By Michael D. Armour, Ph.D.

Introduction

Recently there has been discussions at the highest level of the U.S. military concerning the deployment of U.S. Coast Guard assets to the South China sea and integrating them into the freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) conducted by the U.S. Navy relating to the manmade atolls constructed by the Chinese and subsequently claimed as Chinese sovereign territory. It may be that these U.S. Coast Guard units, if deployed to the area, may turn out to be a combat multiplier or a diplomatic plus. However, given the meager USCG budget and the limited assets of the service, their deployment may prove to be insignificant or even fraught with danger.

Chinese Territorial Expansion Claims

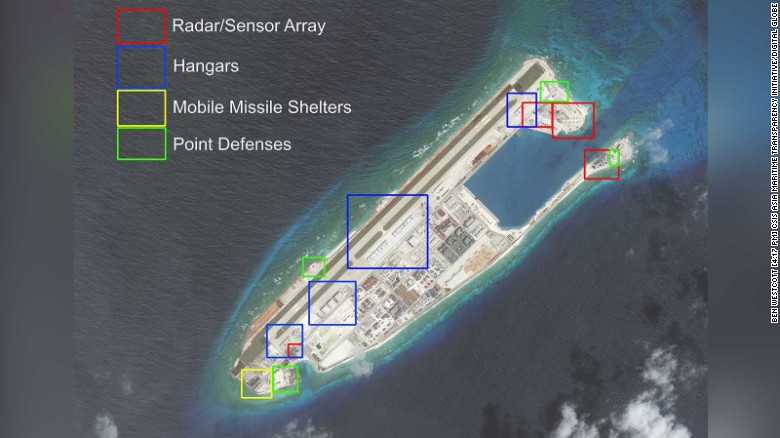

The South China Sea (SCS) has become a flashpoint on the world stage. The People’s Republic of China has asserted territorial claims for many islands in the Spratly and Parcel groups that other nations, such as Viet Nam and the Philippines, claim as their own sovereign territory. In addition to these claims, the Chinese have occupied and militarized many of the manmade atolls which they have constructed in the same area. The photo below of Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly chain illustrates the militarization of these artificial atoll platforms and the amount of military hardware that has been installed on many of them.1

Jeremy Bender reports that U.S. officials estimate that the Chinese construction at Fiery Cross Reef could accommodate an airstrip long enough for most of Beijing’s military aircraft and that China is also expanding manmade islands on Johnson South Reef, Johnson North Reef, Cuarteron Reef, and Gaven Reef around the Spratlys He goes on to say that China appears to be expanding and upgrading military and civilian infrastructures including radars, satellite communication equipment, antiaircraft and naval guns, helipads and docks on some of the manmade atolls. These would likely be used as launching points for aerial defense operations in support of Chinese naval vessels in the southern reaches of the SCS.2 Additionally, China considers the waters surrounding these islands to be sovereign territory requiring foreign vessel notification before approaching the 12-mile limit.

U.S. Opposition

An international tribunal in The Hague ruled against China’s behavior in the SCS, including its construction of artificial islands, and found that its expansive claim to sovereignty over the waters had no legal basis. The tribunal also stated that China had violated international law by causing “irreparable harm” to the marine environment.3 In relation to this the U. S. Navy has conducted freedom of navigation operations (FONOPS) around these atolls. On October 27, 2015, the guided missile destroyer USS Lassen transited within 12 nautical miles of Subi Reef, one of China’s artificially-built features in the SCS.4 On 10 May, 2016 the USS William P. Lawrence, a guided missile destroyer, sailed within 12 nautical miles of Fiery Cross Reef in the Spratly Islands.5 Also, in early 2016, USS Curtis Wilbur (DDG-54) came within 12 nautical miles of Triton Island in the Paracels without prior notification.6 According to Alex Lockie the Trump administration may be willing to continue these confrontational FONOPs which will surely heighten tensions in the area.7

Enter the China Coast Guard

The China Coast Guard (CCG) is a critical tool in the effort to secure China’s maritime interests. According to the U.S. Department of Defense, the enlargement and modernization of the China Coast Guard has improved China’s ability to enforce its maritime claims. In relation

to this, a survey conducted by China Power showed that of the 50 major incidents identified in the SCS, from 2010 onward, at least one CCG (or other Chinese maritime law enforcement) vessel was involved in 76 percent of incidents. Four additional incidents involved a Chinese naval vessel acting in a maritime law enforcement capacity, raising that number to 84 percent.8 China now possesses the world’s largest blue-water coast guard fleet and that it uses its law-enforcement cutters as an instrument of foreign policy.9 In relation to this, analysts conclude that in the flashpoints in the South China Sea, the Chinese are deploying coast guard ships and armed fishing vessels instead of its regular navy assets.10

Enter the U.S. Coast Guard (USCG)?

In January of 2017, Robbin Laird conducted an interview with the Commandant of the USCG, Admiral Paul Zukunft. He quoted the Admiral as stating the following in regard to the Coast Guard’s possible role in the SCS:

“I have discussed with the CNO (Chief of Naval Operations) the concept that we would create a permanent USCG presence in the South China Sea and related areas. This would allow us to expand our working relationship with Vietnam, the Philippines, and Japan. We can spearhead work with allies on freedom of navigation exercises as well.”11

The proposal to deploy USCG assets to the SCS was also espoused by David Barno and Nora Bensahel, who offered ways in which the United States could try to deter further Chinese encroachments in the SCS. One of their scenarios included the U.S. countering aggressive Chinese tactics by establishing a regular and visible Coast Guard presence in the area. They went on to say that:

“Only the United States has a major global coast guard capability, but some regional and even some international partners might be able to assist. As China has demonstrated, Coast Guard vessels are less provocative than warships, and their employment by the United States and partners could confront similar Chinese ships with far less risk of military escalation.”12

Others disagree with the above assessment. Brian Chao notes that the use of coast guard or constabulary forces in the South China Sea might actually increase the risk of war instead of easing tensions. He notes that using these forces as a diplomatic tool could lull all participants into a false sense of calm; however, these constabulary forces may be more willing to take aggressive actions because they may believe that the law is on their side.13

In addition to this negative stance, Aaron Picozzi and Lincoln Davidson question whether or not the U.S. Coast Guard could handle a mission in the South China Sea. They point out the reality that the U.S. Coast Guard lacks the capacity to base a “visible” presence in the SCS and that due to budget restraints, it simply does not have the ship capacity to carry out effective, sustained patrols in that area of operations. They also claim that the placement of U.S. Coast Guard cutters in the SCS would create a void in the service’s main mission, namely law enforcement, or search and rescue operations in home waters.14

If USCG assets are deployed to the SCS, it is hoped that because of the USCG’s good relations with its Chinese counterpart, tensions could be lessened and that U.S. interests could be better served. At this point, however, one must ask the following questions: What would happen if hostilities actually occurred and a situation arose pitting coast guard against coast guard? What kind of enemy capabilities and dangers would USCG personnel face?

The Capabilities, Structure, and Assets of the China Coast Guard

The China Coast Guard (CCG) was created in 2013 by the merging of five different organizations. These included the China Marine Surveillance (CMS); the Department of Agriculture’s China Fisheries Law Enforcement; the Ministry of Public Security’s Border Defense Coast Guard; and the Maritime Anti-Smuggling Police of the General Administration of Customs and the Ministry of Transport.15

The largest operational unit of the CCG is the flotilla, which is a regimental-level unit. Every coastal province has one to three Coast Guard flotillas and there are twenty CCG flotillas across the country.16 In 2015 the CCG possessed at least 79 ships displacing more than 1,000 tons, among which, at least 24 displace more than 3,000 tons. Most of these ships are not armed with deck guns but are equipped with advanced non-lethal weaponry, including water cannons and sirens.17 However, it seems that other CCG vessels are being armed with an array of more lethal weaponry. The China Daily Mail has reported that a number of CCG ships are being equipped with weapons which will give them greater strength to intensify law enforcement on the sea. The article also stated that China will transform many fishery administration and marine surveillance ships into armed coast guard cutters.18 The CCG has deployed a vessel (3901) that will carry 76mm rapid-fire guns, two auxiliary guns and two anti-aircraft machine guns. This monster ship, displacing 12,000 tons, is larger than U.S. Navy aegis-equipped surface combatants.

Jane’s 360 reported that images circulated on the Chinese internet indicate that the CCG has equipped its lead Type 818 vessel with the Type 630 30 mm close-in weapon system (CIWS).Two turrets of the system have been installed above the ship’s helicopter hangar, providing it with a means of defense against guided munitions and hostile aircraft. Information also indicates that the ship has also been armed with a 76 mm PJ-26 naval gun as its primary weapon.19

Lyle Goldstein relates that the Type 818 design discussed above can be rapidly configured into a naval combat frigate. He denotes the key characteristics for this class of ship, including, “134 meters in length, 15 meters at the beam, 3900 tons, and with a maximum speed of 27 knots. The ship is armed with a 76mm main gun, two heavy 30mm machine guns, four high pressure water cannons, and will also wield a Z-9 helicopter.”20

Enter the Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM)

In addition to their coast guard assets, the Chinese also deploy a vast number of fishing and merchant vessels that comprise what is referred to as the Chinese Maritime Militia (CMM). China has the largest fishing fleet in the world and it uses these assets as a third force in their effort to control the South China Sea. The CMM is a paramilitary force that operates in conjunction with the CCG but is cloaked behind the international legal shield of being civilian commercial assets.21 A 1978 report estimated that China’s maritime militia consisted of 750,000 personnel and 140,000 vessels and a 2010 defense white paper reported that China had 8 million militia units with the CMM being a smaller subset of that group.

The CMM personnel are trained in activities such as reconnaissance, harassment and blocking maneuvers, and this organization possesses the potential to evolve into a more formidable maritime fighting force. Militia ships could be armed with light anti-ship missiles such as the C-101 or HY1-A and be trained in more elaborate tactics such as maritime swarm tactics interconnected by Network Centric Warfare (NCW).22

Conclusion

It is entirely possible that the introduction of U.S. Coast Guard assets into the South China Sea area of operations will result in positive results in the form of increased capabilities and support off U.S. FONOPS and that USCG “white hulls” will relieve tensions in a conflicted milieu. However, there is also a possibility that USCG forces may become embroiled in actual conflict in the area; therefore, a comprehensive risk analysis should be undertaken before any considerable commitment is undertaken and the mission should be considered a “go” only if the benefits heavily outweigh the costs.

If the U.S. Coast Guard is faced with conflict in the South China Sea, it will not be alone in the effort. The full weight of the U.S. military will also be present. U.S. forces will be confronted with three levels of threat. These include the formidable Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy, the China Coast Guard, and the Chinese Maritime Militia. It is obvious that the main counter to these entities will be the U.S. Navy and the allied navies in the area. The assets that the U.S. Coast Guard could contribute to the effort would be limited and the cost might be considerable. While such a mission would enhance the Coast Guard’s image, it may turn out to be folly rather than strategy.

References

[1] https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2015/07/30/world/asia/what-china-has-been-building-in-the-south-china-sea.html

[2] http://www.businessinsider.com/china-is-fortifying-position-in-south-china-sea-2015-1

[3] https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/13/world/asia/south-china-sea-hague-ruling-philippines.html

[4] https://www.csis.org/analysis/us-asserts-freedom-navigation-south-china-sea

[5] https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/us-navy-carries-out-third-fonop-south-china-sea

[6] https://news.usni.org/2017/07/02/u-s-destroyer-conducts-freedom-navigation-operation-south-china-sea-past-chinese-island

[7] http://www.businessinsider.com/us-navy-freedom-of-navigation-south-china-sea-fonops-2017-2

[8] https://chinapower.csis.org/maritime-forces-destabilizing-asia/

[9] https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2015-04-0/chinas-second-navy

[10] https://chinadailymail.com/2017/06/17/china-marks-south-china-sea-claims-with-coast-guard-marine-militias/

[11] http://roilogolez.blogspot.com/2017/01/trump-kelly-us-coast-guard-in-south.html

[12] https://warontherocks.com/2016/06/a-guide-to-stepping-it-up-in-the-south-china-sea/

[13] http://nationalinterest.org/feature/coast-guards-could-accidently-spark-war-the-south-china-16766

[14] https://warontherocks.com/2016/06/can-the-u-s-coast-guard-take-on-the-south-china-sea/

[15] Martinson, Ryan D., “From Words to Actions: The Creation of the China Coast Guard” A paper for the China as a “Maritime Power” Conference July 28-29, 2015 CNA Conference Facility Arlington, Virginia, p.2.

[16] https://www.revolvy.com/main/index.php?s=China%20Coast%20Guard&item_type=topic

[17] Martinson, op cit, pp. 44-45.

[18] https://chinadailymail.com/2013/06/19/china-coast-guard-ships-now-carry-weapons-in-south-china-sea/

[19] http://nationalinterest.org/blog/the-buzz/chinas-new-coast-guard-vessels-are-designed-rapid-conversion-18221

[20 http://www.manilalivewire.com/2016/02/china-is-arming-its-coast-guard-ships-with-sophisticated-weaponry-reports/

[22] Kraska, James and Monti, Michael, The Law of Naval Warfare and China’s Maritime Militia, International Law Studies, Vol. 91, 2015.

[23] http://dailycaller.com/2016/09/24/how-the-us-should-respond-to-chinas-secret-weapon/

[24] Armour, Michael D., The Chinese Maritime Militia: A Perfect Swarm? Journal of Defense Studies, Vol. 10, No.3, July-September 2016, pp. 21-39.

Featured Image: U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Boutwell returns to homeport in San Diego after a 90-day counter drug patrol in the Eastern Pacific Ocean, Oct. 6, 2014. During the patrol, the Boutwell participated in six separate cocaine interdictions. (U.S. Coast Guard photo by Petty Officer 2nd Class Connie Terrell)