings together rearmament, rapprochement with the US, tighter security and defense links with Japan, and an international arbitration case under UNCLOS, whose fate is still pending, with oral hearings on jurisdiction having taken place over the summer. Manila’s narrative and legal arguments concerning Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal) are grounded on post-World War II developments. On 18 April 2012 the Philippines’ Department of Foreign Affairs stated that “The Philippines considers Bajo de Masinloc an integral part of Philippine territory on the basis of continuous, peaceful and exclusive exercise of effective occupation and effective jurisdiction over the shoal”, stressing this was not based on UNCLOS but “anchored on other principles of public international law”, and also underlining that it “is not premised on the cession by Spain of the Philippine archipelago to the United States under the Treaty of Paris”. While, alternatively, the Philippines may seek to resort to historical arguments from earlier eras, this may play into China’s hands, as noted by some observers. The offer to Malaysia to downgrade Filipino claims on Sabah in exchange for moves reinforcing Manila’s position in the international arbitration case under UNCLOS seems to confirm that the Philippines have indeed decided to focus on post-WWII arguments.

Alternatively, Manila may have sought to follow one of three routes to prove the past exercise of sovereign powers as the foundation for her territorial claims in the South China Sea. The first possible line of argument would involve proving that the Spratly were part of the Spanish Philippines, and were transferred to the US after the 1898 war. The second would be to claim that they were incorporated into the Philippines following their transfer to American sovereignty. Finally, a third approach would be to argue that they were part of the Sultanate of Sulu, thus linking the two claims.

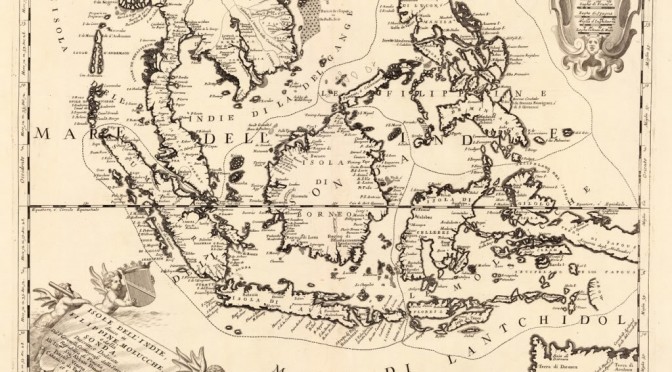

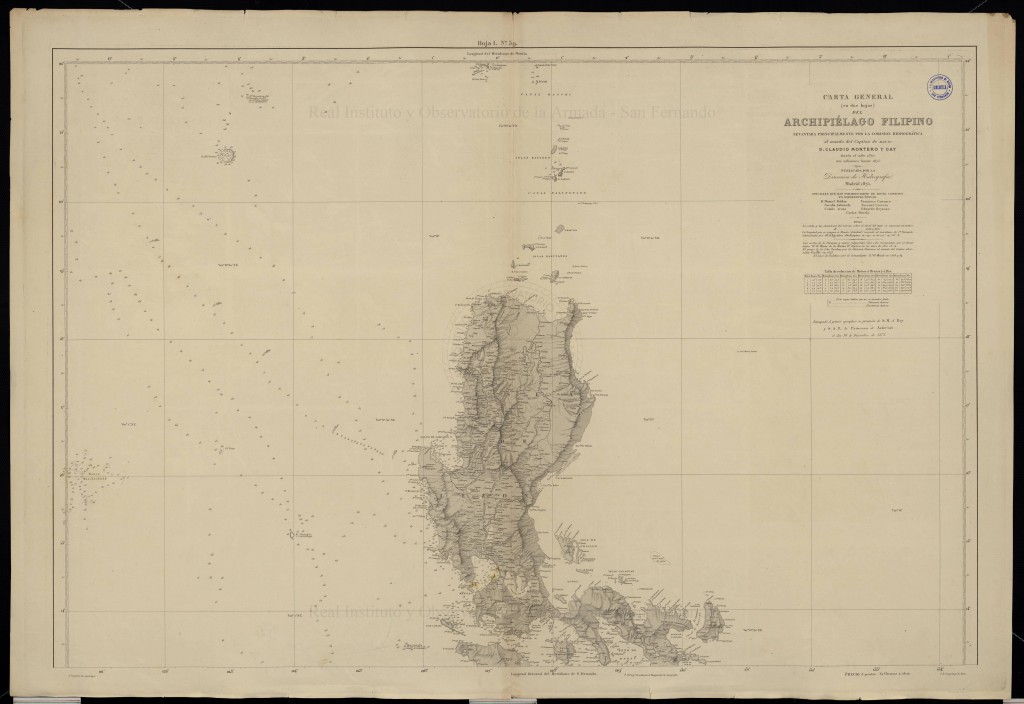

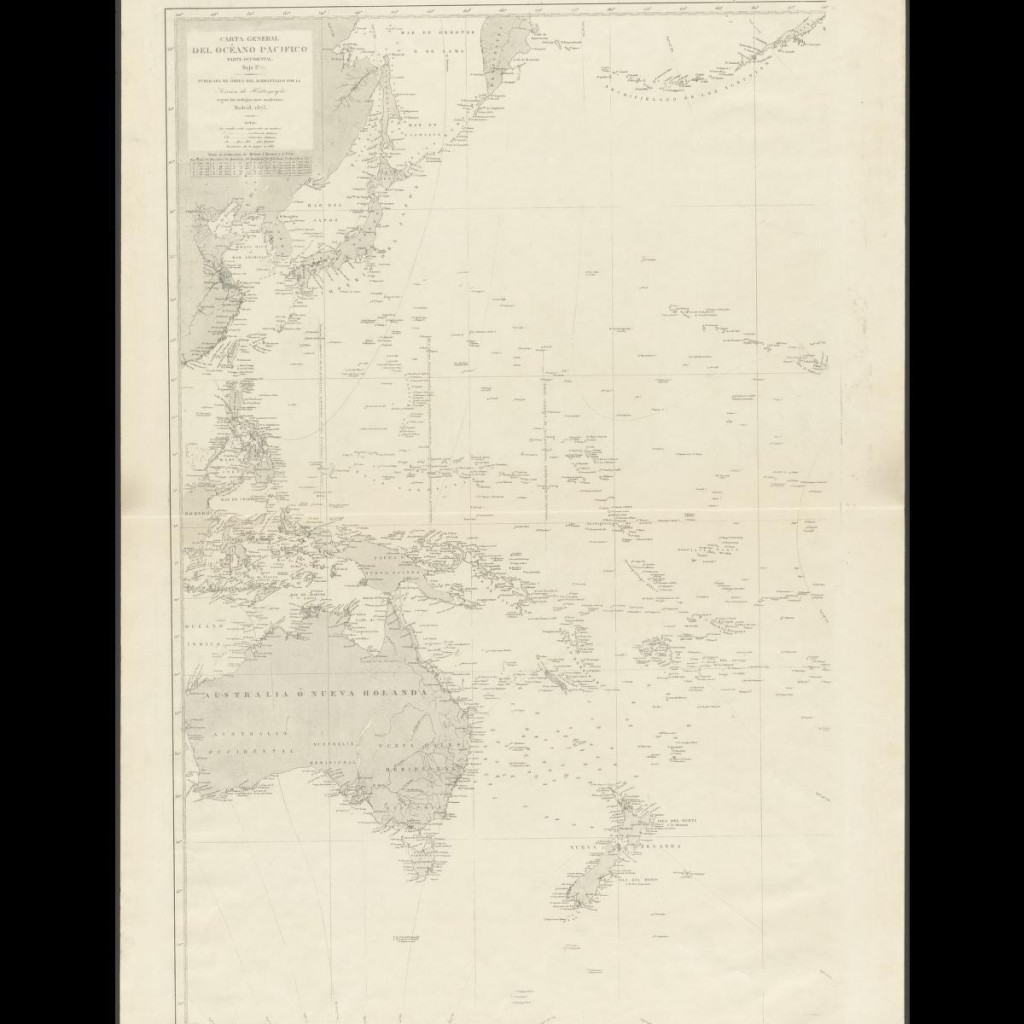

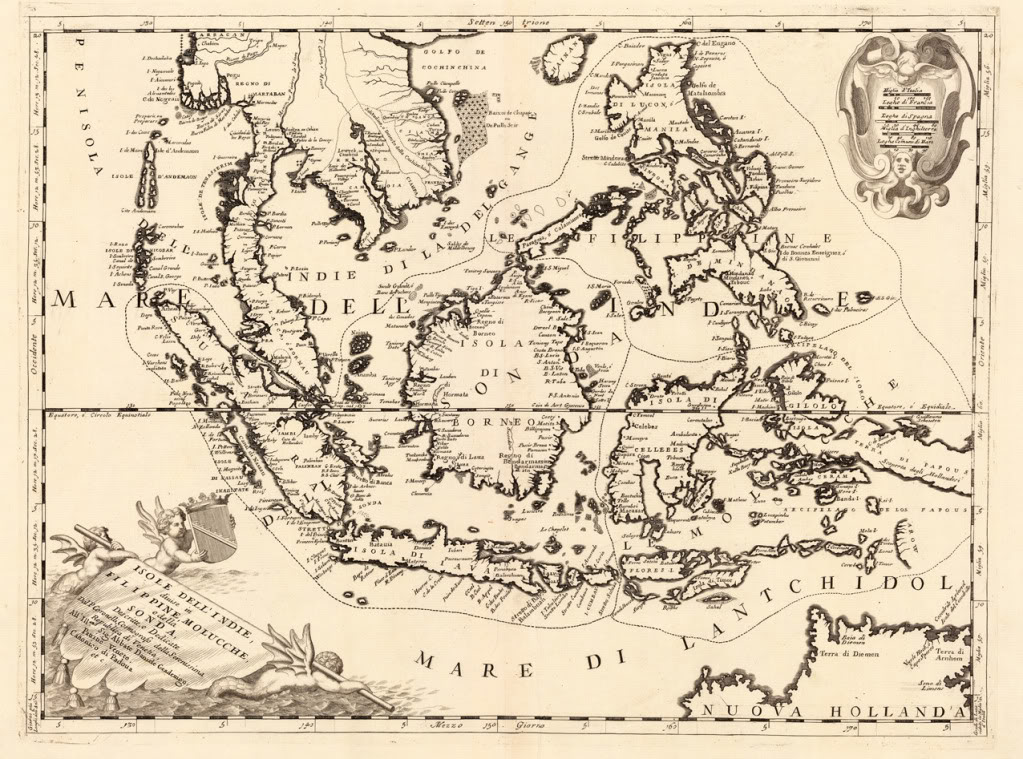

The Spanish colonial era. Three international conventions regulate the geographical extent of the territorial transfer following the 1898 war: the Treaties of Paris and Washington between the US and Spain, and that concluded between the United States and Great Britain on 2 January 1930. A range of potential problems would loom large if Manila tried to resort to the geographical extent of this territory. First of all, the mentioned treaties do not provide a fully detailed picture of the resulting borders. Second, the actual reach of the colonial administration was not always clear, with widespread resistance to Spanish rule and insurgency in a number of areas. In line with many other colonies, actual control was often a measure of distance from the capital, and went from long-standing exercise of sovereign powers, resulting in widespread cultural, linguistic, legal, economic, and social, influence, to little more than nominal sovereignty (or suzerainty when indirect rule was favored) on paper. Third, geographical knowledge was not always accurate, with some territories imperfectly mapped or chartered, and confusion sometimes arising out of conflicting accounts. Having said that, some maps, like the one below, do explicitly include features currently under dispute, such as Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal).

Furthermore, some expeditions and other activities took place featuring Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal). After a long history of uncertainty over its existence and location, the grounding of HMS Scarborough, chartered by the East India Company to transport tea, on 12 September 1748 led not only to its modern English-language name, but to its precise chartering. Navigation charts published after the incident reflected it, but uncertainty still meant some debate on exactly where the ship had run aground, and some decades would pass until this was dispelled. It was the Malaspina Expedition which in May 1792 finally ascertained the exact location of Scarborough Shoal, and confirmed that some reefs appearing on maps actually referred to this feature. This was followed, in 1800, by the first detailed Spanish survey, conducted by the frigate Santa Lucia, part of the Cavite-based naval squadron. Commanded by Captain Francisco Riquelme, she was one of the first steam-powered warships deployed in the Philippine Islands to take part in the campaigns against the Sultan of Sulu and the Moro slave-raiding pirate bands. Thus, this ship illustrates two aspects of Spanish colonial rule which to some extent are contradictory, supporting and weakening potential historical arguments in line with Philippine claims. On the one hand, it illustrates the connection between the Philippines and Scarborough Shoal, with activities from Luzon-based ships. On the other, it reflects how conflict with insurgents and pirates were a constant of the period, with sovereignty on paper extending further than on the ground (and the waters).

“This low-lying reef, per Riquelme, extends more than 8 2/3 miles from North to South, and 9 1/2 miles from East to West from one end to the middle part, but from there narrowing until it ends in a tip. It is surrounded by horrible dangers that may appear without warning or other markings to serve notice of their proximity. Some rocks can be seen slightly above water only by close observation on a clear day, and only by having careful look-outs can one see the reef at a distance of 7 miles”Capitan Riquelme’s findings were incorporated into the “Dorroteo del Archipielago Filipino”, the Spanish pilot’s guide. An 1879 edition reads:

Spanish colonial authorities did not only incorporate details of Scarborough Shoal into their charts, but also began to exercise search and rescue jurisdiction over the shoal, sending ships from Manila to assist vessels in distress. Since this is one of the activities traditionally considered to fall under the umbrella of exercise of sovereign powers, it is worth noting.

The Philippines under American sovereignty. A second possibility would be to argue that once under American sovereignty, currently disputed features clearly came to be officially considered part of Filipino territory. A significant obstacle to any such assertion is Washington’s long-held position that it takes no position on territorial disputes in the South China Sea, restricting its policy to how disputes are solved (insistence on peaceful solutions in accordance with international law) and the extent of any resulting settlement, with particular emphasis on freedom of navigation and overflight, and compliance with US views on the extent of coastal states powers in their EEZs. In December 2014 The Department of State published No 143 in its “Limits in the Seas” series, titled “China: Maritime Claims in the South China Sea”, which again emphasized that “The United States has repeatedly reaffirmed that it takes no position as to which country has sovereignty over the land features of the South China Sea”.

However, this view does not reflect the fact that the activities described earlier under Spanish colonial rule continued to take place after 1898. The most famous, and a well-documented, incident took place in 1913. A typhoon hit the S.S. Nippon, a Swedish steamer carrying copra, and she was wrecked on Scarborough shoal. This prompted Philippine authorities to intervene, together with private ships, in the rescue of the crew, investigate the accident, and carry out a scientific study on the effects of the sea on her cargo. In addition, the ship came under the salvage laws of the Philippines, and the resulting legal case was appealed all the way up to the Supreme Court of the Philippines, leaving behind an extensive paper trail documenting the exercise of a wide range of powers by the Philippine authorities in connection with Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal).

In the 1930s, the Commonwealth Government sought an explicit assertion of sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal, going beyond the exercise of administrative powers, including search and rescue. On December 6, 1937, Mr. Wayne Coy (Office of the US High Commissioner for the Philippines) asked Captain Thomas Maher (head of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey) whether any country had claimed Scarborough Shoal. The reply, dated 10 December 1937, was that no information was available on whether any nation had. Concerning the Santa Lucia 1800 survey, Captain Maher said “If this survey would confer title on Spain or be a recognition of sovereignty, or claim for same without protest, the reef would apparently be considered as part of Spanish territory the transfer of which would be governed by the treaty of November 7, 1900”. He also suggested that a new survey take place, and a navigational light be installed.

The next year saw Mr. Jorge B. Vargas (secretary to the president) write to Mr. Coy, asking about the status of Scarborough Shoal and saying that “The Commonwealth Government may desire to claim title thereto should there be no objection on the part of the United States Government to such action”. This prompted Mr Coy to forward this correspondence to the US War Department, which in turn sent them to the State Department, resulting in an interesting exchange. For example in a letter dated 27 July 1938 Secretary of State Cordell Hull told Secretary of War Harry Woodring that his department “has no information in regard to the ownership of the shoal”, which “appears outside the limits of the Philippine archipelago as described in Article III of the American-Spanish Treaty of Paris of December 10, 1898”. However, Hull wrote, “in the absence of a valid claim by any other government, the shoal should be regarded as included among the islands ceded to the United States by the American-Spanish treaty of November 7, 1900” and therefore the State Department would not object to the Commonwealth Government’s proposal to study the possible setting up of air and ocean navigation aids, as long as “the Navy Department and the Department of Commerce, which are interested in air and ocean navigation in the Far East, are informed and have expressed no objection”. The reply from Acting Secretary of the Navy W.R. Furlong to Acting Secretary of War Louis Johnson was positive, both concerning navigation aids and “the possibility of later claiming title”. The secretary of commerce also said his department had no objections.

We can observe a measure of ambiguity, though, with the US Government having no objections to the Commonwealth Government claiming Scarborough, and even considering it to be included in the second treaty with Spain following the 1898 War, but not actually claiming the features itself. Manila also expressed an interest in the Spratly, but despite this prompting Washington chose to keep a “low profile” concerning the archipelago, with non-recognition of claims by others and a close eye on Japanese interests and activities going hand in hand with a failure to officially claim the islands. The same applied could be said about Scarborough Shoal. In the words of François-Xavier Bonnet (IRASEC; Research Institute on Contemporary Southeast Asia), “the geographical proximity spoke in favor of the Philippines (rescue operations). In a way, Bajo de Masinloc could be seen as integrated in the sphere of influence of the Philippines, but outside the main archipelago. Political and symbolic acts, like naming the shoal, surveying, mapmaking, and organizing rescue operations, were the only appropriate activities that the Spanish and American authorities could do on an isolated shoal, which was, for the most part, underwater during high tide”.

The Sultanate of Sulu. A third possibility for Manila would be to claim sovereignty over Bajo de Masinloc as having historically been under the Sultanate of Sulu, that is merging the claim with that over Sabah. However the Philippines seem to be leaning towards focusing on Scarborough, going as far as offering Malysia to downgrade her claim to Sabah in exchange for support on the former conflict. This was clear in one of the Filipino moves this year connected to the international arbitration case, namely the offer to Malaysia, in a Note Verbale, to review its protest against the 6 May 2009 joint Vietnamese-Malaysian submission to the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS), containing a claim by Kuala Lampur of an extended continental shelf (350 nautical miles from the baselines) projected from Sabah. In exchange for this, Manila is requesting two actions that she believes would reinforce her case against China: First, to “confirm” that the Malay claim of an extended continental shelf is “entirely from the mainland coast of Malaysia, and not from any of the maritime features in the Spratly islands”. Second, to confirm that Malaysia “does not claim entitlement to maritime areas beyond 12 nautical miles from any of the maritime features in the Spratly islands it claims”.

The impact on Manila’s Sabah claims has not been lost on observers, with former Philippine permanent representative to the United Nations Lauro Baja Jr., if Malaysia explaining that if the deal is accepted the Philippines’ claim to Sabah will be “prejudiced”, adding that “We are in effect withdrawing our objection to Malaysia’s claim of ownership to Sabah”. Some voices argue that the Philippines need to stop claiming Sabah, since otherwise they are favoring Chinese claims to South China Sea features. William M. Esposo has criticized the “charlatans and overnight Sabah claim experts” who “thought they were patriots fighting for Philippine national interest” but “didn’t even realize that the arguments they were mouthing were supporting China’s very claims to our territory in the South China Sea”. Esposo cites Renato de Castro (De La Salle University International Studies Department), to stress that “historic claims, such as the one we have with Sabah, are the weakest cases when international courts decide territorial dispute”.

Conclusions. The Philippines are basing their South China Sea narrative on post-Second World War developments, and going as far as appearing ready to sacrifice their claim to Sabah in order to reinforce the arguments put forward in their international arbitration case against Beijing. This fits with Washington’s agnostic view of territorial claims, even when they involve areas formerly under US sovereignty. However, it is still interesting from a historical perspective to examine other possible arguments of this nature that could support Filipino claims on Bajo de Masinloc (Scarborough Shoal).

Alex Calvo is a guest professor at Nagoya University (Japan) focusing on security and defence policy, international law, and military history in the Indian-Pacific Ocean. Region. A member of the Center for International Maritime Security (CIMSEC) and Taiwan’s South China Sea Think-Tank, he is currently writing a book about Asia’s role and contribution to the Allied victory in the Great War. He tweets @Alex__Calvo and his work can be found here.