In Partnership for Peace (since 1994) and the NATO-Russia Council (since 2002), the Alliance reached out to Moscow, aiming to work closer together at sea. Positively, some of these opportunities turned into reality. NATO and Russia were working together in the Mediterranean (Med’) in Operation Active Endeavour to combat terrorism and in the Indian Ocean to combat piracy. Moreover, the planned, but cancelled joint naval mission to protect the destruction of Syria’s chemical weapons has shown the potential for increased cooperation. However, with the annexation of the Crimea, these opportunities ceased to exist.

Step up Black Sea Presence

Ukraine has no significant navy anymore. Instead, Ukraine’s warships were taken over by Russia, which makes Moscow’s navy, by numbers, larger than the US Navy. However, due to the warships’ poor quality, this increase in naval power does not present a game changer. Surely, a plus for Putin’s navy is that Sevastopol will remain a Russian naval base for decades.

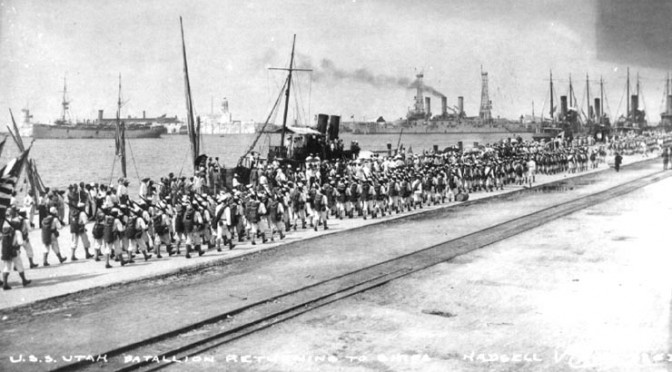

|

| Black Sea (Source: Wikipedia Commons) |

After Sevastopol is lost, Ukraine’s only significant port left is Odessa. NATO’s response should be to support Ukraine in keeping at least a small navy. Moreover, NATO should give a guarantee that, in case of further Russian aggression, Ukrainian ships can find shelter in Romania, Bulgaria, Turkey or Greece. In addition, SNMGs and SNMCMGs should pay regular visits to Odessa; on the one hand for partnership with Ukraine and on the other hand as show of force to Russia. Trips to Georgia should go along.

Like it or not – The Bosporus has become a bargaining chip. NATO should make contingency plans how to close the Bosporus for Russian warships, should Russia invade Eastern Ukraine or Moldova. NATO must make clear to Russia that a price to pay for further annexation of territories would the loss of access through the Bosporus.France, Please Cancel the Mistral Deal

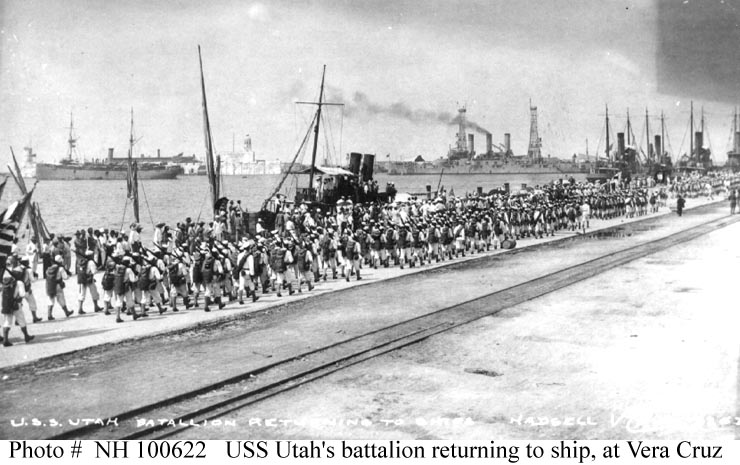

|

| French Mistral LHD. (Source: Wikipedia Commons) |

Russia could have done military campaigns like Georgia 2008 or Crimea 2014 much easier with one of the Mistrals. One of these LHD would also be useful for Russia’s navy in campaigns against Moldova, with regard to Gagauzia and Transnistria, or even against Estonia, because the Mistrals can serve as a platform for command and control, attack helicopters and landing troops.

That Russia announced to base its Mistrals in the Pacific does not mean that they will operate there. For its Syria show-of-force, Russia deployed warships from its Pacific Fleet to the Med’.

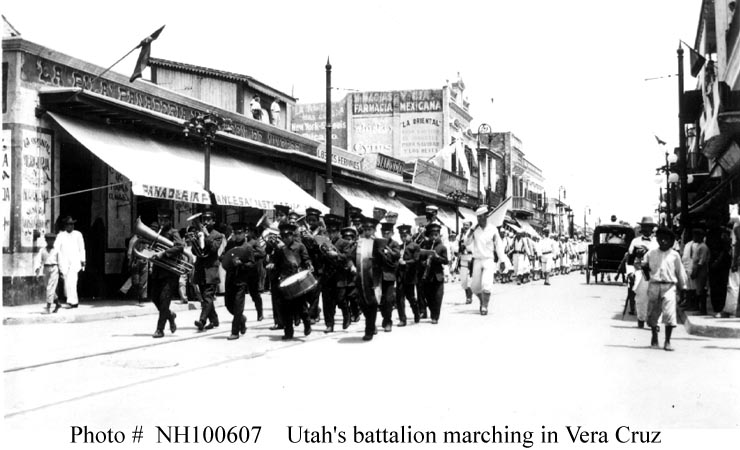

|

| Baltic Sea (Source: Wikipedia Commons) |

With the entry of the Baltic Countries and Poland into NATO and EU, the Baltic Sea was a solely political issue, not worth military considerations. This has changed, too. However, this does not mean that we are on the brink of war. Nevertheless, NATO needs to make plans how to deter Russia from threatening the Baltic Countries from the sea. The Alliance must make sure that its naval superiority in Baltic remains clear. Deploying an SNMCMG to the Baltic and regular naval exercises, such as BALTOPS (non-NATO), are efforts worth doing. Moreover, Sweden and Finland should join NATO. Both countries would bring great contributions to NATO and their membership would even increase Russia’s isolation in the Baltic Sea.

|

| Ohio-Class SSBN, US Navy (Source: Wikipedia Commons) |

No matter about the massive unpopularity – Europe will need the nuclear umbrella provided by the US, UK and France. We are not yet back in the pre-1989 times. There is not yet a Cold War 2.0 at sea. However, if we forget the lessons learned of nuclear and conventional deterrence, we may find ourselves in exactly these situations much sooner than we think.

NATO-Building Starts at Home

NATO’s pivot to Russia will shift attention away from the maritime domain back to the continent. Armies and air forces will receive, once again, much more attention than navies. While Putin’s aggression increased the importance of NATO for its member states, maritime security’s relevance for member states and, therefore, for the Alliance will decrease. In consequence, theaters like the Persian Gulf and the Indian Ocean will become of much less concern for NATO.

In case the Crimea Crisis did not happen, NATO, to sustain its relevance, would probably have looked for new maritime tasks in the Med’, Gulf of Guinea and the Indian Ocean, maybe even in Southeast Asia. However, thanks to Putin, we will find NATO’s warships deployed back in the Baltic and the Black Sea. Given Operation Ocean Shield ends this year, we will not see NATO back in the Indian Ocean very soon; except maybe for a few friendly port visits. After Crimea and with Putin’s hands on Eastern Ukraine and Moldova, NATO’s debates about partners across the globe and global alliance are finally dead.

Felix Seidler is a fellow at the Institute for Security Policy, University of Kiel, Germany, and runs the site Seidlers-Sicherheitspolitik.net (Seidler’s Security Policy).

Follow Felix on Twitter: @SeidersSiPo